In Dreams Begin Responsibilities - #3

by Steve Miles

published: 7 / 4 / 2021

intro

In his column ‘In Dreams Begin Responsibilities’ European Sun and The Short Stories’ Steve Miles reflects on the role of silence in music.

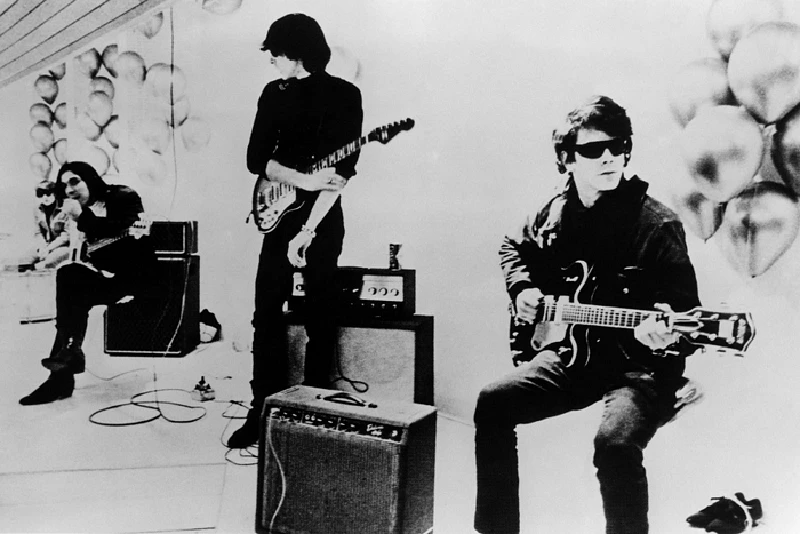

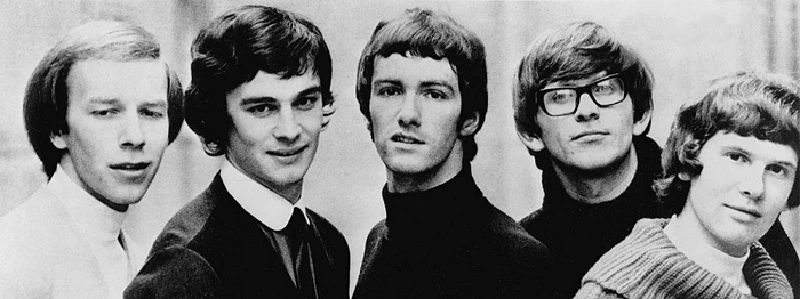

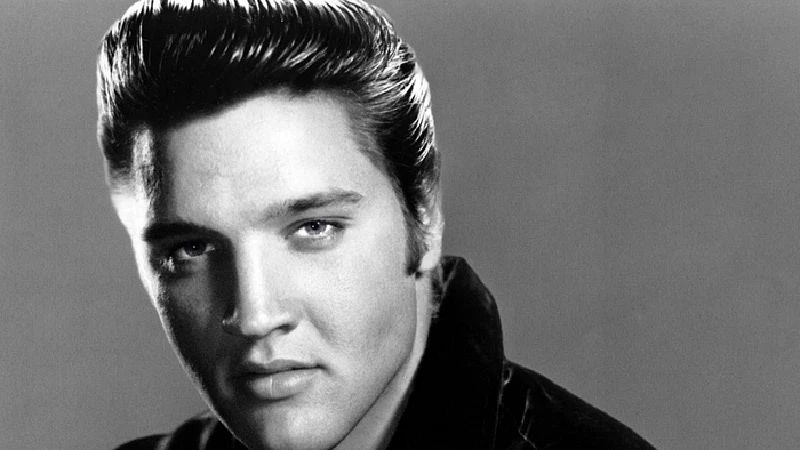

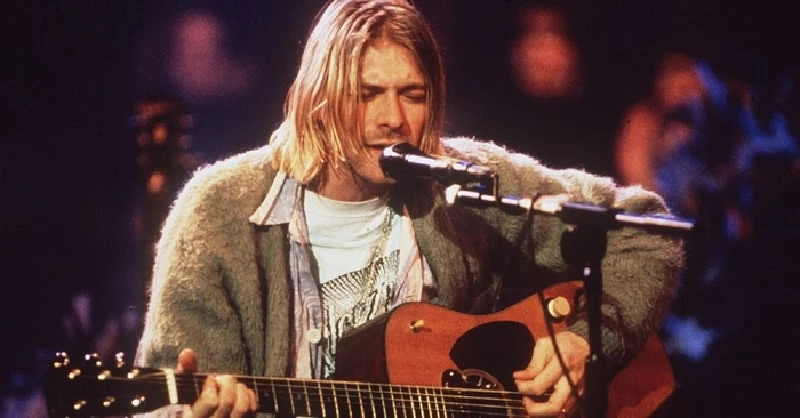

“Pretty girls, pretty boys: have you ever heard your mummy say, ‘Noise Annoys’?” My first two columns were about what punk meant to me. I had intended to write about Doug Yule in this one, but am leaving that now for another day. The editor of this magazine said I could write about anything as long as it was vaguely about music – so I decided this time to write about silence. My first partner was genuinely traumatised by other people’s sounds – neighbours, in particular, but also people talking on trains and buses, cars going by; it got under her skin to a degree that was very troubling to her. Whether I caught that from her, I’m not sure, as I don’t remember being distressed by those things as a teenager, but I do now find other people’s life noises disturbing. Power tools in nearby gardens and people who take calls in the quiet compartment on trains get under my skin more than they should. And as for the ‘music’ you are forced to hear while waiting to speak to a human to talk to about your insurance, well… That said, I most definitely prefer music to noise, and, for that reason, have always been a big fan of headphones. Headphones block out noise but replace it with something better. I wear them a lot, both inside and outside, because I live right next to a road. I’ve tried audio books but loud lorries drown out whole sentences and as for the roaring motorbikes that think it’s a racetrack – well, they made our children cry when they were toddlers and often still make them jump now. Only music really works to make those bits of noise pollution go away. Music also drowns out the uproar in my own head. With audio books I often find I’ve trailed off into my own worries and forgotten to listen to the story; with music the two can co-exist but in a way that regulates my inner demons much more effectively. When I first got a pair of headphones, it was a revelation. I heard much more in songs than I’d heard before, and with that I learned to understand more how songs were put together, and how each part contributed to the whole. In turn, listening to music became more rewarding and more fun. Over time I began to realise how important the structure of a song was. The stop-start arrangement of Buzzcocks’ B-side ‘Noise Annoys’ (1978), for example- the song quoted at the beginning of the article - is both unsettling and exhilarating, and the spaces created by the intermittent gaps in the rhythm make the song’s concept, and the repetitive lead guitar parts all the more effective. It’s not my favourite Buzzcocks song by any means, and they explored structure much better in a number of key early songs on the first three albums (before completely losing that experimental edge after they reformed) but I mention it here because the lyrics, of course, fit my theme so well. Its A-Side, ‘Love You More’, thrills not only by coming to a polished bang about half way through the expected length of a single in 1978 (it’s 01:45) but also by being the spiky aural opposition to the prevailing times’ favoured fade-out. Oh, Lord, how I hated DJs talking over records as they came to an end in those days! I even got into an argument about it the one time I visited a local radio station with my friends. We took along ‘The Missionary’ (Josef K, 1982) for him to play and my bolshie insistence, with typical teenage self-righteousness and lack of tact, that he wasn’t to speak until the last notes had died, made an embittered enemy of him at once. (It does have, to be fair, one of the purest dying chords you will hear on record, if you listen carefully.) How great it was when the DJs instead got caught unawares by the unanticipated end of ‘Love You More’! But