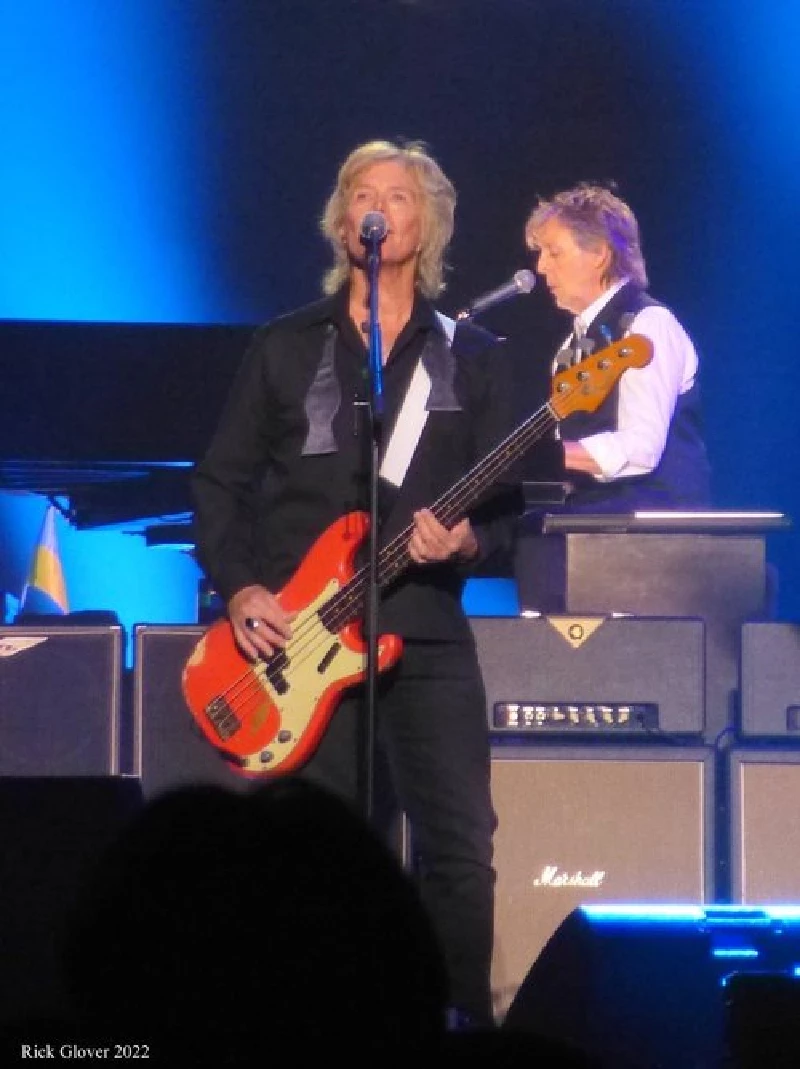

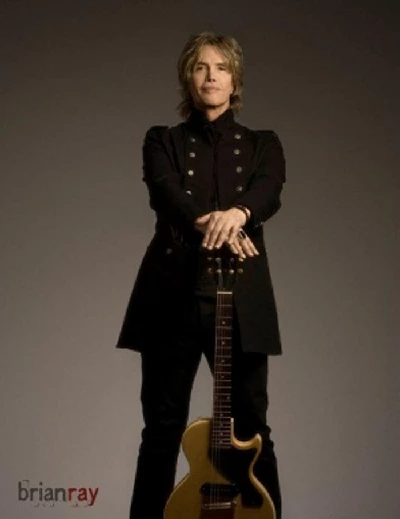

Californian guitarist-songwriter-producer Brian Ray lost no time racking up 10,000 hours in the music business, having started immediately after high school. Once unleashed, he hit the ground running. His CV includes decades working as a touring musician with Paul McCartney and a 14+ year career with vocalist Etta James as musical director/guitarist. Ray’s solo career sparkled too: in 2006, he released “Mondo Magneto” and in 2010 he achieved acclaim with “This Way Up”. Oliver Leiber (son of hit songwriter Jerry Leiber) and Ray formed The Bayonets in 2011, and after adding Argentinian singer Lucrecia Lopez Sanz the trio released a hard-hitting and stunningly original album called “Crash Boom Bang!” in 2014, re-releasing it three years later. Their talented guests have included keyboardist Adam MacDougall of The Black Crowes, bassist Davey Faragher (Elvis Costello) and bassist Schott Shriner (Weezer). The Bayonets have recently made ‘Argentina’ and B-side ‘Post Apocalypso’ available in a 7in single format and a stream via Wicked Cool Records. Lisa Torem initially caught up with Ray in October 2011 and was thrilled to catch up with him again to talk about conceptualizing video work, active listening, collaborating, producing and the exciting highlights of his career. PB: You’re credited as producer on these songs. Is that a longstanding role? BR: I love producing. I’ve been producing since basically I was a little kid, or thinking of myself as a producer. I self-produce all of my solo singles but when it comes to The Bayonets, it’s me plus Oliver producing and we do all of the writing. I only co-produce when it’s The Bayonets or a side project. I’m a producer. I love doing it. PB: As a producer, what makes you say “this is the final cut”? BR: It’s more than, is this the final take, right? Today, and it’s a good thing, all of us have in-home studios. You can record endlessly. You have so many options: a million-and-one snare drums, for instance, and if you want to replace the snares, you can. If you want to add a snare on top of it, you can, but there is a danger of overdoing it. So, it’s a fine line between experimentation and insanity where you just keep going and going and going. I have a great time producing and I often can hear the record in my head before I start the production which means all I really need to do is fill-in-the sounds. Paint by numbers. You just fill in the sounds and the roles that I hear in my mind. Does that make sense? I will spend about, let’s say, five days, six hours a day on recording a single and then another day or two with editing and finishing and fine-tuning it. PB: How does it work co-producing with Oliver? BR: It’s different all the time. Even with The Bayonets, more often than not, we will bring in the song that we worked on and then finish it together. In the case of about three songs in our collection, Oliver brought in songs and we finished together. It doesn’t matter where they come from. Similarly, I probably take the lead in terms of production ideas but it’s only because when I bring in a song, I can hear the song in my mind before we even start recording. And then, rather than explaining it, we just get about doing it. I should also add that Oliver is an amazingly gifted producer and writer on his own as well. He could easily be the lead producer on any of this stuff, as easily as it is me. Like in the song, ‘Sucker for Love’ from The Bayonets. That was a track that Oliver started pretty far down the road. We didn’t have a B-section, we didn’t have a chorus, but we had that whole intro and verse feel. PB: ‘Sucker For Love’ has a catchy title and fun hook. BR: I came up with the melody, but that was very much Oliver’s baby, as well as in another song, ‘I Feel Love’. It’s mix and match: whatever gets the job done. PB: On ‘Argentina’ you feature sax as a lead solo instrument BR: I just had this wicked idea that the song would just shortcut to a wall of saxophones playing a rhythmic and melodic arrangement around a melody and chordal movement. We just went about it. I found this guy Danny Lipsitz and asked him if he wanted to do it. Danny had offered to play with us before so I took him up on it. He said, “I can get a studio tomorrow night”. He brought five saxophones with him: a tenor, alto, baritone, and a few other things down to the studio and we did it over Facetime. We spent a couple of hours together and then, when we had the outline of it done, like, what was the content? Then, I asked him to fill it out because