Outsiders - Outsiders

by John Clarkson

published: 23 / 6 / 2012

intro

John Clarkson looks back on the career of 70's band the Outsiders, which was the first group of Adrian Borland from the Sound, and who are often seen as being the the first punk band to self-release an album

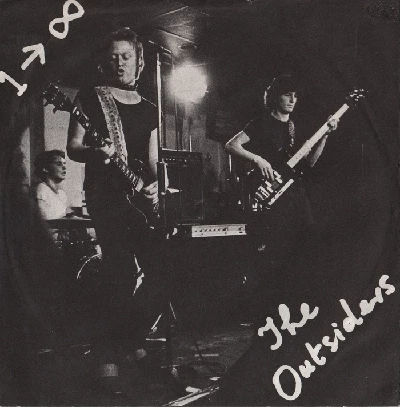

The Outsiders, whose two albums 1977’s ‘Calling On Youth’ and 1978’s ‘Close Up’ have recently been released on CD for the first time, are of musical interest for two reasons. They were the first group of the London-based singer-songwriter Adrian Borland, whose next band the Sound have gone through a revival of fortunes and attention since his early death at the age of 41 in 1999. They are also often seen as being the first punk band with ‘Calling On Youth’to self-release an album. The group was formed in South London under its original name of Syndrome in February 1973 when Borland, who was the middle class only son of a Wimbledon physicist and English teacher, was fifteen. Syndrome went through various permutations, including involving an on-off keyboardist for its first two years. Borland also dabbled for a while in playing in another group, the BB Band, which also featured Steve Budd, who would go on to manage the Sound between 1979 and 1982, and that got as far as playing five gigs before splitting up in 1975. By 1975, Syndrome had settled on its permanent line-up of Borland (guitar and vocals), and his school friends Adrian ‘Jan ‘ Janes (drums), who joined the group in April 1973, and Bob Lawrence (bass), who became a member in early 1974. The group’s name change came in 1976 when Janes, the band’s main lyricist, discovered that a number of bands, such as, for example, the Doors (with Aldous Huxley’s ‘The Doors of Perception’), had taken their names from literary sources. The Outsiders’ name was adapted from Albert Camus’s 1942 first novel, ‘The Outsider’, which, despite being about existential alienation, a theme which would become common for the Outsiders, Janes would not actually read until a year later. “He was always a true enthusiast for music, whether in the keenness with which from the start he created his own, or as a fan of others,” said Janes about Adrian Borland in ‘Book of (Happy)Memories’, a collection of reminiscences from family and friends that was published by a Dutch fan Willemien Spook in 2000 a year after his death. “While still at school, in the early days of the Outsiders, his guitar rarely left his hands during a rehearsal. He would strum it and keep it slung around his neck even during breaks for food.” The Outsiders struggled at first both to find gigs or a record label. Virgin Records took an option out on them, and paid for the recording of two tracks, ‘Hit and Run’ and the title track of what became their first album, ‘Calling on Youth’, at Pathway Studios in Islington in North London. When a deal, however, failed to materialise, the Outsiders took the then unprecedented step of self-recording an album at Borland’s home, with his father, Bob, serving as an engineer. Bob Borland and his wife Win were supportive of their son’s musical ambitions, allowing the group to initially rehearse in the family home, and then both financing the recording of the album and also setting up a record label, Raw Edge Recordings, to release it. “As far as we were concerned, that’s what Adrian wanted to do. It was a case of helping,” Bob Borland told music journalist Keiron Tyler at online magazine The Arts Desk www.theartsdesk.com in an interview earlier this year. “He loved Patti Smith and the Velvet Underground. Adrian regarded himself as a punk at the time. He frequented the 100 Club and was very keen on Johnny Rotten. In one of the clips you see of the Sex Pistols on TV, you see him pogoing up and down. Adrian would often come in late at night and play the Stooges’ ‘Raw Power’. He had headphones, but played it so loud he’d wake us up." Bob Borland worked for the National Physical Laboratory, setting standards for weights, measures and temperature calibration, and from there it was a short step upwards for him to learn about the rudiments of recording. “I went to an audio shop in Tottenham Court Road,” he recalled in the same interview. “And got some good advice from a knowledgeable salesman … on how to set up a relatively inexpensive recording facility.” ‘Calling On Youth’ was recorded over two sessions at the Borlands’ home, one in the summer of 1976 and the other in early 1977, with the band playing downstairs in the living room, while Bob Borland upstairs in his study operated both a four track tape recorder and a mixing desk. “I don’t think that we thought of it that way at the time,” Bob Borland told ‘Record Collector’ journalist Tim Peacock in an interview for the sleeve notes