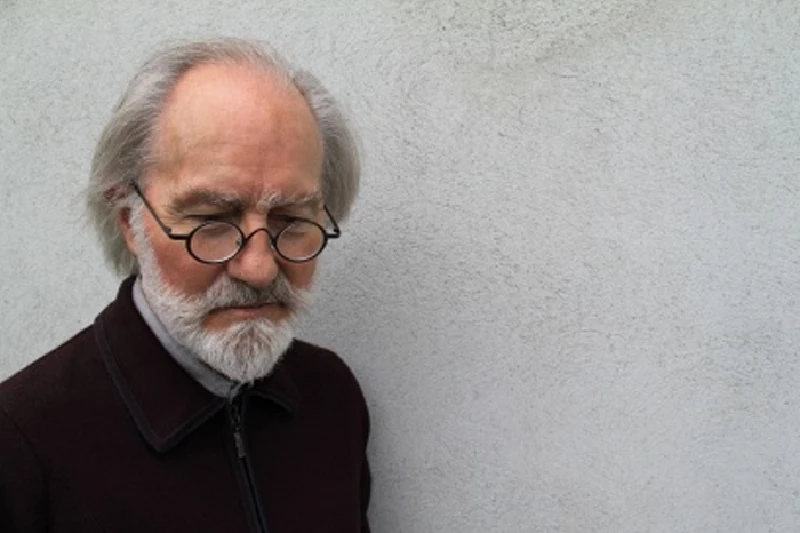

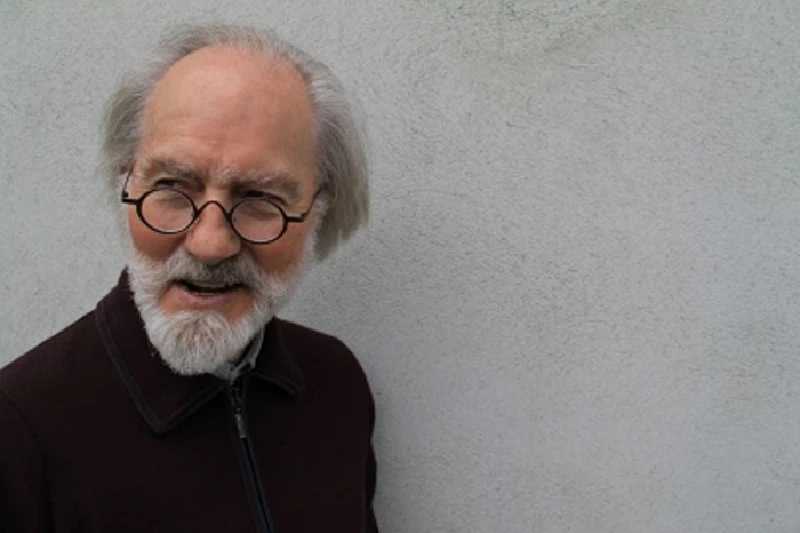

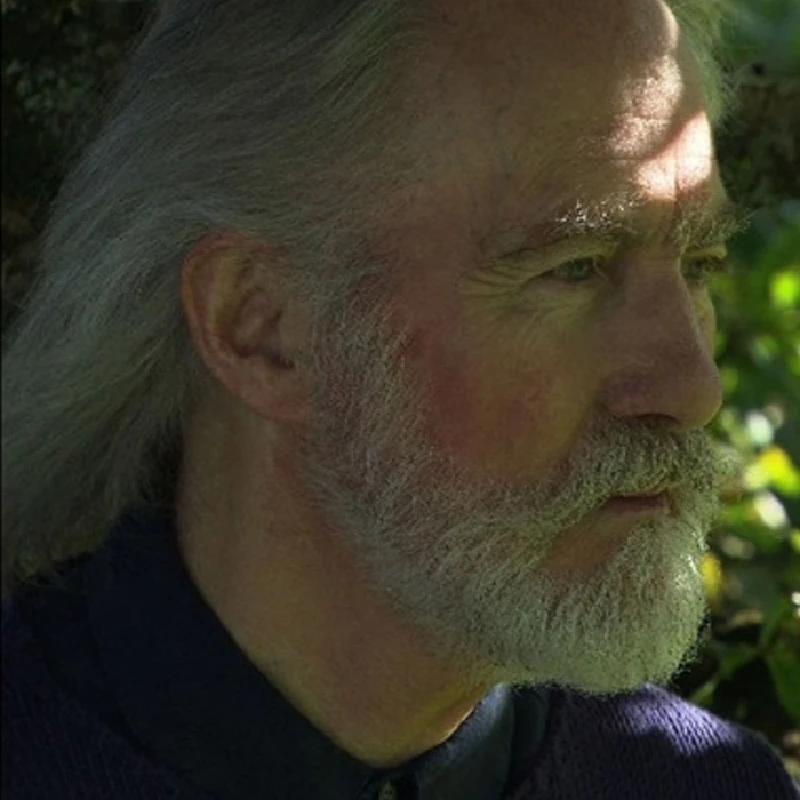

Roy Harper - Interview

by Benjamin Howarth

published: 20 / 7 / 2011

intro

Roy Harper speaks to Ben Howarth about the first four albums in the digital reissue series of his complete back catalogue, his 70th birthday and his plans for a new album

