Patrick Duff - Interview Part 2

by Denzil Watson

published: 15 / 1 / 2012

intro

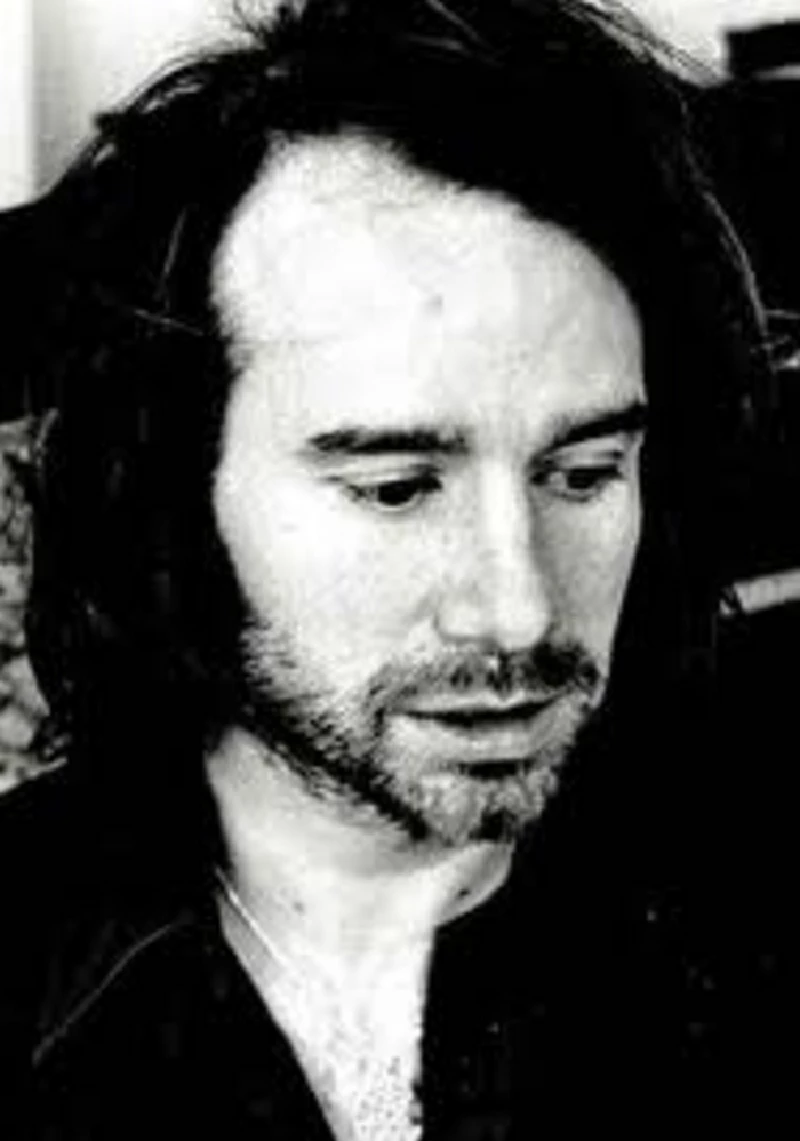

In the second part of his interview with Strangelove's Patrick Duff, Denzil Watson speaks to him about the hard times he suffered after the break-up of his short-lived band Moon, and his now successful solo career