he was going to triple each part and make it really big and wide. PB: Were you notating parts or playing by ear? BR: No, this was by ear. I imagine that Danny probably does have it written, knowing him. He probably does have it somewhere, but as for now, it’s probably just on the record. PB: On ‘Whatcha Got’ the vocal contrast between you and Lucretia is pretty intense. Was that pre-arranged? BR: That was a wacky song idea that was very different. Oliver and I had come up with what I thought was a great idea, about who the lead guy was in that song: an old blues braggadocio, ragging about himself and all the cool stuff he has, all the cool stuff he can do, and why he’s such a bad-ass. Then, in the chorus, Lucretia would acknowledge that, and is pretty much saying, “I don’t care what you thought, show me what you got”. That’s the idea: enough talk, honey, let’s see what you really got. Less salesmanship, more, you know, be with me. I just thought, it was a really sexy and fun idea. Lucretia’s vocal, the way it’s delivered in sort of an intense, spitfire way. I heard an old dance record from Europe in the ‘90s sometime. I don’t remember the name, or who it was, but it was wacky, and the female singer had a really tough and bratty approach: a no-shit kind of approach, and it stuck in my mind. I remember how the voice falls off at the end of the line and at the beginning of the line, it goes up. Like the Beastie Boys. And I thought it was so catchy and cool and we just worked together. It was like acting. She killed it. She really delivered it so well. I’m so proud of that song, and how she did that. Oliver played his ass off on drums, and Scott (Shriner) from Weezer was on bass. Adam MacDougal from Chris Robinson Brotherhood is on keyboards and me on guitar. It was a fun session, that was very much live in the room and the vocals were done in the side studio later. PB: You’re old school, Brian. You enjoy being in the room, right? BR: I do. PB: Why? BR: It’s different things. I love being at home in my flip-flops and shorts, working on a track, and very relaxed, with the windows open and coffee maker upstairs. That’s great but there’s great value with being in the same room with men and women, sharing the same bowl and having a bunch of laughs, working together to carve a song. You know? And there’s a great advantage to that. You’re getting ideas in the pot and you’re all throwing things in. There’s no right or wrong idea. The idea is: “dare to suck”. That means any idea you have is cool. Don’t be so conscious of your idea. Just put it out there. We’ll share your ideas. Sometimes, you come up with better stuff as a result. PB: ‘Vagabond Soul’ brings to life the story of an outsider’s lost dreams. It’s deeper and darker thematically than other tracks. BR: The idea of The Bayonets as a project was, let’s create a band with its own name and its own musical identity. We sat down at one meeting and agreed about doing that project and then decided what that sound was, like, Duane Eddy guitar, with stripper-noir drums. That kind of talk-talk, sexy drums, along with dusty sounds and very live in the room. Big on ambience, and then, having a female singer aboard. So, we ticked off all of those boxes with The Bayonets’ music. You’ll hear a lot of those influences: low, single-note Duane Eddy. Dirty old guitar. Dusty old tom toms with an old drum set, and then, Lucretia and I singing. Oliver’s lyrics tend to go more into fun and sexy, whereas as a solo artist, I can sing about whatever I want. I did a little more working with Oliver into that sort of role-playing, as in, ‘Sucker For Love’ and ‘Whatcha Got’. Those are more role-playing, where you are becoming that character. That’s fun for me, but it differentiates between my solo material and The Bayonets material. I came up with ‘Vagabond Soul’ in a hotel in London. I sent a voice memo of the guitar and the first vocal to Oliver and he said, “We’ll work on it when you come back”. As it started developing, the lyric became more confessional than any other Bayonet song. We talked about it. Oliver said, “This is different for us,” and I said, “Yeah.” I thought, it was a good idea to have a revealing song in there; roll the veil back a little bit. It meant being humans with deeper emotions. We went for it. It was very much a story of a guy – me – who spent his life on the road and his life in the world, searching for deeper meaning, and carrying off where his dad left off. His dad couldn’t get out there and travel the world because his dad didn’t want him to. So, it’s very personal, a little bit of my story