Mary Gauthier - Interview

by John Clarkson

published: 29 / 7 / 2010

intro

American folk musician and adoptee Mary Gauthier talks to John Clarkson about her much acclaimed sixth album, 'The Foundling', which was inspired by her failed attempt to contact and meet with her birth mother.

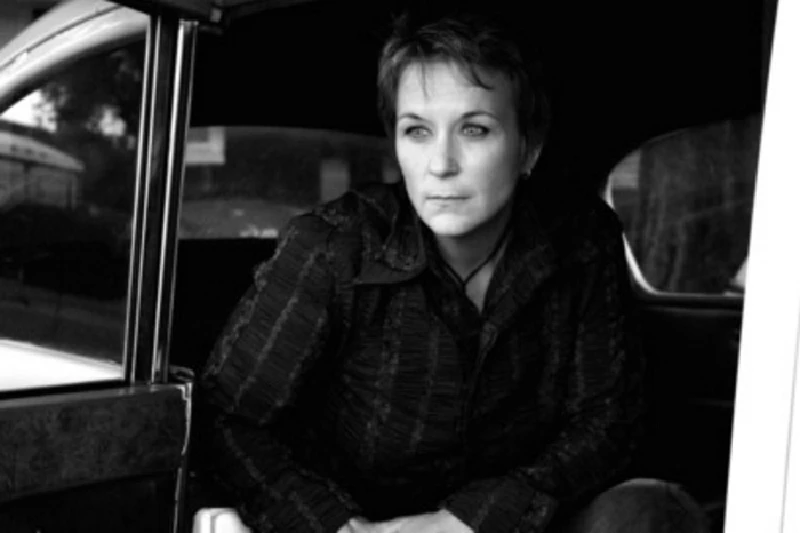

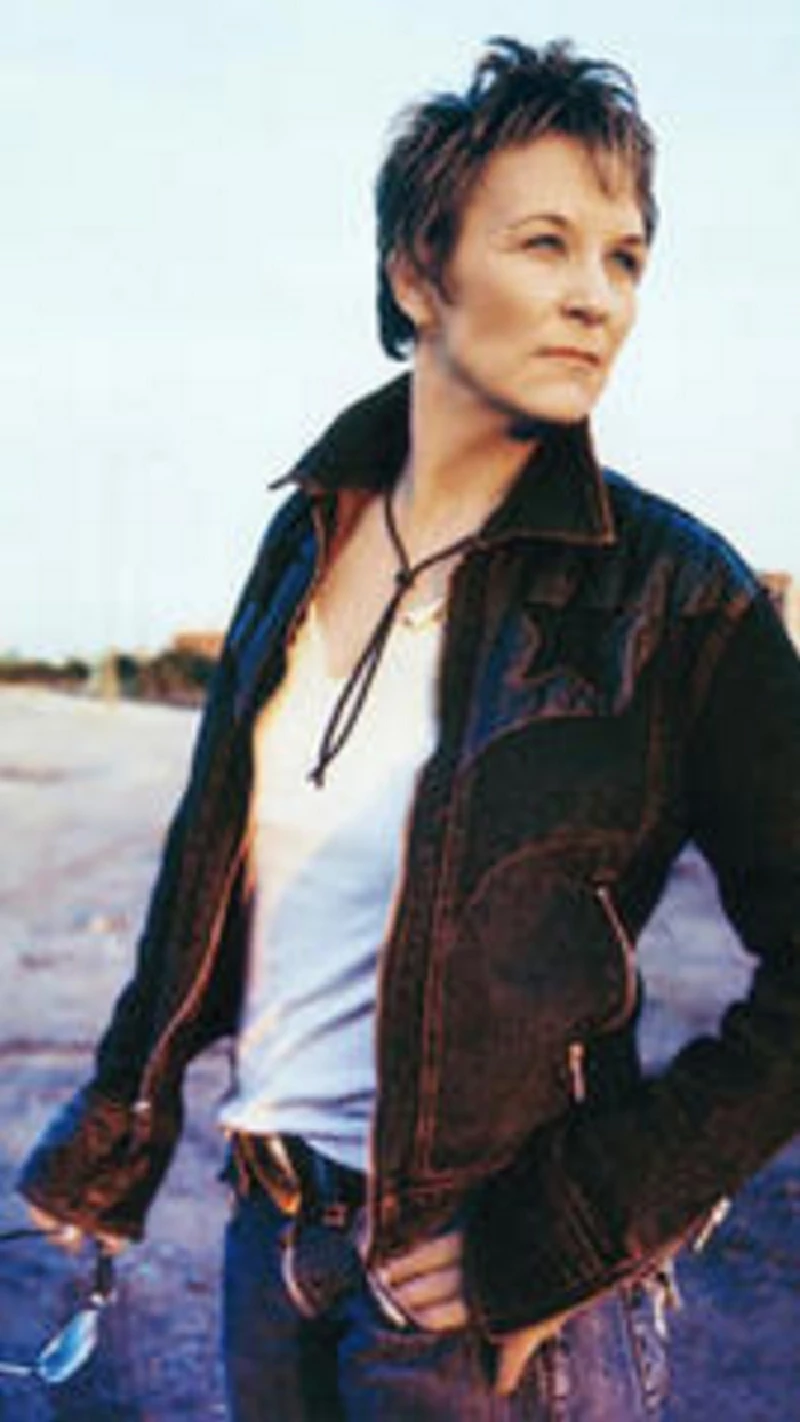

American folk musician Mary Gauthier has developed a reputation for frank honesty and openness in her intensely personal and autobiographical song writing. Gauthier, who was born in New Orleans in 1962 and now lives in Nashville, did not write a song until she was 35. Her troubled upbringing and unstable twenties and early thirties have since then provided her with the inspiration for much of her material. She has told over the course of five previous albums with a raw lack of self-pity of her struggle to come to terms with being a lesbian, subsequent battle with both drink and drugs, and also of her teenage skirmishes with crime which saw her seeing her eighteenth birthday in inside a police cell. When one looks deeper into Gauthier’s background, it becomes perhaps apparent why she had such a traumatic coming-of-age and earlier life. The daughter of a young and unmarried mother, Gauthier spent the first year of her life in a Catholic orphanage, before being adopted by a Baton Rouge couple who she has since described as being “Italian, Catholic and doomed.” Her adopted father was an alcoholic, the mother suicidal, and this volatile home situation lead to Gauthier stealing the family car and running away from home at the age of fifteen. ‘The Foundling’, Gauthier’s sixth and most recent album, breaks new ground and is possibly her most soul-searching record to date. Her first concept record rather than a loose set of songs, it tells of Gauthier’s adoption and how at the age of 45 she searched for and found her birth mother. Her birth mother had been married and widowed and had two other children, but had never told her family that she had another child. In a phone call with Gauthier, she denied her a meeting. ‘March 11, 1962’, the central song on the album, recollects that phone call. ‘The Foundling’ features Gauthier on acoustic guitar and there is also accordion, fiddle, keyboards and a trombone. It was produced by Michael Timmins of the Cowboy Junkies in Toronto, and as might be expected of Timmins’ work, is both typically sparse and mournfully beautiful with Gauthier’s rough-twanged voice serving as the record’s main instrument. There are guest appearances from Timmins’ sister and fellow Cowboy Junkie Margo Timmins on backing vocals, and The Band’s Garth Hudson, who lends his breezy piano-playing, to one song, ‘Vaudeville’. Despite its painful subject matter, Pennyblackmusic found Gauthier in an interview about ‘The Foundling’ to be at terms with the past. PB: ‘The Foundling’ must have been an emotionally harrowing album to write. Was there any point when you thought that you couldn’t continue with it and that you wanted to stop? MG: No. The process of writing it was a real challenge. It wasn’t a challenge though because of the subject matter. I had already lived through it and all the emotions around that. The challenge was putting the stuff together so that they added up to a big story. I had never really written in that kind of structure before and done a concept album. It was almost like writing a book or a musical. It wasn’t just a matter of getting inspired and writing a series of songs. I had to write songs so that they added up to a story or a big theme. It took a lot of effort and about two years to do it. PB: Is it true that some of the songs such as ‘Goodbye’ were written before you began your search for your birth mother and others after you had found her? MG: Yeah, ‘Goodbye’ was written before I had even never thought about searching for my birth mother. It appeared originally on my 2002 album, ‘Filth and Fire’, but it just seemed like it belonged on this record as well. It seemed like it needed re-recorded. I felt like I cut it too fast when it was on ‘Filth and Fire'. Peter Rowland was on the original playing mandolin and it kind of developed a bluegrass sound, which isn’t a bad thing. It’s not