Laurence Juber - Interview

by Lisa Torem

published: 13 / 3 / 2012

intro

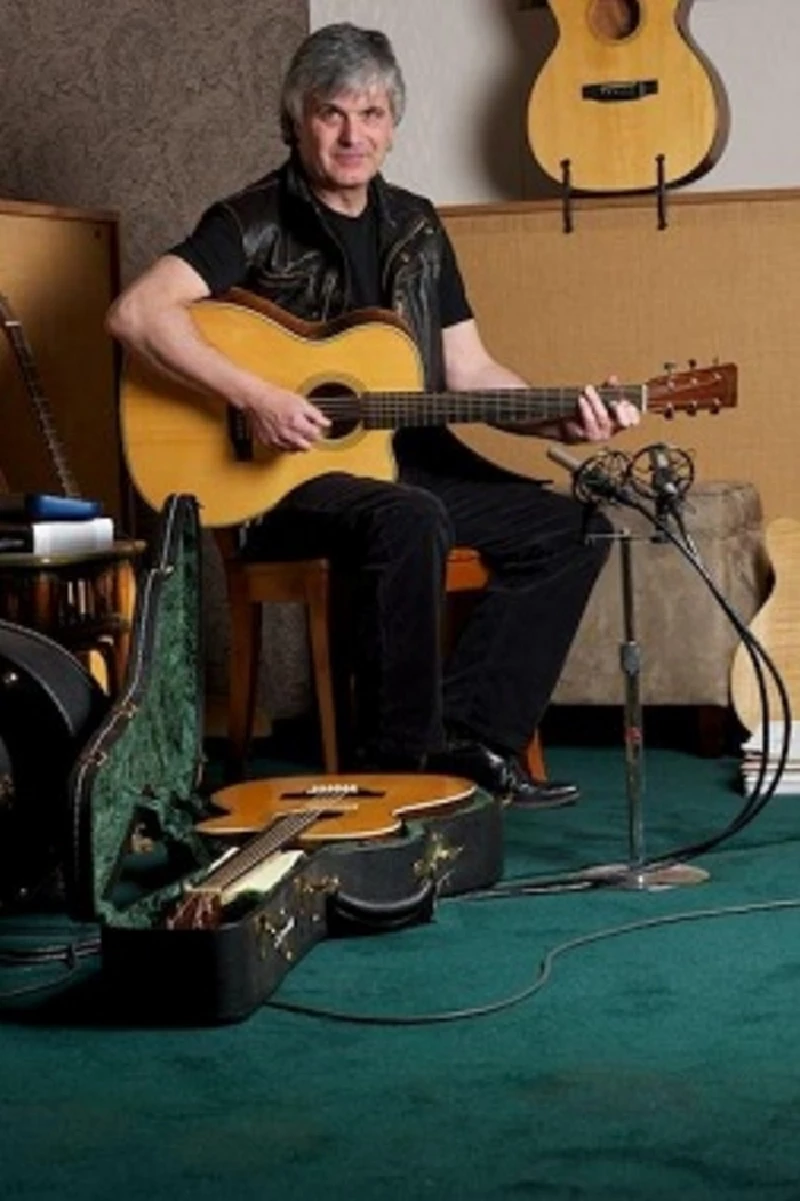

Lisa Torem speaks to former Wings guitarist Laurence Juber about his finger style technique and working with Paul McCartney

