Zombies - Interview

by Lisa Torem

published: 23 / 10 / 2015

intro

Lisa Torem speaks to Rod Argent, the Zombies' keyboard player/songwriter about songs from their new album, 'Still Got That Hunger', as well as their past classics

“There’s nothing that compares to a good reaction to something that you’ve just done and it’s the new things that fill you with the most energy and the most excitement.” That’s Rod Argent talking with great excitement about the Zombies’ brand new album ‘Still Got That Hunger’, which levies a panorama of truculent riffs, visceral harmonies, focused songwriting and the gifts of versatile Colin Blunstone, whose voice has never sounded stronger. Of course, bassist Jim Rodford, drummer Steve Rodford and lead guitarist Tom Toomey reel the listener in with their dynamic infusions at the same time. The Zombies have acquired a new set of young fans. My daughter, Allie, confides that she’s not sure how to explain it, but she loves the Zombies because they make “real music.” I mention this in our interview. That casual comment triggered a slew of relevant production details: “We’ve very deliberately gone back to a very old way of recording in the way we used to have to, with only four tracks and we very consciously recorded it with the whole rhythm section, playing everything together and with Colin singing the guide vocal and it worked so well that very often that guide vocal turned out to be the master vocal on the album.” “So, the reality is of people making music by listening at the moment to what was going on. You moderate your piano playing to what the drum is doing at that split second. and then he immediately moderates what he’s playing to how you’ve reacted to that. That’s the real way of making music and with the advancements in technology - and I’ve been as guilty as the next person - it’s so much easier to put each part down separately and really concentrate on that part until it is completely right but there is something magical that can happen when you play all together and that is what truly can happen, where the sum can be greater than the parts and you get that moment of magic and it becomes about capturing a performance. There is something magical about that and we really, really tried to do that on this album. That’s a really big compliment to say that the music sounds real because I understand exactly what she’s saying and that’s what we’re after.” But what led up to this celebratory album? Keyboardist Rod Argent, guitarist Paul Atkinson and drummer Hugh Grundy first met up at St. Albans School in 1961. By the following year, bassist Chris White and vocalist Colin Blunstone would complete the line-up and the Zombies would go on to change the face of pop music, with Argent serving as chief songwriter, keyboardist and arranger. Producer Al Kooper urged CBS/Columbia to release ‘Odessey and Oracle’ in 1968 even though the band had broken up a year earlier. The album was a treasure trove of ahead-of-its-time originality, but it was ‘Time of the Season’ which flew up the charts and has since been widely covered. After the Zombies broke up, Rod Argent formed Argent with co-writer/bassist Chris White, releasing hits such as ‘Hold Your Head Up’. After their 1975 break-up, Argent performed and recorded with a succession of artists and recorded solo albums, ‘Moving Home’ and ‘Red House’. In 2001, the Zombies reunited for a benefit and reformed in 2004 with Tom Toomey, Jim Rodford and his son Steve Rodford joining Argent and Blunstone in the line-up. New and early fans continue to flock to their international concerts. They will perform ‘Odessey and Oracle’ in its entirety from September 30 to October 27, 2015 in the United States as well as supporting ‘Still Got That Hunger,’ which features Argent’s evocative and riff-savvy songs, Blunstone’s versatile voice as well as dynamic infusion from the Rodfords and Toomey. In our second interview with the Zombies, Rod Argent spoke about his one-off songwriting and pervasive influences. PB: There’s such a mix of styles on ‘Still Got That Hunger’. I swore I heard Ray Charles, Bach and early Zombies. RA: I wrote nine of the songs and Colin wrote one of them basically over a period of seven months. There was an awful lot going on. We were moving after thirty-eight years in the same house, and up to that point I’d always had a studio where we had recorded albums and other people's albums too. But I didn’t have that. I just had one little keyboard, and you’re right when you say there’s a whole mixture of stuff in there, but in a way that was always the case. Even with ‘She’s Not There’, I was eighteen years old and I just thought I was writing a song like the Beatles, but it came out a lot different and one of the reasons for that was at the same time that I was in love with rock and rock and roll I was also in love with