Pere Ubu - Interview

by Mark Rowland

published: 6 / 12 / 2012

intro

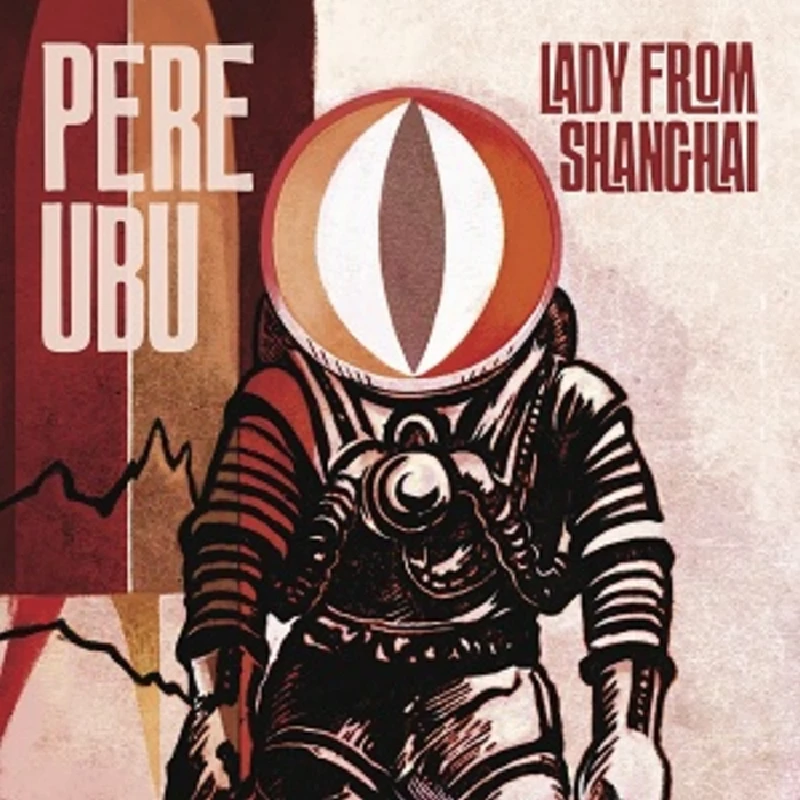

Mark Rowland talks to David Thomas, the front man with influential alternative rock act Pere Ubu, about his band’s new ‘dance’-influenced album, ‘The Lady From Shanghai'