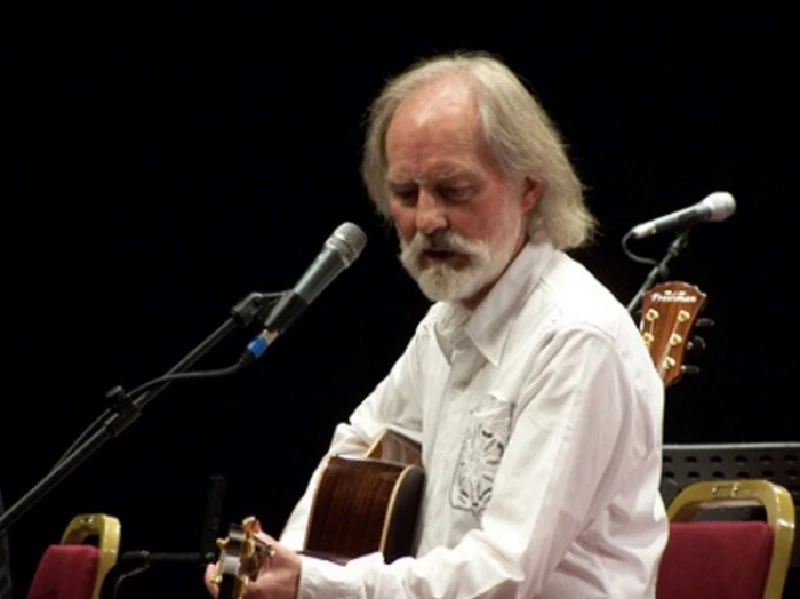

Roy Harper is best known for his connections to rock’s confirmed aristocracy. Led Zeppelin admired him so much that they ended their third album with a tribute, 'Hats Off to (Roy) Harper'. Pink Floyd had him singing lead vocals on their song 'Have a Cigar'. His own songwriting never attained a stadium sized fan base. Harper’s approach was an uncompromising mix of epic poems set to music and a style that never seemed to settle on either folk, blues, psychedelica or rock. If he has a signature tune, it is 'When An Old Cricketer Leaves the Crease'. John Peel loved it so much that he insisted it be played at his funeral. A simple acoustic strum, a wistful look at sunny days watching John Snow and Geoffrey Boycott, a brass band – only Paul McCartney has ever come as close to capturing the melancholy beauty of the English countryside in song. “I’m going to Lords tomorrow, and they’ve invited me to play it on Test Match Special,” he told Pennyblackmusic – at about the time Kevin Pietersen was beginning to lash the Indian outfield for his match-winning double century in the first test. “That’s going to be a special moment for me,” Harper went on. “That’s a brilliant song, and I really love it. It’s probably going to end up as my best known song, but who knows? There’s still some life in the old dog yet.” I was speaking to Roy in London. Now semi-retired, and living in Ireland, he was spending the middle of July in London, and had been at the Mojo awards the night before. Having carefully re-mastered his albums, which in recent years, have only been available through his own website, Harper is now readying his back catalogue for digital release. This begins with four of his best loved albums, but will eventually take in everything he has released. Those new to his music can start with a compilation, 'Songs Of Love and Loss', a selection of love songs – often overlooked when compared against his outspoken, epic songs. Roy spoke to Pennyblackmusic about the four albums that will come first in the reissue series, about his forthcoming 70th birthday show at the Royal Festival Hall and his plans for a new album. PB: What has prompted you to prepare your music for digital release, and release it on iTunes, especially given that you haven’t done it before? RH: It’s really just time that I did it. I was against it for years, but it suddenly occurred to me that the security was a lot better. I don’t have character lawyers. I can’t go in there blasting. So I’ve held off until now, until I feel safer. Now, the Chinese are even being pulled in. It may take decades, but they are in tacit agreement with the idea that intellectual property has worth... that you pay the artists at some point. PB: Have you followed any of the recent changes in intellectual law? There have been some tentative steps to actually have realistic sanctions for online copyright theft, with the potential to punish people and stop the downloading of things that people haven’t paid for. RH: It’s about time. Obviously it’s about time. I think intellectual property is incredibly important. When I was young, the music industry was crooked. It really was crooked. The kind of things that happened then surely can’t stand up in a court of law anymore. I was in my early twenties and I made my first record, I did it for 1.5% of dealer price, minus 15% for packaging and recording costs. Well, of course, packaging costs were never paid - and that was a passport to making no money at all. On my second and third records, the terms were slightly better, thankfully. But it has taken me until this time in my life, almost fifty years later, for me to start being able to claim back the royalties I’m entitled to with any authority. PB: I gather there are multiple formats of your debut album ('Sophisticated Beggar') available, only one of which you receive any personal benefit from. RH: What has happened is that, every time I appear in front of him, the owner of that particular record waves a piece of paper at my face, which is the proof that he bought it from the official receiver in 1970 for £50. That is truly ridiculous. That’s all the evidence that he’s got for claiming the royalties. I have a plan for the future... there are one thousand one jobs to do when you are running a small independent record label, but whenever we have any spare cash of note we’re going to take those guys to court. It will take several thousand pounds to do. You can’t do it for £500, I’ve tried that. All £500 gets is the lawyers in a room talking to