some Miles Davis and classical music, which I’ve never stopped listening to. When I first heard Elvis sing ‘Hound Dog’ and Little Richard and Ray Charles — I’ve never stopped listening to Ray Charles, particularly his early stuff I’ve always loved, and those things were always flying around the songs I wrote really. The first time I met Pat Methany he knocked me out by saying, “‘She’s Not There’ was the song that made me feel that I could go ahead and do what I wanted to do — all that modal stuff,” and I thought, "There’s no modal stuff in ‘She’s Not There’", and when I went away what I thought in my mind was a simple chord sequence, A minor to D, I had constructed this little modal thing to connect the chords together without even thinking about it. All this wonderful music was just flying around and becoming an ingredient in the soup. It sort of finds its way through. So I think the Zombies always had different bits of music. In 'Odessey and Oracle' in ‘Hung Up on a Dream’ there are things all mixed in with the rock and roll. I’m really glad that those things are still alive and kicking and provide some of the ingredients in the soup that we’re still making (Laughs). PB: ‘Little One’ is a very touching but simple arrangement. It’s like you’re taking us to the neighborhood piano bar. RA: We wanted to do just one song that was very intimate, just vocals and piano. It was recorded very quickly. It wasn’t written quickly. Two songs on that album started life about thirty-eight or forty years ago. When my daughter was born, and she’s now forty, I started writing the song. I literally just wrote the first four lines and for some reason I never managed to finish it and then just three years ago she provided us with our one and only grandson, a beautiful little boy, who is just a delight and I thought, "Wouldn’t it be wonderful to just finish this song which was originally written about my daughter but then transfer it to him?" It completes the circle in a way. (Rod sings the first verse.) “Little one, what do you mean to me?/Why do you warm my heart?/Is it just ‘cause you’re mine…?” That was all that was written and then I finished the song this time around. That was one intimate song and the other one was ‘Moving On’. In 1977, along with other musicians in my generation, when we’d heard that Elvis had died, it just hit me like a hammer blow and made me feel, "Oh, no, what’s going to happen?" This really feels like a ship without a rudder, which is where the first couple of lines came from - “I’m moving on like a ship getting windblown.” The original line was, “August moon/Can you tell me where I’m bound?” That became “April moon/Can you tell me where I’m bound?” Those were the original lines that were written and again I never took that any further. The idea for that song always stayed in my mind and I thought, "Why don’t I revisit it and see where it goes?" It’s no longer about Elvis now. It’s about whatever it means to the person who hears it. It does have some touchstones to my own experiences in there as well and I was really pleased that I could finish it. I loved the way it turned out and I love the way that Colin sang it. Those were the two songs in the album that started life very many years ago but were really written this year. PB: I’ve seen you perform and you really do some mind-blowing solos. What goes through your mind as you’re creating those solos? RA: (Laughs). Wow. What a question. When you play a song again and again and again, what was originally improvised gets into a sort of steady pattern but I always try something different in the solo. I quite often like to try to start differently. I never did that on ‘Hold Your Head Up’ with the beginning of the solo. That is because I like to do it like it is on the ‘All Together Now’ album because I really love that style and it’s become a trademark, but I’ll very often take it to different places, but what goes through my mind? It’s difficult to know. On the very best nights, where you feel that you’re just flying, your mind is a blank canvas and you can suddenly find yourself going somewhere where you haven’t gone before, I love that. I really love that. Very often then in later days, what you’ve done completely spontaneously becomes part of the pattern of the solo as well. But I always try and think of something original at some point during each of the solos and just see where it goes from there. Sometimes you’re a bit more inspired than others. It’s not magical really but there’s something a little bit magical about that. It’s your subconscious completely taking over, and it’s wonderful because the other people in the band are responding to that, and it’s something they haven’t heard before, and they put their own input into that as well, and it’s that part of music making that makes you feel like it’s such a privilege