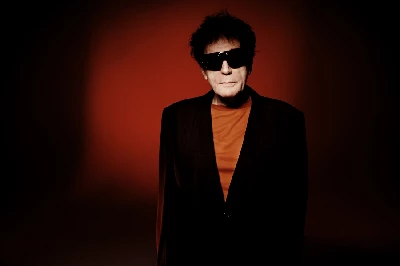

Peter Perrett - In Dreams Begin Responsibilities Interview Part Two

by Steve Miles

published: 19 / 12 / 2024

‘I wanna die in the same place I was born/ Miles from nowhere’ – Peter Perrett, Part Two. We ended the first half of this two-part interview with Peter Perrett on the release of ‘The Cleansing,’ with the legendary singer songwriter discussing the importance of the album’s sequencing in telling a story and taking the listener on a journey. In part two we continue in the same vein, looking back over the journey of his life and work, and taking in his observations about Johnny Marr, Bob Dylan, his family and The Spanish Civil War, amongst other topics, along the way. NB The following continues from topics and threads explored in Part One, which ought to be read before starting on this second half. As we saw at the end of the first part of this interview, there’s a hint in the last song on Peter Perrett’s new album that death brings clarity – although there’s also the strong suggestion that it brings nothing at all. If there is clarity, this may be through ‘terminal lucidity’ - see below - or it may be through the sense that when something ends that creates order; the finalising of a story. Some people, who know they’re dying, take the opportunity to ‘get their affairs in order.’ Wanting to be in control of the end of the story of life is what’s behind the album’s song, ‘Do Not Resuscitate,’ explored above, and both Peter and his son, Jamie, have spoken about this album as if it might be his last, which has given the project a gravitas that pop music mostly lacks. I drove home from work in early 1997 to find a handwritten note in the flat from my wife, only recently declared pregnant for the first time, to ring her as soon as I got in. This was the old pre-mobile days, of course. I rang her and she was at my Mum’s house. She said, ‘You’d better come over. It’s your Dad.’ I said, ‘Is he dead?’ – I’ll never know why; maybe from the tone of her voice – and she said he was. He’d gone to the pub at lunchtime, as normal, then come home feeling a tightness in his chest. After lunch it was still there, so he went round to the doctors’ surgery – these were the days when you could do that – and they told him he had indigestion and gave him a prescription for some stomach medicine. On the way to the chemist, he died of a massive heart attack. It rankles to this day that the doctor was never held to account for that. Rankles badly. But at the time it wasn’t the uppermost concern we had, so he got away with it. It didn’t come as a surprise that Dad was dead, not really, although the actual event was entirely unexpected. He smoked at least 60 cigarettes a day and drank every lunchtime and some evenings. He liked tripe. He never exercised. His own father had died before he was sixty himself and he was always so anxious that he’d never get to enjoy life after work, that when he did manage early retirement, aged 60, he was as happy as I ever saw him. The ten years he unexpectedly had left were his happiest in my lifetime, and the best in our relationship together. But he never wanted to discuss death, and when he left us that day, there was no sense of an ending being natural, or bringing closure. That was 27 years ago – getting on for half my life - and yet I’ve recently recorded a song for the forthcoming European Sun album about him, which just goes to show how I’m still coming to terms with his loss now. He never got to see a grandchild, barely saw me have a proper job, and certainly never saw me behave as a grown up in any way. Gwen had been conceived, and we’d recently told him about her, but I’d ruined all his joy by telling him there was no way I’d be bringing a baby into a smoke-riddled house, so if he wanted to see her, he’d have to quit or come to us. Therein lies the stuff of ineradicable regret. Despite ostensibly being much more healthy than Dad, I was equally desperate to take early retirement, mostly because I have always much preferred not working to working, but also because there’s so much I still want to do. So when the chance to turn redundancy into early retirement was offered last year, I was overjoyed - thrilled by the same sense of relief as Dad – and felt unbound when the day finally came. A couple of months after retirement started, however, I became oddly overwhelmed by the completely unexpected fear that the time left wouldn’t be enough to do all that I wanted to do. It has taken me most of the subsequent year to get over that, exacerbated as it was by some minor health scares – a bad knee, a ‘pre-diabetic’ warning by text, and a breathing test that came back saying my lungs were those of an average 78 year old - and my naturally glass-half-empty disposition. Howard Devoto’s words about, ‘Putting myself through hell, waiting for hell to begin,’ (Magazine – ‘Sweetheart Contract’) never fitted so well, even though I’ve been trying to learn from them since 1980, and fear now I never will, try as I might. But I’m over it now, I