In Dreams Begin Responsibilities - Heaven Is Whenever We Can Get Together 3 - ‘Certain songs, they get so scratched into our souls.’

by Steve Miles

published: 5 / 12 / 2023

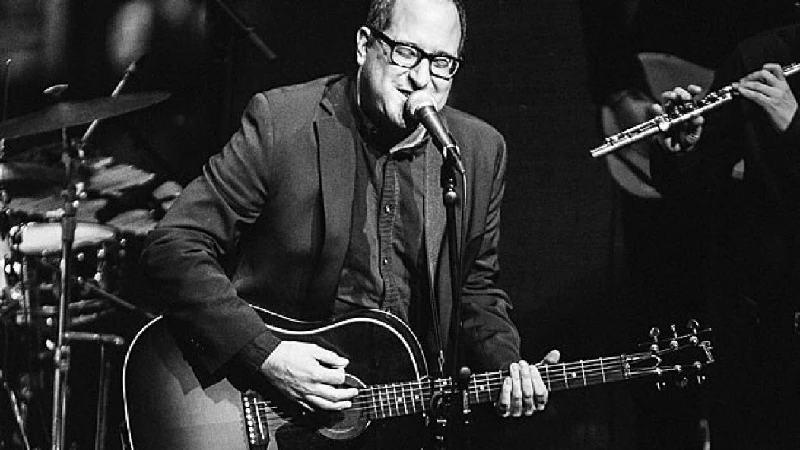

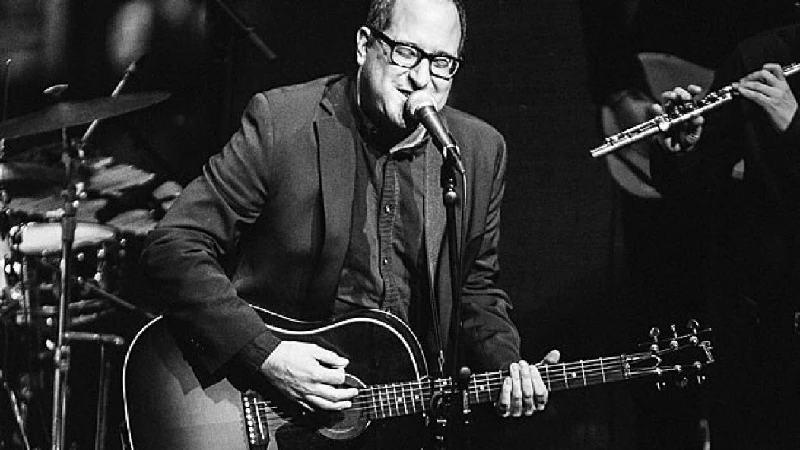

In this third part of a special article spread over four pieces, Steve Miles discusses the role of intimacy and belonging in music: how musicians and songwriters create a special sense of closeness with their audiences, and vice versa, whilst at the same time understanding that intimacy can sometimes elude even the tightest daily relationships. In this third part, he contemplates confessional and narrative writing with Craig Finn of The Hold Steady and ponders the bonds between mental health and music. The last article finished by voyeuristically peering at the Dandy Warhols’ unbreakable cool. Which, rather obscurely, brings us back to The Hold Steady, because they are a band who, to me, also exude a kind of unfamiliar fascination for a world that clearly borders, but is notably different from, my own. Although the world they depict, and the way they deliver it, is in many ways the opposite of the bohemian rhapsody of the Dandy Warhols, the allure of the different is no less strong. In talking to Craig Finn, I rather sheepishly confessed that his America seemed more alien to me than the America I recognise from, say, Lou Reed or Iggy Pop. I posited that this was because his lyrics are littered with in-jokes, ongoing internal references, urban slang and obscure place names that lend a special kind of authenticity and life to his characters and their narratives. It is his forensic deployment of small details, specific places and culturally-specific words that make his songs so literary and affecting. Is it that the things that keep you at arm’s length also draw you in, I suggested? ‘Yeah, I think that what you're saying is true. One of the appeals of the band is that you might have to work for it a little bit, you know? So you can say, ‘Oh, I discovered that!’ It feels like you've got a window into another world. And when something clicks sometimes, if you look something up or you realise something you never knew before,’ he chuckles, ‘then there's a little dopamine there!’ ‘I've always loved geography, you know, even before I loved rock and roll. I love maps and places and learning about state capitals or countries or flags, even. When we first started touring overseas, I remember wondering if people would have a hard time with that. And then I realised that if I'm doing my job right - you know, if I mentioned a street corner in Minneapolis - hopefully I'm getting at something universal that people can get. I mean, another English reference I tend to bring up is ‘Sten guns in Knightsbridge’ (from the B’ side of ‘White Riot’, 1977). I didn't know what that meant, but it sure sounded exciting! Or ‘Dial 999’ (from ‘London’s Burning’ on their first album) - I didn't know what that was the first 100 times I sang along with that song! But that kind of thing, if you're doing a good job, it should be universal.’ As for whether the characters he writes about are drawn from his life or not, he jokes, ‘If I wrote about my own life, it would be all about going to the grocery store and the post office, you know?! But when I was younger, particularly being very immersed in hardcore, there were definitely years where I was not directly involved but was the guy in the back of the room kind of keeping eyes and ears open. And as I've gotten older, I've realised that some of my favourite writers - Kerouac comes to mind – are more of a recordist than a participant. I have, for instance, never been arrested. But you know, some of my bandmates probably have. It's more about listening, watching; and those are, I think, talents of mine: I'm a wild eavesdropper! I go on the New York subway with headphones but no music, and I listen to people talk a lot. That's one way to get stories.’ I tell him that many of his characters seem to me to be burdened; they either lack effective awareness of their own emotions or are running from them, running into drink and drugs and bad relationships and making bad choices. ‘Yeah, I think there's a lot of escape, you know,’ he responds. ‘Physically, geographically or spiritually. And I think that impulse to fly, that's kind of a rock and roll thing. I mean, like Springsteen: ‘We're getting out of town,’ right? ‘We're out, give me the convertible, we're driving into the sunset.’ That’s happening with the characters. I think that maybe our journey in here is that we are constantly learning. In middle age, we maybe get better at it. My friends and myself in our 20s were slowly moving across the country, as if that would fix something more than, you know, stopping drinking for 30 minutes. or just sort of being in touch with our own emotions or shortcomings or whatever it may be.’ What Craig Finn defines there is surely a pretty defining characteristic of youth. You can call it running away, or you can call it searching for something better; you can see it as exploration or as denial. But it’s why Jimi Hendrix and Kurt Cobain and Ian Curtis all died young. They looked, they questioned, they strove, they probed, and they found themselves, as well as the world, wanting. Most of us get through it, some of us don’t. Do you consider yourself somebody who writes much more about the darker, deeper sides of life, I asked him? ‘Yeah, I do. I do go there and it’s funny because I do not consider myself… I think we all can get depressed, but I'm not a depressive person. I'm pretty social and I like going out, I like talking to people. I don't like sitting home in a dark room. I like sunlight! I love outdoors! But I guess when I write I am attracted to some of those stories, but I also I like to find some sort of hopeful message in a lot of our songs. And if it's not explicit, I think that that there is sometimes just the thing of like, ‘Okay, if we're going to be singing a song about people who are suffering, or people who are down, then let’s all get in this room together, and sing it together.’ Then we acknowledge that they're suffering, and we acknowledge that suffering is part of the human condition. And we say, ‘That's part of being human: I sometimes feel sad, I sometimes feel downtrodden or discouraged or whatever it is,’ but just the act of doing that together in some way is helpful in itself.’ That's really beautiful, I think. A wonderful quote. It goes back to the sense of kinship explored in Part One of this article, but takes it further, as it adds a context to that sense of community that makes the partying more than just partying, the fellowship more than just the elation that can come from being in a crowd all doing the same thing at the same time – the much-hyped festival vibe. Instead there’s an element of almost-therapy that becomes possible. Craig’s own emotions aren’t obviously foregrounded in his writing. He has the characteristics of a poet, but he’s no John Berryman, the poet who makes a big appearance in one of the band’s most popular songs, ‘Stuck Between Stations’, the first track from 2006’s ‘Boys And Girls In America,’. Berryman was a confessional writer who struggled with alcohol and depression until, at the age of 57, he jumped from the Washington Avenue Bridge in Minneapolis, the core city of Craig’s geographical iconography and the place he grew up. Those biographical references are in his songs, of course, because nobody writes from nowhere, but the urge in Craig Finn is more to speak for, or through, others than to share his own feelings directly in his songs. He’s not a Taylor Swift or a Nick Drake, from whose songs their biography can be constructed, but, like Swift, he tells a good story. I picked, as a perfect example of a literary song to discuss with him, the fifth track of his third solo album, ‘We All Want The Same Things’ (2017), called ‘God In Chicago’. The song lends a line to the album’s title and describes, without any moral judgement or macro-context, a few days in the lives of a couple of unnamed characters, one of whom is the far-from-omniscient narrator. With the big details left unsaid and the little details precisely pinned-down, the song chronicles the way the two main characters find a bittersweet moment of respite from their respective troubles (‘Then she’s on the sidewalk trying to ask for a cigarette from oncoming traffic/ I felt God in the buildings’), snatching a moment of pleasure from the midst of tragedy (‘We kiss in the corridors/ We fumbled with clothing’), and share a small moment of intimacy in a strange place (‘We all want the same things/ And then it was morning’), before returning, as hopeless as before, to where they began, both literally and emotionally (‘We drove back all hungover/ And all the way to Eau Claire, she played with her hair/ Came up on St. Paul and she was sobbing’). I told Craig I thought it was a great piece of writing. ‘Yeah, that was just a weird story I thought of. I kept thinking, we have this opiate crisis here, which is now very much centred around Fentanyl; people die, and I just thought, what about their friends you know, what are the holes that are left behind? And how are those people trying to pick up the pieces? The story came to me quickly: you know, Chicago is about seven hours from Minneapolis where they start out. It's this idea that they've lost a friend to drugs, an overdose, before they’ve even gone to Chicago. That's the nearest big city, you know, and I thought about that juxtaposition of experience versus tragedy and what that might feel like, and, to sort of put them on the quintessential American Road Trip, you know?’ Even though the song’s action is triggered by the death of a young man, there’s also a strong sense of ongoing emptiness in the characters who remain alive? ‘Yeah. I think it's definitely a grief, and not knowing how to react to this loss. And I think that they're already reeling a bit - he's not working… They have this time to get in a car and drive to Chicago, but it's still something they never have done before either. They could have done it a month ago, but this sort of forced them out of their comfort zone.’ When Craig talks about his characters, it’s as if they were real acquaintances of his. They have dimensionality in his world, a back story in his mind, and some sort of genuine place in his heart. And this, I think, goes right back to the beginning of this article, in the first part, because Craig’s characters mean something to him, and they can mean a lot to us too, and yet they don’t really exist; whereas our next-door neighbour, or the bus driver that drops us off at work, or the person behind the checkout till, who we see every day, we know nothing of. Art brings together what real life leaves apart. With Craig talking so much like a novelist, I had to ask him if that was an ambition? ‘I've tried to write longer stuff and I hope I will. But it's a solitary thing, and it's obviously longer. I hope I will, because I read a lot of novels, and I hope before I leave this earth that there'll be a novel with my name on it. But you know, I'm not very close. Let's just put it that way. I tell him that, in my mind, ‘Sixers’, the fifth track on ‘The Price of Progress’ is a novel. It's just a very short novel. ‘I say it as a joke, but it's sort of true. My problem is I keep thinking of these stories and turning them into songs. I have to at least put one, one big one aside for the novel…’ And, I add, do you see yourself as somebody who writes about mental health? ‘Absolutely. I think I'm more and more interested in that. I think people's struggles with mental health are at the heart of all this. I have never been diagnosed with a mental health problem, but I can tell if I don't exercise for a few days, this sort of greyness comes in and I need to go and sweat it off. It's almost like a sun-burning-through-the-clouds kind of feeling. I can't speak for everyone, but I think that if you're not kind of pushing the boulder up the hill, it's rolling down on you. And I think that that's very much an interest in my work. But also, in the last album, and especially this album, I think there's also this idea of late-stage capitalism: I think it's always been there as a backdrop and I've been saying, it's like the backdrop got moved a number of feet forward on this record, and suddenly the characters and the actors and whatever are bumping their elbows against the backdrop! I saw something on the Internet, which is, of course, where a lot of us get information, that we go to therapy, and we talk about our families or our mother, or something like that. But what about the fact that there's this massive income inequality, and people are working really, really hard and not getting ahead? And the system seems gamed against a lot of people - that also might be really related to mental health in the modern age.’ Isn’t it like that Pete Wentz (Fall Out Boy) quote, I asked: ‘If you aren't just a little depressed, then you aren't paying very much attention to what's going on in the world’? ‘ Yeah, but I think there’s recognising that there are issues, and then also saying, this next hour is gonna be amazing. ‘I'm gonna go down, walk my dog into the park and buy some vegetables at the farmers’ market. And to be honest, that's going to be wonderful.’ And so I think it’s what you're letting in at any moment. There's darkness for sure. But I look back on my own life, and I'm a more depressed person if I let it go than I am an anxious person. I don't suffer as much with that. We all have anxiety of course, but if I look back on my own twenties, especially when I was in college, I may have been depressed.’ ‘Certain songs, they get so scratched into our souls’ from The Hold Steady album, ‘Almost Killed Me’ (2004). At this point in the discussion with Craig, even though he was keen to talk about the band’s ninth album, I wanted to take him back to the band’s fifth, ‘Heaven Is Whenever’ (2010), and, in particular, the sixth track on the album, that gives the album its title. ‘The first four records are kind of like epic, epic, epic, epic, and I think like, we didn't know how to do anything else but try to make another epic record, but there's only so much epic-ness you can go to. So we just kept recording music, and in that sense, I'm really proud. Our reaction to it was work - write more, do more. We were really tired when we made that record. When we went to reissue it, I found that it was really funny on paper but I don't think the performances are very joyful, so the jokes kind of fall flat!’ ‘Heaven is whenever/ We can get together/ Sit down on your floor/ And listen to your records.’ ‘We Can Get Together’ is, essentially, about all the things this four-part article has been about: how fans find consolation and comradeship through the music they love; how they can use that shared passion for music to form bonds in real life; and how the bands they love can mean more to them (and the songs they listen to speak can more to their feelings) than their everyday lives. ‘I was thinking when I wrote that lot about my role and how I'd listen to all these records. And that music can really bring us together, which of course is the title - and I think the big message - but also thinking about maybe some of the lives behind the songs: you know, that all these bands are made up of humans.’ In ‘We Can Get Together’, the narrator loves the girl who’s playing him records (or is it because she’s playing him records?). The first three verses trawl through a number of songs that reference ‘heaven’ in different ways, as a kind of shorthand way of exploring different concepts of ‘heaven,’ and simultaneously painting a picture of the prevalence and power of music. Line one mentions ‘Heaven Isn’t Happening,’ and Craig explains, ‘That one's funny. It's a by a band called The Lapse, and they're a Brooklyn or New York band. But the record’s actually called ‘Heaven Ain’t Happenin’, but I didn't like the bad grammar!’ Then it’s Pavement, and in the next verse, Husker Du, and in the third verse, The Psychedelic Furs, Meatloaf, and Utopia (‘They sang ‘Love is the Answer’/ And I think they're probably right’). I asked Craig whether all the bands meant a lot to him, or whether the songs were chosen to fit the themes of the song? ‘I mean Pavement and the Psychedelic Furs I love, but Utopia, maybe not so much, you know, but it was kind of riffing on that idea. And I think by the time we wrote that song, I was kind of thinking about this afterlife: is this idea of enjoying things, rewarding? I guess my thesis in the record was that you're trying to get to that heaven in life. Like, working towards this reward that's much later is not as rewarding as having something that you're enjoying right now, meaning that heaven is possibly here with us in the divine sense, if we are involved in having a positive and enjoyable and beautiful experience with this creation.’ ‘Yeah, I guess at least, at least an 80% me or something like that!’ The first concludes, ‘She said Heavenly was cool/ I think they were from Oxford/ I only had one single/ It was a song about a pure and simple love.’ A big part of the inspiration behind this series of articles is the connection these lines make. Half of Heavenly, Rob and Amelia, play in my band, European Sun (amongst many others). Heavenly’s recent sold out shows were their first since 1996 - when the band folded after twenty-five-year-old Mathew Fletcher, the drummer, and younger brother of lead singer, Amelia, took his own life. Amelia was kind and brave enough to answer a few questions for this piece. She and I are friends now, but I didn’t know her at the time. I never met Mathew or saw the band play, and I don’t own any of their records, so I have no memory of that event or any of the band’s history. But the ‘seven degrees of separation’ factor of me knowing Amelia, her brother’s tragic death, and Craig namechecking them both in a song about the very things this whole article is about, made writing this seem pre-ordained. I asked Craig about the song, and about the link to Heavenly, with both of us nervous about treading on other people’s private lives or giving oxygen to tragic choices. I started by wrongly guessing the Heavenly single that the song says he owned to be ‘Our Love Is Heavenly’ (1990) because that would surely fit the theme. But it turns out, ‘I knew that song. And it is kind of referencing that song. I did have one seven-inch by Heavenly, but it was not that one, it was ‘Space Manatee’ (1996). But I played that all the time, and actually college radio in Minneapolis, when that song came out played Heavenly a lot. So I was hearing that song on the radio, and I bought it. I bought the seven inch, so that, that was again a little poetic licence.’ ‘Space Manatee’ is a shrewdly crafted piece of bubblegum pop; disposable but sweet, wrapped in bright colours and not meant to make you think. Ian Curtis’ death can easily be understood while playing, say, ‘The Eternal’ (1980) with its funereal march and tearful keyboards, backing Curtis’ despairing ‘Cry like a child though these years make me older’. But ‘Space Manatee’ is the soundtrack for riding a bicycle ‘round the ‘poky quaint streets’ of Oxford before picking daisies on a sunlit lawn. And it has absolutely perfect driving drums, that radiate energy and life. ‘I'm flying in the air/ Floating I don't care/ Anywhere with you// Imagine we're caught in outer space/ Sunlight on your face/ You can make it true’. For Craig, I think that made Mathew’s death seem all the more hard to imagine, and difficult to understand. And as he wrote ‘Heaven Is Whenever’ – and the rest of the album – it struck a chord with him. The connection between choice and outcome, joy and despair, and the journey from hopefulness to hopelessness and back informing his songs. The song’s refrain goes, ‘Let it shine down on us all/ Let it warm us from within’ - is that about trying to get heaven here now? ‘Yeah, exactly. Like you know, let's kind of soak up this beauty of this music. And just the idea of listening and music with friends. I think at that time (the period of The Hold Steady’s fifth album) a lot of business things had kind of entered my world and I'd maybe lost sight of some of the pureness of enjoying rock and roll. So it's trying to pin that down and, and have something to aim for, again, something I'd slightly lost. I was reminding myself in some way. ‘I don't really remember exactly writing that song, but there's a song that I kind of love by Built To Spill - I think it's called ‘You're Wrong,’ something like that, and he's kind of calling out these classic rock songs. It’s actually called ‘You Were Right’, and he’s right about the lyrics: ‘You were right when you said we're all just bricks in the wall/ And when you said manic depression's a frustrated mess.’ ‘We were making our fifth record there. And our lives had become very much being on tour. We toured much harder than we do now. And we were going through some stuff. We were having a hard time as a band. There were some substance things happening within the band and some hospitalisation and we were having a hard time making the record, and I started thinking a lot about the lives behind the bands I liked. There was a sense of myself as a rock fan, moving from rock fan to rock band. I was a little overly obsessed in hindsight with us making our fifth record - it felt so daunting, like what band gets to a fifth record? Are you like the establishment now? And so I think actually that particularly record is not my favourite because I feel like I weirdly inhabited this elder statesman role, where I start giving advice to people. I don't think I was in any place to give advice... It's kind of a Jerry Garcia, David Crosby type figure, that spins this sort of hippie knowledge from the front porch. I kept saying, I was that kind of a cosmic philosopher, but I don't think the joke landed a lot. That song is not a joke, though I point out that Craig’s success has far outpaced his ambition, because instead of just sitting down with somebody on the floor, playing the records, he’s managed to achieve that with not just one person in their bedroom, but a whole chunk of people across any number of continents. ‘Yeah, ‘We Can Get Together’ is a song that we do play a lot of the times in the last day of the the weekends that we do, these residencies, because it very much comments on sort of the pureness and the beauty of having these moments and also these friendships and relationships that are around music.’ And right there is the very connection this four-part piece article has been about. But there’s also that shrill note of tragedy in the song, which is the counterpoint of the happiness striven for through and via music: ‘He wasn't just the drummer/ He was someone's little brother’. In the final part of this article we will hear from that ‘someone’, Amelia Fletcher, lead singer of Heavenly, and conclude our look at the love that dare not speak its name between performer and fan.