“I’m no expert on dance. I think it’s a disaster. I mean, if you want to look at what’s destroyed music as a creative force, you should look at dance. Nothing’s happened since 1990. Well, that’s an exaggeration, of course there’s pockets of things that have happened, but substantively not – black culture is bankrupt, white culture is scared and cringing in the corner, and it’s all basically down to dance.” So says David Thomas, the front man of Pere Ubu, who are just about to release a dance album, ‘The Lady From Shanghai’. Well, the band call it a dance album, but it’s more like deconstructed dance, as if the band smashed ‘dance music’ to pieces and put it back together with sticky tape, without checking which bits went where. The music is more electronic than the band has ever been, and although it’s fairly tightly wound, as you would expect a Pere Ubu album to be, it feels like the band has loosened the screws a little. It’s certainly avant-garde, but the songs maintain a distinct pop sensibility, albeit some distance away from the sort of stuff that troubles the charts. “As I said, I’m no expert on the damn thing, but I suppose there’s a certain amount of deconstructing of the elements, if you want to use these fancy terms,” Thomas says. “I’m sure my notion of dance goes back to the early 80s or something, and that’s really where we started this quote unquote deconstruction process, basically because I was using an emulation of the Korg M20s, which was pretty much the standard machine for that era. So yeah, I wouldn’t use that term of deconstruction, but we definitely make use of the elements and try to, uh, I don’t know if subvert is the right phrase, but the only dancing that’s really possible with it is really goofball dancing. It would force your body to do things on the dancefloor that the girls would not like, would not be attracted to, so that was certainly on my mind.” To create dance music that it’s almost impossible to dance to? “Yeah. One of our superfans who had an advance copy just points out that really the intention seems to be to subvert anything your body means to do and turn it all internal. There’s a huge amount of detailing on the record. If you follow any one strand of some sound, the thing takes on a different perspective and different look to it. That was something I spent many months working on, the detailing of it.” Thomas’ apparent irritation with dance music should, of course, be taken with a pinch of salt. If he has a genuine problem with anything, it is the way in which pop music has become referential, rehashing old ideas. “It’s one of those things that I really hate to talk about too much, because you just sound like an old fart. But one thing that’s really evident, and I pick on 1990 as just a date, it’s not written in stone, is that fashions in music used to cycle through pretty damn quick. In the 1960s, three years, two years was a really long time and whatever fashion or style of music really didn’t last much longer than that. Stuff was coming or going quicker than you could spit at it. Now, if you just look around, the TV weatherman is doing hip hop, your grandpa is doing hip hop. What kind of world is this? When your grandpa, when your parents have their baseball caps on sideways? You think they’d be able to come up with something other than a damn baseball cap on sideways, which was a cliché 20 years ago and it’s still a cliché. So I was just sort of getting mad about the whole thing.” So is it perhaps the absence of danger, of controversy, in pop music today? Since the 1950s, pop and rock was synonymous with rebellion, a way in which teenagers could annoy and outrage their parents, give themselves an identity. Now youth identity is a pastiche of those of previous generations, both in fashion and music, and parents are also likely to embrace the new, which isn’t a million miles away from what they have listened to before. “What you have is basically just fear,” says Thomas. “It’s a fear of in any way standing out from anything. The main fear is a massive, paralysing fear of saying something that someone might take offence to or disagree with. I mean gee, what a terrible monster you must be if you say something that somebody takes offence at. Gee whiz! I find that distressing. And of course, dance promotes that attitude because there are no words in dance. That’s another exaggeration, but effectively yes; there are no words. What words there are, are meaningless. And by dance, I now extend it out to anything you’d see in pop music. They’re all the same route. The fear is paralysing everybody into not saying a damn thing. And I’m not talking about supposedly ‘controversial’ things; that’s baloney.” As he rants, Thomas’ voice gradually loses its irritable energy fading out into a tired sigh: “I don’t like sounding like an old poot. But I mean, you know, I am an old poot. What the hell do I care? I’m free now. Nobody’s going to like what I do, and I don’t have to do anything, so what the hell does it matter.” His entertaining bolshiness returns as he attempts to explain his current view of the world. “You get into this Clint Eastwood mindset, of – what was that