to do it, and you live for those moments really. PB: Sometimes it seems that you have used literary techniques to pen your classics. The ‘Tell Her No’ verse is in third person — “And if she tries to tell you, she loves you…” - and then the story shifts to first person—“Don’t hurt me now, don’t hurt me.” That transition creates a very emotional mood. RA: All those songs, lyrically, were written fairly quickly and again it’s the subconscious coming in. Writing in third person — I don’t know where that came from. It’s something the Beatles used to do in ‘She Loves You’, rather than writing from a personal standpoint. But I don’t know. I’ve never thought about that before in ‘Tell Her No’. I can tell you that ‘Tell Her No’ to some degree was written as a result of hearing some Burt Bacharach songs because for the first time that I was aware of in that era of pop music, rather than using straight chords or a bluesy version of chords and using blue notes, he was using more augmented chords, chords with added harmonics on them. For the first time I heard someone using major sevenths and major ninths and even elevenths and thirteenths in chords and because I love jazz as soon as I heard that I thought, "I’ve got to have a bit of that", so there are actually thirteenth chords in ‘Tell Her No’. It starts off with a major seventh and major ninth chords and it was a response to hearing Burt Bacharach songs, where he used all those added harmonics on chords and, of course, they were built up beyond the major chords that were most often used in pop music. But lyrically I’ve never thought about what you were saying. PB: ‘A Rose For Emily’ is about a girl left behind but there is also something mysterious about the lyric. ‘She’s Not There’ has that ambiguity. Fans still debate the actual meaning. One person wrote about changing gender and used ‘She’s Not There’ as a title and fans wonder if it is about a girl with mental problems or one who wants to avoid entanglements. Do you ever think, “I’m going to dangle or weave a mysterious thread in the lyric?” RA: Colin did an album and Bernie Taupin wrote one of the songs lyrically, and Colin asked, "What’s the song about, Bernie?" and he said it’s about whatever it means to you, wherever you make that contact. If the song has got anything about it, it starts off with the writer touching something, which means something to him or her, but if it’s a good song people will find common reference points to apply to their own experience and they can interpret it according to their own experience. That’s the magic of songs really. Quite often when I write a song I’ll start with an idea or a mood or a feeling or something I want to capture, but I’ll start from a point and let it develop itself. A classic example is a story song like ‘Care of Cell 44’. I started with: “Good morning to you/I hope you’re feeling better, baby/ Thinking about me while you are far away.” I started with those two lines, which are quite an ordinary thing in a way — people are separated. In my mind I just wrote the story and then it developed itself and became a prison song. It developed as I was writing it and I’ve always loved that. 'A Rose for Emily’ was written because I’d just read a William Faulkner short story, ‘A Rose for Emily.’ There was something about the title I’d found incredibly evocative. My song was nothing to do with Faulkner’s story, not one percent, but I loved the title and the mood that it evoked and what could the story be behind the title? What other story could there be? I just let it weave itself really from that point. ‘She’s Not There’ was the second song I wrote and I literally wrote it in the recording session and I thought, "Where am I going to start it?" I had some really musical things in my mind that I wanted to incorporate. I wanted it to be fairly bluesy — actually, melodically; the verse is based around the blues scale. Secondly I wanted it to develop modally, to build and end on a real climax, and I had this idea of starting in a minor key and ending in a major key and then falling back to minor again. I started by just throwing on some old blues albums. I put a John Lee Hooker album on and the opening track on the album was ‘No one Told Me'. Now I have to confess that nothing about the song has anything to do with the John Lee Hooker song, but that first phrase, "No one told me/It’s just a feeling I had" — I just loved the way the phrase tripped off the tongue. I thought, "It’s got a movement about it", and I applied that to a little blues scale and again I just let the story develop in my own mind up to the climax, and musically it seemed to underline what was happening in the story and going from that climax, "She’s not there", and back to the minor to be more moody again and to start telling the second part of the story. So, that’s how it was