Robert Wyatt - Robert Wyatt

by Jon Rogers

published: 25 / 6 / 2010

intro

With 'His Greatest Misses' a new compilation of his work out, Jon Rogers reflects upon the idiosyncratic solo career of musicians' musician and former Soft Machine member, Robert Wyatt

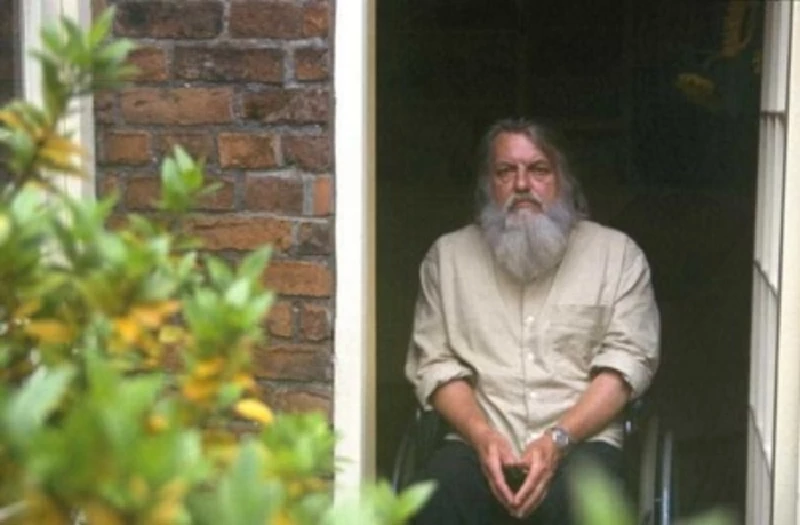

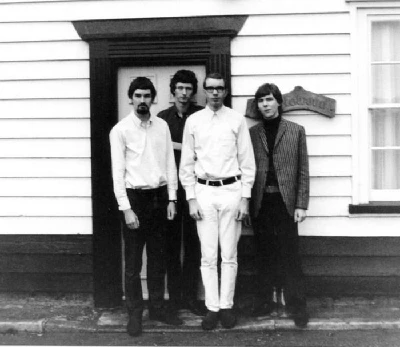

Robert Wyatt-Ellidge, born on 28 January 1945, is something of the musicians’ musician. His various albums haven’t propelled him to the top of the charts and haven’t sold in huge numbers, but the list of people he’s worked and collaborated with is impressive. For starters let’s just namedrop the likes of Jimi Hendrix, Paul Weller, Brian Eno, members of Pink Floyd (and Nick Mason in particular). Not quite convinced? How about Björk, Hot Chip and Billy Bragg? An overview of Wyatt’s musical career would be quite something, spanning his time as drummer with Soft Machine, the 60s underground avant-garde group that was the house band – along with Pink Floyd – of the UFO club. There’s the experimental, jazzy Matching Mole let alone his extensive solo albums. The closest he’s come, really, to having a hit was with his idiosyncratic interpretation of the Monkees’ ‘I’m a Believer’. This correspondent still can’t tell if he’s taking the piss... or whether he’s deadly serious. To be fair, it’s probably a bit of both. And perhaps idiosyncratic is the key here, Wyatt is something of an acquired taste. His beautiful, fragile voice often telling of his love for his wife Alfreda or getting riled up over some political issue – Wyatt is staunchly left wing with a Marxist/Communist streak. And how many pop stars bother to write a song discussing free will in the form of ‘Free Will and Testament’? And the highly-acclaimed, rather eccentric ‘Shleep’ is a long way from the psychedelic, free-form, jazz doodling of the William S Burroughs inspired Soft Machine. Wyatt’s musical and cultural education seems to have started with his parents and in particular his father who suffered from multiple schlerosis. He told ‘Mojo’ in 1999: “I really liked my dad’s records and paintings and stuff he liked, which was the avant-garde of the first half of the [twentieth] century. Picasso, Prokovieff. So that was a sort of starting point, but it was already a nostalgia for an imagined world that my dad lived in. And even when I got into bebop and modern jazz in the fifties, it was already nostalgia for an imaginary Harlem.” And Wyatt, fairly early on in his drumming career got to play with guitar legend Jimi Hendrix. After the Soft Machine had toured the USA supporting Hendrix in 1968, Wyatt stayed on in the country and then got invited down to jam with the Jimi Hendrix Experience at TTG Studios in Hollywood in October 1968. “To me, as someone who’d spent much longer listening to the glorious disintegration of bebop into Sun Ra and Charlie Haden and Don Cherry, this felt more comfortable to me than the strict time and neat and tidy blocks of sound that rock music was locked into. The music breathed, it had air in it. Of course bits floated off and got lost, but that suited me fine.” At the end of the tour Hendrix’s regular drummer Mitch Mitchell gave Wyatt his Maplewood kit, which he still has. “He was pure light,” said Wyatt, referring to Hendrix. “I did see him every night playing something like ‘Red House’, and every night it just made the hairs stand out on the back of your neck. I feel quite tearful about it, even now.” And it is impossible when discussing Wyatt’s work not to give a prominent position to his Spanish wife, poet, artist and close collaborator Alfreda Benge. Not only are virtually all the covers of his solo albums designed by her but her input is essential, often contributing poems or lyrics as well as words of encouragement or advice when something doesn’t quite work. As Wyatt put it in 2001 to ‘Ways of Hearing’: “She and I are a group of two really. Nearly all of Alfie’s poems or lyrics that I use are written about experiences that I’ve shared with her.” The dress rehearsal for Wyatt’s solo career took place in August 1970 with the album ‘The End of an Ear’, after Wyatt had effectively