Roy Moller - Interview

by John Clarkson

published: 6 / 8 / 2019

intro

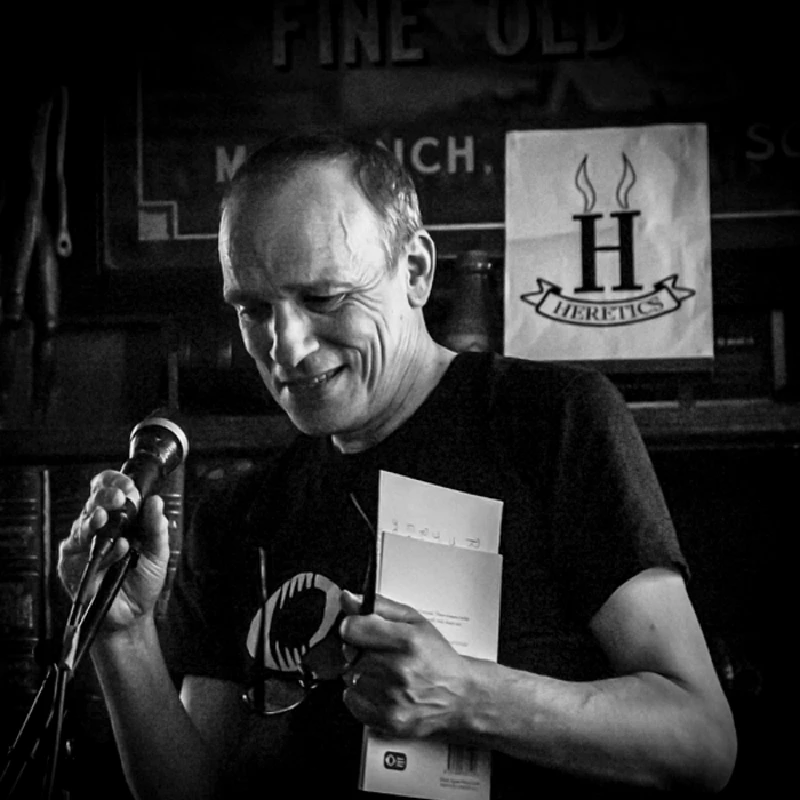

Scottish singer-songwriter and poet Roy Moller talks to John Clarkson about his new poetry collection 'Be My Baby', which was inspired by the story of his adoption and which saw his birth mother travel from Toronto to Edinburgh to give birth to him.