each other. When the legal action goes a bit further, if we spend £5000-6000, then I think they will give in. It won’t qualify to go to court. It’ll be thrown out. So, I’m not saying that the music business was anything less than corrupt when I first knew it. It’s about time, in my estimation, that it wasn’t. PB: I couldn’t agree more. RH: But I feel more comfortable now with releasing music online. PB: Well, shall we talk about 'Sophisticated Beggar', which is the first of the four that you are re-releasing now. When it first came out, it wasn’t especially well distributed. Am I right? RH: Yes. Don’t forget, records in those days were like confetti. There were thousands and thousands made. They were dead cheap. No one thought about the environmental effects of making vinyl or the hyper-chemical costs of this. They just threw out as many as they could. Obviously thousands of copies were made – I suspect at least 20,000, although they still go on eBay for £70 sometimes. But there are enough of them around to indicate at least 20,000 were made. I think it’s a great record, that first one. PB: Was it a collection of everything you had written up to that point, or was it specifically designed as an album? RH: I was 23, coming on 24, at the time that album was recorded and actually released. Actually, I was older than that... It was sort of what I’d built up to. Mine was a strange journey, because I didn’t start out as a musician, although I did play blues on the streets as a teenager. But I started out interested in poetry. I came through from there, suddenly discovering at the age of 21 and 22 that I could be using my expertise - as it was at the time - on the guitar to put lyrics to. Poetry for me led me on to making music. It took me two to three years longer than my contemporaries to get there, because all I had been interested in was writing lyrics. So, 'Sophisticated Beggar' was a compendium of everything that had happened between 21 and 24. There were a lot of other songs recorded at the time as well, which didn’t get onto that record, and some of those came out on a much later release in the 2000s. It was mixture of all the things - the nuances as well - that would appear later on, on the other records. There were soft finger-picking guitar things, all the way to rock and roll songs. You couldn’t really pigeonhole me at that point. I got put in with the folk scene because that is what I could do. I could sit on stage with one guitar and make a living. But it was bad in a lot of ways. I got thrown out of a lot of the working men’s clubs in the north of England, for not singing the right kind of song – about mining or whatever. The kind of social commentary that I was into as a young man, they weren’t willing to take that. PB: Musically, you perhaps had more in common even then with the bands that became your friends a bit later, people like Pink Floyd. But at that time, musically, you had more in common with Bert Jansch and John Renbourne. RH: Yeah, you’re right. PB: The next album that you are releasing in this group is 'Flat Baroque and Berserk', which was the first one to reach the charts and have real commercial success. RH: The first one had created some interest in me. It was in Jimi Hendrix’s collection of records that he was playing when he died. All these things that are known by people... they know the things he was playing when he died. Mine was in that pile. So it had made its mark - a sufficient mark to enable me to carry on. So then recording for CBS was next, but they wanted things from me that I was never going to do. So that little venture failed - not miserably, but it was just incongruous. The third one was exactly what I wanted to do, but... all these records were made very quickly. The first one was made in a single day. The second and third were made in just two or three days. tthat’s it. You didn’t have more than one take on anything. So when I came to do the fourth record, EMI were forming an underground label, as much as EMI could ever do anything like that, because at the time they were a giant corporation. But they wanted to somehow tap into what was happening in the clubs. There were a lot of things happening that would obviously be de rigueur in a couple of years and they wanted to get in there. They had lots of people – the Edgar Broughton Band, Pink Floyd, the Move and Deep Purple. I made a good record, I think. It’s a bit patchy, but overall it’s a good record. This was when I was writing a record a year. It was actually a commercial hit.... it made the top twenty. And