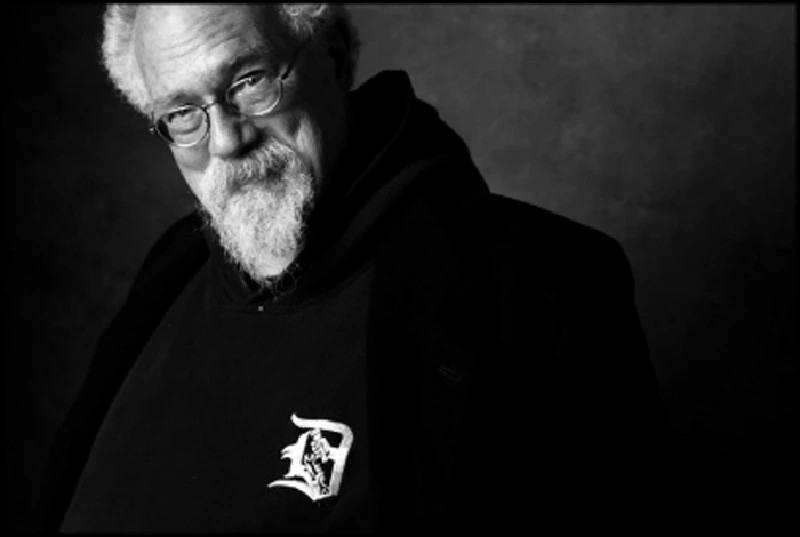

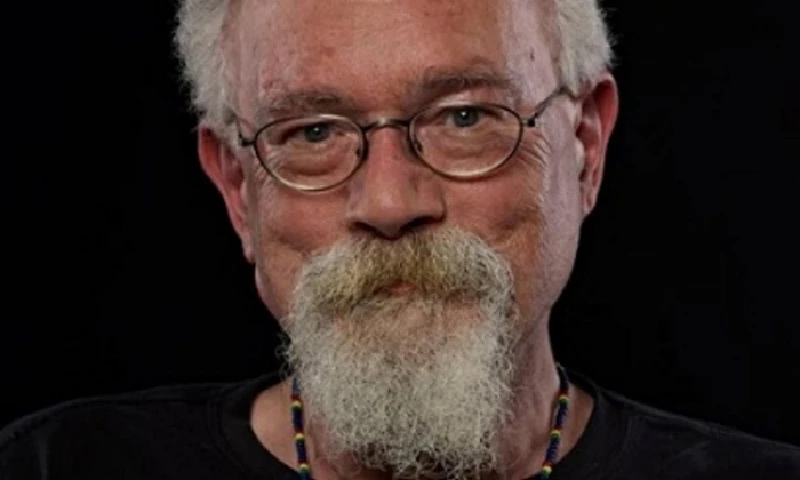

John Sinclair - Interview

by John Clarkson

published: 3 / 5 / 2014

intro

Poet, writer and former 60's far left counterculture leader John Sinclair speaks to John Clarkson about his ever controversial views on drug culture, his new blues album 'Mohawk' and managing influential Detroit-based 60's band, the MC5