I digress. Of course, if you love vinyl, there’s never silence, but instead the familiar quiet crackle of the stylus in the bits between the music - but some people love that the most, so it counts the same. For another great example of the power of a brief silence, have a listen to the opening of the original version of ‘I Love You’ by The Zombies (1965 B-side). The song begins, effectively, with a stop. After just ten seconds there is a startling halt and restart which contrasts comically with the ensuing lyrical repetition of the title phrase, ‘I Love You’, an incredible thirty-three times in just under three and half minutes. But it makes perfect sense because the whole song is about someone not knowing how to speak to his loved one: “I should tell you just how I feel and I keep trying/But something holds me back when I try to tell you.” Therefore the fabulous fractured intro is the equivalent of someone opening their mouth to speak and no words coming out. The little thrill of that unexpected hiatus gets me every time. Written by their bassist, Chris White, the song’s unusual structure – the chorus comes before the verse – also gives it enduring appeal, along with the trademark sad choirboy vocals of Colin Blunden and the virtuoso jazz pop organ of Rod Argent, although it goes downhill after those first ten startling seconds. (Be warned, it was either re-recorded or subsequently released in an edited version s and the version without the all-important ‘false start’ is pretty prevalent.) Elvis Presley's first RCA release and his first million-selling single was, of course, ‘Heartbreak Hotel’. A basic blues song, it stands out in musical history because of Presley’s passionate, uniquely charismatic vocals, and the dramatically echoey production, but also, crucially, because of its arrangement. Think of it, and you think of the high energy of early rock’n’roll. Hear it, and you hear high energy rock’n’roll. But listen to it and it’s barely there; it limps along with the same wounded self-pity that drips from Presley’s mournful voice (John Lennon called it “hillbilly hiccupping”) coming alive only in the solo when the raindrop-piano and Scotty Moore’s reverb-drenched solo merge. It’s corny but it works – the music creates a lonely street for the heartbroken singer to walk down. Despite the remarkably sparse and quiet overall feel of the song, it’s only when you listen super-carefully that you hear the rhythm acoustic guitar of Chet Atkins in the background. It’s a song whose space and silence make it the classic it is, a song that makes ‘”room/For broken-hearted lovers/To cry there in the gloom.” One of the most humiliating episodes of my life - if something which no-one else but yourself has ever known (until now) can be humiliating - occurred when I went in search of ‘nature’s peace’ in my early twenties. Somehow, though I was on the dole, I had acquired the loan of an old moped and a second-hand sleeping bag that was supposed to function instead of a tent and keep you warm and dry by itself. I duly rode out to Dartmoor, found a wild spot, and hunkered down for the night. The sleeping bag did up right over your head, like a little cocoon. I think it did work for keeping me quite warm, but, of course, with no tent, it certainly left me unprotected against anything solid. I don’t think I had a torch or food or anything with me other than this quilted covering and my bucolic dreams of being close to nature. I don’t quite know what I expected and I don’t remember how long I lasted but it wasn’t even half the night. That silent, desolate, remote spot, once it got dark, became a blitzkrieg of noise and movement. It was a blustery night and the wind alone made a barrage of noises that I could hear far, far more loudly in the dark, once my ears had adjusted to the levels, than in the evening light. Time and again I zipped down the top of the sleeping bag and looked about frantically for the fox, badger, sheep or bear that I was sure was scuffling about my head, about to bite my leg off or trample me into the moor. The