The multi-faceted Laurence Juber has written soundtracks for a diverse range of documentaries: one was about the children of migrant workers (NBC Dateline: ‘Children of the Harvest’) and another was about baseball (Ken Burns, ‘The Tenth Inning’). In addition, he has written for contemporary video games, Muppets and, with his wife, Hope, musicals. After the British guitarist/composer solidly established himself as an indispensable, session player, he spent the last two years of the 1970s with Paul McCartney and Wings, grabbing his first Grammy for Best Rock Instrumental in 1979. He earned a second Grammy for his delightful rendition of ‘The Pink Panther’. Juber can currently be found gigging in Unitarian Churches, Midwestern Peace Ranches and Canadian Music Fests, performing original finger style solos or nostalgic covers from the great American songbook. Even after nineteen albums under his belt, the prolific, soft-spoken, nonstop artist still sets his sights on an endless array of future projects. Pennyblackmusic spoke to Laurence Juber about his remarkable background, finger style technique and working with Wings. PB: Did you start your career with classical training? LJ: I studied classical guitar because I had to. I wanted to study music, and in high school the prerequisite for studying music theory was that you had to have a certain grade level of an instrument, and because my instrument was guitar I was a lousy piano player. I took classical guitar lessons at school and got to the sufficient grade level – I think grade 8 was the highest level, but I can’t say that I had a passion for classical guitar. And I certainly would listen to Julian Breem and John Williams; in particular, because those two were the most famous of the English classical guitar. Many years later I worked on a record with John Williams, who did a record in 1977, ‘Travelling’, and had a band called Sky in the 1970s and 1980s, which was kind of a pop classical fusion type thing. And I also had a very nice album by Naseem Amin, called ‘Spanish Guitar’ and, of course, I was familiar with Segovia and would learn some of the Segovia transcriptions. Playing classical guitar was something of a means to an end, but it wasn’t my passion, because my passion was playing guitar in general. My ambition was to be a studio guitar player, so having some classical experience was valuable, and I wanted to study music academically, so I needed that. That was my entrée. PB: On the Cleo Laine project, ‘Born on a Friday’, you worked with John Dankworth and George Martin. Was that your first introduction to jazz? LJ: No, not exactly. I had already been playing with the National Youth Jazz Orchestra and I had worked with John Dankworth then, so it wasn’t entirely new to me. I had been doing jazz gigs around London with various friends and ensembles. The Cleo Laine gig came about because one of the other members of the National Youth Jazz Orchestra, Paul Hart, was Cleo’s piano player at the time. Paul, something of a prodigy who played bass, piano and violin, recommended me for that particular gig, and the fact that George Martin was producing was kind of a bonus. What I was working toward was being a studio musician, and there was a period right after I graduated from London University, where I was suddenly being asked to play on various sessions. That was my intention, but I was still fairly green and just learning the ropes, and I continued to do that right before the point at which I joined Wings. The classical guitar training was useful as was the college education, but the greater experience was the fact that I had learned to read music very early on, even before I learned classical guitar. I did what was necessary in terms of paying my dues around London: demo sessions, understanding music and style, developing certain versatility -- all these things worked together. I continued to take classical lessons while in college, but I was also teaching myself to play Renaissance flute, which, in some respects, had a bigger impact on my technique as a finger style guitarist than the classical technique did. PB: So you played with Wings after having had a certain degree of anonymity in the studio. You had to develop a stage persona. Was that a big shock to your system? LJ: The biggest shock to my system was the fact that my father had passed away in March of 1978, and I was asked to join Wings at the end of April. I was at a point in my life where radical change was kind of just in the air. I had to really think twice about whether or not I would join Wings in the space of a nanosecond. I didn’t want to turn down the offer to work with Paul McCartney because I was a big Beatles fan, though not specifically a Wings fan. My musical interests were very eclectic during that time. But the fact is that it felt like a natural move and my studio experience was very useful in Wings. That wasn’t the radical change. The radical change was getting up on stage and playing with Paul McCartney, not that I had not been onstage as a featured performer before. I had done that, but it wasn’t my ambition. I was kind of a shy teenager and wasn’t really thinking the spotlight. That was a powerful addition to my musical experience -- getting up onstage with Paul. PB: Was your predecessor in Wings Jimmy McCulloch’s performance something you wanted to emulate, or did you say, “I’m doing what I’m doing. I’m going to start clean.” LJ: That’s what I did. There was a coincidence in so far as he played a red Gibson SG and it just happened that