Stewart Copeland - Interview

by Lisa Torem

published: 14 / 11 / 2014

intro

Lisa Torem chats to former Police drummer Stewart Copeland about his solo career and composing for film and television

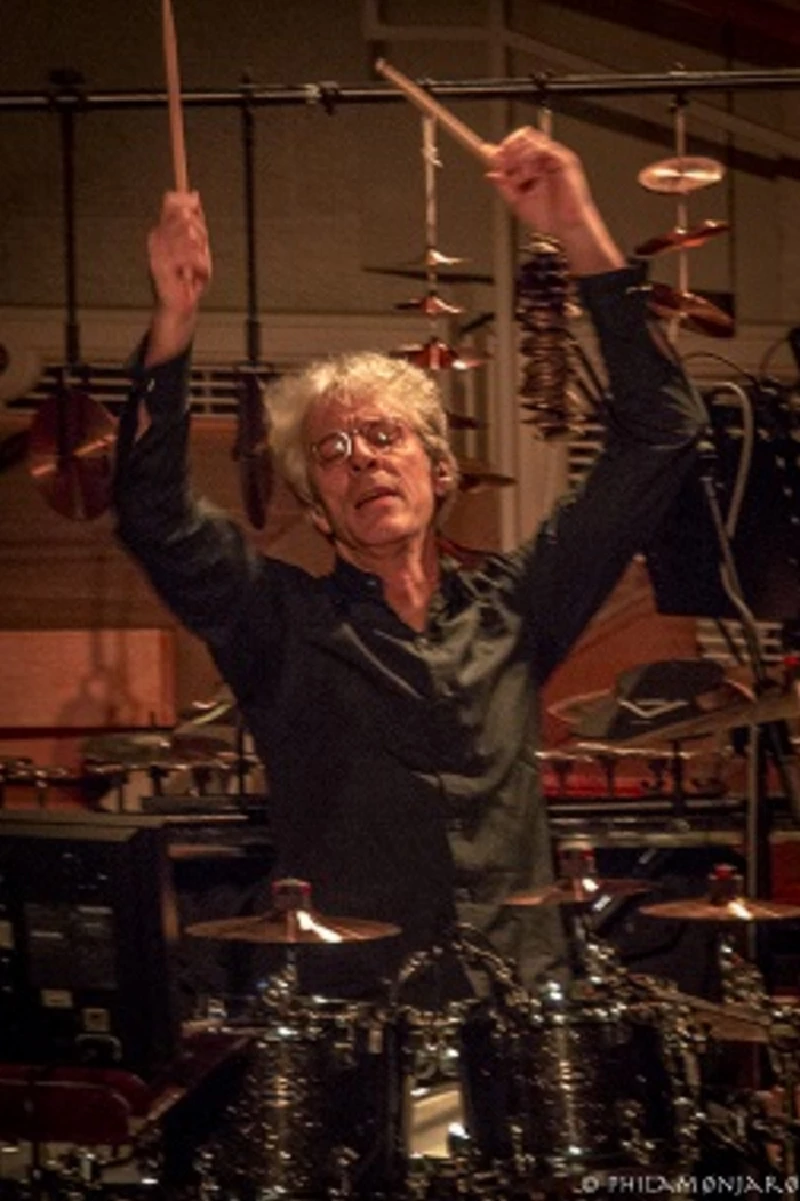

Watching Stewart Copeland perform with the Chicago Symphony is exciting but surreal. His co-stars include octopads, a glockenspiel and, oh, a sixty-piece orchestra. Overhead is the 1925 silent film ‘Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ’, which Copeland has edited. The audience watches as excitable Judah Ben-Hur reunites with an old friend who has since become a Roman soldier. Their peaceful reunion doesn’t last long; a series of dramatic twists occur, which are echoed by powerful melodies and daring textures. There are people in the audience who sit stunned. Is this the rock/punk drummer of The Police? Is this the author of ‘Strange Things Happen: A life with The Police, Polo and Pygmies’? Stewart Copeland has undergone many incarnations; more than most of us will ever experience, but it’s pretty cool to ride shotgun. As Copeland once stated, “The thrill of a great show is a two-way current that energises an audience but positively electrifies the performers.” Though he said this after performing in Italy, the same vibe applies here. Copeland may be best known for forming the Police in the late 1970s. With Andy Summers and Sting, he spent eight years as the aggressive, expressive drummer that crystallized many of their hits. During their time together, he had the foresight to take over fifty hours of footage. The film depicted the rise of the Police and the reactions of fans. ‘Everyone Stares: The Police Inside Out’ would receive glowing reviews at the 2006 Sundance Festival. The group disbanded in 1984, but by that time Copeland had already begun a serious career as a film composer. He went for the top. Francis Ford Coppola directed his first assignment, ‘Rumble Fish’. Copeland was a novice but quickly learned the lingo. He would learn how to create a “happy/sad” moment. He would go on to score ‘Wall Street’ ,and too many other TV shows and films to mention. Ever curious about non-standard ways to instigate complex rhythms, Copeland visited Africa. Working with local percussionists, he completed ‘The Rhythmatist’ in 1985. Towards the end of that decade, he formed Animal Logic with Stanley Clarke, and in 2000 he collaborated with bassist Les Claypool and Trey Anastasia (Phish) to form Oysterhead. Had it not been for an accident, he might have spent a more leisurely time with Manzarek-Krieger. In 2007, he joined Summers and Sting for a Police reunion. “I get to be the original guy,” he said, recalling what made that time special. Copeland went on to tour with longtime friend Clarke in Paris and Rome in 2012. As far as scoring and arranging, Copeland is intrepid and exploratory. He makes setting sophisticated stories to music sound easy. At a recent Q & A before his Chicago debut of ‘Ben-Hur’, he referred to scores as “dots on pages.” He makes you think anyone can write lush, cerebral passages for strings and trumpet cacophonies that rival rush hour gridlock. He shrugs his shoulders at the suggestion that his precise timing is anything but intuitive. Yet he shuttles from gamelan melodies to reggae rhythms without ceremony. He has performed with D’Drum and the Dallas Symphony Orchestra, written a percussion concerto earlier this year for the Liverpool Philharmonic, set, to haunting music, Edgar Allan Poe’s ‘The Tell-Tale Heart’ and delved heavily into opera and ballet. Growing up in the Middle East, perhaps, gave Copeland an edge. By the time he entered puberty, he had developed an encyclopaedic grasp of scales, modes and complex rhythms. But he is also considered one of America’s most revered, versatile interpreters of pop, rock/new wave and, gasp, jazz! In interview with Pennyblackmusic, Stewart Copeland elaborated on his current, creative projects and his warped-speed future . PB: You have hinted that you’re not crazy about jazz, but some of your earlier film scores bring to mind the genre. SC: I was raised to be a jazz musician, and then I made the discovery that you sure can enliven a dinner party with a comment such as, “the problem with jazz musicians is that they all suck.” Boy, does that turn a boring dinner party into an exciting one. It doesn’t have to be true, but it does get tongues wagging. Some of my best friends are jazz musicians. In fact, I qualify, I, myself, am a jazz musician. Ronnie Scott and Stanley Clarke equals “I’m a jazz musician.” I can say what I want. PB: What are some of your favourite songs that you have performed with Sting? SC: ‘Message in a Bottle’, ‘Bring on the Night’, ‘Can’t Stand Losing You,’ King of Pain’ – I’m not that wild about ‘Wrapped Around Your Finger’ but I enjoy playing it because I use a percussion rig, which is fun. There are so many songs that I really like—‘If I Ever Lose My Faith in You’, ‘Fields of Gold’. I’m a