Part one of this marathon interview took us through Patrick’s “band years”. No less honest or fascinating, the second part takes us from immediately after the break-up of Moon and troubled times for the Bristol-based singer-song writer right up to the current time with Patrick established as a well-respected solo artist. PB: What happened after Moon ended? PD: After Moon split up I basically went into this forest outside Bristol for about two years. PBM: Were you actually living in the forest or did you live at home? PD: A bit of both really. After everything that had happened to me, not just in the band but on a personal level as well, it was a really difficult time for me and I found it very hard to be around people. Being around people was a physical experience at that point. It was overwhelming so I needed to be on my own. So around then I started to have a relationship with nature and that was really important to me. I learnt a lot for doing that. I learnt a lot about the way it really is. Walking around in that forest I just learnt stuff at a deep level. Some of the time I was still thinking “I don’t know what’s going to happen to me,” but most of the time I was just looking at stuff. I’d never taken time to actually look at the things in the world that were around me. I looked at things when I was on acid and thought, “That’s fucking great, man!” Like “Wow, look at that view, man.” Or “Wow, look at that tree, man.” But I’d have forgotten about it by the time I was in the pub coming down of it. So I’d never looked at the world that I live in: the way that it is, the way that it grows and the way that it dies. I just listened to records and watched films. And that’s a different reality that’s been created by humans. Something within me was really up for that and I really needed that. I went through a transformation. It was like going into a cocoon. I still wrote songs, a lot of songs, but they were really simple. But they were just about fucking trees and shit, and actually to be quite honest I didn’t feel like playing them to anyone. I didn’t feel like having them slagged off for being “hippie shit” or whatever when they were really real to me. I wouldn’t have thought that consciously. I just didn’t play them to anybody. I wrote them for myself and about what was going on. PB: Did they ever get recorded? PD: No. I wrote a lot of songs during that period and they all went the same way as the songs from the Moon period. That’s another thing. If it had been now I would have recorded them and there would have been an album of them. But it wasn’t like that then. And I can’t even remember them. There was one called ‘Julie of the Rose’ which I still play. So that kind of made it thorough. It’s a very special song in that way, as it survived and still kind of resonates with me now. I tried to record it for ‘The Mad Straight Road’ but it didn’t come out properly. PB: So that period didn’t really influence your debut solo album “Luxury Problem” album that followed that period then? PD: No, that didn’t. That was a little capsule on its own. And then I met this guy called Thomas Brooman. I had this mate at the time called Merv, but he’s dead now. He kind of took me under his wing a bit. And he could see that I couldn’t live in the world. He knew me from when I was in Strangelove. He knew what I’d been through to a certain extent, and he saw me walking around Bristol on my own and basically he had compassion, this guy, even though he was a real rough-edge, you know. But he spotted me and he approached me, and he asked me to do a gig in a really small pub and I just said “Yes”. And I basically played these songs I was talking about in this pub. This pub belonged to Thomas Brooman who’d set up WOMAD with Peter Gabriel. And he came up to me afterwards, and he said he loved my songs and thought they were really amazing. And I looked at him .and I saw that he really meant it and that he’d been really moved by what I’d done. So I became friends with him, and then the next thing I knew was that he’d sent me a letter saying that he wanted me to become part of a song-writing collective or panel in WOMAD. This [gig] was the first thing I’d done since Moon had split up. The pub was really small, and it was the first public engagement I’d done in a few years after this experience in the forest. So I went and did this thing with Midge Ure from Ultravox, and he was on the panel with another Irish singer-songwriter, and we just spoke in front of an audience and then just answered questions on songs and I played a few things in a small room in the Rivermead Centre in Reading, and that is when I thought I might as well go and check the festival out. Up until then I’d had no interest in World Music whatsoever. Well, not no interest as I’d heard some Indian music that I quite liked. And I went round and checked out some of the acts, and that is when I saw Madosini who then was 81 years of age. I think maybe walking around this forest for so long I changed. And she’s been a sheppardess on the side of a hill playing her one-stringed instrument until the age of seventy nine when she got discovered. At the age of seventy nine! She didn’t know who Elvis was. She didn’t know who the Beatles were. She didn’t know that Brian Jones had died in a swimming pool. She didn’t know any of that stuff that I’d been brought up on. But when she played it was total rock’n’roll. It was raw and it was really from her heart. It was like the force of nature coming through her. And it just blew me away. It was like the nail in the coffin of all the “What’s going to happen to me” type of questions that had been going through my head. And “How am I ever going to get back on top.” Those ghosts were sometimes still haunting me and she just showed me that there was something else going on, beyond the kind of model that I’d been sold about what it is to be a musician. She embodies it in her presence. She’d lived this very different sort of life. When I saw her, I just started crying. PB: It sounds like a really life changing moment. PD: Yeah, it was really sort of embarrassing. I had to just crawl under this tarpaulin in the end, by the side of a tent because I was crying so much. It was embarrassing so I had to hide. I kept on crying for about half an hour under this bit of fucking tent. Something happened. Not