bushes cried like wailing souls and the trees hissed warnings. Even the grass seemed to boo and hum. I learned a lesson that night about why humans built houses and formed villages and cities. I also learnt that silence doesn’t really exist, and as I tootled back in the middle of the night with my tail between my legs, humbled by an acute a sense of failure, listening only to the sound of the moped’s pottering engine and wind around my ears, I would have given anything for a good pair of headphones to take the sting of disillusionment away. In my view, there’s not enough use made of silence in modern music. I don’t have the expertise to prove this by studious examples, but it feels to me as if old blues, reggae, and jazz have more variety, more stop and start, more light and shade than most modern chart and club music. I loathe almost all music that starts with a beat that you know will underpin the whole song relentlessly and unchangingly. Especially when someone drives past my house with their sound system so loud that I have to endure it as they go by! And as you will know if ever that’s happened to you, from that blessed first second when the car has driven out of hearing range, sometimes the merest snip of silence can evoke the strongest emotions. As with life, so with music, and of course, the gospel text is always The Velvet Underground. In this case, it comes at the start of side two of ‘White Light/White Heat’ (1968), in a seminal moment I am by no means the first to point out. ‘I Heard Her Call My Name’ consists in essence of a common and straightforward enough rock chord sequence, played at a moderately upbeat but by no means particularly intense tempo on rhythm guitar. The words, which I don’t fully understand but which suggest insanity, paranoia or grief. are sung with an exuberance that borders on, but doesn’t quite stray into, abandon. So far, so normal. But it doesn’t sound normal. First, because it starts abruptly with an electric-shock squeal, for all the world as if the song was already playing before ‘record’ was pressed. Second, because the bass and drums pound incongruously fast compared to the rhythm guitar, not just manically but also thuggishly, almost as if imported from another song, or as if someone was being badly beaten up in the room next to the recording studio. And thirdly, because the lead guitar comes from your nightmares. From the first second, Lou Reed causes as much dissonant mayhem as he can in an ear-splitting lead that seems designed to cause mischief. In short, it’s a very noisy record. And whereas most songs that sound ‘loud’ or ‘messy’ at first become familiar and even comfortable with time, this song doesn’t. It always disturbs. It always makes you wince just a little. After a verse and a chorus, with carefully harmonising backing vocals worthy of a doo wop band, Lou Reed famously says, “Then I felt my mind split open” and the song suddenly makes sense. This is the sound of a breakdown: he scrapes and batters his fretboard and tortures his amp to get the most unsettling and unpleasant noises he can, evoking through sound the hysteria he spoke of. The anguished ‘solo’ ends and the pattern repeats for the second part of the song. At the repeat of the guitar break Reed yells, “And then my mind split open” with even more gusto, before returning to imitate the noise of mental collapse with even greater intent. This lead break continues to the end of the song, screaming through not one but two bizarre segments of about ten seconds where the bass inexplicably vanishes, like a headache receding momentarily, emphasizing further the chaos that is the song. “Hey, Steve”, I hear you thinking: ‘You have been talking about silence and yet so far all you’ve discussed is noise? What gives?’ I’m glad you asked. Because in all that cacophonous din, the most powerful part of the whole song is silence: a micro-second between the second ‘split open’ and the ensuing ‘solo’. That silence stands out. Not if you’re not listening carefully. But once heard, it’s never forgotten. It defines what comes after. It’s incredibly brief, and almost certainly not even intentional, but without it, the song for me would only be half of what it is. That’s the power of silence. Lou Reed, for all his strengths, was only ever as good as his collaborators. And thus it was that he resurfaced from some very inconsistent recordings in the seventies with the first four piece band he’d had since The Velvets - and the first time he’d had musicians who would push him - in 1981 with ‘The Blue Mask’. On this record, Reed wrote about personal topics, from the heart, not hiding behind characters or voices that weren’t his own, as he did so often in his career. On his previous album, ‘Growing Up In Public’ (released April 1980, but very much of the end of the Seventies in spirit) he had already begun to drop the ‘Lou Reed’ persona that he had cultivated in the past six years to both pander to and protect himself from the media (“I do Lou Reed better than anybody’” he snarled on the live ‘Take No Prisoners’ album in 1978) reflecting on that process in the title track. But that album was still heavily defensive emotionally and intellectually. With ‘The Blue Mask’ the lyrics came without pretension and the music without insincerity or stale tropes. The reinvention of a ‘true’ Lou Reed was masterfully captured in his new wife Sylvia’s cover design, which posited the ‘mask’ of Lou Reed as the famous cover image from ‘Transformer’ (1972). You can hear the honesty on the record in his voice, which on the whole lacks the mannerisms he had toyed with through his solo recordings to that point. The album has a host of highlights, and I could write about it at great length, but one that stands out is the fervid and unforgettable ‘Waves of Fear’ in which he recounts what I suspect to be the sufferings of addiction: “I curse at my tremors, I jump at my own step/I cringe at my terror, I hate my own smell/I know where I must be, I must be in hell” The songs starts with heavy portentous bass drags by Fernando Saunders, who went on to become Reed’s longest collaborator, over which the drums pound to herald in the two guitars, Reed’s rhythm and Robert Quine’s downtuned lead. The lyrics are relentlessly bleak and the musicians go all out to capture it. Saunders’ bass motif is simple enough but it echoes the night terrors that are being described to perfection, and he switches to melodic higher notes under the solo as a perfect counterpoint to what that evokes. Doane Perry’s drums crash and pound like an over-rapid, thumping heartbeat, and Quine’s lead cowers, screeches and squeals throughout. It doesn’t always work when musicians to try to capture the exact feel of lyrics in sound (though the best songs usually match the moods of the words and the music) but in this case the band nails the horrors depicted impeccably. After the verse partly quoted above, Reed repeats the words, ‘Waves of Fear’ four times, before a short breather, and then the solo. Now, how on earth can you play a solo on a song like this? Quine knows. He replicates the words, and even the delirious tremors of the song’s story in sound. His fingers on the strings spit bile and cough up blood as his guitar trembles, sobs and whimpers to the end of the song. Like ‘I Heard Her Call My Name’, it’s not a song you can have in the background while you have your tea, or make love, or entertain friends. If you hear it, it’s moving; if you listen to it, it’s painful, and cathartic, all at once. Maybe I feel too much when I listen to songs or think too much about them? I do wonder. Do other people feel the same? Perhaps you think I’m a bit odd for hearing so much in a solo? But it is what it is. Anyway, it’s not the studio recording just described that is pertinent here, but the live performance released on ‘A Night with Lou Reed’ (1983). I’d never seen Lou live when I first saw this and I’d never seen Quine, and it was a significant moment for me. It had never occurred to me how someone actually played what I was hearing on that record, and when the band launched into ‘Waves of Fear’, Reed