with my dad. He became very intrigued with my career because I was doing something that his dad didn’t want him to do. His dad wanted him to open a car dealership and sell cars for him, where I took a different path. My dad and I became very close and bonded over my new career. That’s what ‘Vagabond Soul’ is about. PB: You’re keeping a dream alive for generations. That’s a beautiful theme. BR: I think so. It’s beautiful. PB: When you conceptualize harmonies, can you block them out in the same way that you block out instrumental hooks? BR: When you decide that a certain part wants a harmony, as a person coming up with a melody, you automatically hear what that is, what they call a “close harmony”, a third traveling parallel to every note of the melody, or is it more “open sounding”, or what we would call in music, a fifth or a fourth or a sixth. So there’s a variety of approaches. You decide if the harmony is above or below the melody and then you decide how close or how open you want that to be. And then, you just connect stuff, and that is something that we would do together. Truly, as the person who comes up with the melody, I would block our backgrounds as well. PB: How long did it take you to learn to process these musical ideas in your head prior to working with other people in the studio? BR: That’s a good question. Some songs come together really quickly. Zero effort. Other ones? They come, to me, as a guitar riff. And it grooves into, what is this song? What is the title? And along with the riff, the tempo is built in. It’s different every time. There’s no one way or another to do this. But it can be as fast as a day or as long as weeks. Sometimes, it takes a while for an idea to germinate in your imagination until one day you go, “I got it”. It all comes together. You can hear the record and, as I said before, you just go ahead filling in the blanks. It’s an odd thing, man. It’s almost like, it’s weird to almost take credit for songwriting because in a way, and it sounds like a cliché, but it comes through you. You hear a lot of novelists, and all sorts of writers, saying that they are a channel and they just stay open for ideas to come through and it blasts through them. It captures them and then, they turn it into something. Then, you learn, don’t think, that you’re automatically going to remember a good idea. You’ve got to write it down, and that’s not something that you don’t automatically learn along the way. “Oh, man, I had this great idea! Where is it?” And then, it’s gone. PB: ‘Crash Boom Bang’ has a distinctive, masculine guitar riff. Inspired by? BR: I was thinking of those songs, like, ‘Everybody Needs Somebody To Love’ that great old song that The Stones did. There was a whole motif, a whole modality in those days, that single-note guitar thing that the bass would often follow like in ‘Dirty Water’. It started with that. I said, “Let’s do one of those classic ‘Everybody Needs Somebody To Love’ licks,” and then, we started working on an idea for the lyric, and I said to Oliver, “Would you be bummed out if we sang, “crash, boom, bang?” because that’s a lyric from ‘Jail House Rock,’ a lyric that his father, Jerry Leiber, had written. (With Mike Stoller, Leiber wrote ‘Hound Dog,’ ‘Kansas City,’ among other songs.) He felt weird about it, at first, and then he said, “No, I really like it.” So, that’s what we did. “She’s all ‘crash, boom, bang.’” We thought of it as a really strong, powerful female presence. We thought that would be so fun, you know? And as males that are into equality and empowerment, we thought that that would be a fun thing to do, and to go in that direction without being objectifying. It’s not a physical thing, necessarily, as it is an energetic thing. PB: ‘On My Way To You’ was voted “the number one coolest song of the year“ by Steven Van Zandt. This is the quintessential road trip love song. Great rhythm guitar and meaty guitar solos. The video is part live-action and part animated. How did the visuals come together? BR: We’re switching over to my solo stuff now. ‘On My Way To You’ was my most recent solo single, and as you said, it was voted “coolest song of the year” on Steven Van Zandt’s Underground Station. I was blown away. I couldn’t believe it when I got that phone call that morning from Michael Des Barres. He said, “Congratulations on your song.” I didn’t know what he meant, you know? I woke up and there was more news from other people. Then, it started to be clear that my song has won “coolest song of the year”. All these great artists had songs at the Top Ten. I was really chuffed. That started