out of nowhere as there was a lot of stuff that had led up to it. And Thomas being the sort of person he is, when I told him that I’d been really blown away by her, he said that the woman who looks after her while she’s over here is here so let’s go over and talk to her. So by the end of the day I was going to South Africa. I went there and I wrote songs with her with this translator, another thing that didn’t get released. But it changed me and then that’s a long story but at the end of it, by the time I’d finished working with her, I’d realised that I loved her music but I realised that I was a fucking rock’n’roller. That’s what I got from working with her, and I kind of went back to where I really came from which is an incredible story, but probably too long to start going on about now. It was amazing. And out of that the songs for ‘Luxury Problem’ came. PB: Something that did get released after ‘Luxury Problems’ was ‘The Mad Straight Road’ and I have to say when I heard that it blew me away. I was gob-smacked when I heard it. I didn’t really expect that. I suppose ‘The Lion and the Hawthorne Tree’ pointed the way. With the previous album, you could still hear the influence of Strangelove. PD: Yeah, definitely. That was something I needed to get out of my system with ‘Luxury Problem’ so I could move on definitely. I didn’t hear that in it when made it but that’s the good thing about making albums. You make them and you want them to be perfect, but they never are and then you’ve got a chance to work out where you are. PB: You came pretty close with ‘The Mad Straight Road’ though. PD: Well, thank you. PB: You put an enormous amount into your second solo album, didn’t you? You could see that from the roll-call of musicians involved with it. Was it disappointing that you had to self-release it in the end? PD: Yeah, it was to a certain extent, but it was wicked for me to make a self-release. It was a massive step for me. When I made that album I sent it out and there was a guy called Paul Connolly who was really interested in it and at the time was managing me and trained the Spice Girls earlier .and he was a really nice guy. He used to be head of Virgin and he was really into my music and his approach came out of the blue and he said “I want to help you,” and I went round loads of record companies with him and sat in offices and played for these bosses who were his personal friends. And I played ‘Spider Woman” and this was all before it was recorded and I was basically trying to get signed. He was trying to get me signed. At that time I wouldn’t have tried to gone out and do that but he was showing interest so I went in that direction. I sent that album to him and all these people when it was finished, and my girlfriend at the time had basically supported me by lending me the money to make it. None of them got back to me about it. PB: I have to say I’m astounded. PD: None of them got back and I felt sad at the time, but I knew I’d given all that I could give. It wasn’t easy making that album. It was very enjoyable, but it was really hard towards the fucking end to get it finished. I ran out of money,and you’re trying to get people to do things on favours and it’s hard. But I got it made and it felt like, “Bloody hell, I’ve really given myself for that. And I want some reward”. But it didn’t come in a financial way. So in the end I just thought, “Fuck it, I’m going to release it on my own and I’m going to play the concerts on my own. I don’t have to ask any one for a favour. I don’t have to do any worrying. I’m going to fucking do it myself.” PB: If you compare the situation to when you were in Strangelove with the label doing everything for you, you’d really gone full circle, hadn’t you? PD: (Laughs) Yeah, I have. And I can honestly say that from “The Mad Straight Road” I’ve had the best ever feeling from any album I’ve done because it survived longer than any other album I’ve done. I have to say that I’ve never listened to it since I did it. You put so much into it you can’t really listen to it afterwards. There are so many memories. It takes so many years for you to have any sort of acreer. I hear the odd track now and again if it’s on shuffle on my iPod. It’ll come on and I let it go and listen to it. PB: One of the things I like about the album is its universal appeal. On one hand my two-year-old son likes dancing around to ‘Three Little Monkeys’ and my 80 plus Auntie Joy likes ‘Dead Man Singing’. It has such a wide range of appeal. PD: Yes, it does. And I’m really happy with that album. I did the best I could and I was really excited and loved it when it was finished. And I still am and I carry it around with me when I do my gigs and sell it to people. It still feels like it is still alive. With the Strangelove albums as soon as they’d gone out of the charts, it felt like they were over. It’s because that’s how they were treated. They were treated in that way by everyone around us. You just got the feeling that “that albums over now.” ‘The Mad Straight Road’ is still alive because it’s not in that world. PB: The things that you sing about don’t just end, do they? PD: Exactly. So that’s been great to find out. And that I am looking forward, and that I do have a place in music in my own way and I am going out and doing gigs. I’ve had to really practice guitar to get good enough to do these solo gigs. PB: There’s no hiding really is there because there’s you, your voice and your guitar and your songs? PD: And it’s good. There’s no having to worry “Is everyone alright with the guy who’s playing guitar or whatever. Are they alright, are they OK with me?” In a band there is a lot energy that goes into the relationships between the people. I really hope one day I will collaborate with people, but it won’t be me going asking anybody. It will be people coming to me and wanting to do it. I’m not going to go out asking people to do any favours for me. PB: It’s quite ironic that you do one-off gigs in London and Bristol and around the county, but you did a lengthy full-blown tour in Holland and Germany, isn’t it? PD: That’s because of the promoters. I ran a song-writing workshop after about 2003 after I’d met Madosini as I wanted to pass on what I’d learnt from her about music and the opportunity came my way. Somebody said, “Do you want to run that song-writing