sucker for his music; not him so much. PB: Do you see yourself doing more songwriting in the future? SC: Only if necessary. I guess, writing opera could be called songwriting. But as far as a three-minute pop song, there are youngsters that need to be doing that. PB: Regarding ‘Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ’, did you conceptualise the score by creating character themes or by focusing on universal emotions? SC: Mostly with regards to the film, I’d already written the music for an arena production, and I was commissioned by a mad German impresario who had staged ‘Ben Hur: A Tale of the Christ’ in arenas, the whole story with the chariot race, the pirate battle, the whole schmear and he commissioned me to write the music for this live production. It opened in the 2002 arena, played across Europe and did its thing. When it finished its run, I still owned the music, and I was very fond of it and decided I wanted to do concerts with it. My manager, Derek Power, and I were talking about doing it, perhaps, with some kind of visual images of chariots or something, but then he had this idea of setting the music to the 1925 film and as soon as I took one look at the movie I started drinking the Kool-Aid. I realised that I have the Messala theme, I have the Jesus theme, I have the jealousy, the race, the battle and the themes, not so much for the different characters, but for the dramatic motifs: jealousy, revenge and redemption and I have those theme. So, I took the music I had for the arena production and scored the movie using those themes. PB: You painstakingly cleaned and restored the original film. Would you undergo this process again for the right film? SC: Well, it was a long time, yes, but it was deeply engrossing and I enjoyed every minute of it. PB: So, you would go through this process again if the right film came along. SC: I think so. PB: You’ve talked about pacing in rock music. How does this apply to orchestral music? SC: The modern composer coming out of Julliard is in competition with Stravinsky and Mozart. I’m not. I just want to burn down the building, and I’m pretty sure that it’s possible with sixty or ninety guys to rock the joint. The music is not rock music by any means — it’s not that simplistic, but I have brought with me the values of interaction with the audience. I want to wake people up. If I’m watching Brahms, I want to close my eyes and tell the audience around me to shut up so I can get my Brahms, but that’s not what I’m here for. I am more about excitement and celebration. That’s what my music is about, and so I’m using those sixty guys for my purpose which is to light the place up. PB: You’ve composed using the influences of Africa, Indonesia and Italy. Are there any other types of world music you would still like to explore? SC: Yes and no. Well, I guess the most obvious answer is the culture of orchestral music, just those textures. I love ethnicity. I love those shades of the beats and the atmosphere. I have derived great creative sustenance from world music but that’s not my mission. Right now I’m beguiled by the rich textures that are available with an orchestra, and that’s sort of where I’m at in my life—how to take those textures and that power and do something cool with it. PB: You are onstage playing percussion for the entire performance. But being the composer, do you ever want to observe, stand back,take it all in? SC: Well, I can. Unfortunately in classical music with the unions you can’t, as you do with a rock concert, record every show, but I don’t have to play every show. The Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra commissioned a concerto for percussion and orchestra, and I got to sit in the back of the hall while the percussion section does it all. The Dallas Symphony commissioned a piece for gamelan and orchestra, so there are pieces out there that I just get to watch. I do enjoy playing and I am working on another concerto for drums and orchestra, which is actually an expansion of the piece I did for Liverpool. I did one sixteen-minute movement for them. I have two more to write and I’ll be playing that. I enjoy playing with a big orchestra, but I also enjoy going to the show and not having to play. PB: You once said, “Playing someone else’s kit isn’t like driving someone else’s car; it’s more like wearing someone else’s clothes.” Are you generally able to have your equipment transported and set up exactly the way you want it? SC: I have a drum tech that’s been with me for thirty years, Jeff Seitz, which means that whatever suit of clothes it is, by the time he tailors it, that fits perfectly. PB: Growing up in Lebanon, you were exposed to non-Western modalities, so when you came back to America did you find rock boring? SC: Not at all. It was like coming home. To me, it was new and exciting and the modalities that I grew up with were pretty well same old same old because they were ubiquitous. And now as an adult, I realise how exotic