Also In In Dreams Begins Responsibilities

In Dreams Begin Responsibilities (2024)

In Dreams Begin Responsibilities (2023)

In Dreams Begin Responsibilities (2023)

In Dreams Begin Responsibilities (2023)

Label Articles:-

ACP Recordings (5)Play in YouTube:-

Picture Gallery:-

intro

In the third part of his four part series, Steve Miles continues his interview with Craig Finn of The Hold Steady, putting his writing process under the spotlight, and looking at how focus on mental health plays a key role in the band’s bond with the audience.

most viewed articles

current edition

Carl Ewens - David Bowie 1964 to 1982 On Track: Every Album, Every SongArmory Show - Interview with Richard Jobson

John McKay - Interview

Colin Blunstone - Thalia Hall, Chicago, 16/7/2025

Billie Eilish - O2 Arena, London, 10/7/2025

Bathers - Photoscapes 1

Loft - Interview

Visor Fest - Valencia, Spain, 26/9/2025...27/9/2025

Sir Tim Rice - Interview

Robert Forster - Interview

previous editions

Manic Street Preachers - (Gig of a Lifetime) Millennium Stadium, Cardiff, December 1999Heavenly - P.U.N.K. Girl EP

Beautiful South - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

Peter Perrett - In Dreams Begin Responsibilities Interview Part One

Boomtown Rats - Ten Songs That Made Me Love....

Oasis - Oasis, Earl's Court, London, 1995

Coldplay - Wembley Arena. London, 16/8/2022

Trudie Myerscough-Harris - Interview

Prolapse - Interview

Pixies - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

most viewed reviews

current edition

Davey Woodward - Mumbo in the JumboSick Man of Europe - The Sick Man of Europe

Lucy Spraggan - Other Sides of the Moon

Phew, Erika Kobayashi,, Dieter Moebius - Radium Girls

Suzanne Vega - Flying With Angels

Bush - I Beat Loneliness

Amy Macdonald - Is This What You've Been Waiting For?

Alice Cooper - The Revenge of Alice Cooper

Blueboy - 2

Cynthia Erivo - I Forgive You

Pennyblackmusic Regular Contributors

Adrian Janes

Amanda J. Window

Andrew Twambley

Anthony Dhanendran

Benjamin Howarth

Cila Warncke

Daniel Cressey

Darren Aston

Dastardly

Dave Goodwin

Denzil Watson

Dominic B. Simpson

Eoghan Lyng

Fiona Hutchings

Harry Sherriff

Helen Tipping

Jamie Rowland

John Clarkson

Julie Cruickshank

Kimberly Bright

Lisa Torem

Maarten Schiethart