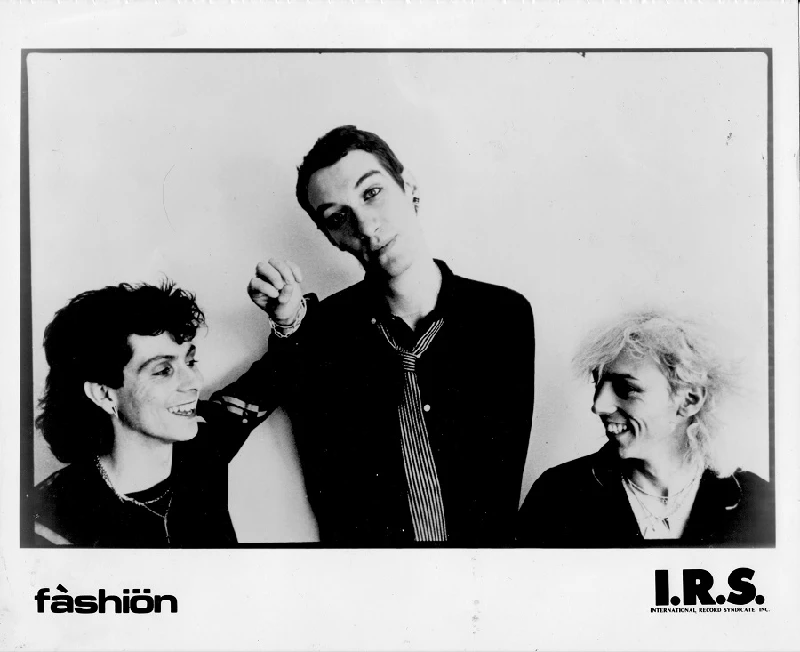

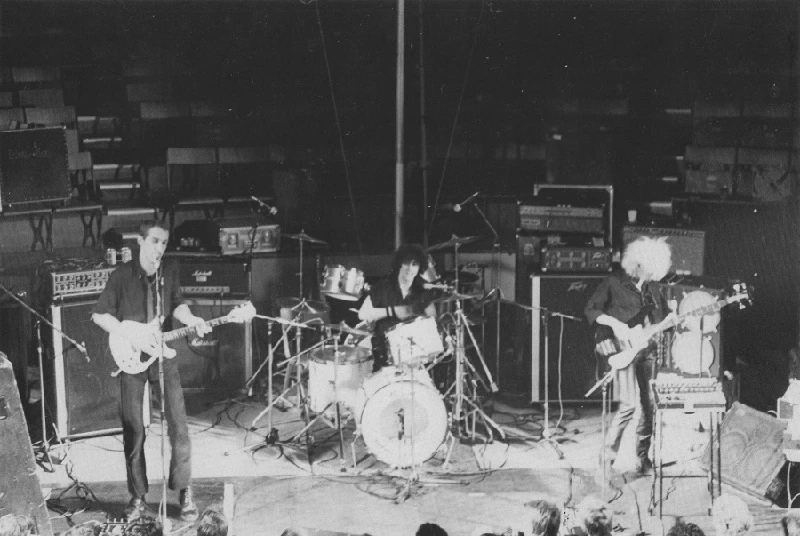

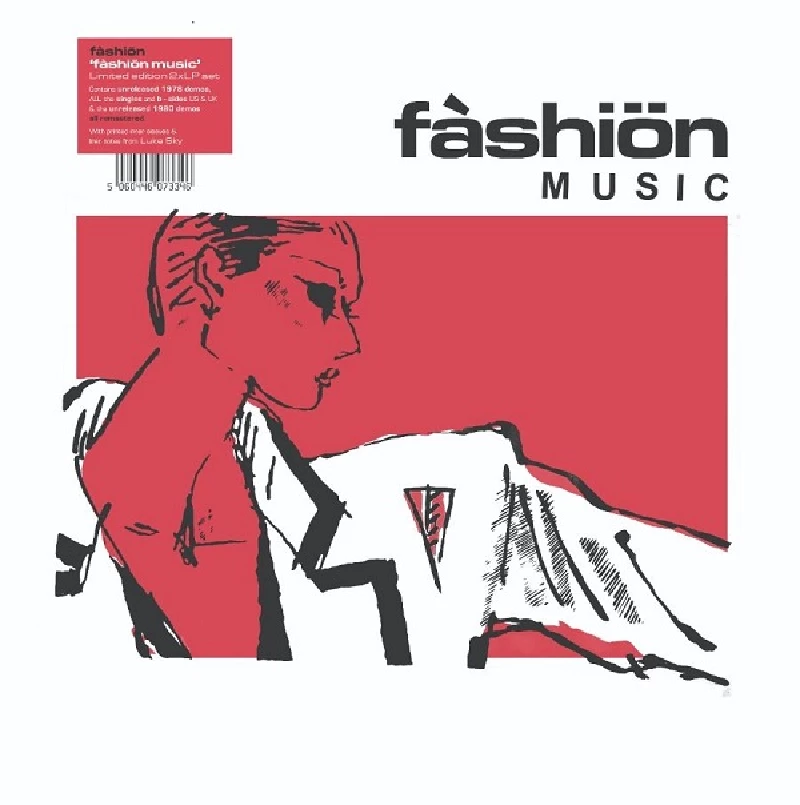

While they released three LPs with three different singers, and had a Top Ten hit with their second album ‘Fabrique’ in 1982, it is the first line-up of Birmingham-based experimental outfit of Fàshiön (or Fàshiön music as they were initially called) which is currently attracting renewed interest. That original line-up of Fàshiön, which consisted of Luke ‘Skyscaper’ James (vocals, guitar), John Mulligan (bass, synths) and Dik Davies (dums), was short-lived. lasting just two years between 1978 and 1980. A lot was, however, achieved in that brief lifetime, touring the UK with the young U2 and The B-52s, the United States with The Police, and also playing shows with the then fledgling Duran Duran as support. They also released a classic album, ‘Product Perfect’, in 1979 on their own Fàshiön music label, which combined elements of punk, reggae and electronica. A new double CD compilation, ‘fàshiön music’, has just come out on Birmingham label, Easy Action Records. It contains the three singles –‘Steady Eddie Steady’, ‘Citinite’ and ‘Silver Blades’ - that they recorded with Luke James, their B-sides, demos and alternative versions as well as their only live recording. Pennyblackmusic spoke to Luke James about his tenure as the frontman of Fàshiön and his new project This Twisted Wreckage. PB: You started out by rehearsing illegally in a derelict hotel and were so strapped for cash that your drummer Dik Davies used to use an oil drum. How did Fàshiön go from this in the space of a year to supporting The Police in the United States? LUKE JAMES: Well, Dik didn't use an actual oil drum. We "borrowed" a really beat up, old drum kit from someone's garage, just a bass drum, snare, hi-hat and a cymbal with no stand. We nailed an old bass guitar string to the ceiling and another one to the floor and strung the cymbal between them. We were all on the dole but had side jobs occasionally. For example, Dik and Mulligan used to buy cheap black plain tee-shirts from Woolworths for 50p each, razor blade slash them, stick a few safety pins in, to punk them up. Dik had an old Triumph motorbike, and they'd double up on it with a backpack crammed with tee shirts and head down the M1 from Brum to London, and sell the tee shirts at Kensington Market for ten times what they paid for them. That's where the line "two up, ton up" came from in our song ‘Bike Boys’. I had occasional midnight covert jobs for Birmingham Arts Lab Press, collating underground comics. I wrote ‘Killing Time’ while walking round a long table assembling comic pages which Fàshiön soundman Miki Cottrell hand stapled. Mulligan occasionally worked in the pub his Dad ran in Digbeth. We approached the band as a business, being one of the first bands in Brum to decide we would be our own record label. But those resources weren't enough, even though local gigs were starting to sell out. So we borrowed three hundred quid from some local gangsters and put together our first single ‘Steady Eddie Steady’, literally gluing the outer sleeve together and the labels onto the records one at a time, by hand. We had 1,000 singles, sold almost all of them at gigs and record shops in Brum, and paid back the gangsters plus interest before anyone's kneecaps went missing. We kept about fifty copies to hawk around record companies in London. None of the major labels were interested but Miles Copeland, manager of a then little-known band, The Police, and owner of Illegal Records, was interested. He financed another five thousand copies, gave us two weeks in a 16-track studio to record the ‘Product Perfect’ album, got us gigs in London opening for The Police (just as ‘Roxanne’ hit the charts) as well