they were. I moved back to them. With ‘Ben-Hur’, there was a lot of Middle Eastern flavour in there. PB: What instruments contributed the most to creating that sound? SC: At different spots there were different instruments. There was one spot where we’re in the spot with Ilderim, and he’s basically conspiring, and when I was recording the music to the arena show I went to Istanbul and recorded a lot of local flavour. And one of the lines that the trombones came up with—Drrrahdadumdadada—was very ethnic on trombones and so I put that in the score, and to see the guy in the Chicago Symphony hitting that was kind of cool. For some of it, I actually kept the recordings and ran those as an element with the orchestra. PB: Were you reading the score throughout or improvising in part? SC: No. As far as the score goes, I memorised it, but I haven’t memorised what I’m doing, I memorised what the orchestra is doing, and so what I’m doing with the music that I’ve memorised is organised. I know where the hits are and I pretty much know what I’m going to do, and on the fortalice, the tuned percussion, the mallet instruments, I pretty much have to hit the right notes and so over on the secondary percussion unit I do have a score, which I’m following just to remind me because those fortalice are very unforgiving if you hit the wrong notes. For the drums, I do it all from memory or make it up as I go along. I’m the world’s worst session musician because I don’t take directions and I don’t bother to remember anything. I know what I know and I make it up as I go along. It’s different every night. PB: Did you and conductor Richard Kaufman work independently during rehearsals for ‘Ben-Hur’ or did you conceptualise together?] SC: Richard was very hands-on. We had a lot of meetings and he goes the extra nine yards. He really does care about the music. Other conductors that I work with sometimes you meet them on the podium. Then you say goodbye after the show, and that’s it. With Richard, he came over to my house; he worked on lots of different aspects of the score. Mostly what we worked on is how to cue it, how to navigate through it. He doesn’t argue with me about what music is, just now to navigate it and we have streamers and different ways of knowing where we are in the score, particularly since he doesn’t know what I’m going to come up with at any given performance. PB: You’ve written works based on the writings of Edgar Allan Poe and classical works like ‘King Lear’. Is there a pattern or theme that you generally try to follow? SC: I should probably try to look for such a theme but I don’t know that there is. I was working on an operatic version of ‘Finnegan’s Wake’, but, unfortunately, it’s not public domain yet. That has historical characters, but there isn’t one guy. PB: What qualities do you look for when you jam or collaborate with other musicians? SC: Listening. So many musicians learn their parts and play them. What I need is someone who is listening. They can be staring off into space as long as their ears are listening, and as soon as I sense that they’re not listening they’re going to get a drumstick in back of their head. PB: Your Sacred Grove studio is a treasure trove for historic instruments. You have something unique related to Booker T. Jones, for example. SC: It’s a Model M 1948 Hammond organ. It’s the one that Booker T. used for ‘Green Onions’. I’m a denizen of EBay and that organ I got for fifty bucks. The Leslie cabinets - I had to modify for the organ because Leslie and Hammond were enemies and it wasn’t until decades later of this co-dependence that they finally had a paix monde. 1948 was before the invention of the Leslie, so to make my Hammond drive the Leslie, there’s a mosh that you have to do, so I have trombones, celli, string instruments of every kind: tubas, trumpets the woodwinds, as well. PB: What have been the best memories of your rock/punk career? SC: Shea Stadium was pretty cheerful. Touring with Oysterhead was extremely cheerful. PB: You don’t like drum solos. SC: I just don’t get around to it. My instrument is an accompanying instrument and that’s what I like to do best. I played two drum solos in my life. One was on ‘Letterman’ on his drum solo week, and the other was in Africa when I was in a chicken wire cage surrounded by lions - they were trying to get into the cage, and I’m there on my drums, and I had to be real quiet because the drums were so loud for their ears that it would drive them away. So, I’m kind of air drumming on this drum set. Now the lions are building up in confidence and we have their cage filled with meat to help make them more aggressive, and suddenly I hear this thump right behind me, and there’s a big one right there. In front, one of them has reached its claw under my bass drum, and its claw is pulling on one of the lugs on my bass drum, and I’m thinking, “Okay, drum solo.” PB: Are there any musicians that you would still like to invite to your studio? SC: There are a