Velvet Underground - Velvet Underground Part 3

by Jon Rogers

published: 27 / 8 / 2012

intro

With Nico having become a reluctant member of the band, Jon Rogers in the third part of his series on the Velvet Underground reflects on their Exploding Plastic Inevitable residency in New York, and recording continuing on their influential debut album, 'The Velvet Underground and Nico'

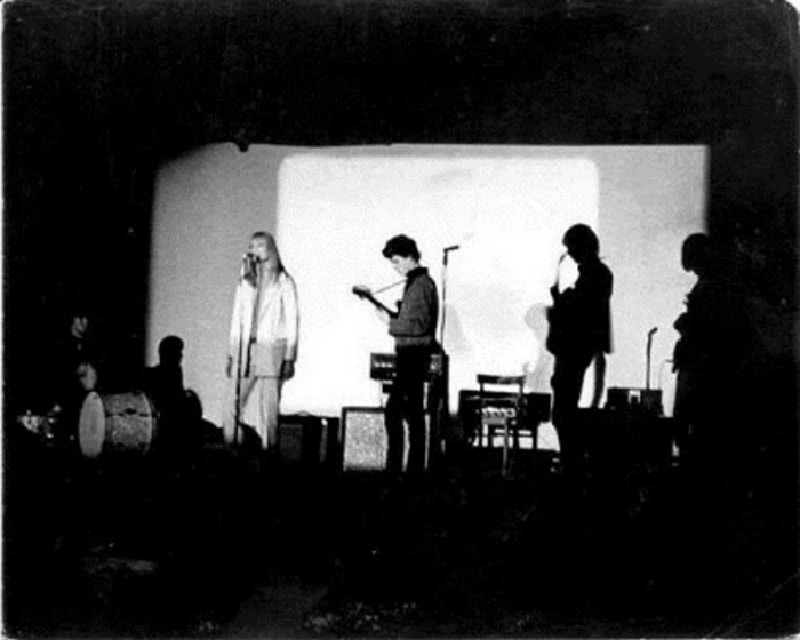

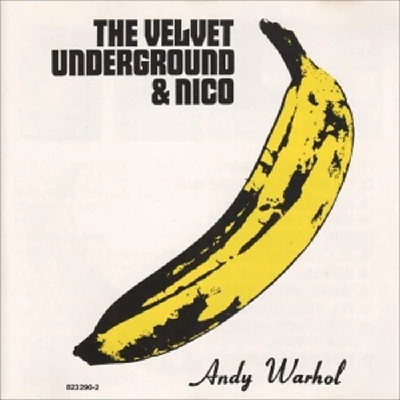

It is around now that the band start playing gigs as part of an "event" centred around Andy Warhol and his films and which is billed as 'Up-Tight with Andy Warhol' which features strobe lighting, Warhol's films being projected onto the walls and the band playing at loud volumes. It's a multimedia event that will eventually evolve into the Exploding Plastic Inevitable when the band start their residency on 1st April at the Dom - short for Polski Dom Narodwy (Polish National Home) - at 23 St Mark's Place. The venue was only booked at the last minute after a deal Morrissey had been working on for the band to play a place in Queens fell through after another band was picked. A deal was struck between Morrissey and the owner of the Dom Stanley Tolkin on 28th March with the band's first gig on 1st April with a lease being taken out for the entire month and an ad being placed in the 'Village Voice' for the 31st March edition. Interestingly the ad states: "Come blow your mind. The silver dream factory presents the first Erupting Plastic Inevitable with Andy Warhol, the Velvet Underground and Nico." So perhaps the actual name wasn't even finalised by then. Nowadays the Velvet Underground at the Dom is the stuff of myth and legend, up there with the likes of the Doors at the Whiskey-A-Go-Go or the Beatles at the Cavern Club. And it would actually seem that the reality lived up to the myth. Projectors, sometimes worked by Warhol, would show films such as 'Kiss', 'Sleep', 'Blow Job' and 'Vinyl' up on two large film screens and different coloured blobs of gelatine would be put over the lenses. Strobe lights are used to give a disorientating effect, made worse by having their beams facing a spinning, glittering ball suspended from the ceiling in the middle of the hall. Gerard Malanga is joined on stage by the likes of Mary Woronov, Ingrid Superstar, Ronnie Cutrone and Eric Emerson as dancers. As Cutrone explains in Victor Bockris’ 'Up-Tight: the Story of the Velvet Underground': "The great thing about the Exploding Plastic Inevitable was that it left nothing to the imagination. We were on stage with bullwhips, giant flashlights, hypodermic needles, barbells, big wooden crosses... You were shocked because sometimes your imagination wasn't strong enough to imagine people shooting up on stage, being crucified and licking boots." Amongst all that there was the Velvet Underground all dressed in black, with black shades - all except Nico who would wear a white trouser suit - blasting out their songs about drug-taking and sado-masochism. According to Richie Unterberger the EPI shows are a commercial success from the very first day with 750 people coming along to the opening night and others being turned away. The entrance fee is $2 on a weekday and 50 cents more at the weekend. Apparently, the shows make $18,000 in the first week and garner plenty of press coverage straight away. The 'Village Voice' devotes an entire page to the spectacle and several pictures. While the New York Times gives over half a page in its fashion section but mainly focuses on the scenesters who show up and only makes passing reference to the band. More attention is given to Nico though who is quoted as saying: "Modelling is such a dull job. I don't care to get $60 an hour anymore." At one gig Tucker's drums are stolen and Reed suggests she finds some bins and puts mics under them, and so she ends up playing those for a few nights. Tucker recollected the event in a 1980 interview with New York Rocker: "At the end of the night we'd have to clean up little piles of garbage that got shook loose during the set." Some reviews do at least pay some attention to the band with the East Village Other stating: "Twice during the evening were sets by the Velvet Underground, a group whose howling, throbbing beat is amplified and extended by electronic dial-twiddling. It is a sound hard to describe, even harder to duplicate, but haunting in its uniqueness. And with the Velvets come the blonde, bland, beautiful Nico, another cooler Dietrich for another cooler generation... Art has come to the discotheque and it will never be the same again." Norman Dolph, who will play a