that accompany its reissue when asked if he saw it as the first self-released punk album. “I just thought of it as ‘the fourtht punk album” to be released (after the Ramones, the Damned and the Clash). The adjective ‘independent’ as a label had no particular meaning to me. However although we were not the first to release a punk album, I believe that we were the first to start recording an album.” ‘Calling On Youth’, which came out in May 1977, was distributed through the first Rough Trade shop, which had opened a few months before in Notting Hill in London, and Caroline Exports in the States. “There is a story that has been perpetuated that the Outsiders were the first band to self-release an album,” Bob Borland also revealed to Tim Peacock.” That is slightly misleading in the fact that Win and myself, as Raw Edge Records, were formerly independent of the Outsiders. We had an agreement with them whereby we paid all the costs of recording and agreed to pay them a percentage of gross sales.” “Adrian did a lot of unpaid work for Raw Edge, and it was he who made the first approach to Geoff Travis of Rough Trade…. Adrian designed the cover for ‘Calling on Youth’, and it was Adrian who suggested the name ‘Raw Edge’. We did not recover all our costs, but we did recover a much greater percentage than I had initially expected.” ‘Calling On Youth’ was, however, panned on its release by the critics. The group had played its debut gig supporting Generation X a few months earlier at the legendary punk club The Roxy on the 14th December 1977, and had fallen foul of the notoriously vitriolic Julie Burchill when they played a second gig there five weeks later on January 21st. “At closer examination they are mediocrity personified, but they are about as New Wave as the Grateful Dead,” she wrote in her paper ‘NME’. Her review of ‘Calling On Youth’ was even more scathing. “I went to school with chicks who were more bad-ass than these boys,” Burchill sneered, before adding: “The Outsiders play as competently as any 19 year olds whose parents were rich enough to buy them electric toys last Christmas. The album is produced as nicely as would be any album put out on a label set up especially by the rich Daddies. But I’m just so BORED with these well-bred little students toying with our music like it’s the latest coffee-table conversation piece. I’m so sick of rich bitches hooking their claws into our cause. I’m so tired of people who need to think about breathing.” Unfortunately another review from Jon Savage in ‘Sounds’, while slightly more constructive in its criticism, was similarly damning. “I wish they’d waited until they’d gained a whole lot more experience because an album is terribly premature,” Savage, who would go on to write the seminal 1991 punk book ‘England’s Dreaming’, would say. “The playing’s OK... but the lyrics generally are too full of intensely personal teenage angst and empty of art. Yeah - I’ve no doubt Adrian Borland feels what he sings/writes, but the result is a mess of clichés adding up to embarrassment.... Still, I suppose it’s something to show people, and maybe they’ll get more gigs... it’s a start.” A lot of the bile that was directed towards the Outsiders centred from the fact that Borland, who wore his hair long and was slightly fat, did not fit into the punk prototype. There was also a terrible inverted snobbery going on, as prevailed much of the punk movement at the tme, because the Outsiders came from middle class Wimbledon rather than working class backgrounds. Burchill did, however, have a vague point with her remark about the Grateful Dead, as did Savage with his comment about a “mess of clichés”. Many of Janes’ lyrics for Borland on ‘Calling On Youth’ were fairly hackneyed. “I’m calling on youth to fight for the truth,” Borland yelled on the title track, and “I’m on the edge/You’re on the edge/We’re on the edge together” on ‘On the Edge’. A few of the tracks such as ‘On the Edge’ and ‘Weird’, with their long, meandering guitar work-outs, also skirted on the perimeters of prog and soft metal territory. Whatever its faults, however, ‘Calling On Youth’ stands up thirty five years on as an album that was far more complex than it was credited for at the time, and one which extended far beyond the then limited blueprints of punk. For every track of Stooges/James Williamson-style riffs (‘Calling On Youth’, ‘On the Edge’, ‘Hit and Run’ and ‘Terminal Case’), there was something else of a completely different nature. ‘Break Free’ was a lamenting, trebly ballad to a lost love, which carried a sudden, sharp spite. “I saw you a princess/Now I see you as a slut,” Borland crooned at its mid-point. The experimental ‘Start Over’ pushed Borland’s vocals down to a brooding murmur over which an acoustic, steady back beat