In May 2015, Roy Moller went to Register House in Edinburgh to have his adoption papers opened. The Scottish singer-songwriter and poet, who was born in 1963, had been adopted as a baby, but had never learned whom his real parents were. What he found out was remarkable. Carol Hoffman, his birth mother, had been a reporter on ‘The Toronto Telegram’ in Canada. When she had accidentally fallen pregnant, knowing the backlash that she would face for this in her then starchly conservative home country in which unmarried mothers were treated as fallen women, she had travelled to Edinburgh, where she had given birth to her baby, before handing him over for adoption and returning home. It took more searching by Moller to confirm that he had been the product of an extra-marital affair and that his father was Jim Kennedy, a photographer on ‘The Toronto Telegram’ and a World War II veteran. Kennedy, who died in 2001, already had children, and Carol, who passed away in 2014, after returning to Toronto, eventually married and also had a family. Moller, who was brought up an only child in North Edinburgh, discovered that he has between his father and mother’s families six half siblings and a step-brother and sister, and has been over to Canada to meet them. Roy Moller, who lives now in the town of Dunbar thirty miles outside Edinburgh, has released six albums, ‘Speak When I’m Spoken To’ (Book Club Records, 2007), ‘Playing Songs No One’s Listening To’ (The Beautiful Music, 2011), ‘The Singing’s Getting Better’ (recorded with Sporting Hero and released on the Mecca Holding Co., 2012), ‘One Domino’ (Stereogram Recordings, 2014), ‘My Week’s Better Than Your Year’ (Stereogram Recordings, 2014) and ‘There’s a Thousand Untold Stories’ (The Beautiful Music, 2016). He has also published a previous book of poetry, ‘Imports’ (Appletree Writers’ Press, 2015). His second collection of poetry will be published by the Edinburgh publishing company Dionysia Press in September. It was originally going to be called ‘Carol’ before Moller changed its title to ‘Be My Baby’, partially in tribute to the Ronettes’ hit which was recorded in the same week that he was born. Reflecting on the tale of his adoption, it is divided into four parts. In the first and longest part, also titled ‘Be My Baby’, which runs across the opening half of the book, he imagines his mother’s life as a newspaper journalist in Toronto, her arrival in Edinburgh, his birth in Simpson’s Maternity hospital under his original name of James Hoffman and his adoption by Peter and Mollie Moller, a youth club leader and teacher. It concludes with his christening in St Giles’ Cathedral in mid-1964 under his new name, and Carol’s own eventual wedding to another newspaperman when he was seven. The second part, ‘Tides’, reflects on his first trip to Toronto on a family holiday as a sixteen-year old in 1979 before he knew of his connection there, his discovery at “fifty-odd” of who his father and mother were, and Jim Kennedy’s experiences in Occupied Europe when he was the only member of his troop to survive after a personnel carrier they were travelling on was blown up on a bridge. In the third part ‘Settler’s Song’ he recalls his upbringing with his adoptive parents, and in the fourth part ‘Hindsight’ he weighs up and considers the circumstances which led to him being adopted and brought up in a different country from Carol and Jim. Pennyblackmusic spoke to Roy Moller about ‘Be My Baby’ and discovering who he is. PB: ‘Imports’, your previous collection of poetry, told loosely of your upbringing in Edinburgh, and your return to the East coast of Scotland after many years spent living in Glasgow. You wrote over half the poems for that collection before you had a formal structure or theme for it. ‘Be My Baby’ has much more of a direct focus. How easy or difficult was it getting into that focus? RM: It was easier because I knew that the poems would all deal with a particular subject matter. It was, however, difficult trying to get the sequence correct, especially as when I was writing it I started finding more about my father’s side of the family. I had to decide then whether to concentrate on my mother’s story first and then to go on to tell about my father, or to interweave the two stories chronologically. I ended up dealing with things in the way that I found out about them because I found out about my father quite a while after I found out about my mother. I had gone over to Canada and met my family on my mother’s side before I had any proof of who my father actually was. PB: How easy was it for you getting that proof of who your father was? RM: What happened was that I went up to Register House in Edinburgh and had my adoption records opened. They were literally in a sealed envelope which had not been opened since 1964. There were details in there such as my mother’s middle name, and I also found out her address in Toronto from the terms of my adoption, and so I was immediately able to take things further. Within 24 hours of that, I was emailing somebody who I thought was probably her stepson and, therefore, my stepbrother, Guy Crittenden, and that turned out to be the case. He got back in touch with me very quickly, and he sent me a lot of information and also a lot of photographs of my mother, and said, “We think that you father might have been someone who worked with her at ‘The Toronto Telegram’. We think that it might have been a photographer whose name was Jim. So, that was the first nugget of information that I had really and a pretty good clue, but I had no absolute proof other than what was an unsubstantiated rumour. It took a lot of searching before I eventually found out more information through a