large part in recording 'The Velvet Underground & Nico', operated the mobile disco which plays in between the band's sets and had Malanga carry around a 16mm projector, shooting images onto the audience, dancers and walls and remembers: "The music was clearly without precedent. I don't think I or anybody else had heard anything like it." The EPI also, thanks in part to the networking of Barbara Rubin, attracts some celebrities too. Showing up at one time or another are Salvador Dali, Robert Rauschenberg and Beat poet Allen Ginsberg, who according to his biographer Barry Miles, gets up on stage with the band and chants 'Hare Krishna'. As Cale reflects in an 1975 interview with 'Modern Hi-Fi and Music': "It was a show by and for freaks, of which there turned out to be many more than anyone had suspected, who finally had a place to go where they wouldn't be hassled and where they could have a good time." It's during their residency at The Dom that the band also enter a studio and record the bulk of what will become their debut album. Initially the idea was to record some songs as a way of shopping the band around to get a record deal, rather than to make a record itself and the costs of the studio time are shared between Warhol and Norman Dolph, who at the time was a Columbia Records sales executive and art collector and who had met Warhol through his side job of supplying music for art gallery opening and events with his mobile disco. Dolph worked in Columbia's Custom Labels division which provided services for smaller labels without their own pressing plant. Via one of the accounts he looks after, Scepter Records, he noticed that it had its own recording studio at 254 West 54th Street in New York - the address would later be home to the famous Studio 54 disco. So with Warhol leaving the details to Dolph around mid-April, possibly 18th, the band move over to Manhattan. "At no time was what we were doing ever referred to by anybody as a demo," recollects Dolph in Joe Harvard's 2004 book 'The Velvet Underground & Nico', which was part of the 33 1/3 series of publications by Continuum. "They were going for the jugular. They wanted to make a record that sounded like they sounded." In the book Dolph speculates that the recording takes place around sometime between 18th and 23rd and that the sessions amount to a total of four days; two days for recording, a third for listening to playbacks and a fourth for mixing with the studio costs amounting to between $2-3,000. Various estimates have been given as to just when, how long and how much the Scepter Studios recordings cost with even the members of the band unsure of the exact details. Dolph doesn't have any experience as a record producer and so brings in the house engineer, John Licata, to add some experienced professionalism. On the original release of the album neither Licata nor Dolph will get a mention, while Val Valentin is credited with being the engineer, although this will later be rectified on subsequent CD reissues. Licata is quoted by Unterberger as saying: "[Dolph] was wonderful, co-operative, easy to get along with... he was the total antithesis of the Velvet Underground. At no time did any of the musicians ever tell him what to do. They went in and played, and he got what they wanted. On the 'banana' album, they credit Val Valentin with the engineering. He may have done much of the remix or whatever, but he's certainly not the engineer that was responsible for the sound of the album at its basis. When I heard the album [a year later], it sounded to me just like what we did. It didn't sound appreciably different from what we did at Scepter." One of the reasons why the recording costs might have been so low was because of the actual state of Scepter Studios. According to Cale's autobiography the place is on the verge of being condemned: "We went in there and found that the floorboards were torn up, the walls were out, there were only four mics working. We set up the drums where there was enough floor, turned it all up, and went from there. Dolph ran the sessions, but he didn't understand the first thing about recording." Dolph freely admits he wasn't the producer in a conventional sense but described his role to Harvard: "I was not the producer in any sense that Quincy Jones is a producer. The only thing I would say is because they were doing it on my money, and we had limited time resources fiscally - 'cause we were always bumping up against commitments that Scepter had in the studio - I kept the thing on the rails. I think part of the way the record sounds is because of John and I keeping the damned thing going and