The 420 Café, which is one of Amsterdam’s coffee shops, is situated in Oudebrugsteeg, a narrow and small alleyway with tall, overhanging buildings on either side. At one end of Oudebrugsteeg is Nieuwendijk, a bustling shopping street of mainly chain stores, and at the other end Damrak, the main thoroughfare between Centraal Station and Dam Square and a tacky strip of Starbucks, Kentucky Fried Chickens, over-priced souvenir shops and endless roadworks. Amidst the uniformity and the franticness of everything that is going on beside it, the 420 Café stands out both in its individuality and its serenity. Its owner’s cat can be frequently seen scampering around inside. While most of the remainder of Amsterdam’s dwindling number of coffee shops specialise in banging techno music, Frank Zappa - posters of whom adorns the 420’s walls - and other classic rock acts of the 1960s are the mainstays of its music system. Less than a walk of five minutes from Centraal Station, and with several allegedly especially potent varieties of product for sale, “the Cannabis Café”, as it was until two years ago called, has proved particularly popular with American visitors. The 420 is a regular haunt for poet, writer, 60’s far left counterculture leader and ex-convict, John Sinclair. Sinclair, who is now 72 and who self-describes himself on his website as a “pioneer of marijuana activism”, first visited Amsterdam in 1998. He relocated there permanently in 2003, and now spends approximately six months of the year living in Amsterdam. Amsterdam is a long way from Sinclair’s early roots in Flint, Michigan as a small town rock and roll/jazz enthusiast and teenage disc jockey. In the early 1960s Sinclair moved to the Michigan state capital, and in 1964 co-founded there the Detroit Artists Workshop, a radical arts collective, theatre and printers. Two years later Sinclair met the rock group MC5 after they played a gig there, and soon afterwards became their manager. Now seen as enormously influential, the MC5 fused jazz, blues, psychedelia and garage rock, and were early influences on both the heavy metal and punk/new wave genres. They also served as a mouthpiece for the left wing politics of Sinclair, who in 1968 formed the revolutionary White Panthers, whose ten point manifesto included the abolition of capitalism and a “total assault on the culture by any means necessary, including rock and roll, dope, and fucking in the streets.” In February 1969, the MC5 released their debut album. ‘Kick Out the Jams’, a live record, on Elektra Records. The album was successful, selling over 100, 000 copies in its initial weeks of release. Later that year, John Sinclair - who had been found in possession of cannabis twice before and already had served a short prison sentence of six months – was, however, found guilty of selling two joints to an undercover policewoman and sentenced to nine and a half to ten years in jail. The MC5 were dropped by Elektra Records because of their inflammatory nature, and signed to Atlantic Records. While Sinclair was in prison, the MC5, abandoning their previous political convictions, dropped him as their manager. The group recorded two more albums, ‘Back in the USA’ (1970) and ‘High Time’ (1972), but both of these saw dwindling sales and found the band playing to diminishing audiences. Most of the members of the MC5 by now were also battling drug problems, and the group broke up in late 1972. John Sinclair spent two and a half years in prison, and was released in December 1971 three days after the John Sinclair Freedom Rally, a huge protest gig which was attended by 15,000 people and whose headliners included John Lennon and Yoko Ono, took place in Ann Arbor in Michigan. Sinclair continued to lead the White Panther Party, which had been renamed the Rainbow Coalition Party, until the mid-197Os, finally disbanding it after the resignation of both Richard Nixon and his Vice President Spiro Agnew and the end of the Vietnam War. In recent years, he has focused on his poetry, and since 1996 has recorded over twenty albums of it, several with his band the Blues Scholars, which has had a rotating line-up including at one point ex- MC5 guitarist Wayne Kramer, and which sets his delivery to music. His latest album ‘Mohawk’ is a departure for Sinclair, being recorded with his Amsterdam flatmate Steve Fly who has added drums, turntables, cello-bass, flute and glockenspiel to Sinclair’s vocal lines. The poems are drawn from an epic set of verse which Sinclair has been working on for over thirty years, and each poem of which is inspired by a different one of the 150 songs that the jazz musician and pianist Thelonious Monk wrote during his lifetime. Many of the ten tracks on ‘Mohawk’ tell of the young Monk’s experiences playing in jazz clubs with Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker, while on ‘My Melancholy Baby’ Sinclair pays tribute to a friend who lost most of his possessions in Hurricane Katrina. John Sinclair has over the years divided people, winning as many detractors as admirers for, as well as his promotion of cannabis, his work with the MC5 and the White Panthers, who were described by the FBI in 1970 as being “potentially the largest and most dangerous of revolutionary organisations in the US.” Pennyblackmusic spoke to John Sinclair on the phone with hopefully an open mind. He was in New Orleans staying with his