movie? The one about the car.” Gran Torino? “Gran Torino, yeah. You get into that mindset of wanting to go out and say things that offend somebody just for the sake of it. I look forward to the day I say something that offends somebody so that I can refuse to apologise for offending them. That’s not a good mindset. That’s really a sidetracking sort of thing. I’ve got better stuff to do than looking forward to the day I offend someone so I can say: ‘I’m not apologising’. I’ve got meals to cook. I’ve got to sweep the floor. I’ve got stuff to do.” His words are timely, with more and more instances of people being arrested for their offensive comments; for example, Matthew Woods, who made offensive jokes on his Facebook page about April Jones while the story of her disappearance played out in the newspapers, or Barry Thew, who made his own T-shirt celebrating the deaths of two police officers in Manchester. Though clearly not nice people, there has been some debate as to whether these people should be arrested for their insensitivity. There is no question as to what camp Thomas is in. “I can’t believe this. Why people aren’t outraged that the police get involved because you’ve said something offensive? It makes you despair.” Thomas’ argument is simple: you can’t arrest someone for being an idiot: “And I don’t want to defend somebody for being an idiot, but you know, hell, that’s my taxpayer money that’s going to waste by bothering to arrest somebody because they’re offensive. Gee whiz.” Freedom of expression is a hot topic in media at the moment, predominantly due to the fact that, in the wake of the Leveson inquiry, the press themselves believe their freedom is threatened if their regulatory body was underpinned by statute. Thomas is less animated about press freedom, but he feels that the solution to the problem is simple: “With this whole hacker thing, you don’t need a whole bunch of new laws. You just enforce the laws you got. There are plenty of laws that can apply to this. Why we have to have a whole other tranch of unelected prunes because of this issue, I don’t know. Why can’t we just enforce the law and put somebody in prison? There’s a radical idea for you.” The band has described ‘The Lady From Shanghai’ as a radical idea, that “marks a new era of the history of Pere Ubu. In some ways, it is shocking.” But Thomas has been toying with electronics and synthesizers for some time, now, whether with Ubu or with side projects such as David Thomas and Two Pale Boys. Is Thomas using synthesizers because they’re fun to play around with? “Obviously they’re fun to play with, but it’s hard to build an entire career on the whole notion, the premise that it’s fun to play with. I wanted to do something that involved a lot more synthesizers,” he chuckles, which, for an allegedly surly man, he does often. “There are a number of trends that are going on that are interesting in the realm of computer music, where you’re running some jpeg through some sequencer that turns it into random sound, all that sort of stuff, which on it’s own, and separated from reality, is really kind of dire.” The problem, he explains, is the lack of connection between the artist and the listener, the tendency for distance and coldness in electronic music. There has to be a human connect at some point, he explains, and you have to put it into a context of real emotion and real life and saying something. “I like all that stuff in a really platonic way, but when you go see it, it’s ‘Eh alright, fine.’ So I was interested in it and Keith Moliné (Pere Ubu’s guitar player-Ed) is rabid about that tuff and always has been. It’s interesting to use the techniques musically, instead of a laptop performance or something, which I would go to, but like I said, I’d come out of it going: ‘Eh, alright, fine’.” It was important, says Thomas, to give the process an element of danger (“and I use the word ‘danger’ in the loose, crappy way that it’s used these days.”). He cites the drums as an example. None of the songs, according to Thomas, make rhythmic sense. That is not obvious to the casual listener, but it would be a hell of a job for a drummer to learn to play them. “You don’t sit there and go: ‘they dropped a beat and a half!’ or ‘there’s a measure missing there!’ and that stuff’s all over the place. I think there’s one song that makes sense, if you had to sit there and chart it out, like a drummer would have to do, if you were learning the damn thing. But again, there’s not big, neon signs pointing at it. I really went to town on the sort of organic sense of time stuff that I’ve been working on for quite a while, now.” A lot of these ideas are explored in ‘Chinese Whispers’, a hundred-page book of what Thomas calls liner notes – the story of how the album was made, the methods and thinking behind every song, the recording process, the title, even the choice of artwork. “I figured: well, nobody’s done a hundred-page liner notes to an album before, so I’m going to do it, damn it. Just because it’s there. In it, I describe the methodology for this record, which was Chinese whispers, where no two musicians were ever in the same room – I don’t count myself as