In Dreams Begin Responsibilities - #16: Living in the Minds of Strangers

by Steve Miles

published: 29 / 10 / 2024

intro

Steve Miles discusses the newly-published biography of Josef K and writes about the struggles of the urge to be creative.

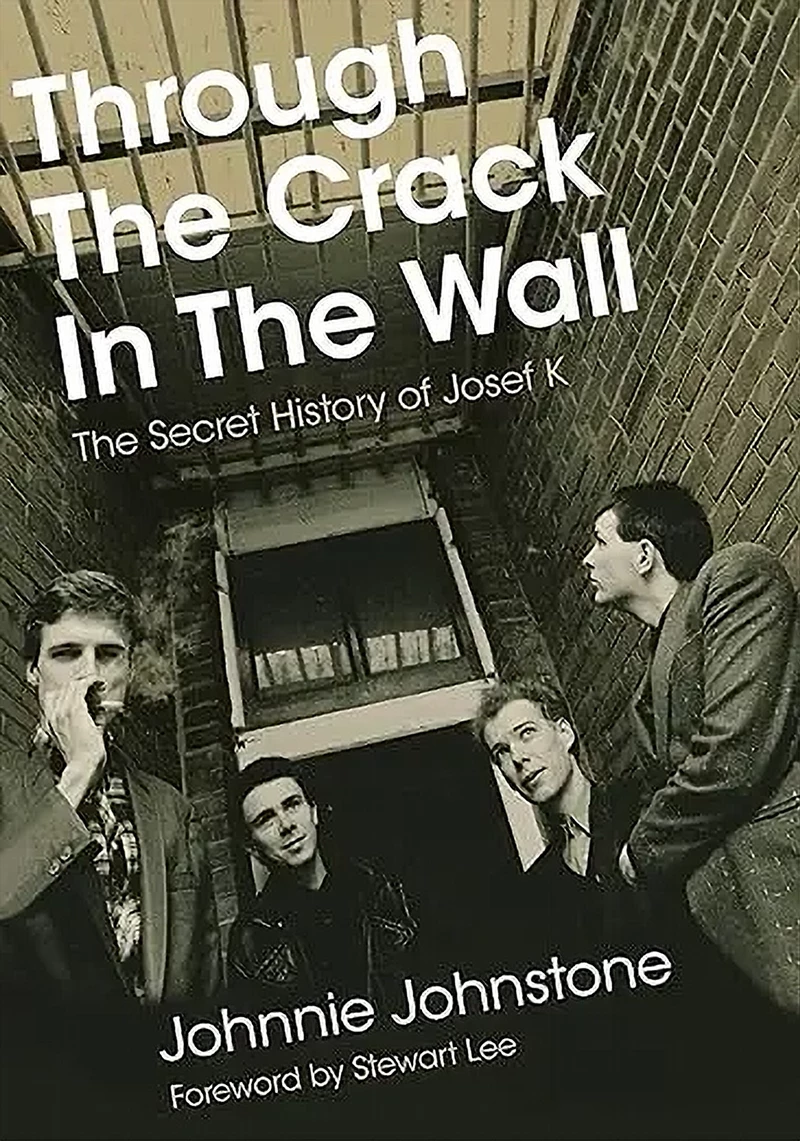

‘I don’t dislike rock stars. I just don’t want to be one’- Paul Haig, 1981 (quoted in ‘Through The Crack In The Wall: The Secret History of Josef K’ by Johnnie Johnstone). ‘This tremendous world I have in my head. But how to free myself and free it without being torn to pieces. And a thousand times rather be torn to pieces than retain it in me or bury it. That, indeed, is why I am here, that is quite clear to me.’ – Franz Kafka, Diaries, 21st June 1913. Like many a young man obsessed with music, I fantasised about having my own band as a teenager. I went so far as to invent a stage name for myself/name for the band. I tried to draw it out as a logo. I didn’t show anyone. It was all in my own mind. Josef K were, by contrast, a real band. I heard their singles, bought their solitary album, and saw them play, albeit just once. So I knew they were real. Their band got into the minds of strangers. In their time, Josef K were a difficult band to be a fan of, even if you liked them. It wasn't clear when or where the next record was coming from: the album that was promised never arrived, and then suddenly a different one did, which the journalists who had adored them incomprehensibly slated. You wondered why live, on record and on John Peel, they sounded like three different combos, and why they released their most fully realised song to date in a perfect mix only once they’d split up. Johnnie Johnstone has unpicked all this in his just-published biography of Josef K. I really enjoyed the book because it did the three things which a good rock book should do: Firstly, it reminded me of why I love the band (or if it's a band you didn't know, tells you why you should love them). Secondly, it made me listen again, perhaps more carefully than ever, to their recorded output. And thirdly, it filled in a few of the gaps in my knowledge of the band, because they weren’t all that well-known at the time, when a few, heavy-pressed, scratchy Postcard-label seven-inches were pretty much all there was to go on. Meanwhile, I was much too shy to even fantasise about the fame and fortune/ being-on-stage aspects of being in a band, too reticent indeed to so much as whisper a word of my inventions to a soul. It wasn’t so much that I wanted to create music per se, and I certainly didn’t want to be a star. The bit I wanted was to have my voice heard: not - heaven forbid! – my literal voice, but, you know, to be understood, or listened to. To have my ideas and emotions validated, I suppose. And I had this idea to do that required getting into the minds of strangers. But I wouldn’t do that if it meant actually performing, or making music, it transpired. Learning an instrument looked like hard work. I had a strong sense that I had no natural aptitude and no-one I knew could play anything, so there were no family or friends to align with. We had no money for instruments or lessons. As for singing, I wouldn’t even ever join in in assembly with the hymns, I’d just open my mouth and mime for a bit when a teacher fixed me with a glare. In something like a funeral or a wedding, where people standing next to you would know if you were silent, I’d just mumble and hum enough to pretend I was making an effort. (Besides, God was invariably involved, and it seemed hypocritical to say His name if I didn’t believe in him, so even when I mumbled I always made sure not to say ‘God’ or ‘Lord’ or ‘Jesus’ when it came to it in the hymn.) That was my way of pretending I was being true to myself without standing out. Just like wearing fluorescent socks to school, which I did, not simply, as I would tell myself, because that was the only item of clothing not specified in the uniform code, but more significantly, because my rebellion went unnoticed. It didn’t mark me out from the crowd, except to myself. I wrote poems, of course, because I was a sensitive teenage boy, but the only poets I knew were the ones we did in school. Dead ones in tatty old schoolbooks. I liked some of them a lot, but they didn’t have drums and no-one at school painted the logos of poets on their school bags and there wasn’t a poetry section in the NME. I know that because the first of my two attempts to be published during my school years was when I sent a political protest poem to their editor. They didn’t print it. (The second attempt was a review of a gig by The Fall. They didn’t print that either.) But I had read ‘The Trial’ by Franz Kafka, and so I immediately recognised the band Josef K (named after the novel’s protagonist) as being fellow-travellers down the less-travelled roads of alienation and angst even before I’d ever heard what they sounded like. Theirs is an interesting story, as it highlights both the pros and cons of being in a band – not the groupies, addiction and early death kind of cons, but the soft politics, interpersonal relationships parts of it. The what-happens-when-your-dreams-go-out-into-the-world part of it, and it’s not a highly publicised story so I was thrilled when I heard that someone had written a book about it. It’s not a highly publicised story because Josef K aren’t highly publicised, and it might not mean too much if you don’t actually like the band’s music. But luckily I do: indeed, as I have said before, they have the rare quality of seeming better now than when I first heard them. Johnnie Johnstone makes a valiant effort of seeking out the few celebrities who have acknowledged their quality or influence, and the members of Josef K, in turn, acknowledge their influences: ‘ ‘For Paul and me, the main thing was definitely the Velvets. That was how we started, doing Velvet Underground covers, so they were immediately the biggest influence. Their music seemed so important. In fact, I loved the whole New York scene that followed on from that. We both did. Television and Talking Heads were huge influences as well. I liked Robert Quine and some other guitarists as well, but I particularly loved Tom Verlaine’s angular style, which was always so interesting rhythmically. Then it had that discordance as well.’ There was still another group with whom Malcolm had recently become obsessed. ‘If I’m being honest, at the time I met Paul I probably just wanted to make music like Pere Ubu. They were a really big influence for me, and of course Subway Sect, who just seemed more intelligent than the other bands. But it was definitely the East Coast American art-punk scene that attracted us the most, and we really kind of saw it as an extension of The Velvet Underground.’ The parallels between Ross’s skidding chalk-on-chalkboard guitar— like metal lacerating glass—and Tom Herman’s scorching guitar lines on the early Pere Ubu records are straightforward enough to detect.’ So far, so utterly ‘me, too’. But even though the members of Josef K had the jump on me by a) learning instruments b) meeting each other c) rehearsing, and d) telling people they were a band, I still had one other thing, apart from our influences, in common with them – a band name. Johnstone describes the importance perfectly: ‘Often, a band’s name is the first thing agreed upon. An important decision. Even before they’ve written a line or played a note, they may have already imagined their name on a bill poster or a record sleeve or splashed across the NME’s front cover. Sometimes, the choice of name is a statement of intent, a manifesto for the future. Possibly, it might contain a more subtle or discrete reference to seduce those of a similar disposition, or it might cultivate an appropriate air of mystique.’ At this point, I should point out, Josef K were actually called TV Art, which is kind of the same thing as Josef K but way less clever, and their songs were equally prototype vehicles, though when their album-length demo of TV Art songs was finally released some thirty years after they broke up, I was more than pleasantly surprised by the quality of it, and I would cherish it even if Josef K had never existed. I was particularly bemused for a while by the centrality of keyboard sounds on the TV Art recordings, because Josef K were such a quintessentially guitar-based band, until I realised that one of the things that made Josef K special was the way parts that might be played on a keyboard accompanying a guitar were played on second guitar in Josef K’s recordings. Johnstone’s book, perhaps disappointingly, doesn’t go into much depth or detail about the actual arrangements and recordings, but the reader can always go the songs and listen for themselves (just don’t look for their lyrics online; it’s almost criminal how wrongly transcribed they are, and I know this even though I can’t be sure what they are myself). As Johnstone remarks, ‘Scattered throughout the [TV Art] tape are seeds that anticipate the thrilling urgency characteristic of the band in full flight. Ronnie’s percussion on ‘Final Request’ is terrific, effortlessly mixing up the tempo alongside Malcolm’s falling-backward-down-the-stairs guitar.’ Of course, Josef K were also inspired by punk. It’s hard to overstate how much effect punk had on the people it had an effect on. Even people like Johnstone, who was too young to have experienced it himself. He quotes Josef K’s Malcolm Ross: ‘I would never have made music had it not been for punk. I was never going to be in a prog rock band or play blues guitar. There were a lot of people who would never have made music if punk hadn’t happened. A lot of the best pop music is not made by great musicians. Punk changed everything for us. But we were never punk.’ Punk and post-punk had a sense of being a movement, a fellowship, that in turn made making music seem so less daunting for those who felt the urge: suddenly, it wasn’t strangers’ minds you were trying to get into, but just friends you hadn’t met yet. Bands quickly found their fans; fans quickly found their bands. This is a big part of Paul Hanley’s enjoyable recent book about the Buzzcocks too: he quotes Pete Shelley as saying, ‘The important thing about punk was that it was an idea… It made people active participants in the culture rather than passive consumers – it networked people together.’ Johnnie Johnstone recounts the story of Steven Daly of Orange Juice travelling far from home to see a favoured band: ‘I went on the afternoon of the gig to look around the record shops, then went up to the venue to listen in to the soundcheck... I met this guy hanging around outside. We got talking. He told me he was in a group too, and we decided to stay in touch. The guy was Malcolm Ross.’ That was the serendipity that punk made possible. I, of course, was much too shy to approach anyone else at the gigs I attended, except for the bands themselves who I always tried to cross-examine if I got the chance. But Josef K, though clearly far more socially adept than me, had their own inbuilt limitations which were, ultimately, to prove the band’s undoing. ‘We didn’t like talking to promoters as much as possible from the music business. We just thought that they weren’t in the gang or on the same wavelength. I suppose we were quite puritanical. And we didn’t like sexism or laddishness’ – Malcolm Ross. The crux of Johnstone’s book is probably this exploration of how the fit for Josef K between their dreams and those new friends was never quite right – how the journalists, record companies and other business acquaintances didn’t quite see things as they did, and never quite smoothed their path the way they should have. But I’m getting ahead of myself. Josef K are already recording their demo and I’m still sitting on the bus doodling imaginary band logos. Despite my strong sense of kinship with all the bands mentioned so far, and those surrounding Josef K as they came to make records, I didn’t believe there was an audience waiting for me. And yet I wanted that audience. Why was that, I wonder? Why do we feel that in order to be fully realised as human beings, we need to make an impression in the minds of people we don’t know? Was it because I didn’t get the validation I craved from those people who did know me in daily life? Or was it because that’s the model we’re sold? That those people who really matter are