taken a sabbatical from Soft Machine after internal disagreements. He would actually go on to leave the group the following year. Despite a few flashes of interests it could only garner a rather muted response and is perhaps best left for the curio box of a time – and musical style – now long past. It mixed up free jazz with tape experiments and didn’t have any lyrics, just Wyatt’s vocal experiments. Hmm...That experimental stance, however, was necessary for Wyatt as he reflected years later. “I learned a lot doing it. It was the first time I had ever really gone into the studio and just treated the tape as a canvas upon which to paint, so just that feeling was incredibly exciting and very euphoric and it also broke my fear and intimidation of keyboard players. I had to play so much piano for example and that broke the ice in terms of playing me own piano bits.” According to Alfreda Benge, Wyatt leaving Soft Machine was one of those ‘did he jump or was he pushed’ moments. Either way though he wasn’t part of the group anymore and that dented his confidence so badly that, apparently, for years after he suffered from a recurring dream where he was playing badly on stage and jazz trumpeter Miles Davis was in the wings sniggering. Having finally left Soft Machine he set up his own band Matching Mole (the name a pun on the French term for soft machine, machine molle). The group was largely an instrumental one and once again in the avant garde vein, if not quite as much as his first solo album. Internal arguments tore the band apart but plans were afoot to make a third album when disaster struck Wyatt on 1 June 1973. During a party at June Campbell Cramer’s Maida Vale flat, an inebriated Wyatt fell from a fourth-storey window, paralysing him from the waist down and putting him in a wheelchair. Any hopes of continuing to drum for Matching Mole were dashed. It’s perhaps no surprise that Wyatt was good friends with John Peel and his wife Sheila and it’s perhaps a testament to their friendship that Robert and Alfie were the only Arsenal supporters Peel allowed into the house until the mid-1990s. Wyatt was there at the first ‘Top Gear’ (the name of Peel’s then radio show) Christmas carol concert in 1970, which along with John, Sheila and Robert also featured Marc Bolan, the Faces and Ivor Cutler all squeezed into the studio for versions of ‘Silent Night’, ‘Away in a Manger’ and ‘Good King Wenceslas’. Peel and Wyatt were constant friends for a number of years and Peel went to visit him after his accident in 1973 when he was recovering at Stoke Mandeville hospital. At the time he wrote in his diary: “There’s something about Robert – a sort of questing, wide-eyed-innocent-abroad quality – that has always made the Pig [Peel’s affectionate name for Sheila] and I feel very protective towards him. Supremely silly, really, as he’s invariably shown a capacity for coping with and adjusting to traumatic changes of circumstances much better than I could [...] When I rather condescendingly trotted out this weighty tripe, he quickly disabused me by observing that much worse things had happened to him in his life and his sole philosophy as far as his accident went was ‘hum, bloody typical!’ He’s a man for whom the Pig and I have a considerable respect and affection.” Wyatt’s determination to not let a mere a disability get in the way of things soon appeared and ten months after Peel and visited Wyatt in hospital, Wyatt launched his solo career with a four-song session for Peel’s show, including a stripped-down version of ‘I’m a Believer’. Whilst recovering in hospital Wyatt formulated his next – and possibly greatest – solo album ‘Rock Bottom’ which eventually saw the light of day the following year. ‘Rock Bottom’, despite the rather woeful and punning title, lacked any sort of self-pity while being deeply personal and portrayed a wounded and vulnerable Wyatt. ‘Rock Bottom’ is an unassuming album but demands your attention which sees a contemplative Wyatt for obvious reasons. But along with that there’s Wyatt’s strong streak of English eccentricity and playfulness, such as titles like ‘Little Red Robin Hood Hits the Road’. It