smiling incongruously warmly at Saunders as the nightmare kicks in, with the underrated Fred Maher on drums, I didn’t know what to expect. As the vocals end and it’s time for Quine, the camera gets closer to the accountant with shades who is playing the Stratocaster. Out comes a lead guitar which is very different from but equal to the studio version, and then just as he gets gnarly and Reed approaches him, Quine stops. Dead. Starts again. Stops. Dead. Climaxes. Like a heart stopping. Like a switch clicking on and off. What does it mean? Why does he do it? Who knows? But does it blow your socks off, yes it does. Watch it! It’s around 02:47 but makes no sense out of context so watch the whole thing, and preferably the whole gig, which builds it up nicely. My last two examples of the power of silence are also both performances rather than studio recordings and the images are inseparable from the sound in my feelings for them, so the YouTube links are below, as they are for all the songs discussed here. When my band The Short Stories starting playing as just acoustic guitar and bass, I found people listened much more closely to us than they ever had before, which was great, especially since my lyrics mean a lot to me. We got more attention by making less noise, which was a bit of a revelation. Sadly, we never recorded like that, though we have tried to capture some of that vibe on the ‘European Sun’ debut. And that was always the point of the long-time US series ‘MTV Unplugged’ – a quieter, more intimate communication with the musicians. Unfortunately, most of the bands on it were awful. But there was one notable exception. Recorded on November 18th 1993 in New York was an ‘Unplugged’ like no other. The band in this episode played six covers out of fourteen songs, scarcely any of their ‘greatest hits’ and closed with a song that few in the audience would have heard of at all, all while surrounded by lilies and candles. At the end of this show, looking delicately beautiful and sounding vulnerably defiant, wrapped in a baggy beige/grey cardigan and perched on an inexpensive office chair, Kurt Cobain turns to the microphone and says, “Fuck you all, this is the last song of the evening” (edited out from the original showing) before beginning his cover of old folk classic, ‘In The Pines’, fixed in the blues canon as ‘Where Did You Sleep Last Night’ by Leadbelly, to close the show. Cobain had history with the song, playing guitar on Mark Lanegan’s debut solo album’s recording of it in 1990. But neither that, nor the Nirvana home demo that his since been released on the ‘With The Lights Out’ boxset, nor any other bootleg live band recordings of this song that I’ve heard, show a fraction of the passion that is captured in the MTV performance, where every bit of Cobain’s existential anxiety, frustration, and melancholy is poured into a song that on the face of it, is an unlikely vehicle for his alienated outsider Grunge ethics. After two choruses and a brief interlude (prefaced by “shiver for me” by Cobain, in faithful deference to the Leadbelly recording) the band drop down to a quiet space, Cobain almost whispering the words. When the final verse begins, Cobain does with his voice what Nirvana were famous for with their arrangements – what ‘Smells Like Teen Spirit’ did so archetypally: he cuts from quiet to noise, stamping on the metaphorical fuzz pedal of his vocal chords. He shifts up an octave and switches from the relatively gentle growl of the previous part to a heartbreaking primal scream, controlled yet desperate. Undercut by Lori Goldston‘s cello coming back in, the emotional thrust is overwhelming, but there is still more to come. As the song comes to the climax with just the refrain “I will shiver the whole night through” to go, the band stops (untidily) at the elongated and throaty cry of agony which is “shiver”. Cobain, alone, squawks “the whole”’, his eyes still firmly shut, as they have been through the whole line. Then his eyes pop open, and he looks almost startled to find himself not alone, and he