exactly a happy song though, so it needed to go into the right tempo for the meaning to be conveyed and it just fitted this song cycle so greatly that I felt that it should be re-recorded. Since I felt like I missed it the first time around and it fits this cycle so well, I wanted to see if we could catch it and I felt like we finally did. PB: Were there any other songs on ‘The Foundling’ that you recorded twice? MG: No, that was the only one. PB: Did a particular turning point come when you decided to write an entire set of songs about being adopted? MG: Inspiration is a funny thing and I knew for years and years and since I became a songwriter that one day I would write a record called ‘The Foundling’. I just knew it. I hadn’t lived through the process of understanding my story long enough to be able to write it, and quite frankly I wasn’t a good enough writer yet. I had to write several records and do a lot of work to get to the place where I was capable of writing at this level. It was not easy and was a very challenging thing to do. PB: There is a law in the States that does not entitle an adoptee to a birth certificate, which is something that you have campaigned actively against. How easy was it for you as a result of that to find your birth mother when you decided to begin the search for her? MG: It was quite difficult. The birth certificates of adoptees are held by the state and adoptees are denied access to their own birth certificates. That is the law and that is just the way it is, so if you want to go and find your birth parents or your birth mother you have to get a private detective to start looking for clues. It took me a couple of years to figure out that what I needed to do was contact a Catholic charity and ask them who the private detectives were that they worked with. They put me in touch with someone that they had worked with before and once I got the right private detective it took three days. It was very, very fast at the end. I figured that it would be a few months before I found out. It just took three days though and then I had the name of my mother in my hand. PB: How long after that did it take you to phone her? MG: Six months. It was a very hard phone call(Laughs). PB: You capture that on the album and ‘March 11, 1962’ in particular just how difficult that phone call was. MG: I think part of me knew that it wasn’t going to go the way that I hoped that it would. I sort of knew that it wasn’t going to be what I was hoping for which was for her to be someone that I could be friends with. She was just too heavily traumatised and it has been extremely difficult for her. PB: Have you had any contact with her since? MG: No. PB: On ‘March 11, 1962’ you describe the phone conversation that you did have with her. It took six months for you to make the phone call. How long did it actually take you to write that track? MG: That was the fastest song that I have ever written. It took five minutes. I wrote it with my friend Liz Rose actually, who co-writes with Taylor Swift as well if you can believe that. She writes with both Taylor Swift and me (Laughs). Liz came over and we were having a dinner party and people coming over and she said, “Let’s just write this thing while we wait for everyone to arrive” and I swear we hit the last chord and last word when the doorbell rang. It was unbelievable. I have never written a song that fast and I bet that I will never write another one again that quickly. PB: How long after making the phone call did it actually take for that song to come together? MG: A long time. It was over a year. That song was the exact replication of that phone call. To the best of my memory that was how it went. PB: ‘Walk in the Water’, the track which follows it, seems more double-edged. It could be about the end of a romance. Was that what it was originally written as? MG: Yes, and then I realised that all my romances have been with my mother, both my missing mother and the mother that had adopted me. All my romances have led there. There are such parallels that it is startling. Either that or I have had too much therapy. I am not sure which (Laughs). That was written at the end of a romance, but then I realised that same grief could be applied