workshop for her and we’ll pay you £50 for each time you do it once a week?” I was skint so I said, “Yes”, but I’d also had this experience with Madosini so I ran that workshop for quite a few years and it was really successful. It was a really good time for me. I’d become really conscious about what I’d learnt. I was having to explain it to people. You have to engage your left brain to try and put it into language which I don’t really do so that was really good for me. The was a girl on that course called Katie Brooks, and she was picked up by this promoter in Germany and she went on to tour, and so she said to me, “Why don’t you go and do that?” so she gave me the guy’s number. It was like a chance meeting like everything is for me. So I’ve done three tours this year and it’s been great. PB: And next on the horizon is ‘Seven Sermons to the Dead’ that dates back to 2006 right? Sounds interesting, can you tell us more about it? PD: That’s another kind of side story. What happened was this bloke called Vic Ecclestone who works for Bristol City Council. He was a great guy, a cool guy. He was a maverick in a way. He used to spend Bristol City Council’s money by putting string quartets on buses and stuff like that. And people would say, “Why?” and he’d say, “There’s no reason for it”. He was like that. He was a real intellectual who did odd things. He commissioned me in about 2006 and he said, “I want you to write something that will go with the choir in Bristol Cathedral”. So I thought okay, here’s my chance to write a Christmas song. I like ‘White Christmas’ by George Michael. There are Christmas songs I really fucking like and I wondered if I could write one of them. So that’s what I set out to do but I just wasn’t that happy with it. So that was hanging about in the air. And about the same time as that this other guy came into my life through Thomas and he was called Steven Leschak. His father was Michael Jackson and the Rolling Stones and Frank Sinatra’s lawyer. His dad was a Jewish guy from New York who was musical royalty. So this guy Steven had been around this all his life. He’d managed Ozzy Osborne when he bit the head off a bat, and had to try and go down and get him out of jail. He was a total crook in a way, but I really liked him. He was my manager and he was Elliot Smith’s manager whom I really liked, so it was wicked. This guy started managing me and he introduced me to these two guys from Salt Lake City. He was in Glastonbury and he said “You gotta come down to Glastonbury, man,” so I went down to meet him there and he introduced me to these two blokes who were friends of his, and they produced and manufactured these things called “Singing bowls”. They originally came from Tibet and they are metal, and you hit them on the side with a mallet and stroke them and they give out this drone. So these guys had made these bowls but they’d made them out of Quartz crystal instead of metal and they were in Britain. They were doing a tour with these bowls and they were going round retail outlets trying to find shops to sell them in the UK. So we met for dinner and got on quite well and went back to this doctor’s house in Glastonbury, and they got out these bowls and started playing them all together. It was like the inside of a Zen monastery. They said they would give me a lift back to Bristol as they were on their way to the airport to fly back to the US that evening. So they gave me a lift back to Bristol and dropped me off. It was late and I got out at my house, and they started driving up the road and I was waving them goodbye, and then the car went into reverse and came back up the road towards me, and this arm came out of the window with this big case of seven of these bowls, and they said, “We’ve got a feeling that you’ve got to have the bowls”. And they gave me these bowls that were worth thousands of pounds. I never knew it at the time. They just gave them to me on a whim or their intuition, and then just drove off like I’d never met them. So then I stared to work with these drones. And then I thought this is what I’m going to use to do this piece for the choir. I’m not going to use guitar. I’m going to do it with these. So basically I wrote this piece called ‘Seven Sermons for the Dead’, and it’s an hour and a half long and it’s very challenging in a way. It’s like a series of readings, singing, quiet bits, chanting and visionary poetry. It ended up being an hour and a half long and too much of an undertaking. The guy who commissioned it loved it but the guy who was supposed to be helping me with the choir couldn’t fucking get his head round it at all basically. So it never got performed. But I phoned up the guys who had given me the bowls and I said, “Look, I’ve written this piece. Can I come out and play it to you?” So they flew me out to Utah and I played it to them live, sitting on the floor of this studio and they just said, “You’re just going to record that now. Here’s a recording studio, and you can go in tomorrow so tear up your plane ticket because you’re going to be staying here”. So I did it myself. I just over-dubbed my own voice for the choir parts. At one point I overdubbed 28 voices on one bit. It was hard work. PB: It’s a good job that it’s going to finally come out given all that hard work you put into it. PD: Exactly. But I did it in 2006 and it’s taken this long because Steven and these guys fell out at that point about some business deal. Steven doesn’t talk to them and they don’t talk to him as far as I understand. So my album got lost in that hole. But this year they got back in touch with me and said that they’d put it out. So I’m just doing some extra work on it to bring it up to the standard that I want it to be, and that’ll be great as it’s been hanging around. Actually, this interview has made me realise that much of what I’ve done hasn’t been documented and that really need to change! PB: And ironically, we’ve come full circle from Sermon Records [Strangelove’s first record label] to ‘Seven Sermons for the Dead’. PD: (Laughs) Very good. I’ve never noticed that before. PB: There’s always a circle. You had a song called ‘Circles’, didn’t you? PD: Yeah, I didn’t realise that. Thank you. PB: Patrick, thank you for one of the most honest and captivating interviews I’ve ever done. PD: Thank you. Thank you very much.