as London shows with The Melons, Alternative TV, The Cramps, then a UK tour opening for John Cooper Clarke and The B-52s’ first UK tour. Then he put me and the band, soundman Miki Cottrell, and manager Annette Rhodes on a plane for the first time in our lives, flew us to New York where our first gig was opening for Patti Smith at CBGBs. Then he got us a van, a list of gigs. and a map of the USA and said, "Good luck!" Skin of the teeth sometimes but we never missed a show. All the grisly details are in my book ‘Stairway to Nowhere’, available at Lulu.com PB: The Birmingham post-punk/indie scene of the late 70s/early 80s is now being recognised latterly as having produced some really great music, and Easy Action Records, which has released ‘fàshiön music’, has done much to promote this. How conscious were you at the time that it was such a remarkable scene and how much of an influence did that local scene have on Fàshiön music? LJ: It usually takes a while for things to travel the 120 miles from London to Birmingham, and they usually get perverted on the way! So when punk hit Brum we embraced it into a culture already strongly influenced by reggae, experimentation, and the burning desire to get the fuck out of Birmingham and see what the rest of the world looked like. At least Fàshiön music did! But there were so many great bands (who mostly seemed to hate each other) vying for that passport! So, there was a combination of innovation, competition, and a massive musical swell of people putting bands together that were different. We were one of the first, but in short order came UB40, The Prefects then Dexy's, The Ravens, Dansette Damage, TV Eye, Neon Hearts, The Beat and a host of others until eventually, after several line-ups as an art band, there was Duran Duran. So, we were inspired and challenged all at the same time. We really did feel we were doing something different. We were the future of no future, we were! Armed with more front than Southend, we fully intended to conquer the world! PB: You toured with the young U2 and Duran Duran were a regular support to you. Did either of them seem destined to become the stadium acts they developed into when you worked with them? LJ: We knew the managers of Duran Duran, the owners of the Rum Runner club. We used to rehearse at the club when they were putting Duran Duran together. Seriously, I was once asked by their managers if I thought Simon Le Bon could sing (reply unprintable!). We knew money was being poured into them. For example, one afternoon a whole brand new back line and PA system turned up in the room at the Rum Runner where they rehearsed. It was guarded by a very large gentleman in a black suit who did not appreciate our drummer Dik Davis's crack about there being a music shop in town somewhere with a large hole in its back wall. We were told not to go anywhere near the new equipment. I think their plan was to transform Duran from an art band into Birmingham's darlings of the New Romantics. They had talent, they had the right musicians when Le Bon and Andy Taylor joined, and they had the right people managing them. So yes, I was pretty sure they would succeed commercially. This was right around the same time, in 1980, when I was pretty sure that Fàshiön music would not! But then our initial aim had been to succeed by being different. We didn't want to write three minute radio length songs, and we didn't want to do intro/verse/chorus/verse/chorus/middle 8/chorus chorus format songs. When Copeland asked us for a more commercial follow-up single to ‘Steady Eddie Steady’ we gave him ‘Citinite’! There's another reference to this in the song ‘Bike Boys‘ – “vinyl suicide, and it goes like this.” We deliberately committed vinyl single suicide, and today that song is sometimes still hailed