the guitar, which I ended up using onstage, was a red Gibson SG, but that was purely coincidental. When we were doing ‘Back to the Egg’, the only reference to anything that would have come before was a video for ‘I’ve Had Enough’, which I believe Jimmy had played on the ‘London Town’ album, and that was a tune also that we would play onstage. That wasn’t my point of reference. Mine was always: what will make this particular song as good as it could be? And what will be just the right creative synergy? The first song we recorded for ‘Back to the Egg’ was the title track – In that first session, we recorded ‘Same Time, Next Year’, the demo for the movie (LT: McCartney wrote the title song for the 1978 American film, but it was not used) and it was a very, broad, orchestrated kind of ‘My Love’ type approach, which was what I would have associated more readily with Wings. We recorded, ‘So Glad to See You Here’ which was really very edgy and then, in the early sessions, we did ‘Spin it On’ which was like punk rockabilly. PB: That was really an adventurous album. LJ: It was an adventurous album. There are people that have had varying opinions about that album and I have my own opinions, but the reality is that there was some very, very creative work that went into that record, and so I just sought to become part of the synergy of it; an integrated member of the band, instead of just being a studio musician brought in to play. The expectation was that we had to think of the band and we did. That album, in particular, really has a band like feel. PB: ‘Rockestra’ was quite epic. You played slide on ‘After The Ball.’ LJ: ‘Rockestra’, that was a rock orchestra. It had a guitar section. The fact that I could look down the line and there was Pete Townshend, Dave Gilmour, Denny Laine, Hank Marvin, John Bonham… A couple of years ago I did a documentary score for NBC in which I played a lot of lap dobro (‘Children of the Harvest’). And I wrote some music for Starcraft, the video game that incorporated some western style slide stuff. PB: What was it like working on ‘Children of the Harvest’ after working with an ensemble? LJ: Well, we’re talking about a period of about thirty years ago. I’ve done much ensemble work since Wings. I moved to New York, did some studio work, and then moved to LA and started raising a family. I became very integrated into the studio scene here. There are hundreds of movies, TV shows and records, and, actually, it’s funny because with Davey Jones passing away just the other day, I could go back and listen to some of the stuff that I’d recorded with the Monkees. So ensemble work is very natural to me. Other than the intensity of being on stage with Paul McCartney, I was used to being in some sort of ensemble; with a jazz band, a rock band, or playing with an orchestra. PB: How did you and Preston Reed, two guitarists fully capable of performing and recording solo, work out guitar arrangements on ‘Groovemasters’? (Solid Air Records). LJ: The whole process took about a week. In my studio, we just did some writing. Preston would play some rhythmic thing and I would add something melodic. That was typically the way it went because Preston has kind of a thing that he does; what I call “slap and tickle” – the percussive, slappy left hand doing a lot of the work. It’s very rhythmic and has a certain harmonic richness to it. What I would do is basically find the spaces. I know how to find those spaces. There wasn’t a lot on that album that really started out as a melodic piece and then added Preston to it. It was the other way around. PB: ‘Stolen Glances’ from ‘Mosaic’ has that great flamenco groove. Had you been influenced by Gypsy Kings stuff? LJ: Not really. Paco De Lucia made an impression on me because I had seen him with John McLaughlin. He’s a very virtuosic flamenco guitar player. In the 1970s he made a big impression, before the whole noveau jazzmenco business kicked in with the smooth jazz scene and the Gypsy Kings. De Lucia was kind of like the top dog in flamenco. I actually took a lesson in flamenco and I couldn’t even figure out where “one” was because they have this really weird way of counting. I have friends who are very, very obsessed with flamenco, but growing up in Anglo--Saxon England, even though I have a certain kind of romance in my musical sensibility, it doesn’t quite go that far Latin. PB: You admire Lenny Brau, but what was your musical connection? LJ: The only connection is that he is one of the great jazz guitar players and I listen to a great deal of guitar playing. His specialty, in terms of the harmonics, is a very particular kind of technique; in fact the two guitar players that have really absorbed that are Tommy Emmanuel and Doyle Dykes. Both do a wonderful job translating what Lenny Brau opened up in terms of melodic artificial harmonics on the guitar. PB: You use the term “harmonic cascade” on your instructional videos. LJ: That little tinkly guitar riff that happens in ‘Love Awake’ (‘Back to the Egg’) - there’s a point where there’s a very tinkly, almost celeste-like guitar lick and that’s a harmonic cascade. That’s all within the realm of idiomatic techniques on the guitar. Those influences come from different places, and a little bit of Lenny Brau, but to be honest my primary jazz influences would be much more along the lines of Joe Pass and Wes Montgomery. PB: You’ve mentioned Django Reinhardt, as well. ‘All of Me’ could have been played in that style, but your rendition was different. LJ: It was more of a finger picking