also contained a rather nonsensical narrative from his friend Ivor Cutler. Wyatt has denied though that his accident had little or no bearing on the album citing that most of it had been written in Venice prior to the accident. That element of humour and playfulness is important to bear in mind. Lou Reed’s ‘Berlin’ is perhaps equally depressing but doesn’t contain many laughs. At times Wyatt can be cheesy with his puns but they still raise a smile. ‘Rock Bottom’ is far from a happy album but it is an uplifting one. The album is up there though with the great post-psychedelic albums like Tim Buckley’s ‘Starsailor’ and CAN’s opus ‘Tago Mago’ as well as the more inspired moments from Miles Davis’ electric period like ‘Live-Evil’ or ‘Dark Magus’. ‘Rock Bottom’ was also, in part, Wyatt’s reaction to what he saw as the then moribund state of the British music scene – and particularly rock drummers. “That heavy 4/4 thing they’re [the drummers] all using now doesn’t strike me as having much in common with the fluid, loose, danceable rhythms you get in R&B,” he moaned to ‘NME’ in July 1974. “It reminds me more of military brass bands, and in fact, most British drummers these days sound as if they’ve come straight out of the army to me.” For a pacifist Wyatt, this wasn’t a compliment. For Wyatt, what was interesting to him was the “hit parade” and what he saw as its “crazy logic”. “It’s largely beyond me,” he commented. “Why one three-minute chunk makes it while another doesn’t.” The thing is, Wyatt would also find himself in the “hit parade” with his version of ‘I’m a Believer’ which went Top 30 and got him a slot on ‘Top of the Pops’. It nearly didn’t happen though thanks to the show’s Robin Nash deeming Wyatt’s appearance in a wheelchair on the show as “distasteful” for the audience. Understandably Wyatt objected, causing a minor fracas which was ultimately resolved in Wyatt’s favour. Capitalising on his profile, Wyatt didn’t waste any time in producing his follow up album ‘Ruth is Stranger than Richard’ which was released on 1975. The album’s feel is much more open and freer than ‘Rock Bottom’, mixing in original pieces as well as covers like Charlie Haden’s ‘Song for Ché’. The album harks back more to Wyatt’s Soft Machine days and has a jazz-rock feel with its open structures and improvisations. There’s the four-part, jazzy ‘Muddy Mouse’ and the blues-like shuffle of ‘Soup Song’. Adding a small, but significant, part was Wyatt’s friend Brian Eno who had popped down to the Manor studios in Oxfordshire where Wyatt was recording before heading off on tour with Robert Fripp. Wyatt had assembled a cross-section of musicians ranging from bass player Bill MacCormick who had played in Matching Mole, to Pink Floyd’s Nick Mason who was producing as well as various people from the Canterbury scene and also jazz musicians like trumpeter Mongezi Feza and saxophonist Gary Windo. According to MacCormick there was a bit of tension between the jazz musicians and the others who considered jazz to be “crap”. The point is highlighted on the song credits to ‘Team Spirit’ where Eno is dubbed to have added “direct injection anti-jazz ray gun guitar”. Eno and Wyatt had become almost instant friends during Wyatt’s spell in Matching Mole and Eno had contributed synthesizer to the band’s ‘Little Red Record’ after they had met at an exhibition of Peter Schmidt’s paintings. They became firm friends: “We started meeting just socially, playing Scrabble, chatting about this and that, Wyatt recalled. “It’s always fun with Brian. Alfie and I liked him so much. He was always a welcome visitor.” Along with all the musicians on that album was one actress Julie Christie, who had just finished filming the thriller ‘Don’t Look Now’, who contributed some monologue vocals. After ‘Ruth is Stranger than Richard’ Wyatt took something of an extended sabbatical from his solo career but could be found popping up on other people’s records every now and again and generally keeping his hand in with the general music scene in London. Although Wyatt was slightly disconnected as at the time he lived out in Twickenham, one house guest for a while was the