as something special by a faithful few. We wanted to succeed artistically and commercially by breaking the rules. We had no intention of being puppets on a promo budget string eee-oh- eee-ohing our way up the charts. U2 were another kettle of spanners though. In that early pre-Island Records time they blew the roof off night after night at every gig on that tour, whether it was thirty people or three hundred. They had a massively powerful sound and were all really nice young men dedicated to just one thing - their band. Some nights Fàshiön music would open for U2 on that tour, other nights U2 would open for us. There was none of the snide rivalry that I was all too used to and felt all too used up by. They were as fresh and exciting as I felt Fàshiön music was becoming exhausted and jaded. PB: In ‘Killing Time’ you sIng, “I’m just killing time/I want what is mine.” How political a band was Fashion? LJ: We were a very political and socially aware band, as anyone who listened to or read the lyrics could tell. ‘Product Perfect’ - anti-commercial consumerism ‘Burning Down’ - mental health ‘Red Green and Gold’ - racial equality. ‘Bike Boys’ - sexual equality ‘Don't Touch Me’ - alienation ‘Technofascist’- totalitarian government by technology (sound familiar?) In fact I wrote ‘Technofascist’ forty-three years ago. Last week with my new band, This Twisted Wreckage, we finished recording a new song called ‘Techno Savage’. The struggle for liberty continues - and political consciousness, owning up to how fucked up the world is, and how the solutions lie within all of us, within our collective grasp. So, yes, forty-two years after I was in a political band you could dance to, after a long spell in the commercial wilderness just being a musician (and not a fame junkie), I find myself in This Twisted Wreckage, a socio-political band you can also dance to. Talk about circles! (just not the ones under my eyes please!) PB: The first line-up of Fàshiön -and the one in which you were involved- was very short-lived, lasting barely two years. You were doing something radically different, incorporating electronica, punk and reggae in the same song. It is often said that groups that break the mould and new ground, such, as for example, The Sex Pistols and Joy Division, by nature turn to burn out quickly. Was that the case with Fàshiön? Why did you leave in 1980? LJ: I think this is a fair enough observation. When you go against the grain, when you push to do something different, the obstacles you encounter in the established way of doing things are huge and exhausting. I mean, not to in any way draw a parallel musically, but the first time people heard Tchaikovsky's music performed based on what they were used to hearing they thought it was dissonant garbage. We were often asked what kind of a band we were. To which we could only answer "We're this kind of a band. Listen to us!" We were often asked what do you sound like, and what else could we reply other than “Well, we sound like this!” But there comes a point where trying to do something different and going against the status quo you either buckle, give in and do like they tell you to, or you walk away. There are some brave stoic souls that refuse to quit, I'm thinking of people like Mark E Smith. But personally having been very close to the machinery of celebrity and fame and seen what it does to people, how it changes people usually for the worst, (and a good number of those people weren't such great people to start with), I realised I was more interested in being a musician than I was in being a fame junkie. It was a very difficult decision, and one that I've since acknowledged to my former bandmates was somewhat unfair to them. To just walk away, feeling like I was being unheard by everyone including