family tree on an ancestry website. It mentioned a photographer on ‘The Toronto Telegram’ who was called Jim Kennedy, and from there on in everything fell into place. PB: How long did it take you after finding out who your mother was to find out who your father was? RM: It was probably about eighteen months. Even in this day and age with the Internet and the resources that we have, finding out proof of things that took place long ago in the past is difficult. My mother kept things very, very quiet, and there were really only a few whispers to go on. When you are tracing your own family tree quite a lot of guess work can go into it, but when it is a relation as close as your own father you don’t really want to start approaching people and intruding on their lives if they aren’t actually the people you thought they were. You have to try and be sensitive to that. You don’t want to go in first and say this is definitely the person before you have any proof. PB: It wasn’t uncommon for girls in the early 1960s who had had babies out of wedlock to be forced to give them up. They were different times, weren’t they? RM: In Toronto it was much more difficult than it was over here in Scotland. The way unmarried mothers were treated was quite severe. The society over there was very Presbyterian. We were more broadminded as a state at that point. We had the Welfare State with the NHS, and the taboos in Canada were stronger. It was in 1963 that things started to change. Popular culture as we know it started then. I was born on the 3nd July, and two days before that the Beatles recorded ‘She Loves You’, and two days after that the Ronettes recorded ‘Be My Baby’. So, I was born bang in the centre of that. I tried to bring a little bit of that into the book. PB: The book was originally going to be called ‘Carol’ after your mother, wasn’t it? RM: It was. Then a film came out called ‘Carol’, and then I found out about my father and his story and his father’s story, and things broadened out. I decided to go with ‘Be My Baby’ instead. PB: At the beginning of ‘Be My Baby’ and in what is the title poem you get into an imaginary conversation with the film director Martin Scorsese. You then speak to him again in the last lines of the final poem, ‘Hindsight’. His film ‘Mean Streets’ has the Ronettes’ ‘Be My Baby’ on the opening credits of its soundtrack. Is that a homage to that? RM: That’s right. I was trying to evoke that but not to over play it (Laughs). I was born at this pop culture moment, and I thought, “What is the best way to set the scene here?” and I felt, “Okay, there are certain parallels with ‘Mean Streets’”. The evocative sound of the pop music of the time is something that I love and which I am familiar with. I am a Ronettes fan. I am a Beatles fan, and I really wanted to put the fact that these two important records came out the week I was born into the backdrop of ‘Be My Baby’. I had various drafts in which I went in wider to the Scorsese side of things and I thought, “Maybe I could work in the famous tracking shot from ‘GoodFellas’”, but I thought, “No, just bring it in here and bring it in there, but don’t over play your hand because then you will get away from your own story.” The main idea behind ‘Be My Baby’ as a title, however, was the fact that my mother decided at one level to keep me. I don’t know what option she really had, but in ‘Selkie Baby’, one of the poems I say “She has chosen to have me…have me to give me away.” She didn’t have the pregnancy terminated. She wanted to have the baby, and then having had the baby she had to cover her tracks because she went back to Canada in a very short time after having me. In fact, she signed me off too early. In one of the papers I found amongst my adoption papers, she had to send approval of my adoption for a second time, so she was obviously in quite a hurry. PB: How long was she actually in the UK for? RM: I don’t know. There are whole parts of the story which are still a mystery, and I hope that is one of the things which comes through in the course of the book is that I am not an all seeing narrator. There are things which I don’t know. I don’t even know for certain if she flew to the UK. She may have sailed. The earliest date I have for her is April 1963 when she went to the adoption agency, and the last record that I have for her is mid-July 1963 when a couple of weeks after I was adopted she signed me off. PB: The reader comes away from these poems admiring her and thinking what a brave lady. With all these odds stacked against her, she did the right thing by you. RM: Yes, exactly. I know from speaking to her family that it would have been in her nature to secure for me the very best and she didn’t want to just offload me. She wanted to make sure that I was well catered for. She showed a lot of fortitude. She was 28 when she had me. She was obviously mature in years, but it took an awful lot of bravery to do that. I am glad that that comes through. The last lines in the book and of the poem ‘Hindsight’ are “I ask you, Mr Scorsese, what is ‘Be My Baby’ if not a song of love?” So, the book is a love song to her. PB: You show absolutely no anger towards her at all in the book. You are in fact very philosophical about things, saying in ‘Hindsight’ “time was not ready”. RM: No, time was not ready. I wish that I could have met her and my father before they passed. What happened happened and what didn’t happen happened, but I am of such an age now that if I can’t be philosophical in my 50s when can I be (Laughs)? The fact that I was conceived outside marriage is not something that I feel I can really take a moral position on. I love them both and I wouldn’t be here without either of them. PB: When did you find out that you were adopted? RM: I always knew. ‘Mum ‘and ‘Dad’ are my adopted parents in the book, and ‘Father ‘and ‘Mother’ are my blood parents. My mum Mollie used to tell me almost as a sort of lullaby thing , “We picked you out. We chose you.” I think that this is something that adopted parents say a lot to their children - “Other parents have to take what they are given but we chose you.” She told me that she and my dad had come to the ward and picked me out because I was smiling at them, and it was only when I had my adoption records opened that I found the real version of what had really happened. I use it in ‘Mollie’s Lullaby’’, one of the poems in the book. My mum and dad used a private adoption agency, and they passed the test for prospective adoptive parents, and they made a pitch looking for me. They were looking for a child to turn up from the year before I was born, so I don’t think I was chosen from lying in the cot. That was the story that I, however, grew up with. PB: You describe in ‘Be My Baby’ how you first went to find out who you were at Register House in Edinburgh as a teenager but were sent away as you were too young. Why did you leave it so late and until you were in your early 50s before going back there again? RM: It wasn’t too long after I went to Register House that my dad died suddenly in 1982. It was partially because of that and then my mum became more elderly, so it didn’t seem quite the right thing to do. It wouldn’t have been unsupported in retrospect, I guess, but at the time it just didn’t feel the right thing to do. I also didn’t know that it was now possible to have your adoption records opened, and it wasn’t until I spoke to a friend of mine, David Paul, who was interested in genealogy and he said, “Oh, you need to go up and get them opened,” that I found out that you could do that. I had no idea that that was possible until then. If I had looked into it with more focus I would have known, but I just put it into the back of my mind. When my mum died in 2009 and I had my own infant son Peter, that piqued my own interest again. I was 44 when he was born, and that was the first time that I had looked at another face and known he was related to me. Without wanting to be sentimental about it, it was the greatest moment of my life when he was born, and when I was holding him for the first time I realised, “Wow! This is a human being that is related to me. This is a first.” That was a pretty powerful motivation for finding out more. I knew where he came from on his mother’s side, but I didn’t know where he came from on my side. I wanted to do that for me and him. I wanted to give him some back story because I had been born without any back story that I was aware of. He had only got one side, and I wanted to furnish him with both sides. For me, it means so much to me to have made contact with my kin on the Hoffman and Kennedy sides. PB: Your father seemed to have lived quite a colourful life. He had been almost killed in the war, and his father had wound up in Canada after being sent to reform school. RM: I don’t really go into it in the book but his father didn’t really completely reform , shall we say?) My father grew up in an unsettled home, and the family went through quite a lot of poverty. One of his brothers turned out to have a knack for business, and went from having a hard start to being a millionaire race horse owner. My father worked as a carny for a while, and then went into the Forces in World War II. He was in the Forces for almost five years, and was almost blown up on a bridge and was the only one in his troop to survive, before ending up as a photo-journalist for the paper. If he hadn’t fallen into the river when the bridge was blown up and the river hadn’t broken his fall, he wouldn’t have survived that incident. Everything is based on chance and fate, but that was quite a stark example of it. Of course, if his father hadn’t gone to reform school he wouldn’t have been sent to Canada and met my grandmother. It is true of everyone, but it really is quite graphically the case how big a chance has played in the whole story. PB: Last couple of questions. How long did it take you to write ‘Be My Baby’? RM: I would say nigh on four years. It took a long time but it went through many, many drafts and it is something which I might add to when I find out more things if there is ever a future edition or a sequel. I see it as an ongoing thing, but I think there is enough there at the moment to make it a book. PB: You have not released an album since 2016 and that album, ‘There's A Thousand Untold Stories’, consisted largely of material which was already a couple of years old. Is your music career on permanent or temporary hold? RM: While I was writing ‘Be My Baby’, there was no real desire on my part to write music. It was such a focus, but almost immediately after I turned the manuscript in I had an informal song-writing session with my friend Gary Thom, who I had written songs with before. We got a couple of songs out of that, and since then I have been on a bit of a roll with it and I have got about fifteen or sixteen new songs. I had got to a point in which I had probably written enough songs to play that nobody had ever heard, but having this manuscript out of the way it just seemed, “Oh, I used to do this,” and it is a pleasure. I am still writing poetry, but it seemed the right time to start doing it again. We have got the backing tracks done of a track ‘Semicolon’ done and just got the vocals to do, and that will be coming out on Stereogram hopefully in August. PB: Thank you. The main photo is from Offbeat Pictures and the lower photo is by Ryan McGoverne Photography.

