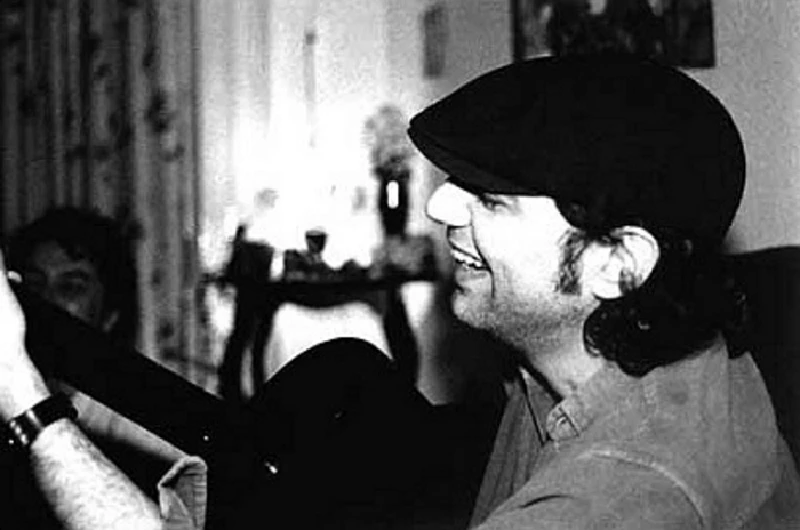

I met Sal Bernardi in 2013 after he had participated in a vibrant set with Rickie Lee Jones at Chicago’s Old Town School of Folk Music. His guitar and accordion playing gave the material an ethereal glow. The New Jersey-raised musician is so easy to talk with that a quick hello turned into a half-hour discussion about being an expatriate, missing one’s native tongue and the inspiration for a few of his original tunes, which had been sprinkled throughout the set. It was one of his most unforgettable songs, ‘Pretty Poison’ that piqued my interest in his compositional skills and talent for narratives. Sal lives in Paris and can often be seen wearing a distinctive chapeau and dark shades, which contributes to his overall mystique. It’s no wonder he served as inspiration for many of Rickie Lee’s free-flowing albums, and that he contributed epic melodies and beatnik type lyrics to some of her favourite songs. Devoting his life to music, Sal is a multi-instrumentalist and has performed with the Blue Nile, Elliot Murphy, Willy DeVille, Buzz Feiten and Niels Larsen, although the list goes on and on. In interview with Pennyblackmusic, he discussed his relationship with Rickie Lee Jones, other collaborations, solo projects and the precarious nature of life on the road. PB: You first met Rickie Lee Jones in 1975. What was going on in your lives at that time and what led you to continue your musical relationship throughout the years? SB: In the 1970s, I had gone out west to San Francisco, a lovely city to hang out in, but there wasn’t much of a music scene. I was told that L.A. was the place to go for music, so I went down there to check it out. I only spent a few months, but while I was there I’d picked up a little gig playing piano for a comedy duo. We played at a bar called The Come Back Inn. I met Ricky there. We started talking about music and, as it turned out, we had similar tastes. I played her some songs that I had written that she kind of liked. A few years later, we met in New York City. She had just finished her first record and was doing ‘Saturday Night Live’. As far as the continuing musical relationship is concerned, I’m not really sure. It is “just one of those things,” I guess. The fact that I work cheap may have something to do with it. PB: When you toured with Rickie Lee Jones in the fall of 2013, we chatted after the gig at Old Town School, Chicago. You said it was nice to hear so much English being spoken. It sounds like you had had a case of homesick blues, perhaps related to living through another Thanksgiving in Paris. You’re from New Jersey, where the culture is a far cry from what we’d expect in Paris. What made you decide to move to Paris, how long have you been there and what’s it been like? SB: I came to Paris in the late 1980s for what was intended to be a short visit. Time began to fly and one thing led to another and voila! I’m still there. The part of New Jersey that I’m from is just outside of New York City. There are the obvious cultural differences, but there are some similarities between New York City and Paris. Some people say that Paris is like a pretty New York. I like it there but the language barrier cam get quite stifling. I’m always having to edit speech to be understood. One could lose one’s natural jazz by doing too much of that. PB: On that tour, you accompanied Jones alongside a cellist, Ed Willett. It seems that Rickie Lee often creates songs that are rubato in nature; songs that invite unexpected tempos or, perhaps, demand a degree of improvisation. Is that true? And, if so, what is the best way to approach these arrangements? SB: There was some rehearsing before the gig, but ultimately she will go to wherever she is going to go and the band will try to follow. It’s sort of like flying without a net, at times. PB: Rickie Lee’s impressions of you showed up in much of her music: “a weasel in a white boys cool”, for example. She has said that your lyrical gifts greatly influenced the album ‘Pirates’: “sad-eyed Sinatra” being just one of those references. Like a novelist, do you take quick mental notes of people that you come across? SB: There is a lot of fiction in “weasel.” A friend listened to it and said, “The lyrics don’t really seem to apply to you, but she’s copped your groove.” I don’t take mental notes, but I might absorb atmosphere of an environment as I perceive it and then reflect it in the music. When I was young and impressionable, I would travel around a lot. I spent a lot of time in Quebec City. I was playing in some little bars up there and had just started to hone my writing skills. Quebec City, an old French town in Canada, seemed kind of exotic to me, at the time - something to do with the 17th century architecture and the mid-20th century French girls. Some of that scenery began reflecting in the music that I began to write. ‘Theme for the Pope’ would be a good example of that. Also, the “sad-eyed Sinatra” line was taken from a song that I wrote that took place in the Quebec City dreamscape. Generally melodic ideas come quite easily. Lyrics are somewhat of a chore. A few years ago, a choir in Australia made a video, singing ‘Theme for the Pope’ on a bridge in Melbourne. It was posted on YouTube. It’s kind of interesting to see a little guitar plucking day dreams from back in the 1970s show up so many years later in the form of a choir. The post has since been taken down because of some copyright issues. PB: You collaborated