daughter, before moving on to Detroit to visit his other daughter and granddaughter. We found him only slightly mellowed with age, but erudite, witty and big-hearted, and began by talking with him about Amsterdam. PB: You spend about half of the year now living in Amsterdam. What is the appeal to you of Amsterdam? Is it simply its liberalism or are there are other factors as well? JS: It is so civilised. The authorities aren’t all in your business. Nobody’s armed. They don’t care if you get high. They’re not all beat up about sex. It is gorgeous physically to look at and to walk around in, and they have got brilliant public transportation. It is just so well organised. I like it. PB: The Netherlands is not quite the liberal country that it was. There have been increasingly strict rules in the recent years about coffee shops, and recent laws have been put through in some parts of it in which one has to be a resident of the Netherlands for a month before being allowed to smoke cannabis. JS: They didn’t really succeed in that, at least not in the cities. They succeeded with the little towns in the borders. There were 20,000 Belgians and Germans coming into these little towns of 3,000 every weekend, and it was driving the people that lived in these small towns nuts, so they pushed a law through. Then the government tried to extend that law everywhere, and the cities like Amsterdam and Rotterdam said, “No. Are you nuts? It is 25% of our tourist income.” They are, however, constantly trying to shrink the degree of liberalism as far as acceptance is concerned, even in Amsterdam. They started in 1995 requiring them to register and get licences, and then they tried to regulate it so that if a coffee shop closes for financial or other reasons then that licence won’t be renewed. They are constantly as a result reducing the number of them. They have gone from 750 to less than 250 in the City of Amsterdam in the last fifteen years. On the other hand, however, your experience of going to a coffee shop is the same. That hasn’t altered at all. There are less of them, but if you find one that you like and you go there it is great (Laughs). PB: You spend a lot of time in the 420 Café? JS: Yes, it is my headquarters. I am the poet-in-residence there (Laughs). I have been going there since 2001. The owner and I became friends, and he is also an activist. He persuaded me that I should place myself there, so I am very much at home at the 420. PB: The State of Colorado has recently made cannabis legal. You have just been on a fact-finding mission there. JS: I had a gig there, the Fifth Annual Neal Cassady Birthday Party, but I had the opportunity to buy some weed across the counter for the first time in the US after fifty years of waiting. It was an exciting experience. It was just like Amsterdam. They had a menu with different kinds of marijuana. We had to pay a tax there of about 20%. A $45 purchase has a $9.50 tax on it. It was pretty severe, but on the other hand they just took in three million dollars in their first month of selling - $2 million from recreation and almost a million from medicinal. PB: What is your take on harder drugs such as heroin and cocaine? JS: I think they should be legal. I don’t see what business the police have for what happens inside your head. What business is it of theirs? I don’t compute. If you do something wrong, then they should maybe correct you for doing something wrong, but what is wrong with getting high? Everyone gets high, one way or another. PB: It could be argued that heroin and cocaine are infinitely more dangerous than soft drugs. JS: Well, nothing is more dangerous than black market drugs. You don’t know what you are getting. You don’t know what might be a good or a bad purchasing situation. To go back to Amsterdam again, they seem to have better mechanisms for dealing with drug addicts. They used to have heroin addicts on the street when I first went there. Now they don’t. They remove them to a different place and they service them. They give them medical help. I don’t know what the full position is. They might give these addicts drugs, but that is not the problem. The problem is that they are illegal. If they weren’t illegal, you wouldn’t have drug cartels. They are - I think - a function of building a police state through the illegality of drugs. PB: Are you are suggesting then is that if drugs like heroin and cocaine were made legal they would be a lot safer? JS: I think that they would be if the consumer was able to go to a store to buy them. If you have to go to some ugly area full of criminals, who know that you are coming with money in your pocket, who will sell you anything if they can get away with it, then it is inevitably going to be more dangerous. PB: You were the manager of the MC5 in the mid-1960s. How did you first meet them, and what was the initial early appeal to you of them? JS: They moved into my neighbourhood. I lived in a bohemian neighbourhood near Michigan State University. These kids had been brought up in a suburb called Lincoln Park. Their lead singer Rob Tyner was a person like I was who wanted to be a beat (Laughs), so he moved into the bohemian neighbourhood and then the rest of them followed. We had a space called the Detroit Artists Workshop with a store front, so we invited them to rehearse there. That was pretty much how we hooked up. Rob Tyner and I became