former Velvet Underground chanteuse Nico. She was in London to record her latest collection of gothic hymnals, ‘The End’. Although the two knew each other already, on one side was the down-to-earth, communist Wyatt whilst Nico had acted in Fellini’s ‘La Dolce Vita’, had been a lover of the Rolling Stones’ Brian Jones and French film star Alain Delon as well as having had a fling with Jim Morrison from the Doors as well as being a muse for Bob Dylan. The circles Nico moved in were rather more glamorous than Wyatt’s. Fortunately for Wyatt Nico’s heroin habit hadn’t yet fully taken control of her so she wasn’t much trouble. Eno and Wyatt continued to work together over the years with Wyatt making a brief appearance on ‘Taking Tiger Mountain by Strategy’ and Wyatt would be consulted when Eno was launching his Obscure label. One project that ran out of steam was the idea of a collaboration that would not only involve Eno and Wyatt but also Phil Manzanera, one time Roxy Music member along with Eno, but due to largely financial problems the project never saw the light of day. One collaboration that did bear fruit was Eno’s album ‘Before and After Science’ in 1977 with Wyatt being credited as one Shirley Williams, the then Secretary of State for Education. The album had an all-star cast. Along with Manzanera there were amongst others Phil Collins, Jaki Liebezeit and Robert Fripp. Perhaps the most significant collaboration between Wyatt and Eno though was the ground-breaking ‘Music for Airports’. Eno had mentioned the idea of creating soothing airport music to Wyatt previously but Wyatt was also roped into the sessions at Basing Street studios with Wyatt also getting an co-writing credit on the opening track ‘1/1’. Wyatt’s role, largely, though was to play spontaneously on the piano. “Brian just sort of got me to improvise at the piano for a while and chose what to use later,” Wyatt recalled. “I was surprised and delighted with his use of what I did – how he created a sustained mood. I didn’t know what he would do with what I’d played. I think the results were brilliant, pure Brian: great stuff!” The two have been firm friends for years with Wyatt telling David Sheppard: “Brian Eno is one of the only people I’ve worked with who I can actually say I love.” Wyatt tentatively resurrected his solo career in 1980 with the release of a single featuring two South American songs of liberation which marked the start of his most political period. Wyatt had always held strong left-wing political beliefs but now they were to the fore. The move also marked a change of label for Wyatt with him being lured by Geoff Travis, owner of Rough Trade, after the two had met thanks to a mutual friend Vivien Goldsmith. By now Wyatt was a Communist party member which no doubt fitted in nicely with the left-leaning, co-operative stance of the label. Travis got Wyatt out of his existing contract with Virgin but with the proviso that he didn’t release an album immediately, hence the spurt of singles. While Wyatt claimed not to have even known what “indie” was at the time, telling Rob Young for his history of the label that he thought it was something to do with the “Bombay film industry”. Instead of reading the UK music press he’d had his nose inside ‘The Morning Star’. He had, however, still been listening to a wide variety of music from free jazz and bebop to disco and soul as well as folk music from around the world. The first single for Rough Trade was a cover of ‘Arauco’ by the Chilean songwriter and activist Violetta Parra. Chile was a major political concern to Wyatt – the democratically elected government had been violently overthrown by General Pinochet, with the help of the CIA, in 1973. Two other singles followed. Next was a version of the 1940s song ‘Stalin Wasn’t Stalin’’ which was from a time when the Soviet Union and USA were united against the threat from Nazism. At the time there was no such thing as the Cold War. The trilogy was completed by ‘At Last I Am Free’, a cover of a Chic song, which in Wyatt’s hands became a song of self-liberation. All three would later be gathered together for the album ‘Nothing Can Stop Us’ and