out with the introductory guitar riff and then, the kick drum coming in and really insistent. It’s a theme that I’ve used for all of my songs for a long time, which is, I’m gonna pick you up and we’re gonna skate out of this place, whether it’s this town or this planet. As the lyrics got direr, it was more about, let’s get out of this planet. So, while it used to be, “let’s get out of this town,” in a song that’s so “Easy Rider” from The Bayonets, now, we’re going to get into my ’65 Rivera that’s going to turn into a spacecraft and we’re out of here. It’s a little more extreme in terms of escapism. We did that at home and went over to my friend Eric’s house and got drums from him. Bassist Davey Faragher Elvis Costello came to my house in Santa Monica and we did bass. I did all of the keyboards, guitar and percussion. Vocals was Scott Shriner with Davey Faragher and myself on background vocals, and I sang on the chorus. The solo was done with an old Marshall amp with an old Gibson guitar. It’s hard to screw up when you have those things coming. The video was out here. I have a getaway house out in Palm Springs and we set up a green screen right here in my carport. So, all of those scenes where it looks like I’m in an abandoned car garage: that’s all green screen in my carport in Palm Springs. Then we actually drove my ’65 Riviera around the streets of Palm Springs. You’ll see a dusty, drone shot of the car in the intro. from up above and that’s all around here in Palm Springs. We drove around, did it all in a day and picked it up the next morning. Tim Roth, who did the video, knows the guy who did the CGI animation. Then we turned the ’65 Riviera into a spacecraft, with the fire coming out of the exhaust pipe. It was fun. PB: Did you have lengthy discussions about how the band would visually depict specific songs? BR: Some more than others. ‘Whatcha Got’ was a pure performance video with little else going on. It was over at Oliver’s studio in the big room with Scott Shriner, on bass, Oliver, on drums, Lucrecia and myself. We would shoot some singles of each of us, as well. And my good buddy, Brian French, cut it together. ‘Sucker For Love’ was very conceptual. I think, Brian came up with that treatment. He got his wife, Linda French, to bring over some dancers as contestants and we built a little set in Oliver’s garage with the bamboo wall and a silly sign. It was really just a fun video to do. ‘On My Way To You,’ the latest one, was very much a concept I had of turning the car into a spacecraft. I asked Jim (Wilson, videographer) if he could do that. He came up with the green screen and CGI environments, whether on an open road on a bridge or here in my garage. PB: In a video with Etta James from 1975 at Live at Montreux, we see you playing guitar against Etta’s monster-of-a vocal on ‘I’d Rather Go Blind’. A YouTube fan commented: “Etta isn’t singing the song. She’s reliving the moment.” What was going through your mind, considering that Etta was so much in the moment, but you were on the hook to accompany her? BR: I’m spoiled rotten by playing with Etta James for fifteen years and then, knowing her and being close to her for fifteen years after that, and then, to play with so many other greats, and then to play with Paul McCartney. Between Paul McCartney and Etta James, these are two of the most important people in musical art, ever, in my estimation. We watched as Etta James has really grown into a legacy that I always knew she deserved, even though, the world hadn’t caught on, in the same way that they had caught on to Aretha Franklin. Etta really has to get her due. Everyone knows that Etta James is the bomb. Back to your question, she was very much a performer who was dedicated to being in the moment. Some nights, she would do, what we called “the bridge”: an eight-bar section in the middle of the song. Maybe she would do that twice one night, but on the next night, she wouldn’t do it at all. My job was to watch her and guess where she’s going next or catch where she’s going and translate that to the band. In the case of the Montreux Festival, I was just about to turn twenty. She was thirty-six. I was there as a real greenhorn. I was a kid and out-of-my depth with these incredible players. I seized the moment and kind of rose to the occasion to the degree that I did. You can see me there on the edge of my seat, you know, learning to translate those signals to the band. That was my job. Sometimes, Etta would raise her arm to get everyone’s attention, but she had a very direct connection to me. It was my job to relate that information. So, you’ll