Band Links:-

https://www.facebook.com/PatrickDuffArtist/https://twitter.com/patrick_duff

Picture Gallery:-

interviews |

|

Interview Part 1 (2011) |

|

| In the first part of a two part interview, Bristol-band singer-songwriter Patrick Duff talks about to Denzil Watson about his tormented, but seminal 1990's alternative rock act, Strangelove |

| Interview (2010) |

live reviews |

|

Greystones, Sheffield, 24/3/2019 |

|

| Denzil Watson witnesses a raw and intimate Sheffield gig by former Strangelove frontman Patrick Duff. |

| Barfly, London, 10/3/2006 |

reviews |

|

Luxury Problems (2005) |

|

| Eclectic, experimental first solo album from former Strangelove frontman, Patrick Duff |

most viewed articles

current edition

John McKay - InterviewRobert Forster - Interview

Cathode Ray - Interview

Spear Of Destiny - Interview

Fiona Hutchings - Interview

When Rivers Meet - Waterfront, Norwich, 29/5/2025

Carl Ewens - David Bowie 1964 to 1982 On Track: Every Album, Every Song

Chris Wade - Interview

Brian Wilson - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

Shrag - Huw Stephens Session 08.12.10 and Marc Riley Session 21.03.12

previous editions

Heavenly - P.U.N.K. Girl EPBoomtown Rats - Ten Songs That Made Me Love....

Allan Clarke - Interview

Oasis - Oasis, Earl's Court, London, 1995

Manic Street Preachers - (Gig of a Lifetime) Millennium Stadium, Cardiff, December 1999

Barrie Barlow - Interview

Pixies - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

Beautiful South - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

Trudie Myerscough-Harris - Interview

Dwina Gibb - Interview

most viewed reviews

current edition

Peter Doolan - I Am a Tree Rooted to the Spot and a Snake Moves Around Me,in a CircleGarbage - Let All That We Imagine Be The Light

Vinny Peculiar - Things Too Long Left Unsaid

Vultures - Liz Kershaw Session 16.06.88

John McKay - Sixes and #Sevens

Little Simz - Lotus

HAIM - I Quit

Morcheeba - Escape The Chaos

Pulp - More

Lapsley - I'm a Hurricane, I'm a Woman In Love

Pennyblackmusic Regular Contributors

Adrian Janes

Amanda J. Window

Andrew Twambley

Anthony Dhanendran

Benjamin Howarth

Cila Warncke

Daniel Cressey

Darren Aston

Dastardly

Dave Goodwin

Denzil Watson

Dominic B. Simpson

Eoghan Lyng

Fiona Hutchings

Harry Sherriff

Helen Tipping

Jamie Rowland

John Clarkson

Julie Cruickshank

Kimberly Bright

Lisa Torem

Maarten Schiethart