gradually soared upwards. The album’s stand out track, the self-loathing and mocking ‘I’m Screwed Up’ (“Most of all I hate myself/I’m screwed up”) meanwhile merged together grinding guitar rhythms with a funk beat, while Borland’s vocals concluded it in torn howls of ‘Cold Turkey’-style despair. For all the backlash against them, the Outsiders were given a major boost in September of 1977, when one night at The Roxy they were joined on stage by Iggy Pop. The former Stooges vocalist was in town to play two shows at The Rainbow to promote his ‘Lust for Life’ album and visited The Roxy with ‘NME’ journalist Nick Kent. “For a joke I put Iggy and David Bowie on the guest list. Bowie didn’t turn up, but Iggy did!” Adrian Borland reminisced in a largely unpublished interview, part of which finally made its way into ‘Book of (Happy)Memories’. “I met him beforehand, but I was just dumbstruck. I mean, here was my hero…The time came for us to play and we started up ‘Raw Power’. Then Iggy jumps down the stairs, and does the second verse with us, and there’s all these cameras going off left, right and centre. It blew me away! I was 19. I was just gone.” Unfortunately, with the poor fortune that seemed to prevail the Outsiders, the evening concluded badly with Pop getting pulled away from the club after trying to fight a member of X-Ray Spex, and ‘Sounds’ misreporting the next week that he had jumped on stage with another Roxy band, the Psychos. ‘Sounds’ apologised in a later issue, printing a correction and also plugging the Outsiders’ first and only EP, ‘One to Infinity’, which came out in November. ‘One to Infinity’, which again was recorded at home by Bob Borland and became Raw Edge’s second release, however, met with further bad press. In its only review, NME’s Tony Parsons, who was then Julie Burchill’s boyfriend and eventually became briefly her husband, described it as “tuneless, gormless, gutless.” The title track was something of a dirge, and another track, ‘Consequences’ was similarly unmelodic, but the other two songs on ‘One to Infinity’ ranked amongst the Outsiders’ best material to date. ‘New Uniform’, a snappy Stooges-influenced number with ringing, abrasive guitars, found the Outsiders turning on their punk critics (“You’ve got to be one of the crowd to show that you don’t conform”). ‘Freeway’, a surreal Krautrock-influenced number, made early use of synthesisers and was even better still. Combining slowly reverberating sinister keyboards, doomy guitars and a funereal drumbeat, it was one of the few Outsiders numbers for which Borland rather than Adrian Janes had written the lyrics and found him taking a strange, self- hypnotising comfort in speeding fast on an empty motorway (“Freeway, free my dead end life.”). As 1977 moved into 1978, the Outsiders through the auspices of a new manager started to attract more gigs , other than just at The Roxy and London’s other punk club The Vortex where they had until now been largely confined. They played a residency in a pub The Man in the Moon, and also earned support slots at venues such as The 100 Club and The Marquee. At one show at The Speakeasy they also attracted their first positive review from Mick Mercer, who also wrote for the ‘NME’ , and concluded his piece by telling his audience that “maybe now Iggy’s said they’re “in the groove” many people (even Julie Burchill ) will catch on to them. They’ve got a lot of gigs soon, so go and see them.” The Outsiders’ second and final album, ‘Close Up’, which was recorded at Spaceward, a studio in Cambridge rather than the Borlands’ living room, and was the last release of Raw Edge, came out towards the end of 1978. The acoustic guitars and extended guitar solos of ‘Calling On Youth’ were gone. Adrian Janes’ lyrics, which were inspired in part by the abrupt minimalism of Kraftwerk, were also both much tighter and more mature. Although ‘Calling On Youth’ was a more diverse album that showed a group still trying to find its sound, ‘Close Up’, while at one level more monotone, revealed a band that had discovered its identity. The opening track, ‘Vital Hours’, was on the surface a brash, swaggering punk anthem, but its lyrics bubbled under with a sense of alienation and segregation from much of the rest of society (“I can forget the world that I go back to when I spend some vital hours with you.”). This was a theme that was developed across the remaining songs on ‘Close Up’, which swung between equally fast and furious punk numbers, and brooding and terse post-punk tracks. The waspish ‘Out of Place’ found the Outsiders paranoiacally out of alignment and detached from the world (“Like a crime that I didn’t commit/Yeah, accused I stand/Like a bill that I didn’t run up/Given the final demand”), while the jagged ‘Semi-Detached Life’ had them rebelling against the predictability and straightjacket boredom of their middle class backgrounds (“”Watching the soap opera/Washing a wearied mind clean/Same time next week, same channel/It’s a break from the routine”). The aching, mournful lament of ‘Keep the Pain Inside’ meanwhile smouldered with a tension and barely repressed hurt at rejection from a now ex-girlfriend (“Why can’t I become numb?”). ‘White Debt’, an atmospheric number of sinister-toned sound effects, turned over with palpitating horror the history and legacy of the British Empire (“Do you remember the days of empire?