moving. That's my contribution as a producer." What has provided endless debate about the album is the question of what exactly was Warhol's role in the making of the album. He is after all, named as the producer on the album. Clearly he wasn't the producer in any conventional sense of a record producer. He certainly lacked any technical knowledge of what to do and by all accounts wasn't there in the studio all the time and when he was, he didn't say much. According to Dolph, Warhol was merely a "spectator", only turning up occasionally to the studio. Then in would refrain from passing any sort of aesthetic judgement apart from the occasional "Gee, that sounds great." But certainly Warhol's presence is felt on the record, with Morrison telling 'Fusion' magazine in 1970 that he compared Warhol's role to that of a film producer, in the sense that he helped finance the sessions and generally looked after the band and madeg sure they were ok to enter the studio in the first place. Later, in an interview in 1986 with Ignacio Julià Morrison stated: "His [Warhol's] main contribution was to give us confidence." Reed, in a 1989 interview with 'Rolling Stone', when asked by David Fricke what exactly Warhol's role was, replied: "By keeping people away from us, because they thought he was producing it. They didn't sign us because of us. We were signed because of Andy. And he took all the flak. We said, 'He's the producer,' and he just sat there." In the 'Transformer' documentary, Reed praises Warhol: "What he did do is he made it all possible. One by his backing. And two, before we went in the studio he said, 'You've got to make sure - use all the dirty words. And don't let them clean things.' And so, when he was there, they, you know, they didn't dare try to say, 'Hey, why don't you do that over'." Who "they" Reed is referring to is rather unsure as at the time the band didn't have any sort of record company interest, let alone a recording deal, so who "they" were who might have tried to smooth out some of the "dirty words" is unclear. For a record that would later be seen to be pushing the boundaries of what was sonically possible on a rock record and lyrically would challenge orthodox notions of what a song should be about it was recorded in an extremely rudimentary way. According to Dolph, much of the record was recorded 'as live'; instead of each instrument being recorded separately the band, effectively, set up and played together, as if in a live setting: "You would normally expect if they were going to play that loud, they would be in a much larger room to get some isolation between one and the other. But there could have been little separation or isolation in any kind of modern sense in that room, considering how loud they were playing. The adrenaline quality of it was because we knew we had eight hours, and they wanted to get on with it, and I wanted to get on with it." Another factor was the financial restrictions. There simply wasn't the money available to buy more studio time or pay for more experienced knowledge. Apparently, there are no outtakes or fumbled attempts at takes on tape because with the tape cost at around $125 a roll if the band made any mistakes the tape was backed up and recorded over in an attempt to keep the cost down. According to Dolph though the band knew exactly what they wanted to do: "I don't know that anybody really told Lou Reed what to do or what they thought, but you got the feeling that musical decisions were being made largely by John Cale, sort of in conference with Sterling. Moe was very quiet in the whole thing. I don't think I heard her speak 10 words. [...] You had the impression that John was a studied, learned musician in the sense that he could read scores and all that sort of thing. Lou Reed was essentially a performer. I don't mean that derogatorily, but that he was the Mick Jagger of the deal, whereas John Cale was the Keith Richards of the deal." Dolph's role really seems to be the person who pressed the record button when necessary and kept an attentive ear out for any obvious mistakes or something that wasn't mixed correctly. In 'The Velvet Underground Under Review' documentary Tucker suggests that the limited time was a benefit: "[It] affected the process or the result favourably because we didn't have time for nonsense." And according to Dolph in the same documentary there was none of the usual comments of, "We'll fix that in the mix" or "I don't know. I'll play it back tomorrow. They just sung the songs live. Cale though wasn't happy with the recording process, calling it "a complete shambles" in the liner notes to 'Peel