they were very encouraged. For what they expected, that was a big success. It was a promising time. I’d got a new manager, Peter Jenner, who I got along like a house on fire with. Everything then moved up a couple of steps and I knew that I could achieve a certain degree of popularity over a long period of time. PB: 'Flat Baroque' has one of the first instances of you doing an explicitly political song in 'I Hate the White Man'. RH: Very political. I guess that I always felt as a young person that I was discriminated against, because I had in a step mother a Jehovah’s Witness who could not believe that I could not believe in that kind of a religion. So I had a feeling of what it was like to be discriminated against, and then I had the whole litany of human history to look at and people being killed in huge numbers for no real reason. And you had to relate that history to reality. It’s not really very pleasant, and totally against the ethic that we had built up at the time, in the late 60s. And so it was about the right moment for someone to write that kind of a song. We’d all seen in our youth, films about cowboys and indians. And the cowboys had always won. That was the wrong ending, the wrong story. Then there was the whole thing in South Africa, which was abhorrent. It didn’t border on ridiculous. It was awful, awful. It was foul. And I just thought the time was right for a song like that. And I did it... and there was a lot of people who said “yeah, great”, but there were people of course who hated it. That song and that album, they polarised a lot of people. But, from that album onwards, I tended to have a very dedicated audience. They became dedicated. They didn’t always become dedicated from the point where they came in and listened to their first record, but if they got the kind of messages that were on there... very human messages. Records were a bit like a blog then for young people. They were our way to get to the world - to post messages to the world. So I got a very dedicated following, although it was never really in mass market numbers. But we did sell, we sold well over 100,000 records. It was a minor hit. If you could sell that many albums now, you’d have a major hit. PB: From there you took some of the ideas you had been working on, and made 'Stormcock', which was an especially focused album – four very long songs. RH: I just thought, okay this has been a hit. I’ve now got the legitimacy to do what I want. Little did I know that I wasn’t going to carry the EMI executives with me. Far from it. Peter Jenner and myself started work on 'Stormcock', and we had three songs down quite quickly. I was on the night shift, I would spend the night in my car in the EMI car park, and through the morning everybody would come and knock on the window. Then I’d be up in the afternoon and we’d take the night shift over, as nobody else was going to work at night. Except the engineers that I’d purloined. They were really willing to do it. Not only because it was really great fun. I wasn’t going to be as austere as Cliff Richard or anything like that, but also I provided maybe three or four people at Abbey Road with their mortgage over the next five or six years, doing late nights. I became very friendly with them, and they’d look forward to the overtime. It was great. But the record, I’d made the first three tracks and I knew that it was going to be, as far as I was concerned, the best thing I’d ever done. I thought that this was a germ that, if I carried it through, was going to fuel me for the next few decades. I needed a last song. We found that the record wasn’t long enough. It was just three songs. It needed an intro. I found a song that I had thrown away, and revisited it as a social commentary. I compared the prisoner on death row to the artist in front of a critic, two different verses, and called it 'Hors d’Oeuvres'. It was the perfect opening. I thought it made a fantastic record, but rumour of it had gone as far as the executives, and they weren’t pleased. What they wanted was an absolute copy of 'Flat Baroque', something with songs like 'Another Day' on it. They were angry, really angry. And they dismissed it out of hand. I’ll never ever forget the meeting with the marketing guy, and we walked in, into the meeting and the first thing he said was, “Before I begin, I’d just like to say that there is no money left in the marketing budget for this album.” So we started off knowing that it was dead in the water. Pete and I tried to fight for it, because we knew that we’d made a really great