sighs, before every last bit of his energy goes into the haunting, “the whole night through”. The band plays the riff through again, and it ends. That sigh – not the brief pause that precedes it, or the primal pain of his vocals – is the moment that makes it, for me, one of the most essential and emotional performances in music. It’s just a short soft and possibly involuntary escape of breath, yet it’s Cobain’s finest moment. But it was before I was born, when television was still blurry and black and white in more ways than one, that my favourite expression of the power of silence in music can be found. This is cheating really because it’s a facial expression, but I don’t care because it’s so wonderful, it fits here and it’s the best example I know of film enhancing sound. Billie Holiday wrote and first recorded ‘Fine and Mellow’ in 1939, and documented it a number of times, but the most memorable take for me came in a TV special on December 8th 1957 for a programme called ‘The Sound of Jazz’ which is now, wonderfully, readily available on the internet. After half an hour of jazz greats it’s Billie’s turn to sing and her slot begins with a pre-recorded voice-over where she sounds terrible, but explains that, “There’s two kinds of blues: there’s happy blues and there’s sad blues… The blues is sort of a mixed-up thing; you just have to feel it.” As the track starts, Billie sits surrounded by her friends, singing to and with a quite extraordinary line-up of musicians who take the song into another world. She sings the first verse with effortless emotion, that croak of her later years’ voice just underscoring the melancholy. Ben Webster takes the first solo on tenor sax, and Lester Young follows. The lighting, the sympathetic look-and-response editing, and the intimate close-ups of the filming makes you breathe the music right into your lungs, feel the mood in your veins. The way they are all listening to each other stands out. It’s so special, so important. And you can see it means more to them than music to make the sounds they do. And that music means more to them than a job. The spaces in this performance are again, essential. Here it comes from so many superb musicians, each of whom respect each other, and listen to each other, working as one. The gaps inserted in the trombone solo that comes after the second verse, and the stop-starts of Coleman Hawkins’ sax solo after the third that is picked up and taken to the limit by Roy Eldridge’s trumpet straight after: all show to perfection the power of silence to cast light on sound, as does the impeccably judged syncopation as Billie returns for her final verses, the bass, drums and piano throughout casting highlights on the vocals and the soloing. But the moment of silence that I am highlighting here happens early in the song. It’s not really silence but it’s the look on Billie Holiday’s face as she hears her fellow musicians play. Alcoholic, addicted, unhealthy, oppressed best friends, Billie looks on lovingly as Lester Young plays his part and smiles the smile of someone who is so happy to hear the vibe she wants to evoke captured so perfectly. Just sixteen months later, aged 49, Young died from his alcoholism, and four months after that, aged only 44, Holiday followed him. As Lester plays, she nods appreciatively, earrings jangling, grateful and happy. And then the mood of the song itself comes back to the fore and with it the melancholy. So she briefly shakes her head – shakes her head at the sadness and the regret. It’s ‘good grief’ – she’s sad because she’s blue, but glad that her music captures it; joyful that her friends can encapsulate the feelings, downcast because they feel the unhappiness too. And that, of course, is what great music and great art does: allows us to see the emotions that others are feeling. I feel sad. I paint it blue. You see the blue. You see the sadness. But there’s a happiness that comes from that sharing, that connection, and that breach of loneliness that derives from communication. That is the power of music. The rest is silence.

