Tony Visconti - Interview

by Lisa Torem

published: 11 / 3 / 2019

intro

Seminal producer Tony Visconti talks about working with drummer Woody Woodmansey with Holy Holy, recording with David Bowie in the studio and his legacy.

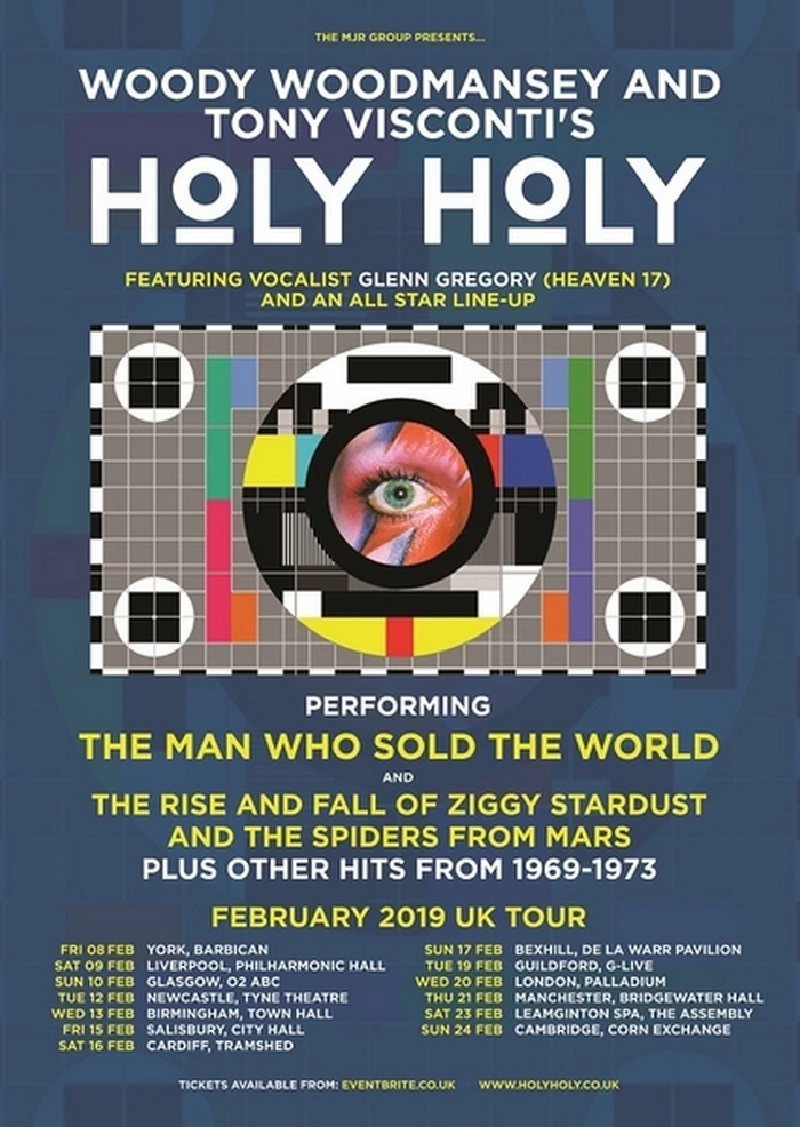

From February 8-24, 2019, Holy Holy will grace prominent UK halls, theatres and pavilions. The David Bowie-inspired ensemble features producer Tony Visconti, who played bass on 'The Man Who Sold the World', and who worked alongside Bowie on landmark albums including Bowie’s final record, released in 2016, the award-winning Blackstar. Holy Holy also features original David Bowie drummer, Woody Woodmansey, powerful vocals, courtesy of Glenn Gregory (Heaven 17) and other surprise artists. During this much-anticipated run, Holy Holy will perform in their entirety 'The Man Who Sold the World' and 'The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars'. In addition, they will concentrate on deep cuts recorded from 1969-1975, which blissfully benefited from Visconti and Woodmansey’s creative minds and souls. Despite a demanding tour schedule and a constant flurry of daily events, the in-demand Tony Visconti still found time to conduct his first interview with Pennyblackmusic. Read on to discover more about the Holy Holy tour, Tony’s reactions to working in the studio with David Bowie and more in this exclusive interview. PB: Your highly original bass part on the recorded arrangement of 'The Man Who Sold the World' is an essential component of the listening experience. How many tracks did it take to come up with the finished song? How did you come up with this compelling bass line? TV: I had classical and jazz training which coincided with growing up wanting to be a rocker like Elvis, Chuck Berry, Buddy Holly. In composition class my teacher pointed out that the classical composers not only wrote great melodies on top, they also wrote great melodies on the bottom to be played at the same time. My brain went there when I first heard David’s simple sparse melody. In the time he sang, “Who knows, not me,” that’s four notes, I played sixteen notes on the bass and continued to on the next section of the chorus. These are just scales I would practice daily, but put to good use in this song. Mick Ronson jumped right in. Mick encouraged me to play more melodic bass a la Jack Bruce. PB: The February Holy Holy Tour will undoubtedly attract fans that are very knowledgeable about the Bowie canon. Will it also generate interest from newcomers? TV: I think David Bowie gets more newcomers to his music than any other artiste who has passed away. Where there is no age limit at our venues we see children as young as eight singing the songs we play. I’ve seen three generations of families in our audiences, from the tykes to Granny and Granddad. Seeing this makes me quite emotional. When David and I were making this music in the 70s we knew we were onto something good, but couldn’t imagine the impact he would have decades later. PB: Your relationship with drummer Woody Woodmansey harkens back to The Spiders from Mars era. In a previous interview with Woody, he recollects that when he first approached you about the Holy Holy idea, he wasn’t sure you’d be up for the project, but was delighted that you were. How did you both envision the project back then and how have you modified the act? What makes this upcoming tour unique? TV: Woody and I go back much earlier than the Spiders from Mars. We were briefly called Hype (David’s name for us) during the making of 'TMWSTW'. At that point, Woody was the best drummer I had ever played with — so open-minded and extremely talented. I hadn’t played live very often in recent years leading up to the first Holy Holy show, and that’s because I opted to be a studio rat instead of a live playing musician. I was reluctant to take on such a gruelling prospect as touring. I never toured in a proper bus, sleeping in bunks, etc. The tipping point was when Woody called me personally and told me we should play ‘TMWSTW’ live in its entirety because we never once did that back in the day! He was right. As soon as we finished the album David’s then manager Tony De Fries told David he didn’t need a band. We were sacked. Mick and Woody went back to Hull with their tails between their legs. It took David a year to realise what great musicians they were and asked them back to play on what was to be ‘Hunky Dory’. I had other work to do, I was busy producing records for Marc Bolan and T. Rex and several other British artistes so I went back to the stage with Woody and the rest of our band, Holy Holy, to play a great prog rock album we all had a hand in creating, ‘TMWSTW’. PB: You have worked as producer on a considerable number of David Bowie albums, ending with the award-winning 'Blackstar'. How did you first meet David, and at what point did you work out a production agreement? How would you describe your process of working with David in the studio over the years? Can you cite an example of when you both agreed, ‘This