to letting go of my birth mother. It could have been written about my dog. If the loss is profound enough, then the grief process is going to be very similar. PB: Was that song written again before you wrote much of the other material on the album? MG: Yes. That was another one of the earlier songs. PB: There seems to be sense of irony pervading a lot of the album. ‘Mama Here, Mama Gone’ is almost like a lullaby and is the sort of tune a mother might sing her baby to sleep with, while ‘Sideshow’ has an old-fashioned Vaudeville feel to it, but it is written from the perspective of someone who feels that they are a complete freak of nature. Was that irony something that you worked consciously towards when you were writing this album? MG: Absolutely. There is a sardonic humour on a lot of this album. There is some heavy material there. I am not really by nature that sombre a person though. There is humour as well. Some of the greatest comedians of all time fall from pathos and there has got be a balance. On both of those songs there is a little bit of balance between tongue-in-cheek humour and truth. The truth is that I really don’t like happy songs, especially when there are twenty in a row like on country radio in the United States. There is no way that I can listen to that. It makes me crazy and uncomfortable. You’ve got to be high to listen to that. It’s unlistenable. It is totally out of my reality. PB: It is in a lot of ways a dark album, but it ends on a note of hope with the song ‘Another Day Borrowed’ and the line on that in particular “Wild and worn/I’m hanging on/To another day borrowed.” Was it important to you to finish on a note of tentative optimism? MG: In order for it to be true I had to. I am doing actually quite well. In my whole life I have never been more at peace and more whole and so it would not be honest if I didn’t take it to the place where I am now. I do see things though as every day borrowed. We’re borrowing time. Nobody owes us anything and I guess the place that I wanted to end it on was a place of humility. PB: What do you mean by the line at the very end of that song, “Me, I’m almost ready”? MG: I think that I meant that I am almost ready for love. I am almost ready to make that plunge and to have a real relationship. I think that is what literally I meant, but what I do know? So many things when you are a songwriter are mysterious. I think that it meant though that I am ready for the higher ground. I have been down here at the bottom and I have been dealing with this stuff for a while and this is it. I am done. I have dealt with it. I am moving on. Here’s my story. I am done. This isn’t my story anymore in terms of living. I have lived it. I am moving on. The challenge was to get the story. That is the challenge for an adoptee, to get the story because we live in such shrouded mystery and with so many secrets, so many lies,so many myths. Just to be told that your mother gave you away because she loved you so much, that twists the head of a kid around. Of course it ultimately makes sense. Sacrifices were made so that I could have a good life, but I had to embrace that as an adult and work through all kinds of stuff and a lot of layers. I do have a good life now and that is where I wanted to end this story which is more than just a story obviously. It is my life. PB: You have described Willie Nelson’s 1975 album,‘Red Headed Stranger’, as being “a compass” for this album. That is about a man who goes on the run after killing his wife. In what way did that serve as a blueprint for this record? MG: First of all it is a brave record, especially in the context of the time that it was put out. When he turned that record in, the record company said, “Nice demos. Where is the record, Willy?” and he said, “That’s the record. Take it or leave it.” It is about a man who kills his wife and who goes on the run, but the brilliance of it is that he turns it around and makes it a love story in the end. The brilliance of that writing inspired me. Plus it was the first country concept record ever written and it was educational just in that it had been done in a genre that had never been done before. PB: Both Michael and Margo Timmins have adopted children. Was