a musician, I’m the producer.” Thomas stuck to this rule religiously – throughout the writing and recording, no member of the band played together. “There was one time that any two were in the same room at the same time, and that was for 37 seconds,” says Thomas. “I counted it, and I got them out of there as quickly as possible. No two people were ever together in the recording of this.” During the writing process, all the band members would pass Thomas ideas for songs. Thomas would work on them and pass on the ones that were clicking to another member of the band. They would add some new ideas and pass it back and so on, until the band had put into the song. “It’s a very complex system, which is why it takes a hundred pages to explain it all, but in the end I wanted to remove composition from the provenance of rehearsal.” In a way, this brings an element of improvisation to the recording by removing the unsaid communication between musicians. ¬ “Clearly for a long time, I’ve been exploring the problems of improvisation and how to get improvisation to work in a human way, as opposed to a plinky-plonk ‘Oh Jesus, Ok. The bus is coming soon,’ sort of way. So this album is essentially improvised. Now you have to go a round about way to achieve that when you’re working with a traditional band, but I went round about, and it’s been achieved. Nobody knew what anybody else was doing, and when it came time for performance of your part in the composition of the song it was done live in one take, two takes, and generally I would lie to the musicians about what they were supposed to do and mislead them, move the goalposts at the last minute, so they were always uncertain but determined.” “It’s rather complex how I went about it, but that was the intention. I’ve been moving towards this with Pere Ubu for quite a while. It’s quite an accomplished band now, capable of this sort of activity, where it’s just: well what the hell, let’s just do it. They’re all disciplined and creative.” That method must require a lot of mutual trust in order to pull off. Thomas chuckles again. “They don’t have any say in the matter, you know. They’ve just got to trust me. And to their credit they generally do. When you work with people who are exceptional, you want them to be exceptional, and basically you trust them.” When Keith Moliné gave Thomas the closing track ‘Carpenter’s Son’, it was basically a laptop guitar track. Thomas’ reaction to the track was: “Oh god, what the hell am I going to do with this thing?” After studying the piece for a long time, he decided to trust Moliné. “Eventually, I realised that it was just a 12-bar blues without any bars, so then I had to weigh in and offload from that. Michele (Temple-bass, Ed) presented this demo on which nothing happened. It was this short little musical thing, but then it was just three or four minutes of this synth bell thing, and she just hadn’t bothered to cut it off. She was working on the front part, and she had laid that long bells thing on there just to work across until she was done. She submitted it to me and I thought, ‘Well, we’re going to keep the bell.’” All of this, including the album’s running order, is included in ‘Chinese Whispers’. Every time he starts talking about an element of the recording, Thomas mentions the book. He laughs at the idea of it. “Everything about this is covered in a chapter of the hundred-page liner notes. It really is a magnificent achievement. I’ve worked longer on that than I did on the record. Well, not really, but it seems like it. Yeah, I cover that issue in a chapter. I cover the artwork, the connection to the Orson Welles thing.I describe the Chinese whispers. Then there’s a long essay called ‘Drums and the Modern Man’, which analyses the evolution of drums, which was part of a longer piece that I abandoned, which was involved with the significance of signal compression ratios on FM radio in the 1970s, and what that did to drums, and the change in the vocabulary of drums because of that. I was never going to finish that, so it’s in there and a bunch of other stuff, I can’t remember, some other crap. A hundred pages.” ‘Long’ is certainly a key adjective when it comes to ‘The Lady From Shanghai’, with the album’s long gestation period and the book-size liner notes, to the length of the tracks themselves. Everything about the record has been painstakingly constructed. It is also diverse, with overtly electronic tracks alongside those that are closer to Ubu’s avant-garage sound. Tracks such as ‘Musicians are Scum’ are indeed rhythmically strange, with drum parts that work in a way completely contrary to normal expectations. Others, such as the drums on ‘Free White’ sound almost like 4/4 disco rhythms, but closer listening reveals something off about them that you cannot quite put your finger on. It’s a fantastic record, one of the band’s best of recent times, and one of the first notable releases of 2013, thanks to the challenge Thomas set himself and his bandmates. “I’ve decided, by the way, that the next record is going to be all two-minute songs,” Thomas lets out a long chuckle. “Two-minute singles. What the hell else am I going to do?”