arrangement that has evolved from when I was about sixteen-years-old, when I played it for my dad in the back room of his store, and there are Django references in what I do, but again I haven’t made the kind of study of Djangology that say John Jorgenson has done – where somebody like John, who has really specialized in the Django realm, or Martin Taylor, who played with Stephen Grappelli for many years, has done, along with Ike Isaacs, who was a teacher of mine. PB: It’s surprising that you had such access growing up in England. LJ: Well, it was 12-inch vinyl records, slowed down to 16 rpm and you’d try to figure out what the guitar player was doing. We had no YouTube, no videos; none of that stuff. You had to do it with a turntable and lots of elbow grease. PB: You worked with Al Stewart on ‘Sparks of Ancient Light’. The text was loaded with historical references, so being a sound guy what was the attraction? LJ: My Al Stewart point of reference really goes back to when I was about fourteen. I had a duo and we opened for Al at a folk club in London. I was always a fan. Al was in the progressive folk niche that sat chronologically between Donovan and, let’s say, Nick Drake. Al was one of those folk guys that were on the scene and making an impression and I would listen to his records. It was cool stuff. He had been for many years associated with Peter White, who was kind of his sidekick producer and accompanist on guitar. Peter got very, very busy with his solo career in the early 1990s and they began looking for somebody to replace him. We hit it off and he came over to my studio. But first we did a short tour in Colorado. I was kind of faking it because I didn’t know most of his repertoire, but there was a chemistry that really worked. We did a demo of ‘Night Train to Munich’ that sealed a pending record deal for him, so I was hired to be his accompanist and producer. I ended up doing four albums with Al – ‘Sparks of Ancient Light’ was the last. In fact, on the 1995 record ‘Between the Wars’, ‘Night Train to Munich’ was actually credited to Al Stewart and Laurence Juber. I was actually given an artist as well as a producer credit. It was actually kind of a cool album and, also, in terms of the Django point of reference, being somewhat in that set, historically, in that period between the two world wars. Al writes historical songs. That’s his kind of genre, and I’m always interested in those kinds of perspectives. Working with Al is always some good history lessons. He doesn’t just write love songs. He writes interesting songs. In ‘Between the Wars’ there’s a great song called ‘League of Notions’ that was about the League of Nations and the Treaty of Versailles. It’s the kind of thing that they actually use as a teaching aid in schools, because it’s a great way to learn some history. That’s always kind of fun, and my job as producer was to kind of surround what he would write with kind of style-appropriate stuff – so there’s actually kind of some cool Django references on that album. But again it’s not about me being true to Django, as it is a little bit like method acting as far as getting into that space, but still playing from my perspective. So that was a fairly lengthy period of time between 1994 and about 2008, a fourteen-year period where I did some touring with Al and produced four albums. While we were doing the ‘Between the Wars’ record, I was also recording an album called ‘LJ’, my third release: the first one of mine that incorporated altered tunings. That was something of a breakthrough album for me, because it also got some worldwide exposure and I discovered audiences in Europe and in Asia. I was still doing plenty of studio work and playing for movies: ‘Pocahontas’ and ‘Good Will Hunting’. PB: It’s interesting that you’re still so committed to mentoring emerging musicians because many artists use their teaching skills to support themselves only until they can make a living as solo artists. LJ: In the process of articulating what I do, or my understanding of music, I learn from that. It’s a two-way thing with teaching. As much as the student learns, the teacher learns too. Again it’s a certain type of synergy because no two private students have the same guitarist or musical needs. But there’s also another aspect to it, which is the pro bono side to it. I do a lot of elementary and high school stuff; just really trying to give kids the idea that the guitar is a real musical instrument, and, of course, because of the way music is cut back so much in the school curriculum, which, I think, is very disappointing… The kids do better in everything if they have music appreciation. PB: I imagine these kids are really blown away when they hear you. The airwaves do not generally give us access to this kind of music. LJ: That’s true. What’s interesting is that in an elementary school assembly, they don’t know anything about Wings. They barely know anything about the Beatles, but if I say that I played on ‘The Muppet Movie’ that’s like a big thing. “Did you meet Kermit?” Whereas with the high schools, again it’s not so much those kind of credits, as: “You’ve done music with Diablo?” It’s the other side of the equation. I have this kind of musical continuum that I exist in and there are aspects to it that are about me as a composer> There are aspects to it about me as a guitarist, as a performer, as a studio musician, as an entertainer, and as a teacher; sometimes these things overlap. Not only that, but because I work with Hope, my wife, where she produces