with Rickie Lee on ‘Traces of the Western Slopes’ (1982, ‘Pirates’), ‘Flying Cowboys’ (1990, ‘Flying Cowboys’) and ‘Tigers’ and ‘Beat Angels’ (1993, ‘Traffic from Paradise’). When you performed your own originals, like ‘Pretty Poison’ live, the audience really took note of the irony. These songs have gone on to have lives on their own. Did these songs come to you easily or did they happen in stages? SB: ‘Western Slopes’ was a song that I began and Rickie finished. I came up with the chords and a vocal melody to the first verse. That bit came quickly. Then she wrote lyrics and added a chorus and some tripped out middle bits. If my memory serves me correctly, I think it took a while to complete. On that track I played harmonica parts through a harmonist effects pedal. We sort of tried to emulate a horn arrangement. When the album was released, a critic wrote a piece praising the atmospheric horn section. Lesson to be learned -if you try to sound like a horn section, a listener might actually think that it is a horn section, and your harmonica credit goes unnoticed. ‘Flying Cowboys’ started with some chords on keyboard. I began playing a guitar riff over it and lyrics were later added. I’m self-taught and approach instruments with a “fingers fall where they may and hope for the best” kind of attitude. In this case, the guitar riff served as sort of a droning thread through the song. The chord shapes were kind of unorthodox. On tours that I didn’t participate in, they were unable to do the song because the guitar players couldn’t figure out how to play the riffs, not because it was so difficult, but because the chordal fingering was so incorrect that any self-respecting studied guitarist wouldn’t think of playing from that angle. Sometimes a lack of lessons might bring something fresh into the mix. ‘Tigers’ was from another song that I had hanging around. It was kind of melodic, but didn’t really have interesting lyrics. At some point Rickie gave it some lyrics and we recorded it. To answer the question, I guess these songs were written in stages. PB: These songs have gone on to have lives of their own. Did these songs come to you at once or, like the others, were they written in stages? SB: ‘Beat Angels’ and ‘Pretty Poison’ weren’t collaborations with Rickie. They were some songs that I had that Rickie covered. Both those songs also came in stages. PB: At the end of the 1990s, you recorded with the late Willy DeVille in Memphis. The album, 2001’s ‘Horse of a Different Color’ garnered rave reviews. You co-wrote ‘Gypsy Deck of Hearts’, ‘One Love in One Lifetime’ and ‘Lay Me Down Easy’ with Willy, and the songs, whilst all heart tuggers, ranged in style. Can you elaborate on how you and Willy worked together and what those songs mean to you now? SB: Willy heard some demos that I had recorded, and invited me down to New Orleans to help write songs for his upcoming album. It was sort of an assignment. I didn’t know him personally, but I was familiar with some of his recordings. It was kind of interesting to roll into town, meet somebody, sit down with two guitars and start pulling songs out of nowhere, under the gun style. I was there for about a week. We wrote four songs. One of them didn’t make it on to the album because it had a Latin feel. The album was recorded in Memphis and they couldn’t find a Latin percussionist. When we were writing a song called ‘Lay Me Down Easy’, Willy took the hotel Bible out of the drawer and borrowed a few lyrics for the bridge. I said, “Isn’t that plagiarism, if not sacrilegious?” He said, “No, we’re just spreading the word.” I hope that God and Gideon are okay with that. He had a soulful voice. Sometimes he would come up with a lyric that I wasn’t too crazy about, but when he would sing it then it was just fine. It’s a good sounding album. The Muscle Shoals rhythm section played on the tracks. It has that real, greasy, southern feel to it. PB: When you spent time in Quebec, Canada, you wrote some songs in French and some in English. Do you think in both languages when you write? Do you feel that some ideas can get lost in translation? SB: I never wrote lyrics in French, but a few different people wrote French lyrics for a melody that I wrote ‘Theme for the Pope’ - a strange travel for that melody. Initially, a friend in Quebec wrote some lyrics and called it ‘Danse la Reve des Cleo’. Several years later, there was a film called ‘The Pope of Greenwich Village’. I think the film people were seeking soundtrack music. Rickie and I had reworked the song a bit and made a demo without lyrics. It wasn’t used in the film, but Rickie released it on ‘The Magazine’, calling it by the working title for the film “Theme for the Pope”. For the European release of the album, a writer here in Paris wrote French lyrics and titled it ‘Marrant de Duece’, I think. A few years ago a choir in Australia wrote some lyrics in French, calling it ‘L’amour’ or something. It’s kind of funny how a simple little melody could cause so much confusion. PB: One of your previous bands, Boneyard, consisted of you and Joe Vernazza, Dave Barry and Walter Pickwood. Your arrangement ‘Got to Believe It’ has one of the most intriguing, undulating melodies I've ever heard. How long were you together? Do you still work with those other musicians? Finally, how would you describe that song? SB: Boneyard was my first original collaborative band. Joe was kind of inspirational. He had a funky swinging guitar and vocal style. The band was together