/Do you remember the days of horror?”), while the six minute ‘Conspiracy of War’, an anti-war number and precursor to Sound favourite ‘Missiles’ which two years later borrowed its beginning and close, brought the album to a dynamic and forceful close. Despite the group’s progression on this second album, ‘Close Up’ again met with negative reviews from the critics. The late Philip Hall, who would go on to manage the Manic Street Preachers, wrote in ‘Record Mirror’ that its songs were all “tuneless, messy efforts” and, while he conceded that Adrian Borland had a “fresh voice… he can’t save the second rate songs from scratching on the unfortunate listeners’ ears.” John Hamblett in ‘NME’ was more charitable, describing it as “a patchy, but promising collection of love songs and almost astute social documentaries”, and concluded by saying that he had a “few reservations”, but the Outsiders were “a band with a future.” The Outsiders were ironically, however, starting to fall apart. Bob Lawrence had announced that he planned to quit the band in mid-1978 even before recording on ‘Close Up’ began, and, while he stayed around long enough to record the album that summer, he left in the autumn of that year to go to university. He was replaced on bass by Graham Bailey, who was a neighbour and another old school friend of Adrian Borland’s. Bailey, who used the stage name of Graham Green, appeared on the sleeve of ‘Close Up’, and made his first live appearance with the Outsiders in November of that year. Shortly afterwards the group expanded to also include Bailey’s girlfriend Bi Marshall on clarinet. Marshall began by joining the band on stage at the end of their sets to play covers of ‘Louie Louie’ and the Stooges’ ‘TV Eye’ and ‘I Wanna be Your Dog’, before eventually becoming a full member in the autumn of 1979 when she obtained a synthesiser. The Outsiders played a short tour to promote ‘Close Up’ in April 1979 which would prove to be their swan song. When Adrian Janes announced his decision to leave the band in the autumn of that year to also go to university, he was replaced by Mike Dudley on drums and the group shortly afterwards changed its name to the Sound. Adrian Borland, having gained as confidence as a lyricist as well as a composer, and feeling that to sing with honesty he needed to articulate his feelings in his own words, wrote the majority of the lyrics to the Sound’s songs. Janes continued, however, to provide the occasional lyric, including ‘Words Fail Me’ and ‘Night Versus Day’, two of the songs which eventually merged on the Sound’s 1980 debut album ‘Jeopardy’, and both of which the pair had begun to work on during the Outsiders last year together. He also wrote the lyrics for two songs for Borland and Bailey’s side project Second Layer, ‘Germany’ for their 1979 debut EP, ‘Flesh as Property’, and the title track for their second EP, ‘State of Emergency’, which came out in 1980. The Sound recorded six albums with Colvin Mayers replacing Bi Marshall on keyboards after ‘Jeopardy’. After they split up in 1988, Adrian Borland began a solo career, and recorded five low-key albums. In the mid-1980s, perhaps in part precipitated by the Sound’s lack of commercial success, he started to display symptoms of an afflicted schizoid disorder. This meant that there were times in which he would temporarily lose touch with reality and suffer from hallucinations and hear voices. There were occasions in which he was sectioned and others in which he would attempt suicide. As he put the finishing touches to his last album, ‘Harmony and Destruction’, Adrian Borland became ill again. He died on the early morning of April 26th 1999 after throwing himself in front of a train at Wimbledon Station. The Outsiders will inevitably be of most interest to fans of the Sound. Much maligned at the time, both their albums are worthy of note, however, as they showcase a band that, while at one level embracing the punk movements, were also brave and defiant enough not to be pulled down by its limitations and restrictions and to push against them. ‘Calling On Youth’ (which includes the ‘One to Infinity’ EP) and ‘Close Up’ have both been reissued on Cherry Red Records.