those who leave something behind outside of their immediate circle? You don’t get a Blue Plaque for living quietly in your street, but only for doing something in it that people who DON’T live in your road hear about. Making your own garden beautiful, or your own house clean and warm, nurturing your family, caring for an aged parent, reading a lot of books – none of these things get a Plaque. Being kind to everyone you meet doesn’t get you a Gold Record or a Bafta or the Booker Prize. It’s getting into the minds of strangers that seems to count if you want to be thought worthwhile. And so some people dedicate their lives to that very thing. But it’s not so easy, is it? It takes effort. It takes luck. And it takes talent – or it did in the days before social media, before talent was replaced by money, family and looks. But even if you start to have success it’s not easy - because, by definition, as you intrude into the lives of strangers you expand the area of your life over which you have no control, as Josef K very clearly found to their cost. None of that stopped me, however, from conspiring in secret with myself to make my move on the minds of strangers, or even eventually attempting to inflict some homegrown ‘music’ from my imaginary band on my school friends. At home we had acquired a large, square, plastic cassette recorder which came with a large, square, plastic microphone, and my mother had begun to learn to play a nylon-stringed acoustic guitar in night school. I scraped the tape player’s microphone up and down the strings to create a kind of pseudo-electric discordant noise and recorded it. One lunchtime, the sixth form stereo was duly hijacked, and my musical debut was made. It may only have lasted seconds – that’s likely. But I don't recall any reaction. I don’t think that was the point - the doing was the important bit because for a second I was at least attempting to reach the minds of strangers. By then, I knew several people who were in bands or knew people in bands, but that still never seemed even a remote possibility for me. It was like they were French people, say, and I was born in England, so I knew I’d never be French. I had several years earlier once shared with my best friend a lyric I thought could kick start our collaboration - not that he had any aptitude or the slightest desire to be in a band himself – but he had scoffed at the line, ‘First you kiss me then you kill me’, and I was somewhat hurt that my best effort to channel my inner Howard Devoto fell on deaf ears. It took years to recover. ‘We’re all so weak, so frail it’s unfair’ – ‘It’s Kinda Funny’, Josef K. After that my own musical ambitions remained a pipe dream – if making no effort to make your dreams come true can still count as a pipe dream… I did slowly learn a few basic chords on my mum's nylon guitar, and in my mid-twenties purchased an electric guitar, second-hand from somewhere disreputable. No amplifier, just the guitar on which I could practise quietly. And I wrote several actual ‘songs’, all of which I imposed on my then girlfriend. She was kindly supportive but unable to summon any great enthusiasm. I had lots and lots of thoughts and feelings in these years, and I believed that they were clever and interesting. But I was also, for whatever reason, pretty certain that strangers’ minds were not willing to accommodate my thoughts and feelings entering them, and also inexplicably sure that I was incapable of dealing with what might happen if I did. Torn between the internal imperative to create and the emotional imperative to keep quiet, I carried on strumming an unplugged guitar and filling up notebooks with my confused insights, postponing my fame until some future date when either I, or the world, might have drastically changed. By then, by contrast, Josef K had made a few singles, played some gigs, gone to Belgium, recorded an album, scrapped it, recorded it again, released it, fallen out with the music press, broken up, and slowly faded from the picture, never really to return. (The few bits and pieces they did individually afterwards never spoke to me, and after a while, I stopped looking out for them.) Meanwhile, short of cash one month, I sold that cheap black Les Paul copy and became once again as far from being in a band as it is possible to be. My musical career lived completely in my mind once more, and not even the echo of it reached the minds of strangers. ‘Singing this song I’m eternally grateful/ Saying these words I’m eternally grateful’ – ‘The Missionary’, Josef K. Some people are happy just reading books and listening to music, watching films and looking at paintings. Others feel the burning need to join in, to reflect back that passion by adding some of their own to the mix. Sometimes it’s really specific, trying to almost ‘be’ the star you like - to write like Keats or to look like Marc Bolan. It’s a form of play, but often, that’s the starting point for a career. Johnstone quotes Paul Haig as saying, ‘When I first heard Talking Heads 77 and Marquee Moon, I thought, were I to craft a sound, it would be based on those records, but of course your own sound becomes more a mish-mash of various influences.’ Every creative act is the same; it begins with imitation. If you’re successful, over time, what you do becomes authentic. Josef K were a great example of this and Johnstone is really good on this aspect of the band’s genesis, whether it be the bands lyrics: ‘ ‘I was reading an awful lot,’ Haig later told Grant McPhee. ‘Kafka, Albert Camus, Knut Hamsun. There was this recurring theme of alienation that ran through all of their books, and that had a big effect on my lyrics.’ Or whether it be the band’s music: ‘Ross started off with a Rickenbacker but soon after elected to play a Fender Jazzmaster in imitation of Verlaine. Paul, meanwhile, started off with a Columbus Gibson copy, the guitar Lou Reed brandishes on the cover of Transformer, but soon ‘upgraded’ to a Fender Mustang’. They ended up recording ‘The Missionary’, the ‘farewell’ single, released in 1982; a song that captures the very essence of the band, channelling but transcending all their influences - a song that only Josef K could ever have composed or played. One of the joys of a book like this or Paul Hanley’s is that there’s a delight to be prompted, as a like-minded reader, to recall your own similar journeys of discovery. The journeys in the mind, with the books and bands you explored and grew up with, and grew through, and the physical journeys that sometimes also involved – travels from your front door in the pursuit of spiritual nourishment. Johnstone tells us that, ‘Naturally, Josef K were in awe of Joy Division—so much so that Malcolm even traded in the wonky keyboard he used on ‘Chance Meeting’ and the early demos to buy bus tickets for himself and Paul to go and see the band play at the ULU in February 1980. The pair ended up spending an uncomfortable night wandering about London in the middle of the night before roughing it at Victoria Station until the earliest bus to Edinburgh turned up.’ Hanley talks of all the same things in the Buzzcocks book: that it was the mention of The Stooges in a review of the Sex Pistols that made them sit up and take notice: ‘Because as far as we knew, nobody else knew about The Stooges. It was like finding someone who spoke our language’ – Pete Shelley, quoted in ‘Sixteen Again’. And that review alone was enough to inspire them to make the journey one weekend from Manchester to London to see the as yet unsigned band, and the rest is history. Later Hanley tells of his own trip to buy Buzzcocks’ second album, ‘Love Bites,’ the day it came out in loving, personal detail, emphasising the emotional and tangible resonance of music in his own personal development. Two cultural visits of my own to London in my university days came back to me as I read these two books. One, which I took by myself, involved miles of almost-lost walking and some anxious clambering over locked gates, to Highgate cemetery to find the statue of Karl Marx. I wrote pencil notes, in awe, in the margins of my dog-eared A-Z, under his imposing stone head, noting the cobwebs in his eyes, and felt that I had somehow achieved some sort of significant spiritual moment, like a minor pilgrimage. The other, an even more legendary occasion in my own mind, was a trip to the Rock Garden to see The Blue Orchids at their peak, an event recorded for posterity on possibly that same large, square, plastic tape recorder in distorted lo-fi quality. It remained marked in my memory, beyond the excellence of the event, thanks to my decision to stay for the encore. That meant missing the last connection and spending the whole night huddled up against a cold red brick wall in Didcot station waiting for the morning trains to start again. I knew what I was doing, I should add, when I decided to stay for two more songs; I knew I was choosing eight hours of a train station bench instead of my bed. That’s what music meant to me. And it was reassuring and warming to read that Ross and Haig did the same for Joy Division. ‘You lived in the past dear/ With things we all gave up then.’ - ‘Chance Meeting,’ Josef K. Johnnie Johnston’s book is one of many similar efforts that have bubbled up in recent years. It sometimes seems that those folk of a certain age who haven’t written a book about their time in a band are in the minority, and where the band members haven’t written them, a fan has. I could easily spend all my life reading these books because they are guaranteed to tap into comfortable memories, reaffirm my prejudices and beliefs, and satisfy my curiosity. Many are very poorly written, however, and many have little to say, so I tread carefully, though not always without error. In any case, it’s vital not to get stuck in the past as you get older. This book, however, is one that rewards the reader, for the time spent on it. Mainly this is because the author’s love for the subject is what guides everything. He’s only written the book because he loves the band and wants to do justice to them. By definition, therefore, it’s a book about the author too, probably almost as much as it is a book about the band. Paul Hanley’s excellent recent Buzzcocks book, ‘Sixteen Again’, is similar, although his memories of the band are more direct than Johnstone’s are. But both books are about the authors as much as the bands they love. In fact, Hanley’s book is even subtitled, ‘How Pete Shelley & Buzzcocks Changed Manchester Music (and me)’. Understandably, these kinds of memoirs and biographies usually attempt to place their subjects in their cultural and socio-political context, but since the authors are mostly record buyers, not sociologists or historians, it usually means (for punk and post punk readers) hearing over and again the same recycled generalisations about the dole, art school culture, ‘overblown’ prog rock precursors, Thatcher, racism, and the power of the NME. Johnstone, whilst not avoiding that altogether, does so with a deft touch which is more subtle than many other recent efforts. He’s better – and this is a lesson for other would-be biographers - on the material that is specific to the band – the Edinburgh of the time, for example, is vividly recreated, with apt choice of details: ‘Edinburgh Castle is built on an extinct volcano that elevates it above the city’s theatrical landscape of gothic spires and steeples, charcoaled cobblestoned streets, and winding alleyways that slope down from craggy green hills to the port at Leith.’ At the age of about 30, I think, I suddenly decided that my dream had always been to be a drummer. I say ‘suddenly’ but it had always been drums that attracted me more than anything else to songs at first hearing. The first album I ever bought for myself was acquired purely on the strength of the extended drum roll that started the band’s first single, and I have a sneaky suspicion that for all the good reasons I loved the Buzzcocks, the intense emotional connection between my soul and John Maher’s effortless fills might be right there at the top. ‘Those golden moments/ Have vanished forever’ – ‘Final Request’, Josef K. Paul Hanley’s book focuses on these same kinds of feelings, even more than Johnnie Johnstone’s. Both books are a long, posthumous fan-letter to the artist, embroidered with research, targeted at the minds of strangers, and both evoked the same kind of nostalgia and pleasure. The key difference for me was that I knew just about everything in Paul Hanley’s book already, whereas much of Johnstone’s book was new to me. ‘If a man has his eyes bound, you can encourage him as much as you like to stare through the bandage, but he'll never see anything.’ – Franz Kafka, ‘The Castle’. Somewhat inexplicably, I looked in the small ads in the paper and bought the first drum kit I saw. I was incredibly lucky with the kit that I got. It was beautiful. A Pearl kit all in silver with new Paiste cymbals. A thing of beauty. I struggled to put it together back home and was immediately confronted by the very reasons I had never had one before. First, I didn't know how to play drums, and secondly, I had nowhere to play them, living as I did in a rented flat above an Off Licence. I attempted to rectify the first by driving to a part of town inhabited by far more outgoing and bohemian people than I knew, to take a drum lesson. The teacher seemed a bit taken aback by my efforts, saying he couldn't believe that I had never played drums before. I was flattered but also slightly cowed by this confrontation and never returned for a second time. The emotions of that first lesson were just like a first gig. There was me, displaying my musical prowess, laying bare my musical dreams, and receiving the askant reaction of a stranger. It put me off doing it again any time soon. Johnnie Johnstone’s account of Josef K’s first gig wasn’t perhaps dissimilar: ‘The occasion, a party for a friend of Malcolm’s brother Gavin, meant it was a typically low-key first show containing its fair share of false starts, bum notes, furrowed brows, and indignant exchanges, as the band tried to negotiate shaky covers of ‘Psycho Killer’, ‘Prove It’, ‘Be My Wife’, ‘What In The World’, ‘Sweet Jane’, and ‘I’m Waiting For The Man’. In a way, it had felt like going to the dentist.’ Determining to teach myself the drums, I soon found that I could keep a beat quite well, but that mastering those basics seemed to be the limit of my potential. Besides, it was really boring after the first ten minutes of adrenalin wore off, hitting things by yourself in secret. The deeply authentic lesson that being in a band means a lot of travelling, waiting, setting things up, repeating what you’ve done before, and then doing all the same in reverse (all of which probably drove the Buzzcocks off the cliff, according to Hanley’s carefully-researched depiction of events), however, was lost on me, and I decided that I could learn to play better in a band. "The right perception of any matter and the misunderstanding of the same matter do not wholly exclude each other." – Franz Kafka, ‘The Trial’. An advert for a local band looking for a drummer who successfully played weddings and dances and the like was swiftly answered. An excruciatingly embarrassing evening followed, where my lack of knowledge of even the simplest standard techniques used in popular music was gruesomely revealed. Even that I might have got around with time, if they’d liked me enough, but what really killed it was when they asked me to play song after song from the ‘classic rock songbook’ and I had never heard of any of them and told them so: Clapton? Eagles? Fleetwood Mac? No, sorry. These were the kind of songs which every covers band of the time had in their repertoire, but which as a punk, I loathed by reputation enough to have avoided ever hearing. Not knowing any popular songs, or how to play along with other instruments, was, it transpired, an insuperable obstacle to joining a well-paid, well-meaning bunch of semi-professional musicians who weren’t inspired by Spiral Scratch. Strangers’ minds were proving hard to break into. ‘There’s so many pathways that lead to the heart’ – ‘Heart of Song,’ Josef K. There was only one answer, which was that I needed to find some people with whom I shared a musical taste. Once again, a trip into the big city was required and thus I visited the erstwhile temple of my youth, the record shop which had been the womb, the theatre of dreams, and the hanging gardens of Babylon all mixed up for me as youth. It was called Revolver Records in Bristol and though by now it had lost its former glory, there was a ‘musicians wanted’ board in the entranceway which seemed my best bet. I peeled off a piece of paper that seemed a possibility and bravely made the call. The audition that followed was the antithesis of that with the local gigging band. Mainly, I think, because I was the only candidate. But also because the band’s songwriter and Kim Jong Un-style leader was also supremely taken by my drum kit. A great deal of the band's time and effort was devoted to its image and my silver drum kit, with the addition of the band’s logo on the bass drum, fitted in perfectly. I had a lot of things in common personally with the band leader, too, and though the rest of the group routinely quizzed me on the details of the bands I had claimed to have previously played in in order to blag the position (and despite the absurdity of the names that I gave them, which I couldn't remember from week to week), they couldn't quite bring themselves to openly accuse me of being a fraud while the band leader resolutely supported me. That said, I still had my challenges as he would routinely refer to specific Beatles or Motown songs to guide my style and I would continue with my 1234 punk bash, completely ignorant of the references, and try not to catch anyone's eyes while I turned ‘Pet Sounds’ into The Lurkers. But we rehearsed weekly and I was gradually able to gain more confidence without ever really growing as a musician. We played a few gigs but being in the background behind the rest of the band playing somebody else's songs on a small dark stage to a handful of people, I still had very little sense of entering strangers’ minds. The big exception to this was the night we supported Edwyn Collins (erstwhile label-mate of Josef K, of course) during the time when Paul Cook from the Sex Pistols was his drummer. Paul Cook also deeply admired my kit, and of course particularly the cymbals. I hadn’t made it into strangers’ minds, but I had hung out, albeit shyly, awkwardly and briefly, with