Slowly and See', the band's 1995 retrospective box set. "Norman Dolph is in the booth making comments like 'Great! Dynamite! We got it!' And we're all looking at each other, going 'Where is it written that he gets to say 'This is a take?'" In his autobiography though Cale is more upbeat and positive, revealing: "We were really excited. We had this opportunity to do something revolutionary - to combine the avant-garde and rock and roll, to do something symphonic. No matter how borderline destructive everything was, there was real excitement there for all of us. We just started playing and held it to the wall. I mean, we had a good time." The big problem appears not to be just how best to record the band to get a good enough recording but contention seems to arise over the question of just how many - if any - songs Nico should be allowed to sing. In one corner was Reed who didn't want Nico to appear at all on any songs. In the other was Morrissey who wanted her to be the featured vocalist on the album. In Richard Witts’ 1999 book 'Nico: the Life and Lies of an Icon', Paul Morrissey is quoted as saying: "Lou didn't want Nico to sing at all. I'd say, 'But Nico sings that song on stage,' and he'd reply, 'Well, it's my song.' Like it was his family. He was so petty." In the end the band will follow the standard set in their live shows, with Reed handling most of the singing and with Nico taking on the three songs she performed live - 'I'll Be Your Mirror', 'All Tomorrow's Parties' and 'Femme Fatale'. According to Morrissey, Nico had been pushing to take on the vocals of some of Reed's harsher songs, like 'Heroin' and 'I'm Waiting for the Man', songs even Morrissey admits Nico's voice wasn't suited for, especially when she kept on wanting to sing like Bob Dylan. And even then Nico struggled over getting the vocal delivery for 'I'll Be Your Mirror' right and keeps breaking down in tears between takes as she can't get it right. "At that point we said, 'Oh, try it one more time and then fuck it'," recalled Morrison to the 'NME' in 1981. Fortunately, the very next take saw Nico get it right. While much has been made of the friction between the band, especially Reed, and Nico over the years, Dolph noted that she was "treated with great respect" during the sessions. "Imagine Les Brown and his band of renown, and Doris Day as their singer. It's as though when Doris Day came on, she was a special focus of what that orchestra did." According to him, "It was in no way slapdash or quick or 'let's get this broad out of here.' Things went into sort of a quiet mode when she was there. I don't believe she was in the studio much longer than when she was performing in the studio." Along with the three Nico-sung songs recorded at Scepter were 'Run Run Run', 'The Black Angel's Death Song' (or as it was known at the time of recording as 'The Black Angel of Death') and 'European Son'. These songs, especially the last two, mark a sharp contrast from the more orthodox and melodic-sounding songs sung by Nico. 'The Black Angel's Death Song' sees Reed recite the surreal, stream-of consciousness lyrics as if inspired by his Beat Generation heroes and Dylan. They don't make any literal sense, but images are rapidly piled up on top of one another: "Sacrificials remains make it hard to forget Where you come from The stools of your eyes Serve to realise fame, choose again And Roberman's refrain of the sacrilege recluse For the loss of a horse Went the bowels and a tail of a rat Come again, choose to go." But the most radical recording made at Scepter is what will be the closing song on the finished album - 'European Son', dedicated to Reed's old university lecturer Delmore Schwartz. The dedication was done with Reed's tongue firmly in his cheek as Morrison will later explain that Schwartz despised rock 'n' roll lyrics: "He thought they were ridiculous and awful and 'European Son' has hardly any lyrics so that meant that was a song that Delmore might like. He didn't care about the music part of rock 'n' roll, he just hated the lyrics, so we wrote a song that Delmore would like: 20 seconds of lyrics and seven minutes of noise." The song starts off normally enough, an innocuous enough guitar refrain in the Bo Diddley vein gets things going, then Reed chips in with two verses of abstract lyrics that don't make any logical sense and are delivered with a snarl. Then after a crashing sound barely a minute in the band launch into what is little more than structured noise/jamming. Guitars collide and crash about and get swamped in distortion. Tucker's drumming is irregular and rise and fall when the moment takes her