built. It wasn’t built around any specific incident that happened to me; nothing really personal. ‘Little One’ is personal and, strangely, almost everything on ‘Still Got That Hunger’ is personal, but not things that I could always explain, some very personal things which I like to try to expand into things that people might relate to in a more universal way. PB: The Zombies will soon perform ‘Odessey and Oracle’ in the U.S. RA: The idea was from Chris White, the original bass player. Our band was getting more and more immersed in our Zombies' stuff and he used to come along. He loved the idea that we were keeping the whole thing alive, and he said, "I would love to have all the original surviving members play ‘Odessey and Oracle’ from start to finish" so we put together a night in London, which turned into three because it sold out very quickly. When we recorded ‘Odessey and Oracle,’ we overdubbed Mellotron parts and additional harmonies. About half the songs work with just five people, but the rest of the songs, 100 percent, absolutely need the extra Mellotron double keyboard part and the extra harmonies to work. ‘Brief Candles,’ ‘Hung Up on a Dream,’ ‘Changes’ don’t work without them so we thought, "If we’re going to do this in London, we’re going to reproduce every single note," and I even went out and bought an 1890s Victorian pump organ so that we could replicate exactly ‘Butcher’s Tale’ when Chris did it — he sings with a harmonium accompaniment. When it was put to us that we could do it in the States, which is always much more difficult, we got an extra musician to play the second keyboard part, which I originally played, and there were extra members to do the other harmonies. It means taking a lot more people on the road and the production values are higher. For a long time, we didn’t see how we could do this economically, but it is happening now. The first part of the evening runs for about forty five minutes to an hour with our normal band, doing at least four or five songs from the new album along with some Zombies’ perennials like ‘She’s Not There’ and ‘Tell Her No’. and maybe one or two other songs and we’ll probably do ‘Hold Your Head Up’ because Chris White wrote that song and he’ll be there all evening. He never played it, but he wrote the majority of it. And the second half will be the full production with everybody involved on ‘Odessey and Oracle’, where we hope to replicate every single note that was on the original album. PB: ‘Time of the Season’ continues to get covered by choir groups, indie and rap artists. What inspired the iconic breathy hook? RA: Indirectly if you want to go back, it comes from the Beatles. They often would say that ‘She’s Not There’ comes from the Beatles because, what I always adored about Ringo’s drumming was, he would often put a very broken rhythm into the verses and I didn’t know anyone else who did that as on ‘Ticket to Ride’ and ‘Not a Second Time.’ It was this very inventive, broken drum rhythm for the verses and then he’d go into something more straight-ahead and I loved that. On ‘She’s Not There,’ that rhythm that I wrote with the song, the drum and the bass wasn’t a copy of anything Ringo had done. The idea of that broken rhythm was because I had heard the Beatles doing that, and the other thing that they used to do was they often used mouth noises or they would hit a cardboard box to make a percussion thing ,and I thought, "Why don’t we do this on ‘Time of the Season’?" We rehearsed it without that, and then when we were recording it I said, "I’m just going to do a bit of that ‘ahhh'." It was mouth percussion, really. It was a very quick idea and it worked immediately. PB: Did you know in advance that Eminem wanted to sample ‘Time of the Season?’ RA: I had absolutely no idea until our publisher sent an email, "Eminem’s recording a sample of ‘Time of the Season’. Will you give us permission?" and he used so much of it that he gave me fifty percent of it basically and I said, "Okay, can you send it over? We’d like to hear it," and he said, "No, no, Eminem’s very protective about what goes out." So I said, "How can I approve it if I haven’t heard it?" In the end, he gave me a link, which expired after a couple of hours, and, honestly, I loved it. What I loved about it was the fact that it wasn’t just a copy of the song. It’s lovely, brilliant, but he used so much of ‘Time of the Season’ and in the lyrics he used a very much sound-alike phrase — "There’s no rhyme or no reason for nothing” and “It’s the time of the season for loving". It was very close in sound and yet inverted the sentiment totally, so that’s really clever. I’m not a great fan of rap but to have something that‘s so inventive but also such a modern genre but using something that I’d done, and which we’d done so long ago, was very flattering. PB: What was it like recording