Band Links:-

https://www.facebook.com/RoyMoller1963https://roymoller.bandcamp.com/

Have a Listen:-

Picture Gallery:-

interviews |

|

Interview (2023) |

|

| Edinburgh-born singer and songwriter Roy Moller speaks to John Clarkson about his new album ‘Be My Baby’,which is about his discovery that his birth parents were Canadian and that his mother flew from Toronto to Edinburgh to give birth to and put him up for adoption. |

| Interview (2022) |

| Interview (2015) |

| Interview (2012) |

features |

|

Competition (2016) |

|

| We have five copies of Scottish singer-songwriter's 'There's a Thousand Untold Stories' (with 'There's a Thousand More Untold Stories' to give away as competition prizes.) |

reviews |

|

Songs From Be My Baby (2023) |

|

| Challenging but highly rewarding autobiographical album from Scottish singer-songwriter Roy Moller in which he reflects upon his upbringing as an adopted child |

| There is a Thousand Untold Stories (2016) |

| Another Man's God (2015) |

| One Domino (2014) |

| Playing Songs No One's Listening To (2011) |

| Speak When I'm Spoken To (2007) |

| Fermez La Bouche (2005) |

| Second City Firsts (2005) |

| Maximum Smile (2003) |

most viewed articles

current edition

Carl Ewens - David Bowie 1964 to 1982 On Track: Every Album, Every SongArmory Show - Interview with Richard Jobson

John McKay - Interview

Colin Blunstone - Thalia Hall, Chicago, 16/7/2025

Billie Eilish - O2 Arena, London, 10/7/2025

Bathers - Photoscapes 1

Visor Fest - Valencia, Spain, 26/9/2025...27/9/2025

Loft - Interview

Sir Tim Rice - Interview

Robert Forster - Interview

previous editions

Manic Street Preachers - (Gig of a Lifetime) Millennium Stadium, Cardiff, December 1999Heavenly - P.U.N.K. Girl EP

Beautiful South - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

Peter Perrett - In Dreams Begin Responsibilities Interview Part One

Boomtown Rats - Ten Songs That Made Me Love....

Oasis - Oasis, Earl's Court, London, 1995

Trudie Myerscough-Harris - Interview

Coldplay - Wembley Arena. London, 16/8/2022

Prolapse - Interview

Pixies - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

most viewed reviews

current edition

Davey Woodward - Mumbo in the JumboSick Man of Europe - The Sick Man of Europe

Lucy Spraggan - Other Sides of the Moon

Suzanne Vega - Flying With Angels

Amy Macdonald - Is This What You've Been Waiting For?

Phew, Erika Kobayashi,, Dieter Moebius - Radium Girls

Bush - I Beat Loneliness

Blueboy - 2

Alice Cooper - The Revenge of Alice Cooper

Cynthia Erivo - I Forgive You

related articles |

|

Band of Holy Joy/Cathode Ray: Feature (2016 |

|

| Pennyblackmusic presents three acts from the Edinburgh-based label – The Band of Holy Joy, The Cathode Ray and Roy Moller – at the Sebright Arms on April 15th |

Pennyblackmusic Regular Contributors

Adrian Janes

Amanda J. Window

Andrew Twambley

Anthony Dhanendran

Benjamin Howarth

Cila Warncke

Daniel Cressey

Darren Aston

Dastardly

Dave Goodwin

Denzil Watson

Dominic B. Simpson

Eoghan Lyng

Fiona Hutchings

Harry Sherriff

Helen Tipping

Jamie Rowland

John Clarkson

Julie Cruickshank

Kimberly Bright

Lisa Torem

Maarten Schiethart