my own band, with everyone clamouring for us to do something more commercial, to have a hit record. I had nowhere to live, I had no friends - I just knew people. There was no-one I could trust, there was no one I could love. I’m the circus I felt trapped inside. Obviously there has been a degree of questioning whether I did the right thing, but I've played in every kind of unknown band you can think of, I've played reggae, I've played blues, I've played my original music, I've studied Flamenco guitar, I've played in unknown bands in San Francisco, in Charlottesville Virginia, in London, in Bordeaux, in San Lorenzo, and I've met some amazing musicians. And if you think about it, the world is filled with great musicians, but not all of them are interested in becoming famous, but most of them are interested in one thing - playing music. PB: You had achieved a lot in a short time together. Do you regret that it ended when it did? LJ: No, I don't regret the way it ended, I think it was the right decision for me and quite possibly for the other people involved, although I'd be lying if I said I was thinking about them at the time. I was very much thinking about my own well-being and what I wanted to do. And in the long run I have no regrets about any of the mistakes that I've made in the past, because each and every one of those mistakes are stupid decisions that along the way has led me to live in a place I love, married to my soulmate, with two amazing teenage children, and now, quite surprisingly, to find myself playing in a band, This Twisted Wreckage, that I consider to be the best music I've ever been involved in creating. Refusing to quit playing music, not giving in, and somehow coming through recent major illnesses, to just stay alive and not quit seems to pay off artistically. At least for me. And to be honest, whereas it would be nice if This Twisted Wreckage was commercially successful, I seriously doubt that I'm going to, or would want to, suddenly become a star at the age of 70. But I am intensely proud of the music that we're producing. It is one of the great joys of my life. I'm so fortunate to have the musical and magical chemistry that I have with my bandmate Ricky Humphrey. PB: ‘Product Perfect’, as does all of Fàshiön's music, has a really fresh quality because it is difficult to slot it into a category. Do you have any plans to re-release it? LJ: Yes. Funnily enough the quarter-inch studio mixdown tapes were found just a few years ago by producer Miki Cottrell's son Daniel in a cupboard under the stairs at their house. The tapes of the original mixes were digitally transferred at Brian Mostyn’s studio (manager of The Beat and Fine Young Cannibals). A limited green vinyl release came out on Modern Harmonic and Cherry Red Records a couple of years ago. And following on the Easy Action Records vinyl and CD releases of the Fàshiön music demos, singles, and only known live recording with ‘fàshiön music’, EAR will be putting the original album of the studio mixes of ‘Product Perfect’ out on CD later this year. PB: How did you and Ricky Humphrey first become involved with each other in This Twisted Wreckage? LJ: I first heard Ricky Humphrey's music about three years ago when I came across a band called Ishkah. I was heavily into bands like Thievery Corporation at the time and I really liked Ishkah's music. So I followed them on Bandcamp, bought the EP, and at some point had an email communication with Ricky. We talked back and forth for awhile, and eventually I asked him if he would be interested in sending me a piece of music to see if I could put some vocals on it. The day after he sent me the first piece of music, which was two years ago now, I learned that a close friend of mine had taken his own life. I was kind of in shock