on and off throughout the 1970s. It was very loose. Basically it was Joe, myself, and whoever decided to show up for the gig. We used to play around the North Jersey, NYC area. The partnership was musically influential and I began to take music and songwriting seriously - at least take a shot. Once we packed up and drove out west. We had a gig at a funky little bar in Flagstaff. Most of the clientele were black folks, except for two white guys who sat at the back of the bar. People were up dancing and we were feeling pretty good about our first gig out west. During the break we went out to the parking lot. Someone lit up a joint and surprise! The two white guys were narcs. They took the drummer away to jail and that was the end of that. We later reformed back in New Jersey. We were so naïve - a gang of scruffy hippies pulling into a small western town, driving crusty old jalopies with Jersey plates, making a lot of noise at a black bar in 1973. I'd say we'd served as easy marks for the narco squad. The mid sixties, early 1970s was a great time to be young and to be involved in a creative band. The period was probably one of the most fertile periods for pop music. There were so many styles to draw from. Speaking of things to draw from, ‘Got to Believe It’ sounds a bit like ‘If It Don't Work Out’ at times. Songwriting is a tricky business. You may come up with something that strikes a familiar chord. You could never be too sure if it's a universal chord or you've unwittingly ripped it off from another song that you may have heard somewhere along the line. It’s been quite some time since I played with Joe and Walter just because of the geographical distance. How would I describe, ‘Got to Believe it?’ It’s sort of a funky, grooving feel-good song. There wasn’t a drummer in the video, but the groove held up in the instruments and voices. The video was shot seven years after the Arizona escapade. I hope the drummer wasn’t still rotting in some jail out west. PB: ‘Scattered Tracks’ consists of 15 songs. Is there a characteristic that binds them together? Can you elaborate on this project and tell us which songs seem to attract the most attention, and why? Finally, if I didn't know your work and had time to listen to just a few tracks, which would you recommend? SB: ‘Scattered Tracks’ is a collection of demos that were recorded between the mid1980s and 2002. Some of the tracks are pop songs and some of them are short, instrumental pieces that were meant to serve as a demo for film sound tracks. I enjoy doing instrumentals. It frees up the confines of the pop tune structure, plus I don't have to bother with the chore of lyrics. I don't do orchestral arrangements but I'll take little bits from ‘Firebird’ or ‘West Side Story’ and apply it to my little guitar, harmonica, piano world. Stravinsky would sometimes use simple Russian folk melodies to apply to his high art. I guess it could go both ways. I kind of liked Elmer Bernstein’s soundtracks. He did the music to ‘Some Came Running’ and ‘Man with a Golden Arm’, among others. A journalist friend interviewed Elmer Bernstein around the time that I made those demos. When the interview was finished, she played a track for him to listen to. He said something positive about it and then he said, "Could you play that again?" The interview tape was still going, so she called me up and played it for me. It's nice to get a nod from the teacher. One of the tracks ‘Bliss Kiss’ was used in a doc called ‘Tootie’s Last Suit’. People seem to like ‘Pretty Poison’ and ‘Beat Angels’. A radio disc jockey in Florida was playing ‘Tender Touch’ a lot. ‘Live It Up Time’ is somewhere between ‘West Side Story’ and the Mississippi Delta. There is a short track called ‘Rues and Avenues’.I play two harmonicas of different keys at the same time. Coupling two harmonicas of different keys can produce a cool cluster of sound. Some of the soundtracks are short because I was told that film demos shouldn't waste too much time. In the mid-1990s, I was signed to a publishing company. Most of the songs are from those demos. They were meant for someone else to sing, but for better or for worse, it's my voice on the recordings I just thought I would gather them up and put it there on CD Baby. We don't have CDs printed up; it’s just MP3 download. PB: You co-wrote 'Phantom of the Footlights', which appeared on guitarist Buzz Feiten and keyboardist Niels Larsen's 1982 album, ‘Full Moon’. Niels and Buzz also played on Rickie Lee Jones' eponymous debut album. It's a catchy, upbeat song with sophisticated changes and a riveting theme. Some people say it brings to mind Steely Dan. What kind of style were you going for? What do you remember about recording the song in the studio? SB: “If I remember correctly, Buzz and the band had already laid down the basic music track. It needed voice and lyrics. I started singing some be bop over it. We worked up some lyrics. I think Buzz went into the studio the next week or so and laid down the vocal track. It does have that Steely Day sound to it. The horns may have a lot to do with it. The LA studio sound of the day is prevalent. Walter Becker produced and played bass on ‘Flying Cowboys’. Maybe there was some sort of thread happening there on some level. PB: How do you see yourself spending the next five years? SB: Alive and well, I hope. Playing some good music, somewhere. PB: Thank you. The fourth photo that accompanies this article was taken by Philamonjaro at www.philamonjaro.com,