thing. It was a long way ahead of its time. But they wouldn’t even release it in the USA because there were no singles on it. Initially it didn’t sell as well as 'Flat Baroque'. Slowly people caught up with it, and it became the biggest seller. But it became then a very difficult time. I’m particularly bloody minded when it comes to writing what I want. I think EMI were hoping I’d say, “Okay I’ll write you a record full of singles”. Then I could go back on the rack. But I wasn’t going to do that. I was going to press ahead with what I wanted to do. So EMI and I fought for a long time. It was a real struggle. Eventually in subsequent decades, 'Stormcock” did as it should have done. PB: So what made you want to write these long, epic songs? RH: Well, I’d been influenced as a twelve year old by Keats and Shelley, particularly be Keats, and later Shelley. For a younger person who is desperate to fall his first girlfriend, or whatever, Keats is brilliant. There’s something in it you recognise, and as a thirty year old you look back and think that those are young people’s poems. Keats died as a young man. He wrote young people’s poems. And they are really brilliant for any young person that wanted to get into English literature. I was enthused by it and inspired by it. One of first things I got into was 'Endymion', and it’s so long, and I really loved it. I really loved it. I’m still inspired by thinking about it now. So I wanted to write in that language, in that way, because it was already there. So in my head, there was no question about where that was coming from. It had germinated nearly twenty years before it actually came onto those records. I was very happy with it, I was incredibly happy with it. PB: It is the lyrics on that album that hold it together as a piece. Especially the song 'Me and My Woman', that is a collection of lots of different musical pieces held together by a single lyric. RH: That’s a great song, I think. PB: We then move on to the next album. I’m not sure quite how to say it... RH: 'Bullinamingvase'. Bull In A Ming Vase, ha ha. PB: I was expecting you to correct me! By that point your songwriting and recording style had changed quite a bit. RH: Yes, although there is still,'One of Those Days in England'- still the epic thing, still Roy Being Roy. But I really loved 'One of Those Days', the long version. PB: I like the short version, as well, actually. RH: Well, the short version was made. Peter Jenner said to me, “I’m telling you, if you write a few verses of 'One of Those Days in England', we will have a hit”. And I thought, “Ohhhhh.........” And Pete said, “Do you want a hit or don’t you?” So I said I’d have a go at it. I did it so quickly, in a few days. I already had the music. All I needed to do was write something mild mannered. And we so nearly had a hit. Here’s what a corporation does for you. Everything was going to plan, and Robin Nash was the controller of BBC 'Top of the Pops', and he said, “The moment it reaches 40, you’re on”. And it was doing so fantastically well, and it was at 42, and he was still saying, “The moment it reaches 40, you’re on”. And that week was the week they decided to give the single away free with the album. The mind boggles. It didn’t sell another single. I mean, talk about goobs. They made three, maybe four, really huge errors with my career. But, you know, I don’t really want to talk about it as a sad story, because it’s not any more. I don’t want to talk about being marginalised, because then I will be. And that’s not the point. The point is to get these albums to as big an audience as possible. A remote possibility exists. That’s what I’m trying to do now, expel all those negatives. They don’t do you any good. There’s no point moaning about it for forty years. You have to pick yourself up and smile. PB: There aren’t many people who could sell out the Royal Festival Hall, after all. RH: Yes, that’s actually true. And not in six days either! That was a feat. We thought that we’d put in on sale in June, give it plenty of time to sell. And looked on the internet the next day, as you do, and there was a quarter sold already. We were overjoyed. I thoughtm “What?” But then that gives you an incredible responsibility. You think that people bought the tickets because they really want to be there. You’d better produce. PB: You’ve played the Royal Festival Hall before. RH: Oh yes, I think this will be something like the seventh gig there. I did it in 1968. That was a great gig. I headlined with Tyrannosaurus Rex, and we were supported by Stefan