that one of the factors for getting them involved in the making of the album? MG: It sure helped. It helped because we understood each other, them from the adopted parents’ perspective and having compassion for their kids. We were able to talk about things that transcended beyond the studio and just recording a record. PB: Were there any other factors as well in why you decided to go with them for this record? MG: Yes, the minimalism that Michael exhibits in his recording and producing. I am a sucker for a minimalism. I always feel less is more. He just understood intriniscally that this album was about the words. PB: How long did the album actually take to record? You are in Nashville and the album was recorded in Toronto where the Timmins are. Did you have to go back and forth there a lot? MG: Yeah, I went back and forth quite a bit because we are both touring acts. When we weren’t on the road, we were cutting it. It took about six months I think. PB: You have been touring a lot. What has been the reaction from adoptees and both birth parents and parents of adopted children to the album? MG: It has been amazing. The reaction that I have been getting from the songs is that people want to tell me their story. They are shocked that someone is telling them a close approximation of their own story and so they want to return the favour and tell me their story. I am getting stories from everywhere. My e-mail box is full of stories, stories, stories. I did a national public radio piece about it in the US last week. I probably have fifty or sixty stories that have been sent to me. I don’t know what to do with them. At some point it should be a book or something. I have found myself in a position of quick intimacy with people and it is a kind of sacred place to be. PB: You’re in a position of some authority with this, aren’t you really? MG: I really want to listen to people and to hear what they have to say. A lot of the time the telling of your own story when it comes to adoption can be a healing thing. It can be a step back towards your own strength. What I am working on now is trying to figure a way so that people can come and tell their stories to each other because obviously I can’t go and shake hands with everyone’s story. I am thinking about it now and trying to work it all out. PB: You are working on a memoir as well. MG: Yeah, I am about eight chapters in on it. I am calling it creative non-fiction. I don’t really know if I am telling the truth, because my memory is as suspect as anyone’s and certainly a memoir implies that it is all true. I am just doing the best that I can to remember and to tell the story that happened. The tail-end of it will be me coming to write this record and how I have got to the place where I am able to tell this. Most people expect it to be a really heavy and huge challenge for me to go out and play these songs every night, but it is not. It actually feels light around me and that is this story, how I got there. I am lighter now, both emotionally and spiritually than I have ever been. PB: The issue of adoption is often tackled by the media in a very sugar sweet way. This album seems to take a more realistic approach to it. It is a very brave album in that respect. MG: Thank you for that observation. People don’t want to know about the struggle and how hard it really is. People don’t want to see it as a trauma, but it is a trauma. It is not a trauma that you can’t overcome, but there is an inherent trauma in taking a baby away from a mother and on both parties’ parts. Both people carry that with them for the rest of their life and we don’t want to acknowledge or accept that or believe that. It is, however, the truth. The truth will also set you free though because the more you tell these stories the more people will be able to live in reality and be set free of some of this stuff. PB: What will you do next musically, Mary? MG: I don’t know. That is the question every journalist asks me. I have a feeling that I should buy an electric guitar and do some rock ‘n’ roll now (Laughs). I feel this liberation at the moment and I might even be writing happy songs, God help me. The muse will tell me though. I am sure that she is still in charge. PB: Thank you.