and it all ends in dissonance. Interestingly enough 'European Son' fittingly closes the finished album in a sort of defiant 'you won't forget us' statement. But when the acetate is cut of these recordings it will be the very first track on the first side. Any record company executive who might be interested in singing the band will be hit full in the face by this from the off. And too, supposedly the acetate version is roughly a minute longer than the version on the finished album with supposedly even more chaotic guitar thrash being cut out immediately after the crashing sound. That crashing sound, according to Tucker, is made by Cale dragging a chair across the floor of the studio and then dropping either a glass or bottle after stopping in front of Reed. Martha Morrison - then Sterling's girlfriend and later wife – however, recollects the crashing sound was actually made by Reed by dropping a mirror to replicate the sound of breaking glass. Martha claims to have got hysterical and got shouted by Reed. "I just thought it was a riot, what they were doing to get their sound effects. I wasn't serious enough." According to Norman Dolph, 'There She Goes Again' was also recorded at Scepter Studios but doesn't appear on the acetate but does contain three other songs recorded there - 'Heroin', 'I'm Waiting for The Man' and 'Venus in Furs' but these versions won't make the final album cut despite there being only really minor changes from the versions made here and the ones included on the album. The result of cutting the acetate has mixed blessings, in one way it was a failure as it didn't result in getting the band a recording deal - although one is forthcoming with Verve/MGM down the line and it will be nearly a year later when the album finally gets to see the light of day. It is at these sessions, however, that the bulk of what is seen now as a classic album is recorded (albeit with minor alterations) and what is recorded here is now undoubtedly seen as an artistic triumph. There is also some speculation that other songs may have also been recorded at Scepter as a number of songs are registered with the Library of Congress on 22 April 1966. Along with the songs on the acetate and Reed/Cale composition called 'Get It On Time' is also registered as well as the ballad 'Little Sister' (which will appear on Nico's debut solo album 'Chelsea Girl') and 'Wrap Your Troubles in Dreams'. The most obvious record company to approach first for a deal is Columbia, due to Dolph's connections with his day job as a sales executive but got a swift rejection letter back saying: "There is no way in the world any sane person would buy or want to listen or put anything behind this record." Similar rejections came from Atlantic and Elektra, the latter, Morrison recollected later to the 'NME', found the "content and sound unacceptable. This viola - can't Cale play anything else?" One person who did show some interest was Columbia's in-house producer Tom Wilson, famed for his work with Dylan on 'Like a Rolling Stone' and Simon and Garfunkel's 'Sound of Silence'. But there was a delay as Wilson was in the process of leaving Columbia to go and work with MGM where he was going to set up a rock division of the Verve label which had built up a name for itself with its jazz releases. The only other rock act on the label would be Frank Zappa's group the Mothers of Invention. "[Wilson] told us to wait and come and sign with him," Morrison told the 'NME' in 1981. "When he moved to Verve because he swore that at Verve we could do anything we wanted. And he was right." But the deciding factor swaying Wilson was, according to Morrissey, Nico. "He [Wilson] said, 'I'm interested in recording them, I went to see them. I can't put any of this on the radio but that girl [Nico] is fantastic. She could be a big star, and I'll sign the whole group just to have Nico.' Well, when I went back I made the mistake of telling that to Lou, and he really froze. The last thing in the world that he wanted to hear was this album was only being taken on because of beautiful Nico with the beautiful voice, and that Tom Wilson really wanted her, not them. Even Reed would accept that Nico's looks - as well as the figure of Warhol - helped the band get a contract with MGM. In the BBC Wales documentary 'John Cale' Reed says: "We finally were signed to a record company, really on the basis of Andy. Because Andy said he'd do the cover [of the album]. I don't know if we would have gotten a contract if he hadn't said he'd do the cover, or if Nico wasn't so beautiful... for the longest time, people thought Andy Warhol was the guitar player!"