think, as much as I’ll ever be. The last six months have been as good as any I can remember and feel like I’m hitting my after-work stride, though even just writing that seems like tempting fate, because death can strike at any moment, and the older you get the more you become aware of that fact. People died when I was young, of course. A tragic plane crash took the parents of some of my primary school friends and a row of lonely-looking poplar trees still marks the memory in my local recreation ground; car accidents prematurely claimed the lives of a couple of people I knew in their teens and early twenties and some old relatives I couldn’t remember ever having met had funerals - but death seemed very much the exception rather than the rule. The older you get, the less that’s the case. I think the main source of the anxiety that swamped that first winter of my retirement was probably the premature death of a friend of mine the previous summer. I’d first come across Chris Amaworo-Wilson at work about ten years previously. He was the only person I knew who had even seen my all-time guitar hero, Robert Quine, in real life, let alone met him. Once I discovered he’d rehearsed with him too, he shot onto a personal pedestal that he never really fell off. I don't know what made me think that someone whose hands had glided across the fretboard while standing between Robert Quine and Lloyd Cole, who’d been bandmates with members of The Psychedelic Furs, toured across the US and Europe in his own band, and been on Conan and Top of the Pops, would play with me – me, a man still regularly looking at the strings mid-song to see where to put his fingers and always forgetting the words... But I asked him anyway, and he did, because he was a generous man, and he genuinely liked my songs. After that first gig in August 2015 with drums, The Short Stories became just me and Chris, playing acoustically, but we never recorded anything properly, and when I did get those songs on record it was with other friends, as European Sun. Happy as I am with that, I do wish I had more to show for my time with Chris, not just because he was the most talented musician I ever met, but also because he was possibly the nicest too. He didn't need to rehearse, which was frustrating and wonderful in equal measure, and although he always managed to look the very definition of cool, he didn't need to hear applause. He'd arrive almost too late to soundcheck, and slope off unnoticed straight after we came offstage, while people around me raved about 'that great bassist with the other bloke'. We didn’t even do many gigs, as first our respective young twins got in the way, then the chance to create European Sun, then Covid, and finally his cancer. Instead, we just met every so often and talked. Talked about my next album, which he wanted to play keyboards on; talked about our respective kids and the blessings and burdens of fatherhood. Towards the end, we talked about his poetry - the thousand poems that flowed after his diagnosis and which captured, with erudition, wit and skill, the incredible range of experiences he had crammed into his life. I never once heard him complain about his cancer, although he may have to others. He didn't rail to me against the ridiculous injustice of the pointless, random, spiteful bloody disease picking on him of all people; he didn’t moan about the far-too-soon-ness of it all, even though he was younger than me, or dwell on the debilitating, shrinking limitations it placed on him. Nor, in the main, did he even let the tragedy of it for all those who loved him overcome his spirits. At least, not when we met. Even in dying, he showed himself a better man than me. All the above perhaps goes to shows that I’m well-placed to understand the sense of foreboding and finality in Peter’s recent life and work. Going back to ‘The Cleansing,’ Peter shares that, ‘I recorded ‘Solitary Confinement’ on an acoustic specifically to give Johnny Marr a blank canvas, because he was the last guest to get involved. Jamie said, ‘You've got Carlos, you've got Bobby, why not ask Johnny? We always talked about collaborating, but because he lives in Manchester, it’s not so easy, whereas Carlos and Bobby live around the corner to me - the collaboration was just, you know, walking up the road and coming back! But by the time I sent him stuff, he said, oh, you know, there's tons of great guitar on it already. ‘World in Chains’ was one song that had some space and he brought a great guitar that went really well with Jamie's, but I thought it'd be good to give him that. ‘Solitary Confinement’ was the last song I wrote for the album, after it was nearly completed, and I sent it to him, just the vocals and acoustic guitar, and he put three guitars on it and sent it back within about three, four hours. It's very professional, the way he does stuff. It’s no surprise to hear that the song was written last, as it adds lovely little deep, additional colours to the themes developed across the songs, almost like a footnote to the album, picking