Band Links:-

http://www.ubuprojex.com/https://en-gb.facebook.com/official.ubu/

https://twitter.com/ubuprojex

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pere_Ubu

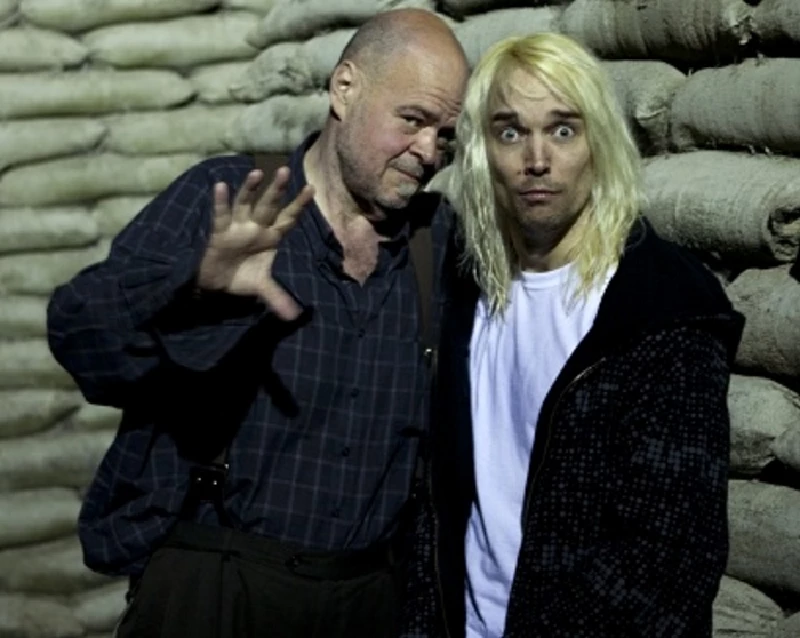

Picture Gallery:-

interviews |

|

Interview (2017) |

|

| Erick Mertz talks to David Thomas, the front man with influential alternative rock act Pere Ubu, about his group's experimental new album, ‘20 Years in a Montana Missile Silo’. |

| Interview (2009) |

| Interview (2008) |

| Interview with David Thomas (2006) |

| Interview with David Thomas (2005) |

| Interview with David Thomas (2004) |

| Interview (2004) |

profiles |

|

A Self-Indulgent Reflection on David Thomas (2025) |

|

| Mark Rowland reflects on four interviews with Pere Ubu’s notoriously cranky frontman David Thomas, who died in April. |

live reviews |

|

Musician, Leicester, 12/11/2014 |

|

| Dave Goodwin at the Musician in Leicester watches Peru Ubu play a confrontational yet brilliant double set of experimental rock |

| Blackheath Halls, London, 27/2/2010 |

| Islington Academy, London, 18/9/2005 |

favourite album |

|

The Modern Dance (2006) |

|

| For our 'Re : View' slot, in which we look back on old albums, Mark Rowland writes about Pere Ubu's 1976 classic debut album 'The Modern Dance', which has recently been reisssued |

| Dub Housing (2002) |

reviews |

|

Lady From Shanghai (2013) |

|

| Complex, but compelling fourteenth album from Cleveland avant-garde rockers, Pere Ubu |

| Long Live Pere Ubu (2009) |

| Why I Hate Women (2006) |

| St Arkansas (2005) |

most viewed articles

current edition

Carl Ewens - David Bowie 1964 to 1982 On Track: Every Album, Every SongArmory Show - Interview with Richard Jobson

John McKay - Interview

Colin Blunstone - Thalia Hall, Chicago, 16/7/2025

Bathers - Photoscapes 1

Billie Eilish - O2 Arena, London, 10/7/2025

Loft - Interview

Visor Fest - Valencia, Spain, 26/9/2025...27/9/2025

Sir Tim Rice - Interview

Robert Forster - Interview

previous editions

Manic Street Preachers - (Gig of a Lifetime) Millennium Stadium, Cardiff, December 1999Heavenly - P.U.N.K. Girl EP

Beautiful South - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

Oasis - Oasis, Earl's Court, London, 1995

Peter Perrett - In Dreams Begin Responsibilities Interview Part One

Boomtown Rats - Ten Songs That Made Me Love....

Coldplay - Wembley Arena. London, 16/8/2022

Prolapse - Interview

Pixies - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

Trudie Myerscough-Harris - Interview

most viewed reviews

current edition

Davey Woodward - Mumbo in the JumboSick Man of Europe - The Sick Man of Europe

Lucy Spraggan - Other Sides of the Moon

Amy Macdonald - Is This What You've Been Waiting For?

Phew, Erika Kobayashi,, Dieter Moebius - Radium Girls

Suzanne Vega - Flying With Angels

Bush - I Beat Loneliness

Alice Cooper - The Revenge of Alice Cooper

Cynthia Erivo - I Forgive You

Blueboy - 2

Pennyblackmusic Regular Contributors

Adrian Janes

Amanda J. Window

Andrew Twambley

Anthony Dhanendran

Benjamin Howarth

Cila Warncke

Daniel Cressey

Darren Aston

Dastardly

Dave Goodwin

Denzil Watson

Dominic B. Simpson

Eoghan Lyng

Fiona Hutchings

Harry Sherriff

Helen Tipping

Jamie Rowland

John Clarkson

Julie Cruickshank

Kimberly Bright

Lisa Torem

Maarten Schiethart