stuff and then we’ve written a number of theatre pieces together, all of these things feed into each other. It really does exist as a continuum. It’s not like the teaching is in one area and the live performances are in another area. They work together. PB: Are you working on a project with Hope, now? LJ: We’re kind of in negotiations with a musical; to try to get that into New York. It’s a ‘Gilligan’s Island’ musical and everybody sees the point of doing a ‘Gilligan’ musical in New York, but it’s a process. PB: I have two questions regarding your Beatles-based repertoire. Firstly what are the most requested Beatles-influenced arrangements and why do so many of their songs make good choices for further interpretation? LJ: First, let me preface that by saying that it wasn’t my intention to do an album, let alone two albums of Beatles arrangements. My primary goal when I launched my career wasn’t to be a finger style soloist. My primary goal was to be a composer, and my first three albums were almost exclusively original compositions. Over the years I had played the occasional Beatles song in concert, because people like that stuff and so I was getting requests from people to do albums. On my ‘Mosaic’ album, I did ‘Rain’, which was really one of the first arrangements where Hope kind of stepped into the picture and said, “You can make a tone poem out of this.” And, eventually, she said, “Even if you don’t want to do a Beatles album for anybody else, will you do it for me?” And I said, “Okay, you’re going to have to produce it,” because it wasn’t my motivation. I was still very much motivated as a composer. In fact, the previous album to my first Beatles album, ‘Altered Reality’ (Narada), was pretty much written and recorded in a space of about six weeks, although I had stuff floating around; a lot of very intense composing went into that. In terms of the Beatles repertoire, the fact is that their songs, by and large, are very, very musical and with all kinds of little twists and turns that make them compelling arrangements from a guitaristic point of view. There is, also, in terms of performance pieces, a pop culture. They are so entrenched in pop culture that doing an instrumental arrangement of a Beatles song that incorporates the stuff that people recognize from the records, whether it’s a cello line from ‘Strawberry Fields Forever’ or something that goes into all of the different pieces of ‘I am the Walrus’, the trumpet/piccolo solo in ‘Penny Lane’… That kind of stuff is built into peoples’ recognition of the song, whereas you take a song like ‘All of Me’, out of the great, American songbook, and people may know it, but they don’t necessarily associate that song with a specific iconic recording of it. There may be many, many recordings of a particular song. When I was doing my Harold Arlen record, ‘World on Six Strings’, I was listening to different versions of ‘I’ve Got the World on a String.’ There’s a Sinatra version, but there’s also a much earlier Bing Crosby version. What one associates with a particular song may be neither of those; it may be somebody else’s version. But with the Beatles, those recordings are so definitive, that they add another dimension to the arranging process that goes above or beyond simply another rendition of a standard. PB: The audience hears this song and already has certain expectations. LJ: Yeah, it is built into their pop consciousness. PB: So when you compose, what elements do you keep in mind? LJ: It could be anything. It may be a place. It may be a feeling. It may be that I wake up with a phrase in my head and I’ll pick up a guitar and start articulating it. Right now, for example, what I’m dealing with is a more thematic kind of approach. The album that I’m just starting to work on is going to be called ‘The Other Side of Midnight’, and it’s more of a late night jazz-blues record which means that there’s a certain stylistic area that it’s going to subscribe to, and it works kind of on the X rated harmony level, as far as that, in that genre, there’s a kind of noir-impressionistic kind of approach to harmony and how that all translates is quite fascinating to me and fits my particular kind of where I am creatively right now. And in this process I’ve got a new album that’s just about to be coming out, ‘Soul of Light’, which is a retrospective of a number of my original compositions. A lot of it just depends on whether it’s project related, or sometimes I just write something and I don’t know what it’s going to end up with. Other times, it will be like, with ‘Stolen Glances’, for example, my tune, ‘Guitar Noir’, where I needed an extra tune for a project. ‘Guitar Noir’ I sat down and wrote in about twenty minutes. But on my new album, I have a tune, ‘Father Time’, which took me about a year, and it didn’t really get finished until I needed it to be finished. Sometimes I’ll write something because I’ll need some particular kind of energy onstage. You just don’t know and I’ve written so many pieces. PB: How would you spend an afternoon with Django Reinhardt? LJ: I would just want to play guitar. What else would one do with Django? That would be true whether it’s Joe Pass or Wes Montgomery or any other players that are no longer with us. As a Beatle fans, I got to play directly with George, and I got to play directly or by proxy with a lot of my idols. It’s funny because I’m on this track with Seal/Jeff Beck for the Amnesty International Project, and I so wish that I’d been in the same room with Jeff… PB: Thank you, Laurence.