is the right track’ and when you disagreed? TV: I met David in 1967 when he had already dabbled in the pop world but just couldn’t write for the mainstream. He had passed through several bands and managers and one of his London friends was Marc Bolan, who was in the same situation — talented, different and unsignable. My boss encouraged us to work together as I was already making some headway with Marc. David was a different story. I loved his voice and writing but rock was not his end goal. He loved musical theatre, acting, mime; he was a young Renaissance Man. We experimented lots in the early days. I was not only working on music with him, I helped him with his live mime shows when he was studying with Lindsay Kemp. We began to make some headway with the ‘Space Oddity’ album. The one consistent thing in his style was that he wrote on his 12-string acoustic guitar and that was the centre of all the songs on that first album. It was a very loose album; he was front and centre with a rock band, Junior’s Eyes, playing behind him. We were definitely going to make a second album after we decided we needed to go heavier, get a killer guitarist and drummer and make a specific band for the next album. It unfolded that Mick Ronson came into our lives and he brought Woody Woodmansey with him. We were a great band, in my not so humble opinion, but we went too far in the other direction with very complicated songs and arrangements. Getting the balance was difficult. We all wanted to make hit records but it took David and I going in different directions to learn how. A couple of years passed before he invented Ziggy Stardust and I had my first big hits with T. Rex. After we came back together we had learned a thing or two. I wasn’t always David’s producer but I did groups of albums with him in several decades. The 'Young Americans’ — ‘Diamond Dogs’ period; the ‘Low’, ‘Heroes’, ‘Lodger’, ‘Scary Monsters’ period; the ‘Heathen’ - ‘Reality’ period; and finally ‘The Next Day’ and ‘Blackstar’ period. We were so familiar with each other’s work; we were like brothers in the studio. There was never an argument about anything. Whomever spoke first with an idea, the next sentence would embellish that idea, whether it was David’s or mine, it was quickly ours. We always met before an album started, just the two of us to map out the plan, decide on musicians and what to go for as regards to style and sonics. The ever-evolving dialogue would continue in the studio, with the musicians present. Hardly any idea was rejected, every idea was considered then either used or discarded. PB: ‘All The Madmen’ is just one example of your musical flexibility. There are both baroque and heavy metal aspects to this arrangement. Bowie wrote the song as an empathetic tribute to his mentally ill brother, Terry. Was it a challenge to bring this idea to fruition? TV: ‘All The Madmen’ is a very evocative song. David explained what it was about and it was our job to musically convey that message. It was one of the harder songs to record. We had a little cellar where we rehearsed, where we all lived together in Beckenham. ‘All The Madmen’ was one of the more rehearsed songs. I got Woody to play a jazz bolero beat in the instrumental which was good to jar up the message a bit. We worked hard on that one. Mick’s guitar playing is sublime! At this point I’d like to confirm that we all wrote our own parts and we’d help each other refine them. We all had our say about the arrangements too. PB: In 1974-1975, you produced ‘Young Americans’ at Philadelphia’s Sigma Sound studio and in New York’s Record Plant and Electric Lady studios. Personnel included guitarist Carlos Alomar, vocalist/arranger Luther Vandross, drummer Andy Newmark, saxophonist David Sanborn and vocalists Robin Clark and Ava Cherry. The new lineup and “plastic soul” genre represented a cultural shift in David Bowie’s career. What do you recall about the recording of the vocalists? What was your perception of the Sigma Kids? TV: ‘Young Americans’ was a most enjoyable record to make. We had all new musicians, with the exception of Mike Garson on piano. The rest of the musicians were crazy good and that included Andy Newmark on drums, Willy Weeks on bass (my idol) and Dave Sanborn on alto sax. Carlos Alomar was a fresh-faced kid from the Bronx and brought a style of guitar playing that was definitely one of the strong building blocks of that album. But Luther, he was a big blessing. He was a friend of Carlos and Robin Clark; they were schooldays’ friends. Luther was the choirmaster. When it came time to do backing vocals Luther would sing everyone’s part until they learned them confidently. It was all done off the cuff, spontaneously. There is a tape floating around of Luther, Robin, Ava and Carlos learning their parts for ‘Can You Hear Me’. It is extremely enlightening. David and I can be heard talking from the control room cheering them on and suggesting ideas. Nothing really took long to record, everyone was so talented and professional. The Sigma Kids started out