out the similarities between love and art – ‘Dreams that can be shared/ Mean more than life itself’ – augmenting the nihilistic agnosticism of the album’s reflections on fate – ‘That rescue party's never coming/ That wait is gonna be in vain’ – and maybe even remorse for the ‘wasted years’ of drug use: ‘You been doing time in solitary confinement’. The mid-album song ‘Set The House On Fire’ is about Xena, but with the same unflinching candour laced in that we have seen in other songs. Utilising fire at first as a familiar metaphor for passion – ‘When we met she lit a flame/ I had never felt that way’ – Peter goes on to reflect on the remarkable eventualities of his notoriously drug-drenched decades. The innocent bystander may well think that ‘My little girl cooking up a storm… She would set the house on fire’ is simply about passion but there’s also a more prosaic and less inspirational origin: ‘Yeah, Xena used to have accidents with fire, you know, because of the drugs we took. The line between consciousness and unconsciousness would sometimes be crossed while she was over the stove, and her head would nod down towards the hot plate, and luckily her hair was long so that would catch fire first and wake her up before her face actually hit the hot plate. Quite often I'd hear the kitchen tiles exploding. It's an eventful life that we led even, though it was very boring. The routine was the same but crazy stuff happened along the way.’ It's a crazy story, but it makes me smile. I’ve never taken any drugs at all, but I have also had memorable accidents with cooking. I was renting a bungalow a couple of years after my first wife and I separated, and my older daughters remember that I used to wear a cheap, blue dressing gown all the time which was clearly made of a highly flammable material. The cooker in this place was gas, which was new to me, and so there was a naked flame underneath the frying pan whenever I made pancakes. Time and again, they’d hear me shouting from the kitchen that I was on fire again, and come in to see the sleeve flaming away, acrid smoke filling the room. The middle of the kitchen was an island of cardboard boxes that I’d never unpacked, so I had to dance around that to get to the sink or the door to put the flame out. You may find it hard to believe that it happened more than once, but it did indeed happen many, many times. I’ve never been one of those people who says, ‘I never make the same mistake twice.’ Like a good scientist, I make them multiple times, just to make sure that the results hold true. And that doesn’t just go for setting fire to dressing gowns, that goes for romance, work, friendship, and pretty much everything. The album’s key songs have more sides to them than some of the simpler tracks, and you will have to listen to them for yourselves because I have long since believed that all album/book/gig/film/play reviews etc should be forbidden by law from being published until at least six months after the release/event. Capitalism’s voracious marketplace couldn’t live with that, of course, but how, seriously, can anyone judge something properly after one watch/ two listens/ one sleep after the event? It’s ludicrous. I’ve broken my own rule here, but only because I have the artist himself to give most of the content. The heart of the album is, I’m afraid, unfairly ignored in this piece, because the best songs need more time than I have at my disposal now to be done justice to. The album’s title track, ‘The Cleansing’, is certainly one I need to listen to more before I say anything much about it. It’s about Peter himself, clearly, and he notes that it’s, ‘Personal, but also relating to the universal. Reflecting on life's journey. Probably discovering that it means less than nothing. And that's the way I feel about me, and I feel it about the tragic demise of this civilization.’ The phrase ‘dead survivor’, which Peter explains as meaning, ‘Sometimes it seems that you can only survive, if the previous incumbent is dead,’ clearly has a lot more resonance than that in the whole context of the album. The same is true of the key track, ‘Art Is A Disease,’ which he explains as, ‘A sort of hymn for the struggling artist, which is anybody that stands naked, exhibiting their innermost feelings. It’s a vulnerable place. And it can be quite a challenging place to be, especially for people that receive no acclaim. Both my children are struggling artists. Jamie writes his own songs and records them, and I see so many artists that have got talent that just never get any recognition at all. And I think those are the sort of artists I identify with, because I feel like an outsider. I don't feel like part of the music business, but I’m happy to be an outsider looking in because I think that's a much more advantageous viewpoint from an artist's point of view. It’s too easy to get sucked into being a performer. I retired when I was 28 years old, and I'm lucky that I've got a hobby that I can use as therapy. And I'm lucky that there are still people alive that saw me in my youth, when I had the energy to jump about the stage. But there are lots of people, talented people, that never, ever get in their one second in the spotlight. And I know the pain that they can feel. And it is an addiction. If it's inside you, you just can't stop doing it, unless you nullify your feelings. Which is the way I avoided it. It became a self-fulfilling prophecy.’ This, of course, ties in with ‘Back in The Hole,’ the album’s central track about depression, as both songs explore the entire album’s key themes in crucial ways. But that’s another one I need to hear a lot more before I delve into deep analysis… Peter complains throughout the interview that his memory isn’t what it was. ‘From the age of 60, I noticed my memory going. I think it's an ageing process where your brain shrinks and stuff like that. And I'm not able to access words in conversation in real time the same way that I can when I can sit down and take my time to think. So, yeah, I find that I can express myself better through some lyrics.’ But it doesn’t seem that way to me. Whereas I often struggle to recall what day of the week it is at any given time, he cites the day, month and year of many of his recollections and leaves me with the sense he could reveal hours and minutes if pushed. He remembers all the lyrics he’s ever written, including some not yet released, but jokes darkly that this an end-of-life perk: ‘Xena mentioned this. As we've been getting older, she comes out with things that surprise me like this idea of terminal lucidity: there's no way to prove it, but apparently people that have suffered from dementia at the last minute can recognize people. I thought it was nice to think that you could get an extended period of terminal lucidity.’ The phrase plays a key role in the title track, ‘Lost at sea/ Following your dreams/ Dedication to the cause/ Comes with the territory/ Sophistry, fiendish alchemy/ All that's left to aim for - Terminal Lucidity' We saw above how he also remembered, and corrected, a few small mistakes in my original piece, displaying a remarkably precise grasp of his own narrative and oeuvre. But, like I said, his memory seems fine to me, as he proves when telling me how another song came to fruition. ‘Certain things I can remember, like ‘Kill A Franco Spy’, I can remember every single thing about that. It was summer 2021, there's a knock on the door and it's Bobby Gillespie with Warren Ellis. I hadn’t seen Warren for about four years, and he said, ‘How are you doing, Peter?’ And I said, ‘I feel like I’m on my last legs’ - you know, after not being out of the house for 18 months or whatever. Anyway, they stayed a couple of hours and when they left, I just wrote down the single line, ‘I’ve been trying to crawl towards you on my last legs’ which I thought was quite a good line - sometimes I’ll write down a line or a couplet that I think resonates in some way and I could use later. Then later that day I happened to watch ‘The Lady From Shanghai’, the Orson Wells film, which I hadn't seen probably for close on fifty years. It's not one of his best films (he's got the worst Irish accent) but because he's a genius, even his worst work has got moments of genius in it - the scene in the aquarium is amazing, it’s incredible just as visual art. So, early on, he came out with that line about another character – ‘He could kill a spy with his bare hands’ - and he was speaking in admiration for this this person, and that's what resonated, because obviously I’m politically left. So I remembered that line, but then at the very end of the film, in the last scene, Rita Hayworth has been shot and she's actually crawling on her knees towards Orson Wells and that immediately clicked, that the vision of her crawling to him, with what I’d written earlier. And the last dialogue of the film was her saying, ‘Give my love to the sunrise,’ and I thought that was such an incredible thing – for your last dying breath, you say ‘Give my love to the sunrise.’ And so I fitted them all together. Then I added ‘Amnesty amnesia/ Pretend it makes it easier,’ which is a reference to the Spanish Amnesty Law of 1977. Franco died in ‘75 and after they passed the Spanish Amnesty Law. On the surface you think amnesty is a good word, you associate it with Amnesty International - amnesty is generally a good thing - but it's a paradox, a contradiction, because while was a tiny bit of good that came out of it in that they released a lot of socialists that were still in prison, so they got their freedom, the greater evil was that all the murderers and torturers were pardoned and it meant there was no closure for the relatives of the people whose loved ones had disappeared or tortured. They didn't know where their remains were. There was no closure for them. Amnesty and amnesia are related words [from Greek amnestia "forgetfulness] and it's good to say, ‘Oh let's be friends and go forward into the future, let's not be chained and burdened by the past,’ but it leaves so much unresolved: sometimes things are buried in the past that you can't relinquish. You can't free yourself from the: so, though most people assume amnesty is a good thing, it can be used in in nefarious ways. So, with that song, there were tiny steps throughout the day towards the completed song and so I can remember the whole process.’ We circle back to the album’s elegiac tone. ‘Well, I'm 72! How old are you? You sound very fucking young. You've got a young voice. How old are you? You've got a very young voice. You sound alive. You know, if it was like the last thing I ever did, it'd be a fitting end. It feels like a body of work that makes statements about different aspects of life from an idiosyncratic perspective. I think I've got a voice which is identifiable. It's unique. I think that's the most important thing a singer can have, and I don't think anybody's lived a life with the same experiences as me - people have gone part of the way but there's a depth to my experiences – even though I always advise anybody that there is a downside to drugs, you can't change the past. So I accept my choices. I was very impulsive when I was young, but I'm aware of the word ‘consequences’ now. And I literally haven't got the energy to be angry or impulsive, so I take my time. I'm much more considered: I look both ways before crossing the road! I think my brain is still there. I mean, I’ve started not quite remembering things that I expect to be able to remember, but, yeah, 72 is quite an achievement, and you can't help thinking ‘Don't take tomorrow for granted’. I've recorded vocals and rhythm guitar for more songs already, but whether I'm around to see them completed, who knows? You know what I mean? I could surprise myself and be here when I'm 90. I mean, it seemed unlikely that I'd be here when I was 72! I ask him, Do you look back and think, I wish I'd done, I'd made more records or, or do you look back and think, you know, or are you at peace with the life you've had? ‘Well, I'm at peace with where I am now. Although it sounds like regret, when I say ‘Just another wasted life, just another dead survivor,’ it's, like, so what? I'm just one of many people that this happens to. And how can you complain? There's lots of people in Gaza at the moment that would love to live my life. I'm really happy. Now as an artist, do I wish I'd done 30 albums, all of the same standard of The Cleansing and other stuff that I've been proud of? That would be great. But there are so many artists that - I think you touched on it in your original piece - that have done some great stuff, but have done so much mediocre stuff too, where they're just doing it by numbers. For anybody coming new to their body of work, it's hard to see the wood for the trees. You know, who knows what it's like to be Bob Dylan? He's living his dream, and the people prepared to worship at the altar. Like I said before, I don't know whether I'd be in such a happy place now if I'd have carried on through those intervening years. I like to think that I'm very special. And I like to think that if I'd have done albums throughout the ages, that they would all have been special because when I pick up a guitar, I will write some chords and then I'll write a song. So I'd like to think that if I'd have done more work, it would have been of a standard, but would I have maintained my enthusiasm for doing it in that, all that time? So I'm quite happy. The fact that I haven't been a prolific artist, I think has helped me focus on the small, tiny bits of treasure that I've been able to accumulate in my active years. I've got stuff that could come out posthumously, like ‘Remains’ did after The Only Ones. Um, uh, yeah. When the Only Ones reformed, we actually did go into the studio but when we got back together, the rest of the band were in good shape and I was in terrible shape. I was still using drugs, my voice was fucked because I’d realized that I had COPD and what they prescribe you is inhalers. You do four of them a day and I was taking a hundred of them a day, thinking it's going to help me breathe better - not realising that steroid inhalers actually damage your voice box. But yeah, there will be a posthumous album of songs that are outtakes from, from my recent work. And I was going to call it End Trails, you know, after Remains, cause Remains was what was left after The Only Ones. End Trails. With the letters in different sizes, so the D is really small.’ And it's nice to think that your thoughts are taken seriously. Because, like, quite often you do interviews with people, and it's just a job, and they like your music. But like I said, I'm touched and humbled that you take my words as seriously as I do. Because, obviously, to write them in the first place, writing them is therapy for me.’ When I had nearly finished this piece, I asked Peter if he’d like to read it before it was published. That’s a hard question to ask, because I don’t think a writer should get the subject’s approval of what they write, but he did share some things that I promised not to make public, and so I wanted to honour that trust in me. He replied, ‘I dunno. I usually don’t like reading about myself, or hearing my speaking voice. Maybe I should check for any factual inaccuracies?’ Which reminded me of how, when I was about ten maybe, I was taken with a couple of mates to a television studio by my friend’s dad, who worked there, to see it out of interest, I suppose. When we were there, he recorded us talking to each other in a big microphone. These were the days before normal people had any means of recording themselves in their homes, so I’d never heard my voice except through my own ears before. It was back when photos were expensive, precious things you had to send off to get developed, and which always came back disappointingly indistinct and curiously both exciting and dissatisfying. Back when there was only one mirror in the house, steaming up above the bathroom sink. Back when, in short, self-image was a gloriously inaccessible concept, and the idea of a selfie was reserved for museum oil paintings of the rich and famous. It was also the days when I played my records on the one piece of ‘hi-fi’ we had in the house, my Mum and Dad’s living room record player unit, which meant I could hardly discern the subtleties of recording, and often misheard lyrics, there being no internet to look them up on. I had been horrified when I heard my own voice for the first time as a boy. It sounded nothing like I thought it did, and I refused to believe at first that it was really me. Inexplicably, it dented my self-confidence permanently, and acts as a metaphor and an emotional turning point for all my later-life’s damaging shyness. Even in my early thirties, when a Men’s Group I had briefly joined to try to find a safe space to explore my masculinity, had a session where we all went into a field to shout as loud as we could, I simply couldn’t. Even in an empty field, with safe acquaintances, I couldn’t raise my voice. They all bellowed and yelled into the grassy void, barely troubling the cows in the distance, nervous but thrilled to have touched their ‘primal scream’, while I drove home, tail between my legs, belittled and let down by myself yet again. If you ever accidentally hear the Short Stories’ lo-fi debut album, you’ll hear me speaking all my lyrics, not able to even try to sing them, or having my bandmate Tim sing them for me. It wasn’t until I was 46, on the second album, that I finally had a go, having sort of sung live the year before, and even then, I quite dishonourably hoodwinked some adult students into doing a part of one song (Sorry!), and persuaded Martin Bramah, of the Blue Orchids (Thanks!), to kindly do another. I tell you all this because it explains why, from the age of fifteen, for at least 25 years after, I fully believed that the line, ‘Ever since I heard the way you talk/I wanted you,’ on The Only Ones’ ‘Language Problem,’ was, in fact, ‘Ever since I heard the way I talk/What a joke.’ That’s what I heard, that’s what I sung along to, and that’s the shared feeling I falsely credited Peter with expressing on my behalf. Does that prove that we hear what we choose to believe? Perhaps. But it couldn’t happen today, because I have better headphones and genius.com to correct me. What do you believe in, I ask Peter? ‘Well, obviously, I believe in in my wife. She's been the one constant throughout my adult life. I met her when I was 16, and in January, we've been together for 56 years, so through every trial and tribulation, every hardship, it's been the one thing that's kept me afloat. She’s kept my head above water. Without her support I might have drowned. Just the truth and honesty - that's the one thing that I’ve given her. You know, she can't trust my behaviour because it can be aberrant and unpredictable, but she can trust my love - Oh God, you're like a fucking therapist because you get me onto subjects which I want to talk to you about, but I wouldn't want to be made public…’ Later I ask him about his children. Jamie and Peter Jr both play on the record and is his live band, and he’s often said that he wouldn’t be back in music without them. But stories of his ‘lost’ years suggest that it must not have been easy for them growing up I ask him, and yet they survived, and give him so much. ‘Well, they didn't survive, you know. All the time, Jamie says I should be paying for his therapy now… They’re good human beings. I like to consider myself a good human being and Xena definitely is, but they've certainly suffered from that lifestyle. There’s a litany of events that would traumatize any child. Peter doesn’t dwell on things that happened; he approaches things with a sort of a resigned acceptance. They remember things from a different perspective and sometimes we can laugh at it, but it's definitely a gallows tragedy within the comedy. I mean, it's not fun having police around and having junkies with needles hanging out of their arms, sitting on their bed, not letting them get to sleep… We went through great times where we could control everything, but we went through chaotic times as well, where