Band Links:-

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Outsiders_(British_band)Picture Gallery:-

interviews |

|

Interview with Bob Lawrence (2021) |

|

| Bassist Bob Lawrence, in the second of two interviews with 70's group the Outsiders, talks to John Clarkson about his memories of the group and front man Adrian Borland, and their new five CD box, set ‘Count for Something'. |

| Interview with Adrian Janes (2021) |

| Interview (2012) |

most viewed articles

current edition

Carl Ewens - David Bowie 1964 to 1982 On Track: Every Album, Every SongArmory Show - Interview with Richard Jobson

Colin Blunstone - Thalia Hall, Chicago, 16/7/2025

Bathers - Photoscapes 1

Visor Fest - Valencia, Spain, 26/9/2025...27/9/2025

John McKay - Interview

Billie Eilish - O2 Arena, London, 10/7/2025

Robert Forster - Interview

Sir Tim Rice - Interview

Loft - Interview

previous editions

Heavenly - P.U.N.K. Girl EPManic Street Preachers - (Gig of a Lifetime) Millennium Stadium, Cardiff, December 1999

Beautiful South - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

Pixies - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

Oasis - Oasis, Earl's Court, London, 1995

Prolapse - Interview

Trudie Myerscough-Harris - Interview

Paul Clerehugh - Interview

Doris Brendel - Interview

Simon Heavisides - Destiny Stopped Screaming: The Life and Times of Adrian Borland

most viewed reviews

current edition

Sick Man of Europe - The Sick Man of EuropeLucy Spraggan - Other Sides of the Moon

Amy Macdonald - Is This What You've Been Waiting For?

Phew, Erika Kobayashi,, Dieter Moebius - Radium Girls

Davey Woodward - Mumbo in the Jumbo

Bush - I Beat Loneliness

Alice Cooper - The Revenge of Alice Cooper

Blueboy - 2

Cynthia Erivo - I Forgive You

Suzanne Vega - Flying With Angels

related articles |

|

Moon Under Water: Interview (2019 |

|

| John Clarkson speaks to Moon Under Water about their unusual beginnings after forming at an Adrian Borland tribute night, their memories of him and their plans for an album of original material. |

Pennyblackmusic Regular Contributors

Adrian Janes

Amanda J. Window

Andrew Twambley

Anthony Dhanendran

Benjamin Howarth

Cila Warncke

Daniel Cressey

Darren Aston

Dastardly

Dave Goodwin

Denzil Watson

Dominic B. Simpson

Eoghan Lyng

Fiona Hutchings

Harry Sherriff

Helen Tipping

Jamie Rowland

John Clarkson

Julie Cruickshank

Kimberly Bright

Lisa Torem

Maarten Schiethart