the best of friends due to our many shared interests, which started with jazz. PB: What do you think your main achievement was with them? JS: Well, I helped them organise what they were trying to do and made it happen in a sense. I didn’t know anything about artist management. I was a beatnik poet, but on the other hand I organised the Artist Workshop and I paid the rent and I kept the lights on (Laughs), and I knew how to make a car payment and things like that (Laughs). They were a little band from the neighbourhood. It wasn’t like I was signing up to manage the Beatles. They were guys that just needed to have a ride to the gig, and to make sure that they had guitar strings. They started out by playing the sort of places that didn’t have a backline. They were guys who were really into being loud and having a sound, and so they required amplifiers that worked and a sound system. I would organise all that stuff. Then I figured out how to get people to listen to their music. We made a little 45 in Detroit. We made 500 copies, and then we used it to get an album contract with Elektra Records. I then became involved in the music business hustling, getting the right people to listen to it and like it. PB: The MC5 were once “described as the guys who chopped down trees to clear the dirt roads and pave the streets, so that the rest of us can drive by in Cadillacs.” Would you agree with that statement? JS: I wouldn’t argue with that. The sad part to me was that they never got the Cadillacs. They had a musical approach that was pretty varied. They took a lot from the blues of John Lee Hooker and also tried to play like John Coltrane, and they had an influence. You can’t have heavy metal without the MC5. That was their concept – heavy metal. They were, however, on the ground floor with jazz rock and fusion as well and also blues rock. They were a great blues band – Fred Smith and Wayne Kramer (MC5 guitarists - Ed) were great blues guitarists. They mixed all that up with the Who and the Rolling Stones and a bunch of straight ahead 60’s rock, and they came up with something pretty special. That was what I was fascinated by. PB: Does it disappoint you that forty years on they weren’t more successful at the time? JS: There is nothing that can be done about it now. At the point they were taking off they decided that the direction that they were taking with me was the incorrect direction. They decided to be a regular band, and they wrote off a big part of their audience that liked them for what they were. They didn’t, however, succeed in getting a new one, so they never had the success really they could have. Their career went downhill instead of uphill, and as a result they don’t really exist in current life the way people do that had the hits. When they have a Top 100 weekend, you won’t hear the MC5 in there. Their sales were never enough. I feel bad about that, but then again in my art I don’t get an audience. I have just learnt to live with it. PB: It could be argued though that they powered the way for the future, couldn’t it? JS: Yeah, I think so. They did a lot of ground work. They won’t let them in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, and they should do. Patti Smith is in there, but not Fred Smith who was one of the greatest rock and roll guitarists of all time. PB: You were sent to jail for giving two joints to an undercover policewoman. That seemed even then whatever your take on cannabis a complete overreaction on behalf of the authorities. JS: I always say the opposite. I think it was a reasonable reaction. They sent me to prison for two joints, and I say that I insisted that they did that. I made a lot of trouble for them, and they reasonably responded in the best way that they could. PB: How much of that do you think was down not to drugs but because of your involvement with the White Panthers Movement? JS: Well, it was both those things. My case stretched back three years before I was convicted. It went back to December ’66, when I committed the crime of giving the two joints away, and then I tried to get the law judged unconstitutional before going to trial. We wanted to create an elaborate legal process, and then eventually after two and a half years they said, “No, you are going to have to have a conviction in order to challenge the constitution and the law,” and that is when I went to trial and got the conviction. The shocking part was that they wouldn’t give me an appeal bond. That was when the politics came in. They said that I was a threat to society, and they wouldn’t let me out on an appeal bond even though I wasn’t involved in any violence and it was a tiny crime. That was when they put me in prison, when they wouldn’t let me out on a bond. I had never anticipated that. PB: You spent two and a half years in jail. How did you spend your time in prison? JS: Well, I tried to use it usefully. I read, I studied, I wrote, I directed the activities of my organisation on the outside through meetings, and every single night I wrote home seven single space typewritten pages. I was also intimately involved with my own efforts to get out, as well as our political efforts and our newspaper. I just didn’t sit there feeling sorry for myself. I was trying to get myself out, and also we were trying to overthrow the government (Laughs). PB: Do you see similarities in your case and that of Pussy Riot in Russia? JS: Yeah, I love them. I think they are the best thing since the MC5. I said that to a friend of mine in Holland the other day, and he said, “Oh man! Their music is so awful.” I hadn’t even thought about their music. I haven’t really listened to pop music for a long time. It holds no interest for me, but I just like their politics. They are dedicated. I like them a lot. PB: You were freed three days after the Free John Sinclair Rally in Ann Arbor, which featured John Lennon and Yoko Ono. On your new album ‘Mohawk’ there is at the end of it a recording of a phone call between yourself and John Lennon and Yoko Ono just after your release. JS: I am not really responsible for that. I should have put on a disclaimer. The guys who put out the record put that on. I am not sure why. I have always tried never to capitalise on this in any way that could benefit me personally since I got out of prison. PB: Did it come as a surprise to you when you were made a free man? You sound absolutely shocked on the recording. JS: Yeah. I had no idea. I was surprised. We had been working within the law to amend legislature, and had actually succeeded the day before the rally in getting the legislature changed to reclassify marijuana and change the drug laws completely. It was one of those situations in which everything coincided in a really good way. PB: The White Panthers had a ten point statement which included a “total assault on the culture by any means necessary “, “demanding the end of money” and “freeing all prisoners and soldiers.” How many of these policies would you hold by today? Would you hold by them all? JS: Yeah, I am pretty good for them. Everything free for everybody. Yeah, sure. It seems like a good idea instead of everything being free for the 1%. In ‘The New York Times’ there was a story recently about the 1% having gone from owning 10% to 20% of American wealth in the last twenty years, and they were saying that this is not likely to downturn. Unless something is done they are going to keep gathering up more and more (Laughs). PB: What about freeing all prisoners? JS: That was a kind of simplistic way of saying how fucked up the prison system was. Some people need to be isolated from the rest of society, but not for getting high or for stealing a candy bar or cars. That is a hell of a thing for putting somebody in prison for. They should have hurt somebody pretty bad or killed somebody or manipulated the stock market. None of those guys on the stock market are in prison (Laughs). PB: What about “total assault on the culture by any means necessary?” Is that again within reason? JS: I am not sure that it would solve anything now (Laughs). It seemed, however, very important then. PB: Did your new album ‘Mohawk’ take a long time to record? JS: I am just the artist in this record. My producer is my roommate and drummer Steve Fly, who is actually from Stourbridge originally but who lives in Amsterdam. He attends the hash bar at the 420, and I live with him when I am in Amsterdam. This is a collaboration of ours, and really I just read the poems. I had finished this sequence of twenty poems and I wanted to record it, so he took me into the studio. We got a really good voice recording all in one day, and then I left for America the next day, He then went back into the studio and picked the ten he liked best, and worked with the engineer there to add the music parts to it. The reason I say this is that it is uncharacteristic for me. Usually I am involved in the production. I do my recitations with the music live in the studio or on stage. I am involved with the music in a physical way, so this was very different for me. I just did the poems, but I am really delighted with the way it came out. PB: A lot of these poems were written a long time ago. Some of them stretch back as far as the early 1980s. JS: They are part of a serial work in verse that I started in 1982, and that I am about two thirds of the way through now (Laughs). I am writing a poem for every song that Monk ever recorded. That is my project - to write a poem for all a hundred and fifty of them and I have written about a hundred of them so far in thirty years (Laughs). I have got two poems I have to work on, and then I will be done with the first half. My intention is eventually to take all the poems between 40 and 64, and then record them with Steve. They are numbered in sequence in which Monk recorded them. Number 36 would be the 36th number that he recorded, but when I write them I write them according to the inspiration that comes, and it might be 112. It might be 79. When we recorded these, I had just finished the last ones in that sequence. I can’t remember which ones, but I had all twenty of them. I would have liked Steve to have set music all twenty of them, but there was enough there for him to work on. PB: You are in New Orleans at the moment, and then will spend some time in Detroit. Will you return to Amsterdam after that? JS: I am coming back to London first of all because the record label is having a party for the record on May 11th. I may do some poetry readings in Britain after that, and then after that I hope to be back in Amsterdam by the end of May. PB: What are your plans after that? Are you going to do another album? JS: I am always going to write another album. I am always going to do another poem (Laughs). That is what I do. PB: Thank you.