strangers who lived in my mind, which was something. It was quite soon after that that a Jack-The-Lad TV producer somehow persuaded our local independent network to finance the recording of a season of late-night music shows based on ‘battle of the bands’ type format and my bandleader’s meticulous attention to presentation secured a slot. Not only did the budget reach to us playing live in the studio with a multi-camera setup, but also to the making of a video where I mimed both playing and singing, wearing clothes supplied to me by our band leader, none of my own wardrobe being deemed adequate. Between the experiences of being on TV, making a video and having Paul Cook admire my cymbals, I felt like I had begun to get a tiny bit of this ‘making music’-stuff right, albeit wearing someone else’s clothes. But it's always when you're most confident that you are most likely to fail. And so it transpired: two unconnected events knocked me off my perch for good. The first was that although we had failed to win our heat in the battle of the bands, the producer had somehow blagged even more money from the station to make documentaries about local songwriters and our bandleader had impressed enough to be the subject of one of those. Although the focus was very much on the songwriter rather than the band, I got a call one day to say that recording was about to start and could I come in urgently with my drums. It felt like my true chance might have arrived at last. The disappointment and embarrassment I felt, having lovingly constructed my shiny, silver kit with the fabulous cymbals in the big television studios and waited excitedly, polishing my drumsticks, only to discover that the drums, not me, were all that were required, lives with me to this day. My kit was, I discovered, a key visual aid and I was commanded to be silent so as not to interrupt the takes, while it shone in the background. The minds of strangers had no room for me, just my pretty drumkit. ‘Please don’t worry/ If you can’t find the words’ – ‘Final Request’, Josef K. At some point around this debacle, I had begun dating the woman who would later become my first wife. At the time, she lived in a run-down rented terraced house in Bridgwater where I worked as a teacher. One night, having either played a gig or been to a rehearsal, I stayed over, parking my car in the street outside with the drums in the back. When I woke in the morning to drive the very short trip to work, I scampered up and down the road confused as to the location of my car. Of course, it dawned fairly quickly in my head that it had been stolen, but my heart refused to believe it as I ran more and more frantically up and down the lane. The car itself was barely above scrappage level, but it contained my now-legendary kit. Eventually acknowledging the horror and, having phoned the police to be met with indifference, I walked to work. Several days later, I got a call from the police saying they had found my car on a housing estate and that I should get there quickly. It was unlocked and although it was already stripped of most things you could readily strip from a car, such as the radio and possibly some tyres, there was the ongoing likelihood that every minute that went by something else would go missing. I asked the police whether they could not, in some way, secure or keep watch over it to make sure that I suffered no further losses, and the officer actually laughed down the phone at the absurdity of the suggestion that he might help in any way. In fact, they gave the strong impression that they themselves were not comfortable visiting the location of the car if possible. My dad, of course, drove me there, and I went back to being a child for a few hours. I think it was still drivable, but it might well not have been. It guess it was written off, but the details are lost to time. What hurt me most then, and what remains with me to this day, was that my drum kit was gone. I do recall ringing round second-hand music shops asking if any of them had been offered a beautiful silver Pearl drum kit with sparkling cymbals, but of course once the word ‘stolen’ was mentioned, the conversations swiftly ended. ‘Next time I come here,’ he said to himself, ‘I must either bring sweets with me to make them like me or a stick to hit them with.’- Franz Kafka, ‘The Trial’. The kit wasn't insured, of course, and so it was that I turned up to the next band practice with nothing but a pair of drumsticks and an apologetic smile. I had neither the resources nor the appetite to replace the kit and although I bizarrely struggled on for a few rehearsals after that, the inevitable truth that it was my drums rather than my musical skills which was really valued by the band eventually came to the fore. I don't remember being fired and I don't remember quitting but my time with the band ended nonetheless and with it my musical dream to meet the minds of strangers seemed forever destined to failure. For Josef K, ‘Becoming famous was never the main priority. But by making music they loved, TV Art hoped that for a time at least, they could escape the dreaded rat race. The alternative seemed pointless. There is little that unsettles the teenage [or middle-aged] mind more than being knee deep in a dead-end job, gradually beginning to resemble everything you’ve ever despised.’ Johnstone shows how Josef K’s members lacked perhaps either the driven ambition or the self-confidence to keep clinging on when the pole of success started getting too greasy: ‘They were too self-effacing - some might even say too humble - for all of that. They were far too grounded. Perhaps it was a defence mechanism. What if everything falls apart? Maybe we should be ready for that?’ ‘In interviews, their apparent moroseness and reservedness didn’t help their cause at all; they were so anxious lest they appear as false, egotistical, or, worst of all, ‘sell-yer-soul for-a-pound’ glory hunters that they sometimes came across as taciturn, possibly at times even dull. More on point, they couldn’t even bring themselves to speak to one another when things weren’t working out. They were too polite, too anxious to rock the boat.’ With the benefit of hindsight, the ‘classic’ Josef K song consists of some quite unique features which I don’t think even the band appreciated at the time. Democracy, or ‘citizenship,’ is key. There’s a knife-edge rhythm guitar that personifies anxiety, that propels the tune, and sometimes takes your breath away with its chops and changes, often almost ear-splittingly trebly, sometimes moodily bronzed. The song will have two or three separate hooks - forensically-constructed, angst-drenched guitar lines; not solos, but with a similar kick, a lead guitar that doesn’t seek to be the centre of attention. There will be a bubbling, rubbery bass that sometimes funks it along with the rhythm, and sometimes takes on the same ‘lead but not lead’ melodic function as the guitar, and then a drum kit that does a bit of everything the rest of the instruments do, sometimes adding fills that are crucial for the meaning of the song. The vocals never seem to be the principal focus of the song, but another one of the five equal parts that make up the whole, and the overall sound always matches the mood and the key words in the song. For all the lack of harmony of ambition and taste explored in Johnstone’s book, Josef K at their best present as a supremely democratic band, one where, more than almost any other band ever, all parts are equal. That and riffs to die for (just listen to ’16 Years’ and imagine how massive an anthem it would be played in heavy rock fashion by some tough Americans in denim…). When the production loses this democracy, or where the original arrangements weren’t right, the songs suffer. That’s not to say you can’t love individual bits of songs – that deliciously despairing fretboard-mangling on ‘Final Request,’ or the sublime use of cymbals on ‘It’s Kinda Funny’, for example. But where the bass, or the lead guitar, or the vocals or the drums somehow stand out more than other instruments in the mix, the delicate, fervid balance of a Josef K song, which is always like watching a tightrope walker on a high wire, is lost. That’s why the version of ‘The Angle’ on The Farewell Single is so much better than the one on the album, for example. Josef K couldn’t tell what worked and what didn’t: the starkly competing voices of bandmates, fans, management, record company, and journalists are clearly displayed in the book and it’s clear that none of them either could agree which sound they preferred. How else can you explain why the first version of ‘It’s Kinda Funny’ was far better than the one they actually released on their album, whereas ‘Fun’n’Frenzy’ is much superior the second time round? They knew they had gold in their fingertips, but they didn’t know how to make it appear on demand, or how to sell it when it did. How else can you explain the difference between the versions of ‘Citizens’ on the first and second albums, or the incredible journey from ‘Radio Drill Time’ to ‘Heart of Song’ (both of which are brilliant, by the way)? ‘The passage of time/ Can change anything, like the feelings we find’ – ‘It’s Kinda Funny,’ Josef K. ‘The Trial is one of the great works of twentieth-century literature, but it was never completed, and, like the author’s other novels, remains a mystery unsolved. The ending of the published manuscript is startling and unsettling but, in some ways, deeply unsatisfying, if only because the reader can never be certain of the author’s true intentions for the finale. It seems apt then that Josef K’s career ended in such a similarly abrupt fashion, and it can be tempting to invent our own ending to a story that seemed to have only just begun.’ – Johnstone. Josef K popped into the minds of strangers then disappeared through the crack in the wall. I meanwhile lurked for a few seconds on the fringes of other people’s minds, like someone hesitating outside the door of a party, unsure whether to knock and go in, then I turned round and went home again. ‘But have I seen/ The art of things to come?’ – ‘Pictures (of Cindy)’, Josef K. Ultimately, life being what it is, I did end up making an impression on the minds of strangers through my music-making endeavours. Just not in the way I had envisaged. And it all started with the theft of the drums, at the very moment it ended. When I finally got to work on that day my car was stolen, I arrived in a great deal of pain. Some muscles in my back had gone into spasm. This had happened several times before but on this occasion the pain was so bad that I couldn’t stand and it wasn't long before I was sent home. Several days later, I was stopped in the corridor by a student who asked me about the events of the day. Word had got around: my life had entered the minds of strangers, but in a Chinese-whispers sort of way. The story that was doing the rounds was that I had chased after the criminals as they drove my car away and in doing so hurt my back, possibly by hanging on to the boot, or possibly even by physically tackling the thieves. Somehow, this further transmuted not long after, into the suggestion that I had once been a professional boxer, which was why I had been bold enough to tackle the thieves. I was asked this first by an incredulous and muscular Year 11 boy I taught and the idea was so patently absurd that I of course confirmed that it was true. He didn't believe it, of course, and shrewdly asked me what weight division I had fought in, expecting to catch me out. As I stalled for time, one of his crew quipped ‘paperweight’ and the ensuing laughter bought me the time to adopt the strategy of pretending I was too humble to talk about it. Before the end of the month young students I'd never met before would be coming up to enquire about my boxing career. Years later still, students I had never spoken to, and who weren’t even at secondary school when my drums were stolen, would sidle up to me in the playground to ask me about my younger days in the fight game, always with that same initial mix of doubt and respect. My drumming finally enabled me to make my mind my mark in the minds of strangers. Albeit as an imaginary boxer. ‘In the end, the question of who or what Josef K might have become hardly matters. And the more time passes, the more of a miracle it seems that they were at all.’ – Johnstone.