see me sometimes—I’ll be looking at her, and across the stage at the same time, you’ll see me signalling to the band, because she was in the moment. We had to follow it. This was so much fun and really, really great stuff. PB: This circles back to the art of active, creative listening. BR: While the arrangements may not change from night to night as much, Paul is a different kind of performer, and these are songs that we all know, whereas Etta is more in the moment, reliving these moments, as that YouTuber said. But within each song, Paul can change little bits and bobs all the time and you have to be on your toes. He can change how he sings or plays something, so all of that training that I talked about with Etta really came in useful with Paul. You have to be ready. Etta might skip over a whole section on purpose or not. Who cares why? But you’d better be there. It’s very simple. Your job is to do what she’s doing. PB: That’s quite the lesson for up-and-coming musicians. BR: It really is huge. As a kid coming up it’s very important to develop those talents, playing with other human beings in a room. It requires listening and it’s the same as acting. Actors will say that great acting is more about listening than talking. It’s about being aware of your other actors and responding. Not dictating every moment but responding to what’s going on around you in an honest and human way. It’s the same thing with music. With music you have many things to think about: time, consistency, so it doesn’t speed up or slow down. You have to think about taste and dynamics. You can’t just play at one level like you rehearsed in your room and go play with people. Now, you’ve got to play that thing you learned in your room and play it sensitively: up and down in intensity, and then, it becomes music and its very important stuff. PB: I read that you have always worked in the music industry. Have you ever dreamed about working in a Subway Sandwich shop or something similar? BR: Not so much a Subway, but maybe a Carl’s Jr. because I love that Beyond Burger, no, when I was a little kid, like any young male kid, I thought about being a fireman or a race car driver, but honestly, rock and roll caught my attention and I was in hook, line and sinker by the time I was four. I was a goner. I knew what I wanted to do and it was going to be that. PB: For a biopic of your life, what would be the best time and setting in which to roll the film? BR: In Glendale, California, where I was raised as a little kid, in the middle-class area, with my dad going to the car dealership, and my sister, fifteen-years my elder, Jean Ray, taking me over to her girlfriend’s house and playing Elvis Presley, Little Richard, The Everly Brothers and Rick Nelson on the little stereo and then squealing away over pictures of these rockers, and me looking up at them with my mouth open, “Okay, this is obviously the thing to do.” That’s the place where I would start. PB: I’m going to do a little “five for five” here. Ready? PB: Favorite color? BR: Blue. PB: Mine, too. Favorite non-musical activity? BR: Classic cars. PB: Nice. Favorite superhero? BR: That would have to be Iron Man. PB: Favourite song that you did not write or co-write? BR: That’s a tough one. Maybe ‘Like a Rolling Stone’. PB: Favorite fiction or non-fiction book? BR: I really like, believe it or not, 'Casino'. I thought that was a really exciting book. PB: What’s coming up in the near future for Brian Ray? BR: I’m just really enjoying having a place to have my collaborative music played: that is Little Steven’s Underground Garage on satellite radio at Sirius XM 21. It’s just such an honour to be driving down the road and you hear a song and go, “Oh, that sounds cool. Wait, that’s my song”. That never, ever gets old. And Little Steven and Janet Mortensen and all of those guys and gals at Wicked Cool Records give me a reason to get up in the morning, a reason to be joyous every day, playing music and to have a place to release my music. it’s just such an honour. And I’m not 21 anymore and it’s not something that I would ever take for granted. I’m very happy about that. I’ve got more Brian Ray solo stuff coming up. I have three songs in the can and a fourth one germinating. And it’s very possible that we’ll do a collection of my singles and add to it three or four new unreleased tracks as part of a vinyl release. We’ll see. With The Bayonets I got us a singles deal with Wicked Cool Records. So once in a while when the mood strikes, we’ll sneak into the studio, record another song and release it. PB: Thank you. Photographs by MJ Kim