couple that owe me actually because I occasionally get calls from people who ask me to play on their record. My deal is, you can’t afford me, but actually I’m real cheap. I’ll give you a day in return for a day. I won’t mention any names, but there are a few guys out there that still owe me and I’ll get them over to the Sacred Grove. PB: For a day of recording or a jam session? SC: I won’t take the whole day. They’ll come over for a party and we’ll jam. I’m not trying to make a record or anything like that and it makes it sound like a contract. It’s not like that at all. Come over to Sacred Grove. Just come over and hang. PB: Where are all the women drummers? SC: Karen Carpenter, Gina Schock (The Go-Go’s - LT), Sheila E. (Prince, Ringo Starr -LT). They’re all excellent. It may be that drums aren’t as lady like as being secretary of state and it’s the same with bass. With bass, there is a physical issue, which is that those big, fast strings are best played with big, fat fingers and that’s just a size thing, although Carol Kaye, a middle-aged white lady, was one of the funkiest bass players who played on a lot of our favourite Motown records. But there are good women drummers and it doesn’t take big hands or masculinity in any way. There’s no reason why women can’t play drums just as well as men. Sheila E. shows that that’s the case. PB: Speaking of hands, you have to guard yours. What’s your secret? SC: I don’t shake hands. When I see buddies coming at me with that big, raised hand to do a high-five, I present knuckle bump. My daughters’ boyfriends come over and want to do the firm handshake. They get a knuckle bump. They’re not going to prove their masculinity for their father-in-law by breaking my thumb. PB: You are constantly involved with creative projects. What do you see happening over the next few years? SC: I wish I could drop names. I had a breakfast meeting ,and I just finished a lunch meeting with two, big ass orchestras who want to do some extremely cool stuff and this afternoon, I can drop this name, I’m meeting with the Chicago Opera Theater about a piece that I’m going to be doing for them. Writing opera is the most fun of all. PB: And you don’t get intimidated by tackling such large-scale projects? SC: I’m not quite sure why I would be. I guess it may be daunting for artists, who are used to writing three-minute songs to write a ninety-minute song, but I’m now working on my fifth opera and I sort of specialise in large-scale endeavours. I know and have confidence in my own stamina and, when I start in on an idea, I know I’m going to finish it. I guess that’s what it takes; just the knowledge to know that you can do it and other musicians might look at a huge mission and say, “I don’t know where to start,” but I’ve been around long enough and I’ve done enough of these to know that, well, there is a there there and finishing such a gigantic work is possible and dang rewarding. PB: The contemporary audience is accustomed to multi-tasking, so looking at the big screen and listening to you and the CSO works at this point in time. Do you think this kind of 3D performance would have worked with earlier audiences? SC: I often wonder and I am sort of confident that Fred Niblo, who directed ‘Ben-Hur’, would have been happy with the results. He would have thought that I, as editor, was short changing the audience by giving them less than two hours and forty minutes. He might have looked askance at the ninety-minute version, but by all accounts the story is completely intact. Many people who have seen the show have said, “What on earth was the other hour?” PB: I doubt we would have suspected it was an edited version if we hadn’t been told. SC; There are a couple of major plot points that I ducked. How does Esther, the love interest, know that the mother and sister are in the leper colony? How does she know that to go and save them? And the reason is that there is a forty-minute scene where they arrive and are released at the old Pera Palace. Esther is there and they make her promise not to tell Ben-Hur because he’ll try to find them and become infected. That’s how she knows, and I cut that very long scene. And the other very long scene is where he’s in the galley and the Roman general gets talking to him and realises that he’s a man of quality and has been unjustly imprisoned, and at that moment the pirates attack and he says, “Well, cut that guy loose.” That’s why he doesn’t drown with all of the other slaves and that’s why he saves the general’s wife. And in my version we kind of glide right over that and he saves the general’s wife - because it’s a movie. PB: So, pretend you’re a super hero, Stewart. What’s your power? SC: Time-travel. PB: You seem like you would be pretty good at that. SC: Well, I’m crap at it, actually. I haven’t managed to go backward or forward in time even for a minute, but that’s what I would like to be able to do. PB: Thank you. Photographs by Philamonjaro http://www.philamonjaro.com