Picture Gallery:-

Visitor Comments:- |

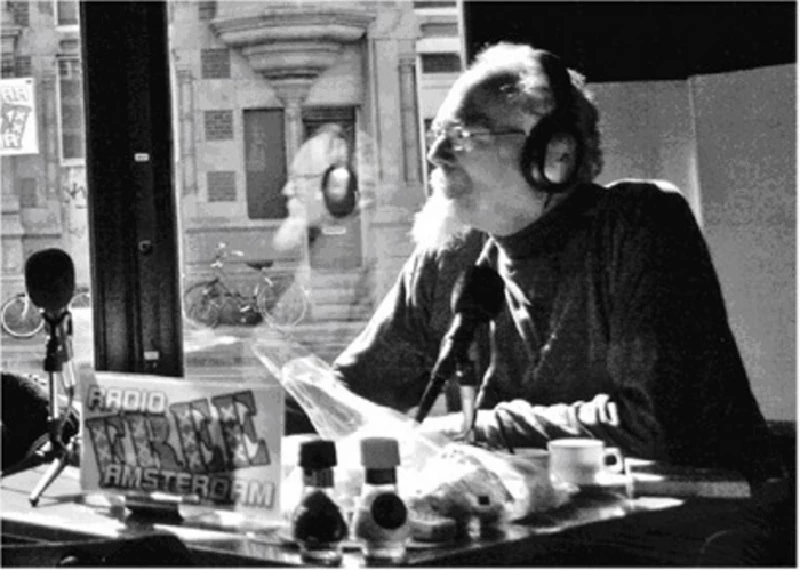

| 697 Posted By: David Gardiner, UK on 15 May 2014 |

|

I had the good fortune to bump into Mr Sinclair at the 420 coffeeshop with a friend, back in 2010. I had no idea who he was! :) We chatted a little, he was recording some speech into his laptop, but was just a regular guy with no 'airs' about him.

Upon returning to the UK, I came across a photo & article about him, and holy sh1t! I thought, I just met a proper hero!! :)

Since then I've regularly followed his Radio Amsterdam posts via Facebook, and can't wait to get a copy of Mohawk.

|

| 695 Posted By: Patricia Hinson, Grand Blanc, Michigan USA on 15 May 2014 |

|

He inspired my daughter Alex and I to open our eyes to the world around us. We are proud of him and proud to call him our Loving friend. Alex is now a Senior at the University of Michigan, Photo Journalist/Marketing, Thank you John. We Love and miss you already. Patty Hinson, Grand Blanc Michigan USA ♡

|

most viewed articles

current edition

Carl Ewens - David Bowie 1964 to 1982 On Track: Every Album, Every SongArmory Show - Interview with Richard Jobson

John McKay - Interview

Colin Blunstone - Thalia Hall, Chicago, 16/7/2025

Billie Eilish - O2 Arena, London, 10/7/2025

Bathers - Photoscapes 1

Visor Fest - Valencia, Spain, 26/9/2025...27/9/2025

Loft - Interview

Sir Tim Rice - Interview

Robert Forster - Interview

previous editions

Manic Street Preachers - (Gig of a Lifetime) Millennium Stadium, Cardiff, December 1999Heavenly - P.U.N.K. Girl EP

Beautiful South - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

Oasis - Oasis, Earl's Court, London, 1995

Peter Perrett - In Dreams Begin Responsibilities Interview Part One

Prolapse - Interview

Coldplay - Wembley Arena. London, 16/8/2022

Boomtown Rats - Ten Songs That Made Me Love....

Trudie Myerscough-Harris - Interview

Pixies - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

most viewed reviews

current edition

Davey Woodward - Mumbo in the JumboSick Man of Europe - The Sick Man of Europe

Lucy Spraggan - Other Sides of the Moon

Phew, Erika Kobayashi,, Dieter Moebius - Radium Girls

Amy Macdonald - Is This What You've Been Waiting For?

Bush - I Beat Loneliness

Suzanne Vega - Flying With Angels

Alice Cooper - The Revenge of Alice Cooper

Blueboy - 2

Cynthia Erivo - I Forgive You

Pennyblackmusic Regular Contributors

Adrian Janes

Amanda J. Window

Andrew Twambley

Anthony Dhanendran

Benjamin Howarth

Cila Warncke

Daniel Cressey

Darren Aston

Dastardly

Dave Goodwin

Denzil Watson

Dominic B. Simpson

Eoghan Lyng

Fiona Hutchings

Harry Sherriff

Helen Tipping

Jamie Rowland

John Clarkson

Julie Cruickshank

Kimberly Bright

Lisa Torem

Maarten Schiethart