Also In In Dreams Begins Responsibilities

In Dreams Begin Responsibilities (2023)

In Dreams Begin Responsibilities (2023)

In Dreams Begin Responsibilities (2023)

In Dreams Begin Responsibilities (2023)

most viewed articles

current edition

John McKay - InterviewCathode Ray - Interview

Robert Forster - Interview

When Rivers Meet - Waterfront, Norwich, 29/5/2025

Spear Of Destiny - Interview

Fiona Hutchings - Interview

Carl Ewens - David Bowie 1964 to 1982 On Track: Every Album, Every Song

Chris Wade - Interview

Shrag - Huw Stephens Session 08.12.10 and Marc Riley Session 21.03.12

Brian Wilson - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

previous editions

Heavenly - P.U.N.K. Girl EPBoomtown Rats - Ten Songs That Made Me Love....

Manic Street Preachers - (Gig of a Lifetime) Millennium Stadium, Cardiff, December 1999

Allan Clarke - Interview

Oasis - Oasis, Earl's Court, London, 1995

Barrie Barlow - Interview

Beautiful South - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

Pixies - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

Chuck Prophet - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

Dwina Gibb - Interview

most viewed reviews

current edition

Peter Doolan - I Am a Tree Rooted to the Spot and a Snake Moves Around Me,in a CircleVinny Peculiar - Things Too Long Left Unsaid

Garbage - Let All That We Imagine Be The Light

Vultures - Liz Kershaw Session 16.06.88

John McKay - Sixes and #Sevens

Little Simz - Lotus

HAIM - I Quit

Pulp - More

Lapsley - I'm a Hurricane, I'm a Woman In Love

Billy Nomates - Metalhorse

Pennyblackmusic Regular Contributors

Adrian Janes

Amanda J. Window

Andrew Twambley

Anthony Dhanendran

Benjamin Howarth

Cila Warncke

Daniel Cressey

Darren Aston

Dastardly

Dave Goodwin

Denzil Watson

Dominic B. Simpson

Eoghan Lyng

Fiona Hutchings

Harry Sherriff

Helen Tipping

Jamie Rowland

John Clarkson

Julie Cruickshank

Kimberly Bright

Lisa Torem

Maarten Schiethart