Picture Gallery:-

Visitor Comments:- |

| 891 Posted By: Dawn Ducoulombier, dawnduco@gmail.com on 17 May 2019 |

|

You are the part of the magic behind Rickie Lee Jones. I always imagined who you were, Sal Bernardi, you are still mysterious voice, yet one I recognize. Please keep singing. Your tempo, style, sound is so comforting to me. I can hear your sound and influence in RLJ's music. Thank you.

|

| 823 Posted By: Pat woods, Corvallis oregon USA on 04 Apr 2017 |

|

Fun to read how sal has not changed

|

intro

Lisa Torem speaks to Paris-based singer-songwriter Sal Bernardi about his lengthy musical partnership with Rickie Lee jones and his own solo career

most viewed articles

current edition

Carl Ewens - David Bowie 1964 to 1982 On Track: Every Album, Every SongArmory Show - Interview with Richard Jobson

John McKay - Interview

Colin Blunstone - Thalia Hall, Chicago, 16/7/2025

Bathers - Photoscapes 1

Billie Eilish - O2 Arena, London, 10/7/2025

Loft - Interview

Visor Fest - Valencia, Spain, 26/9/2025...27/9/2025

Sir Tim Rice - Interview

Robert Forster - Interview

previous editions

Manic Street Preachers - (Gig of a Lifetime) Millennium Stadium, Cardiff, December 1999Heavenly - P.U.N.K. Girl EP

Beautiful South - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

Peter Perrett - In Dreams Begin Responsibilities Interview Part One

Boomtown Rats - Ten Songs That Made Me Love....

Oasis - Oasis, Earl's Court, London, 1995

Coldplay - Wembley Arena. London, 16/8/2022

Prolapse - Interview

Trudie Myerscough-Harris - Interview

Pixies - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

most viewed reviews

current edition

Davey Woodward - Mumbo in the JumboSick Man of Europe - The Sick Man of Europe

Lucy Spraggan - Other Sides of the Moon

Amy Macdonald - Is This What You've Been Waiting For?

Suzanne Vega - Flying With Angels

Blueboy - 2

Bush - I Beat Loneliness

Phew, Erika Kobayashi,, Dieter Moebius - Radium Girls

Alice Cooper - The Revenge of Alice Cooper

Cynthia Erivo - I Forgive You

Pennyblackmusic Regular Contributors

Adrian Janes

Amanda J. Window

Andrew Twambley

Anthony Dhanendran

Benjamin Howarth

Cila Warncke

Daniel Cressey

Darren Aston

Dastardly

Dave Goodwin

Denzil Watson

Dominic B. Simpson

Eoghan Lyng

Fiona Hutchings

Harry Sherriff

Helen Tipping

Jamie Rowland

John Clarkson

Julie Cruickshank

Kimberly Bright

Lisa Torem

Maarten Schiethart