Band Links:-

https://www.facebook.com/marygauthiersongshttp://www.marygauthier.com/

https://twitter.com/marygauthier_

Picture Gallery:-

soundcloud

reviews |

|

Rifles and Rosary Beads (2018) |

|

| The most important album of the year so far from Mary Gauthier co-written with U.S. veterans and their families as part of the Songwriting With: Soldiers program |

| Trouble and Love (2014) |

| Live at Blue Rock (2012) |

| The Foundling (2010) |

most viewed articles

current edition

Carl Ewens - David Bowie 1964 to 1982 On Track: Every Album, Every SongColin Blunstone - Thalia Hall, Chicago, 16/7/2025

Visor Fest - Valencia, Spain, 26/9/2025...27/9/2025

Editorial - July 2025

John McKay - Interview

Billie Eilish - O2 Arena, London, 10/7/2025

Hothouse Flowers - Photoscapes

Bathers - Photoscapes 2

Bathers - Photoscapes 1

Cleo Laine - 1927-2025

previous editions

Heavenly - P.U.N.K. Girl EPBeautiful South - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

Trudie Myerscough-Harris - Interview

Pixies - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

Boomtown Rats - Ten Songs That Made Me Love....

Fall - Hex Enduction Hour

Sam Brown - Interview Part 2

Doris Brendel - Interview

Jimmy Nail - Interview

Blues and Gospel Train - Manchester, 7th May 1964

most viewed reviews

current edition

Amy Macdonald - Is This What You've Been Waiting For?Sick Man of Europe - The Sick Man of Europe

Alice Cooper - The Revenge of Alice Cooper

Phew, Erika Kobayashi,, Dieter Moebius - Radium Girls

Lucy Spraggan - Other Sides of the Moon

Blueboy - 2

Cynthia Erivo - I Forgive You

Davey Woodward - Mumbo in the Jumbo

Lapsley - I'm a Hurricane, I'm a Woman In Love

Philip Jeays - Victoria

Pennyblackmusic Regular Contributors

Adrian Janes

Amanda J. Window

Andrew Twambley

Anthony Dhanendran

Benjamin Howarth

Cila Warncke

Daniel Cressey

Darren Aston

Dastardly

Dave Goodwin

Denzil Watson

Dominic B. Simpson

Eoghan Lyng

Fiona Hutchings

Harry Sherriff

Helen Tipping

Jamie Rowland

John Clarkson

Julie Cruickshank

Kimberly Bright

Lisa Torem

Maarten Schiethart