to be annoying fans but then it kicked in that they were beautiful kids, great fans, great people to chat with. We got to know each other very well and I know many of them now! Of course we had to invite them into the studio to hear the album when it was nearly finished. They knew all the songs anyway because they listened at the back door of the studio the whole time we were there and the soundproofing was terrible. PB: David’s final album, ‘Blackstar’, received multiple awards. According to a Rolling Stone magazine article, although David was terminally ill during this time, he assumed he would have more time to work and expressed a desire to do another project with you. TV: David was very upbeat during the making of ‘Blackstar’. I had a Face Time conversation with David two weeks before he passed and he was in a very good mood. He said he had five new songs in the works and he wanted to start a new project as soon as possible. I have never heard those songs although I was certain I would. I have no idea at what stage they were in, full songs, melody only, just chord changes? I don’t know any more about them. PB: In general, when you make a decision to produce a project, what are your expectations of your client and are they generally met? TV: This varies. I have learned to proceed at the client's pace. Some artistes are fast, some are slow, some are positive, some are negative. It takes me a little time to see what I’ve really got to work with; when I find it, I try to bring out the best parts of an artiste. And I always push them to give 100%. There are very few albums I’ve produced that I regret making. Oh, mixes could always be better a year later, ask any record producer. PB: Damon Albarn (Blur, Gorillaz) described your role as producer as being “part psychiatrist, part confidante and part music conductor.” Does that description ring true? TV: Yes. I love Damon. He’s part Mahler, Thelonius Monk and Russian mystic. PB: You scored the orchestral arrangements for Paul McCartney and Wings’ ‘Band on the Run’. How did this work? Did you show up with the completed work or did you and Paul discuss the process along the way? TV: I had already known Paul through working with Badfinger and my wife Mary Hopkin. I got a phone call from Paul asking me if I actually wrote the T. Rex string parts and could I read and write music? The answer was yes and I met up with him on a Sunday afternoon at his house in St John’s Wood. Mary and our young son Morgan came with me. We were all in a big living room with the McCartney kids making a fuss of Morgan. Paul and I sat at the piano and worked out the orchestral arrangements for ‘Band On the Run’. He had a little Tandy cassette recorder to record his ideas which he hummed as he played piano, or the rough mixes from another cassette machine. He never played the entire songs but just the part where he wanted me to write parts. The fear of being bootlegged was very strong in those days. I was asked to write and record these arrangements by Wednesday morning. Needless to say, I lost a lot of sleep in the process. Paul gave me top lines and trusted me to fill in the rest of the notes an orchestra would play. He gave me a lot of freedom. We also collaborated on a song on the ‘Venus and Mars’ album. I also produced a track for Linda McCartney. PB: You have worn many hats since the onset of your career, but started your career as a guitarist. That said, on your Thin Lizzy projects, there’s a deep reverence for the twin guitar solo which, for many fans, illustrates their signature sound. When working intensely with an act via a series of records, as you did here, as well as with so many other popular acts, what’s your process for moving past the technical aspect of a recording and establishing a commercial brand? TV: It’s simple. Great music is full of ‘hooks’; melodies that grab your attention and remain in your head, commonly called earworms these days. Without hooks you can’t have a commercially viable recording. You will be viewed as avant garde. I wouldn’t say I’m a Top Ten hitmaker anymore because I gravitate towards working with artistes that have greater depth than Top Ten drudgery. But then I’ve always championed the underdog and I have had Top Ten hits with them. Bowie is certainly one of them. PB: As you prepare for the next Holy Holy tour, what is uppermost in your mind? What are your plans for 2019? TV: I have a few projects in the works, some big surprises for 2019. Right now, I’m booked for the next four months. As for the Holy Holy tours, I am practicing bass every day. My memory is amazingly good as Bowie songs are very tricky, even the simple ones like ‘Jean Genie’ keep me on my toes. PB: If you could relive one day in your life, which one would you choose? TV: I don’t look back, except to reference my older work whilst creating new stuff. Honestly, I get out of bed every day, do all the morning things, which includes Tai Chi practice, then I get back to work. I love making music. I haven’t had a proper vacation in years. PB: Thank you.