with the Who? PB: The Who, in my opinion, are one of the most fantastic groups. Pete Townshend is hugely inventive and just great. I’d been asked to do an album with Roger Daltrey. I played keyboards on an album called ‘One of the Boys’. Roger liked what I had done and so he spoke to Pete and asked me, "Would you do the whole album?" which was 'Who Are You'. So, Pete sent me a cassette of Pete demoing the whole album, which is brilliant. I hadn’t heard it for a long time. The original idea was that I would do the whole album, but it took so long to get the first three tracks done because there was a lot going on politically, I think, and so the guys would come in and they’d have been ensconced in meetings the whole day, and it took time to get down to the actual recording because they were incorporating it with business. I’d also agreed to do something for Andrew Lloyd Webber on ‘Variations’, which became a number one album in the UK. I’d agreed to do this, and the time ran out. I told Pete, "I’ve got to do Andrew’s album now," and he asked, "Which album would you rather do?"’ and I said, "It’s got nothing to do with that. I agreed and I can’t renege," and so in the end I only did three tracks, which, in the end, I’m not credited on, but that’s me playing piano and I played synth on a Jon Anderson number. The actual recording didn’t take long. We did ‘Who Are You’ in an afternoon and ‘Love is Coming Down’ in an afternoon. I can’t believe in the end that we were there for so many days and only ended up playing three songs, but that’s what happened. PB: What was it like working with Ringo’s All-Starr Band? RA: His people had asked me before but the timetable just didn’t work out, but this particular year it did. I’ve always genuinely loved Ringo’s drumming. There’s a feel to his drumming, a slight swing, which I’ve always loved and it was a great experience. It was touring in a way that I didn’t know still existed, private jets and, like the Beatles, running off the stage at the end of the night not even into the dressing room — it was like ‘A Hard Day’s Night’ — straight into the limos where the roadies had collected all the stuff from the dressing room and packed it for you — it was all in the limo, straight to the private plane and maybe back 400 miles to where your hotel was and by midnight you were back. That was quite fun. I shared a dressing room with Edgar Winter, a monster musician, and that was a joy and Sheila E. on principal percussion, Hamish Stuart from the Average White Band and Paul McCartney who is a great bass player, Richard Marx and Billy Squire. It was a great thing to do. His people have enquired since then to see if I would be available, but then again it may never work out because the work I’m doing with the Zombies has gone up and up. It’s great. I’m not complaining, but it leaves little time for anything else. PB: What were some early musical memories? RA: I was in a really good cathedral choir, which was a huge exposure to music. That’s where I first heard and fell in love with Bach and then when I was eleven, my cousin, Jim, who plays bass with us now, played me ‘Hound Dog’ and I absolutely flipped, and for six months I just wanted to hear the most raucous rock ‘n’ roll to my parents’ complete horror. But at the same time, I thought, there’s no reason to stop listening to Stravinsky and everything else that was going on. I desperately wanted to learn to play the piano. My dad was a semi-pro pianist in a dance band from the age of 17 to 83 but he never used to play in the house, but he was happiest when he was playing. I think that rubbed off on me as well. I was self-taught but the background of being in the cathedral choir gave me a fantastic feel for harmony, because there was wonderful harmony going on around you all the time and that was a big help, being able to naturally hear where harmonies should be. I always had the ability that when I heard a melody even before I was taught anything that I could always play it on the piano or on any instrument you gave me, because I could picture somehow the gradations of the scale in my mind, whether they were whole notes or half notes. I just knew where the leaps were and where you had to go. I’ve always been able to do that. If I hear something now, I can picture the melody in my mind and play it instantly. I’m sure I’m not the only person who’s done that, but that was something that was a bit of a gift in a way, a bit of flair that not everybody has. PB: If you could repeat one day in your life, what would it be? RA: I would have to say something personal. I am going to choose the day that I got married. I’ve been with my wife, Cathy, for forty-three years now, and we’re still just as happy as we were when we first got married and so that’s been a brilliant thing to have happened in my life. PB: Thank you.