Band Links:-

https://www.facebook.com/Laurence-Juber-26977473886/http://www.laurencejuber.com/

https://twitter.com/OM28LJ

Have a Listen:-

Picture Gallery:-

live reviews |

|

Old Town School, Chicago, 19/5/2012 |

| Lisa Torem attends former Wings' guitarist/composer Laurence Juber's one off guitar workshop in the afternoon, and then watches him play a riveting solo concert later that night at Chicago's Old Town School. |

features |

|

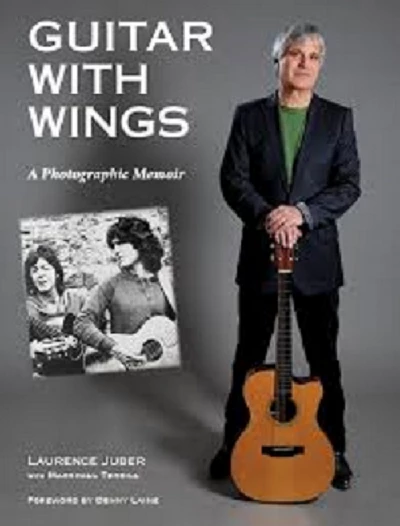

Guitar with Wings (2014) |

|

| Liss Torem looks at former Wings guitarist Laurence Juber's new photographic memoir, 'Guitar with Wings' |

soundcloud

reviews |

|

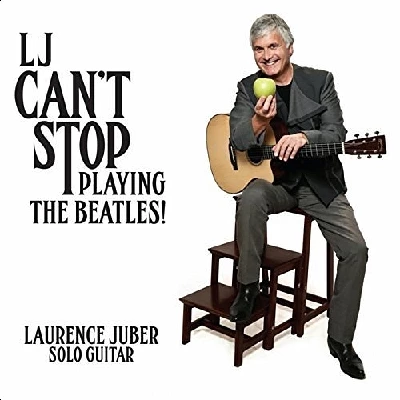

I Can’t Stop Playing the Beatles (2017) |

|

| New acoustic album from guitarist Laurence Juber which gives Beatles fans an evocative spectrum of taste and of skill |

| Soul of Light (2012) |

most viewed articles

current edition

Carl Ewens - David Bowie 1964 to 1982 On Track: Every Album, Every SongArmory Show - Interview with Richard Jobson

John McKay - Interview

Colin Blunstone - Thalia Hall, Chicago, 16/7/2025

Bathers - Photoscapes 1

Billie Eilish - O2 Arena, London, 10/7/2025

Loft - Interview

Visor Fest - Valencia, Spain, 26/9/2025...27/9/2025

Sir Tim Rice - Interview

Robert Forster - Interview

previous editions

Manic Street Preachers - (Gig of a Lifetime) Millennium Stadium, Cardiff, December 1999Heavenly - P.U.N.K. Girl EP

Beautiful South - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

Peter Perrett - In Dreams Begin Responsibilities Interview Part One

Boomtown Rats - Ten Songs That Made Me Love....

Oasis - Oasis, Earl's Court, London, 1995

Coldplay - Wembley Arena. London, 16/8/2022

Trudie Myerscough-Harris - Interview

Prolapse - Interview

Pixies - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

most viewed reviews

current edition

Davey Woodward - Mumbo in the JumboSick Man of Europe - The Sick Man of Europe

Lucy Spraggan - Other Sides of the Moon

Amy Macdonald - Is This What You've Been Waiting For?

Phew, Erika Kobayashi,, Dieter Moebius - Radium Girls

Suzanne Vega - Flying With Angels

Bush - I Beat Loneliness

Alice Cooper - The Revenge of Alice Cooper

Blueboy - 2

Cynthia Erivo - I Forgive You

Pennyblackmusic Regular Contributors

Adrian Janes

Amanda J. Window

Andrew Twambley

Anthony Dhanendran

Benjamin Howarth

Cila Warncke

Daniel Cressey

Darren Aston

Dastardly

Dave Goodwin

Denzil Watson

Dominic B. Simpson

Eoghan Lyng

Fiona Hutchings

Harry Sherriff

Helen Tipping

Jamie Rowland

John Clarkson

Julie Cruickshank

Kimberly Bright

Lisa Torem

Maarten Schiethart