Grossman, a great New York finger style player and by David Bowie, who was miming to a tape machine. PB: What do you like about playing there? RH: I used to think of the Albert Hall as the village hall of England. It had all that history. But in recent years, it has become less like that. You get a lot of season ticket holders - I don’t know whether they actually turn up. I think they buy the whole season, but just go to one or two things. And the Festival Hall has taken over, in a way, from the atmosphere that the Albert Hall used to have. It’s got the same British heritage. It’s owned by the country more than the Albert Hall. It’s owned by London, and it’s almost London’s hall, and I like that. I still like the Albert Hall, but it also has a big problem when it comes to putting on Roy Harper gigs - the ground floor seating isn’t raised at all, so if you’re at the back of that, you can’t see a damned thing. It’s not raised for a very good reason. It’s a listed building, and it’s a very important building, and you wouldn’t want to do anything to damage that. But... Once you get to the seats around the sides, then it’s a brilliant place to sit and watch gigs. But the people in the bottom bit, you can’t get to them. You can’t see them, they can’t see you, and that’s a bit off putting. You want to be able to know that you’re communicating with everyone. So the Festival Hall has taken over in my affections. PB: So you’ve got this concert coming up, and obviously there is the re-issue programme. But your website says that you have officially retired? RH: I am reeled out every now and again. I can be brought in. It depends on the size of the hook. What I have been doing over the last decade is consolidating the catalogue, the legacy. And it’s not very easy to do that. I’m transferring magnetic tape or often taking it straight from vinyl to CD. There are often artefacts all over it that you have to listen to in the studio and remove. You can’t always go back to the magnetic tape. You can now go into minimal levels of frequency loss. There is almost a longitudinal frequency to go with the horizontal frequencies... (he demonstrates his mixing board with his hands...) that doesn’t make much sense written down! But you can actually go into the track at lots of different levels, and find a particular artefact that wasn’t there on the original and take it out. The waveform will show you where it is. I’ve found myself in order to take some of those artefacts away in the transfer to digital going to minus 24 DB to actually get rid of them. You’re going down into it and taking out that little piece. But there is only so far you can do that without affecting the other instruments, so it’s hard. So that is what I’ve been doing in recent years, as well as taking care of the company, and that’s not easy. The hardest part about it is to come from talking to somebody about the possibility of releasing vinyl, and dealing with open ended questions with manufacturers and distributors. And then when you finish that in the daytime, you have to pick up the guitar in the evening and think, “Where was I?” It just doesn’t work. I struggle on, but I know that the time has come. I just have a really powerful feeling that if I don’t make this next record soon, it’ll just drift on and on. I’ve got quite a few songs now and I know that I’ve nearly got enough material to make an album. In another couple of months, I’ll have enough. It’ll be wonderful. It’ll be my 42nd record, if you include compilations. It’d be really wonderful to start work on a new record. I want to do that. I’m enthused, particularly at this moment. I’ve got all kinds of help from all over the place. I’ve got a whole generation of young Americans, people who have been influenced by my stuff. People like Joanna Newsom, Jim O’Rourke and Jonathan Wilson. I saw Jonathan Wilson a couple of nights ago, and I was amazed by how good he was. I had no idea. He’s making a compilation of my songs, sung by over people. He’s been working on it for a couple of years. He’s really serious. My publishers have spotted that this is happening, and they are going to get people like Kate Bush, Peter Gabriel, Robert Plant, my fans from among my peers, and try and get them involved. So that there is also a voice from over here. It can’t be just an American voice. I’m excited and inspired by projects like that, because it has come round again, a whole new generation inspired by what I do. Almost unbelievable. But I’m really enjoying it. So this new record, I really have to do it. PB: Thank you.