Band Links:-

https://www.thezombiesmusic.com/https://en-gb.facebook.com/thezombiesmusic/

https://twitter.com/TheZombiesMusic

http://www.colinblunstone.net/

https://en-gb.facebook.com/colinblunstone

https://twitter.com/colinblunstone

Have a Listen:-

Picture Gallery:-

interviews |

|

Interview (2024) |

|

| Vocalist Colin Blunstone talks to Lisa Torem about the Zombies’ upcoming UK and US tours, special guests and how the music business has changed since the Sixties. |

| Interview with Rod Argent (2023) |

| Interview (2021) |

| Interview (2020) |

| Interview with Colin Blunstone (2018) |

| Interview (2016) |

| Interview (2016) |

| Interview (2011) |

profiles |

|

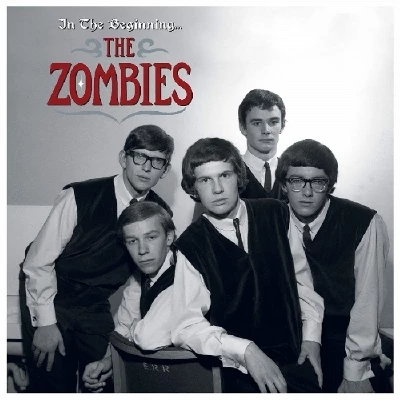

In the Beginning (2019) |

|

| Adam Coxon profiles 'In the Beginning', a new five LP vinyl only only box set of early Zombies recordings. |

live reviews |

|

Old Town School of Folk Music, Chicago, 1/7/2022 |

|

| After a two-year lockdown, The Zombies rose above adversity to tour and celebrate their 2019 Hall of Fame induction. Lisa Torem at the Old Town School of Folk Music in Chicago enjoys both the classics and new tunes. |

| City Winery, Chicago, 20/3/2018 |

| Mayne Stage, Chicago, 1/8/2012 |

| Ferry, Glasgow, 19/11/2011 |

photography |

|

Photoscapes (2015) |

|

| Darren Aston takes photographs of iconic 60's band the Zombies at the Arts Club in Liverpool |

reviews |

|

Breathe Out Breathe In (2011) |

|

| Occasionally effective latest album from influential 60's act the Zombies, which, however, doesn't unfortunately match up to the classic work of their past |

most viewed articles

current edition

Carl Ewens - David Bowie 1964 to 1982 On Track: Every Album, Every SongArmory Show - Interview with Richard Jobson

Colin Blunstone - Thalia Hall, Chicago, 16/7/2025

John McKay - Interview

Visor Fest - Valencia, Spain, 26/9/2025...27/9/2025

Bathers - Photoscapes 1

Billie Eilish - O2 Arena, London, 10/7/2025

Loft - Interview

Robert Forster - Interview

Sir Tim Rice - Interview

previous editions

Heavenly - P.U.N.K. Girl EPManic Street Preachers - (Gig of a Lifetime) Millennium Stadium, Cardiff, December 1999

Beautiful South - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

Oasis - Oasis, Earl's Court, London, 1995

Prolapse - Interview

Peter Perrett - In Dreams Begin Responsibilities Interview Part One

Coldplay - Wembley Arena. London, 16/8/2022

Boomtown Rats - Ten Songs That Made Me Love....

Trudie Myerscough-Harris - Interview

Pixies - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

most viewed reviews

current edition

Sick Man of Europe - The Sick Man of EuropeDavey Woodward - Mumbo in the Jumbo

Amy Macdonald - Is This What You've Been Waiting For?

Lucy Spraggan - Other Sides of the Moon

Phew, Erika Kobayashi,, Dieter Moebius - Radium Girls

Suzanne Vega - Flying With Angels

Bush - I Beat Loneliness

Blueboy - 2

Alice Cooper - The Revenge of Alice Cooper

Cynthia Erivo - I Forgive You

Pennyblackmusic Regular Contributors

Adrian Janes

Amanda J. Window

Andrew Twambley

Anthony Dhanendran

Benjamin Howarth

Cila Warncke

Daniel Cressey

Darren Aston

Dastardly

Dave Goodwin

Denzil Watson

Dominic B. Simpson

Eoghan Lyng

Fiona Hutchings

Harry Sherriff

Helen Tipping

Jamie Rowland

John Clarkson

Julie Cruickshank

Kimberly Bright

Lisa Torem

Maarten Schiethart