Article Links:-

http://www.philamonjaro.comhttp://www.stewartcopeland.net/news/news.html

Band Links:-

http://www.stewartcopeland.net/https://www.facebook.com/StewartCopeland/

https://twitter.com/copelandmusic

Picture Gallery:-

live reviews |

|

Police Deranged For Orchestra - Blossom Music Center, Cuyahoga Falls, Ohio, 11/9/2021 |

|

| Philamonjaro watches and photographs Stewart Copeland rearrange The Police catalogue with the Cleveland Orchestra at the Blossom Center in Ohio. |

| The Invention of Morel, Chicago, Illinois, 24/2/2017 |

most viewed articles

current edition

Carl Ewens - David Bowie 1964 to 1982 On Track: Every Album, Every SongArmory Show - Interview with Richard Jobson

John McKay - Interview

Colin Blunstone - Thalia Hall, Chicago, 16/7/2025

Billie Eilish - O2 Arena, London, 10/7/2025

Bathers - Photoscapes 1

Visor Fest - Valencia, Spain, 26/9/2025...27/9/2025

Loft - Interview

Sir Tim Rice - Interview

Robert Forster - Interview

previous editions

Manic Street Preachers - (Gig of a Lifetime) Millennium Stadium, Cardiff, December 1999Heavenly - P.U.N.K. Girl EP

Beautiful South - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

Oasis - Oasis, Earl's Court, London, 1995

Peter Perrett - In Dreams Begin Responsibilities Interview Part One

Boomtown Rats - Ten Songs That Made Me Love....

Coldplay - Wembley Arena. London, 16/8/2022

Prolapse - Interview

Pixies - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

Trudie Myerscough-Harris - Interview

most viewed reviews

current edition

Davey Woodward - Mumbo in the JumboSick Man of Europe - The Sick Man of Europe

Lucy Spraggan - Other Sides of the Moon

Amy Macdonald - Is This What You've Been Waiting For?

Phew, Erika Kobayashi,, Dieter Moebius - Radium Girls

Bush - I Beat Loneliness

Suzanne Vega - Flying With Angels

Alice Cooper - The Revenge of Alice Cooper

Blueboy - 2

Cynthia Erivo - I Forgive You

related articles |

|

Stewart Copeland: Interview (2014 |

|

| Lisa Torem chats to former Police drummer Stewart Copeland about his solo career and composing for film and television |

Pennyblackmusic Regular Contributors

Adrian Janes

Amanda J. Window

Andrew Twambley

Anthony Dhanendran

Benjamin Howarth

Cila Warncke

Daniel Cressey

Darren Aston

Dastardly

Dave Goodwin

Denzil Watson

Dominic B. Simpson

Eoghan Lyng

Fiona Hutchings

Harry Sherriff

Helen Tipping

Jamie Rowland

John Clarkson

Julie Cruickshank

Kimberly Bright

Lisa Torem

Maarten Schiethart