and very distraught, so I did what I always do when I'm in a bad place and I turn to music. I brought up Ricky's piece of music, armed a microphone and right off the top of my head came up with a song called ‘Forgotten Summer’ in memory of my lost friend. I thought it was just one of those things caused by the situation, but when Ricky sent me the second piece of music, as I was listening to it for the very first time, lyrics and melody lines started to appear in my head. And to be honest it's been that way now for 2 years, and we've written, recorded, and produced 85 songs. Ricky lives in the south of England, and for the last 34 years I've lived in Northern California, so other than through Zoom meetings, emails and texts and file exchanges Ricky and I have never met in person. Yet. We plan to do so next year to record together in a studio. The plan is to put together a live band. This is an example of technology not alienating but joining two musicians. Ricky has also been through the machinations of the music business, and we have both learned to sublimate our egos for the common good of the music, for each song that we're working on. This has made communication not only easier but as we've progressed sometimes seemingly telepathic, which is handy for any time the wi-fi is down! What is central to This Twisted Wreckage is its own version of what was central to the original line-up of Fàshiön music, which is the sheer exuberant joy of the creation of music that sounds fresh, different, and exhilarating. As I said earlier in this interview, things move in circles. The spiral is more common in nature than a straight line, which in fact practically never exists in the natural world. So I do find myself extremely pleasantly surprised and incredibly motivated and inspired to be fronting at this stage of my life what feels like the best band I've ever been in. PB: This Twisted Wreckage have recently released their debut EP digitally on Bandcamp. How do you intend to promote it? What are your plans for the rest of the year? LJ: We have released into the digital world a three song EP, ‘Dancing With Angels/ Always Arriving/ We're All Gifted’, and the links to stream download or purchase those songs as well as a video for each of those songs can be found on our website . About six months ago, we had an addition to the team that we now call This Twisted Wreckage Productions, with Pete King (former manager of internationally successful reggae band Steel Pulse) joining us as production consultant and pathfinder. Since then there has been some interest shown in the band by BBC Radio DJs and we're hoping that soon we might get some airplay. But, and I can't emphasise this enough, whereas Ricky and I would only be too happy at this stage in our lives to become financially secure - you know lying in hammocks somewhere in the Bahamas sipping alcohol-free cocktails - such pipe dreams are only secondary considerations. The almost magical, alchemical, joyful creation of This Twisted Wreckage's music is, and always will be for me and Ricky the most important thing about this band. It's one of the reasons why I believe that this is the best band I've ever been in. The other reason being when I stop to listen back to what we've created. It's kind of hard to believe that we've created such a diverse and prolific body of work in such a relatively short space of time. Moving forward the wreckage might well be twisted, but there will always be hope of great things emerging from the rubble, dancing out under the sun, shaking a defiant fist in the faces of dictators and oligarchs! Can you imagine how amazing it feels to be this enthusiastic about and engaged with life and music, after having been kicked around by it for seventy years? Well I can! PB: Thank you.