Band Links:-

http://www.holyholy.co.uk/https://www.facebook.com/holyholymusic/

https://twitter.com/holyholymusic

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tony_Visconti

https://twitter.com/tonuspomus

https://www.facebook.com/tony.visconti1

Picture Gallery:-

most viewed articles

current edition

Spear Of Destiny - InterviewRobert Forster - Interview

Fiona Hutchings - Interview

When Rivers Meet - Waterfront, Norwich, 29/5/2025

Carl Ewens - David Bowie 1964 to 1982 On Track: Every Album, Every Song

Brian Wilson - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

Chris Wade - Interview

Pistol Daisys - Waterfront, Norwich, 29/5/2025

Credits - ARC, Liverpool, 17/5.2025

Nils Petter Molvaer - El Molino, Barcelona, 24/4/2025

previous editions

Heavenly - P.U.N.K. Girl EPBarrie Barlow - Interview

Boomtown Rats - Ten Songs That Made Me Love....

Dwina Gibb - Interview

Oasis - Oasis, Earl's Court, London, 1995

Sound - Interview with Bi Marshall Part 1

Manic Street Preachers - (Gig of a Lifetime) Millennium Stadium, Cardiff, December 1999

Beautiful South - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

Trudie Myerscough-Harris - Interview

Serge Gainsbourg - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

most viewed reviews

current edition

Peter Doolan - I Am a Tree Rooted to the Spot and a Snake Moves Around Me,in a CircleGarbage - Let All That We Imagine Be The Light

Vinny Peculiar - Things Too Long Left Unsaid

Little Simz - Lotus

John McKay - Sixes and #Sevens

Suzanne Vega - Flying With Angels

HAIM - I Quit

Morcheeba - Escape The Chaos

Vultures - Liz Kershaw Session 16.06.88

Billy Nomates - Metalhorse

Pennyblackmusic Regular Contributors

Adrian Janes

Amanda J. Window

Andrew Twambley

Anthony Dhanendran

Benjamin Howarth

Cila Warncke

Daniel Cressey

Darren Aston

Dastardly

Dave Goodwin

Denzil Watson

Dominic B. Simpson

Eoghan Lyng

Fiona Hutchings

Harry Sherriff

Helen Tipping

Jamie Rowland

John Clarkson

Julie Cruickshank

Kimberly Bright

Lisa Torem

Maarten Schiethart