Also In In Dreams Begins Responsibilities

In Dreams Begin Responsibilities (2024)

In Dreams Begin Responsibilities (2023)

In Dreams Begin Responsibilities (2023)

In Dreams Begin Responsibilities (2023)

Article Links:-

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h7gs7dMeI-chttps://www.youtube.com/watch?v=l1Fd3lzviI4

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e9BLw4W5KU8

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fEWkHAIQ3gs&ab_channel=TheVelvetUnderg

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hEM

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YKqxG09wlIA&ab_channel=StephanieCozy

Play in YouTube:-

Picture Gallery:-

most viewed articles

current edition

Carl Ewens - David Bowie 1964 to 1982 On Track: Every Album, Every SongArmory Show - Interview with Richard Jobson

Colin Blunstone - Thalia Hall, Chicago, 16/7/2025

Visor Fest - Valencia, Spain, 26/9/2025...27/9/2025

Bathers - Photoscapes 1

John McKay - Interview

Loft - Interview

Robert Forster - Interview

Billie Eilish - O2 Arena, London, 10/7/2025

Sir Tim Rice - Interview

previous editions

Heavenly - P.U.N.K. Girl EPManic Street Preachers - (Gig of a Lifetime) Millennium Stadium, Cardiff, December 1999

Beautiful South - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

Oasis - Oasis, Earl's Court, London, 1995

Pixies - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

Boomtown Rats - Ten Songs That Made Me Love....

Trudie Myerscough-Harris - Interview

Prolapse - Interview

Peter Perrett - In Dreams Begin Responsibilities Interview Part One

Simon Heavisides - Destiny Stopped Screaming: The Life and Times of Adrian Borland

most viewed reviews

current edition

Amy Macdonald - Is This What You've Been Waiting For?Sick Man of Europe - The Sick Man of Europe

Lucy Spraggan - Other Sides of the Moon

Phew, Erika Kobayashi,, Dieter Moebius - Radium Girls

Davey Woodward - Mumbo in the Jumbo

Alice Cooper - The Revenge of Alice Cooper

Bush - I Beat Loneliness

Suzanne Vega - Flying With Angels

Blueboy - 2

Cynthia Erivo - I Forgive You

Pennyblackmusic Regular Contributors

Adrian Janes

Amanda J. Window

Andrew Twambley

Anthony Dhanendran

Benjamin Howarth

Cila Warncke

Daniel Cressey

Darren Aston

Dastardly

Dave Goodwin

Denzil Watson

Dominic B. Simpson

Eoghan Lyng

Fiona Hutchings

Harry Sherriff

Helen Tipping

Jamie Rowland

John Clarkson

Julie Cruickshank

Kimberly Bright

Lisa Torem

Maarten Schiethart