Band Links:-

https://www.brianray.com/https://www.facebook.com/brianrayguitar

https://twitter.com/brianrayguitar

Play in YouTube:-

Picture Gallery:-

intro

In a second interview, Lisa Torem catches up with guitarist/songwriter/producer Brian Ray, acclaimed for his solo work, as well as with Paul McCartney, Etta James, and The Bayonets, who have recently released dynamic new singles.

interviews |

|

Interview (2011) |

|

| Brian Ray is both Paul McCartney's current guitarist and was also for fourteen years Etta James's musical director. He speaks to Lisa Torem about playing with McCartney and James, and also his long solo career and recent album, 'This Way Up' |

most viewed articles

current edition

Carl Ewens - David Bowie 1964 to 1982 On Track: Every Album, Every SongArmory Show - Interview with Richard Jobson

John McKay - Interview

Colin Blunstone - Thalia Hall, Chicago, 16/7/2025

Bathers - Photoscapes 1

Billie Eilish - O2 Arena, London, 10/7/2025

Loft - Interview

Visor Fest - Valencia, Spain, 26/9/2025...27/9/2025

Sir Tim Rice - Interview

Robert Forster - Interview

previous editions

Manic Street Preachers - (Gig of a Lifetime) Millennium Stadium, Cardiff, December 1999Heavenly - P.U.N.K. Girl EP

Beautiful South - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

Peter Perrett - In Dreams Begin Responsibilities Interview Part One

Boomtown Rats - Ten Songs That Made Me Love....

Oasis - Oasis, Earl's Court, London, 1995

Coldplay - Wembley Arena. London, 16/8/2022

Trudie Myerscough-Harris - Interview

Prolapse - Interview

Pixies - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

most viewed reviews

current edition

Davey Woodward - Mumbo in the JumboSick Man of Europe - The Sick Man of Europe

Lucy Spraggan - Other Sides of the Moon

Amy Macdonald - Is This What You've Been Waiting For?

Phew, Erika Kobayashi,, Dieter Moebius - Radium Girls

Suzanne Vega - Flying With Angels

Bush - I Beat Loneliness

Alice Cooper - The Revenge of Alice Cooper

Blueboy - 2

Cynthia Erivo - I Forgive You

Pennyblackmusic Regular Contributors

Adrian Janes

Amanda J. Window

Andrew Twambley

Anthony Dhanendran

Benjamin Howarth

Cila Warncke

Daniel Cressey

Darren Aston

Dastardly

Dave Goodwin

Denzil Watson

Dominic B. Simpson

Eoghan Lyng

Fiona Hutchings

Harry Sherriff

Helen Tipping

Jamie Rowland

John Clarkson

Julie Cruickshank

Kimberly Bright

Lisa Torem

Maarten Schiethart