profiles |

|

White Light / White Heat, Part 3 (2014) |

|

| In the final part of his three part series on the Velvet Underground's 1968 second LP 'White Light/White Heat', Jon Rogers examines critical perception of it since its release and its recent box set |

| White Light/White Heat Part 2 (2014) |

| White Light/White Heat Part 1 (2014) |

| Velvet Underground Part 4 (2012) |

| Velvet Underground Part 5 (2012) |

| Velvet Underground Part 1 (2012) |

| Velvet Underground Part 2 (2012) |

favourite album |

|

The Velvet Underground and Nico (2012) |

|

| Dominic Simpson, in our 'Re View' column, in which writers look back at albums from the past, reflects on the Velvet Underground's classic 1967 debut album with Nico |

| Velvet Underground and Nico (2002) |

most viewed articles

current edition

Spear Of Destiny - InterviewRobert Forster - Interview

Fiona Hutchings - Interview

When Rivers Meet - Waterfront, Norwich, 29/5/2025

Carl Ewens - David Bowie 1964 to 1982 On Track: Every Album, Every Song

Brian Wilson - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

Pistol Daisys - Waterfront, Norwich, 29/5/2025

Nils Petter Molvaer - El Molino, Barcelona, 24/4/2025

Skunk Anansie - Old Market, Brighton, 16/5/2025

Credits - ARC, Liverpool, 17/5.2025

previous editions

Heavenly - P.U.N.K. Girl EPOasis - Oasis, Earl's Court, London, 1995

Boomtown Rats - Ten Songs That Made Me Love....

Dwina Gibb - Interview

Trudie Myerscough-Harris - Interview

Sound - Interview with Bi Marshall Part 1

Serge Gainsbourg - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

Susie Hug - Interview

Brad Elvis - Interview

Chuck Prophet - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

most viewed reviews

current edition

Peter Doolan - I Am a Tree Rooted to the Spot and a Snake Moves Around Me,in a CircleGarbage - Let All That We Imagine Be The Light

John McKay - Sixes and #Sevens

Suzanne Vega - Flying With Angels

Little Simz - Lotus

Vinny Peculiar - Things Too Long Left Unsaid

Billy Nomates - Metalhorse

Eddie Chacon - Lay Low

Only Child - Holy Ghosts

Vultures - Liz Kershaw Session 16.06.88

Pennyblackmusic Regular Contributors

Adrian Janes

Amanda J. Window

Andrew Twambley

Anthony Dhanendran

Benjamin Howarth

Cila Warncke

Daniel Cressey

Darren Aston

Dastardly

Dave Goodwin

Denzil Watson

Dominic B. Simpson

Eoghan Lyng

Fiona Hutchings

Harry Sherriff

Helen Tipping

Jamie Rowland

John Clarkson

Julie Cruickshank

Kimberly Bright

Lisa Torem

Maarten Schiethart