Band Links:-

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fashion_(band)https://www.lulu.com/shop/luke-james/stairway-to-nowhere/paperback/pro

www.this-twisted-wreckage.com

https://www.facebook.com/ThisTwistedWreckage/

Play in YouTube:-

Picture Gallery:-

intro

Luke ‘Skyscraper’ James, the original frontman with Birmingham post-punk outfit Fàshiön, speaks to John Clarkson about his tenure with the band, their new compilation ‘fàshiön music’ and his current band This Twisted Wreckage.

most viewed articles

current edition

Carl Ewens - David Bowie 1964 to 1982 On Track: Every Album, Every SongJohn McKay - Interview

Editorial - July 2025

Billie Eilish - O2 Arena, London, 10/7/2025

Visor Fest - Valencia, Spain, 26/9/2025...27/9/2025

Hothouse Flowers - Photoscapes

Bathers - Photoscapes 2

Bathers - Photoscapes 1

Cleo Laine - 1927-2025

Loft - Interview

previous editions

Heavenly - P.U.N.K. Girl EPBeautiful South - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

Trudie Myerscough-Harris - Interview

Pixies - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

Boomtown Rats - Ten Songs That Made Me Love....

Fall - Hex Enduction Hour

Sam Brown - Interview Part 2

Doris Brendel - Interview

Blues and Gospel Train - Manchester, 7th May 1964

Donovan - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

most viewed reviews

current edition

Sick Man of Europe - The Sick Man of EuropeAmy Macdonald - Is This What You've Been Waiting For?

Phew, Erika Kobayashi,, Dieter Moebius - Radium Girls

Alice Cooper - The Revenge of Alice Cooper

Blueboy - 2

Lucy Spraggan - Other Sides of the Moon

Cynthia Erivo - I Forgive You

Davey Woodward - Mumbo in the Jumbo

Philip Jeays - Victoria

Bush - I Beat Loneliness

Pennyblackmusic Regular Contributors

Adrian Janes

Amanda J. Window

Andrew Twambley

Anthony Dhanendran

Benjamin Howarth

Cila Warncke

Daniel Cressey

Darren Aston

Dastardly

Dave Goodwin

Denzil Watson

Dominic B. Simpson

Eoghan Lyng

Fiona Hutchings

Harry Sherriff

Helen Tipping

Jamie Rowland

John Clarkson

Julie Cruickshank

Kimberly Bright

Lisa Torem

Maarten Schiethart