we didn't actually control anything, and I just think that I’m extremely fortunate that through all that, they still respect me care about me and love me, because I don't deserve it. I treated my own parents with total disrespect. I didn't have any time for them at all. In the ‘Sixties it was like a war, a generational divide. People rebelled against everything their parents stood for, and I treated them like the enemy. But it had to be people that are as close to me as my kids to actually bring me out of retirement because getting clean was one thing, but then thinking about actually performing live again… That's something they just coaxed me back into. And once I started doing it, I started enjoying it, and then it was a gradual process. But if we didn't play music together, we'd probably not have an excuse to see each other. At the time we consoled ourselves saying, ‘Well, we really love our kids,’ but we didn't really demonstrate that love in any traditional meaningful way, so I’m very fortunate to have the love of my children. In ‘Back In The Hole,’ there’s a line, ‘We follow our parents into the flames,’ which is obviously the flames of when you’re cremated: you throw your parents into the flames. We all try to be good parents, but in the end you've got to shoulder the blame for all the things that your kids struggle with. You can't help but blame yourself for inadequate parenting. You know, when people say their partner is pregnant, I always offer my condolences. You can't be selfish anymore, because there's someone that theoretically is more important than you that has got to be taken into consideration, and should come first, and that is quite an imposition on somebody who likes to think of themselves as a totally free, with no restrictions or restraints.’ I’ve never felt free, ever. So whilst I recognise how much responsibility and constraint comes with having children, I don’t resent it as much as he does. I don’t, however, disagree with Peter’s recognition that there’s no suffering like the feeling you have when your child is suffering, or that the anxiety you feel for them is far greater than the anxiety you feel for yourself. Every thwarted hope my children have brings pangs of failure to me; why didn’t I protect them? Every harmful, or merely less than perfect, trait they display causes me to chastise myself with my own parental shortcomings; I should have set them on a better path. Every bad choice they make, and every disappointment they suffer, causes me pain: why didn’t I guide them more positively? Of course, I do the same to myself about my own disappointments and regrets – or, as Peter sings, ‘Nothing ventured, nothing lost.’ But there’s no getting away from the fact that the older you are, the more past you have, and therefore the more it seems inevitable that your mind will drift there. The longer you’re a parent, the more you think about parenthood. The more people you know die, the more you think about death. I’ve written about this recently already, constantly surprised, as I am, by the amount of looking into the past my contemporaries and those older than us seem to do. But one of the reasons why I don’t share Peter Perrett’s emotional response to having children is precisely because they have a bigger future than me. The fact that my little ones are only just ten gave me real cause to worry about not reaching a decent old age, for their sakes. But with two primary age children in the house, and two smart, interested, and interesting, young adults forming the rest of my four daughters, I’m constantly kept on my toes, never able to rest on my laurels and constantly stretched to look forward, not back. That’s one of the best gifts they have given me. I once bought a t-shirt that said, ‘I’ve got two daughters, you can’t scare me’. Then I had two more girls, which I hadn’t expected, and so I got a permanent marker to cross out the ‘two’ and write in ‘four’. I wore it a lot. The t-shirt’s just a gardening shirt now, but the sentiment remains. After all, ‘To plant a garden,’ as Audrey Hepburn apparently said, ‘is to believe in tomorrow,’ which is why I’m as likely to be digging as writing, and more likely to be planting than singing. Albeit all with headphones on always with music in my ears… and often, that’s the voice of Peter Perrett. Which brings us back to the ending of ‘The Lady From Shanghai’: ‘Elsa: It's true. I made a lot of mistakes. Michael: You said the world's bad. We can't run away from the badness. And you're right there. But you said we can't fight it. We must deal with the badness, make terms. And then the badness'll deal with you, and make its own terms, in the end, surely. Elsa: You can fight, but what good is it? Goodbye. Michael: You mean we can't win? Elsa: No, we can't win. Give my love to the sunrise. Michael: We can't lose, either. Only if we quit. Elsa: And you're not going to. Michael: Not again! Elsa: Oh Michael, I'm afraid. [He walks away] Elsa: Michael, come back here. Michael! Please! I don't want to die! I don’t want to die!’