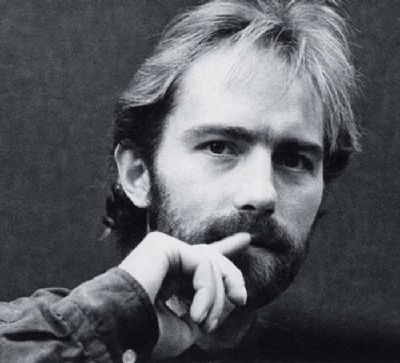

Picture Gallery:-

Visitor Comments:- |

| 465 Posted By: Anthony Browne, Blackpool on 22 Aug 2011 |

|

I read,here,that the talented Mr.Harper,whose songs and guitar i've always adored,more than most british singer-songwriters,is to actually ,many years since his last studio album,record a new batch of songs!!i am delighted to read this news...even at ,dare i say it,70 years of age(can hardly believe it) his brain ticks far better and creatively,than most human-beings!!!I hope you find the right studio,Roy,and are truly,truly inspired,as and when you do record a 'new' album!!!how about a long ,long song,in there somewhere?....his music is a timeless legend!!!

|

| 461 Posted By: Bob Jacobs, Newbury, UK on 18 Aug 2011 |

|

Thank you for really drawing some interesting chat out of Roy. I feel a renewed sense of optimism from Roy and hope that his music will finally get the recognition he deserves.

|

profiles |

|

Roy Harper (2011) |

|

| Malcolm Carter reflects on the career of English folk/rock singer-songwriter Roy Harper, who is celebrating his 70th birthday by making his entire 19 album catalogue available online for the first time and also releasing a double CD compilation, ‘Songs of Love and Loss Vols 1 and 2'. |

most viewed articles

current edition

Peter Doherty - Blackheath Halls, Blackheath and Palace Halls, Watford, 18/3/2025 and 21/3/2025Armory Show - Interview with Richard Jobson

Liz Mitchell - Interview

Deb Googe and Cara Tivey - Interview

Lauren Mayberry - Photoscapes

Max Bianco and the BlueHearts - Troubadour, London, 29/3/2025

Garfunkel and Garfunkel Jr. - Interview

Maarten Schiethart - Vinyl Stories

Clive Langer - Interview

Sukie Smith - Interview

previous editions

Heavenly - P.U.N.K. Girl EPBoomtown Rats - Ten Songs That Made Me Love....

Trudie Myerscough-Harris - Interview

Doris Brendel - Interview

Beautiful South - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

Pulp - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

Dwina Gibb - Interview

Kay Russell - Interview with Kay Russell

Barrie Barlow - Interview

Sound - Interview with Bi Marshall Part 1

most viewed reviews

current edition

Davey Woodward - Mumbo in the JumboNigel Stonier - Wolf Notes

Wings - Venus and Mars

Kate Daisy Grant and Nick Pynn - Songs For The Trees

Only Child - Holy Ghosts

Neil Campbell - The Turnaround

Philip Jeays - Victoria

Darkness - Dreams On Toast

Suzanne Vega - Flying With Angels

Charles Ellsworth - Cosmic Cannon Fodder

Pennyblackmusic Regular Contributors

Adrian Janes

Amanda J. Window

Andrew Twambley

Anthony Dhanendran

Benjamin Howarth

Cila Warncke

Daniel Cressey

Darren Aston

Dastardly

Dave Goodwin

Denzil Watson

Dominic B. Simpson

Eoghan Lyng

Fiona Hutchings

Harry Sherriff

Helen Tipping

Jamie Rowland

John Clarkson

Julie Cruickshank

Kimberly Bright

Lisa Torem

Maarten Schiethart