Also In In Dreams Begins Responsibilities

In Dreams Begin Responsibilities (2024)

In Dreams Begin Responsibilities (2023)

In Dreams Begin Responsibilities (2023)

In Dreams Begin Responsibilities (2023)

Article Links:-

https://peterperrett.com/https://www.facebook.com/peterperrettmusic

https://www.instagram.com/peterperrett/

https://x.com/thepeterperrett

Play in YouTube:-

Picture Gallery:-

intro

In part two of his interview with Peter Perrett, Stee Miles continus to look back with him over the journey of his life and work, and takes in his observations about Johnny Marr, Bob Dylan, his family and The Spanish Civil War.

features |

|

In Dreams Begin Responsibilities Interview Part One (2024) |

|

| In the first of a special, in-depth two-part interview, Steve Miles talks with legendary singer songwriter Peter Perrett about his new album, ‘The Cleansing,’ his life, his career, and why he doesn’t want to be resuscitated. |

most viewed articles

current edition

Shrag - Huw Stephens Session 08.12.10 and Marc Riley Session 21.03.12Gary Numan - Berserker

Razorlight - Photoscapes

John Hassall - Photoscapes

Max Bianco and the BlueHearts - Troubadour, London, 29/3/2025

Primal Scream - Photoscapes

Roberta Flack - 1937 - 2025

Waeve - Club Academy, Manchester, 18/3/2025

previous editions

Heavenly - P.U.N.K. Girl EPManic Street Preachers - (Gig of a Lifetime) Millennium Stadium, Cardiff, December 1999

Boomtown Rats - Ten Songs That Made Me Love....

Beautiful South - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

Barrie Barlow - Interview

Oasis - Oasis, Earl's Court, London, 1995

Trudie Myerscough-Harris - Interview

Dwina Gibb - Interview

Pixies - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

Doris Brendel - Interview

most viewed reviews

Pennyblackmusic Regular Contributors

Adrian Janes

Amanda J. Window

Andrew Twambley

Anthony Dhanendran

Benjamin Howarth

Cila Warncke

Daniel Cressey

Darren Aston

Dastardly

Dave Goodwin

Denzil Watson

Dominic B. Simpson

Eoghan Lyng

Fiona Hutchings

Harry Sherriff

Helen Tipping

Jamie Rowland

John Clarkson

Julie Cruickshank

Kimberly Bright

Lisa Torem

Maarten Schiethart