amounted to a political tract from Wyatt albeit one with a very personal dimension. “I never associated shouting at people with making the world a better place,” he told Young. “You couldn’t not be acutely aware of street politics at the time, and not feel a solidarity in the face of hostility from the state, whether it’s miners or Rastas or anybody else. I felt that was very much the dark side of the punk moon, if you like, the whole black experience – which is sort of ignored internationally when punk is discussed.” The title of the album came from a quote by American Ludwell Denny in 1930: “We shall not make Britain’s mistake. Too wise to try to govern the world, we shall merely own it. Nothing can stop us.” These singles were then enhanced by the timely release in 1982 of the Elvis Costello and Clive Langer-penned the anti-war ‘Shipbuilding’ which had been specifically written for Wyatt. It was to be, pardon the pun, Wyatt’s high-water mark in his career. The lugubrious song painted a bleak portrait of a down-at-heel port living on the hope that one day its dockyard would be revived but never does quite happen. The plaintive song caught the mood of the nation under a conservative administration led by Margaret Thatcher that had introduced austere financial measures and set about taking on the power of the trade unions. The mood of nation though had been injected with patriotism when the prime minister sent a taskforce to the Falkland Islands to see off an Argentinian invasion. “I got a cassette through the post,” remembered Wyatt. “They [Costello and Langer] they’d done this song they thought might suit my voice more than the groups they were working with at the moment. Would I have a go at it? And I thought, blimey, what an honour. Because one of the things I expected was to be hardly allowed in, because of the expected hostility to long-haired people of the previous musical generation. I was surprised how friendly and welcoming they were to me, compared to the subsequent generation. “Anyway, I learnt it. Went to the studio with Costello, and recorded it. He made me do it right. It was one of those cases where I wasn’t smoking, so my voice was more on top of it than it might have been.” The initial idea was to release the song on a new label set up by Costello, but Wyatt thought to do that would be “dishonourable” to Travis and opted for Rough Trade instead. The song, which made the charts, should have been a huge hit. Not only did it capture the mood of the nation but also had a big name appearing on it in the form of Costello. As Wyatt, however, remembers, “Everyone got too excited and then made a video that cost more than the records sold. So in fact it’s my least successful record.” Wyatt was also heralded by the younger, supposedly hipper Rough Trade generation at the time and made guest appearances on the Raincoats’ second album ‘Odyshape’ as well as Scritti Politti’s single ‘The Sweetest Girl’, the band being big fans of his. He also made a guest appearance on Ultramarine’s album ‘United Kingdoms’ in 1994 who had also been long-time fans of both Wyatt and Kevin Ayer. Wyatt also found time to make two more records for Rough Trade, ‘Old Rottenhat’ in 1984 and ‘Dondestan’ in 1992. The latter was an adaptation of the Spanish ‘Donde estan’, meaning ‘where are they?’ Both albums, while not quite portraying Wyatt on top form still remained compelling and impressive and showed that he’d not lost any of his political bite. ‘Dondestan’ holds particular importance to this writer as at the time of its release I was working at Rough Trade and had been given the task of sorting out a series of interviews. I phoned the number I’d been given to sort out convenient times and just dialled the number expecting it to be someone like his agent or manager. A friendly female voice quickly answered the phone and after I’d introduced myself she just went: “Oh, I’ll go and get him...” It dawned on me that I hadn’t been given the number of his manager or someone like that, but that it was his home number and I’d just been speaking to Alfie. Wyatt’s soft, unassuming voice soon came down the line. It was a pleasure to deal with him and times and dates were quickly sorted out before the conversation just fell into having a bit of a chat. I wish I could remember more of what we talked about but I do remember thinking at one point ‘I’m chatting with Robert Wyatt, he sang ‘Shipbuilding’, made ‘Rock Bottom’, was in the Soft Machine. He’s friends with Brian Eno. He was part of the 60s underground scene, played at the famous UFO club along with Pink Floyd... He knew Syd Barrett.’ Even in that brief time it was clear that Wyatt was a genuinely nice person and he’s one of the nicest people I’ve ever had to deal with in the music industry. By now Wyatt had swapped Twickenham for the Lincolnshire countryside and wasn’t quite so fired up, politically. He told ‘Mojo’ in March 1999: “I don’t think it is up to me what people sing about. I mean everybody sings what comes up through their gut and out of their mouth. I never felt that anybody ought to do anything at in that regard. I mean, I was always pleased when people – whether it was Jerry Dammers or Paul Weller – got stuck into an issue. Because they spoke in that understandable language, they didn’t talk obscurely. But it’s none of my business. I mean, I’d have to be some kind of... paedophile to be that interested in youth culture. I’m a bleedin’ grown-up. I listen to grown-up music.” After ‘Dondestan’ Wyatt’s career once again went into a sort of hibernation with only a couple of compilations, like ‘Going Back a Bit: A Little History of...’ in 1994 to keep things ticking over. But he was back on impressive form in 1997 with the wonderful album ‘Shleep’, and once again Eno played a part. ‘Shleep’ was recorded in a similar way to ‘Rock Bottom’ in that had been already mapped out by Wyatt and he knew what he wanted and other musicians would simply come in, “and a bit of virtuosity” (like Annie Whitehead’s trombone parts) and then leave. Essentially their role was to enhance what was already there. They’d come in for a couple of days and work on a particular part. Saxophonist Evan Parker was also called up and he came in and worked with Whitehead and they worked on parts together, adding a Charles Mingus feel to some of the songs, taking their pieces much further than Wyatt had initially imagined. And Weller did a similar thing on ‘Blues in Bob Minor’ – picking up on Wyatt’s original imagined blueprint and expanding on it. “Shleep’ was quite a complicated bunch of pieces,” Wyatt told David Sheppard. “Brian helped in lots of ways – I can’t unstitch it all though – I work in a sort of daydream... I always like to get Brian singing. He composed the wordless bit ‘Heaps of Sheeps’ as a duet. I love singing with Brian, though we haven’t done it a lot.” Overall, the album – as the album title would suggest – had a somnambulistic quality to it and a bewitching, contemplative quality. It was simply his best album since ‘Rock Bottom’. Asked by ‘The Wire’ in September 1997 about why it had taken him so long to make another record, he couldn’t resist a dig at the then prime minister John Major. “The last record I made under me own name was while there was no elected prime minister, and John Major was there by default as it were, I quickly made a record. When he actually got voted in, I was so depressed at the thought that another generation of English people were going to vote for a Conservative government that I went on strike for five years and now he's gone I have made another record. That's what I would like to say, but probably that's a load of old bollocks.” While Wyatt has indulged in the odd side project since there’s only been one other ‘proper’ solo album, the rather neglected ‘Cuckooland’ which appeared six years after ‘Shleep’. The album was, largely, more of the same that could be expected from Wyatt. Gentle drones and genial jazz-tinged songs filled with deceptively strong melodies and all delivered with Wyatt’s now customary almost whispered delivery. At the time both Wyatt and Alfie had become concerned with the growing global problem of rootlessness. He told Andy Gill for an ‘Independent’ interview: “As far as Alfie and I are concerned, the most interesting and poignant situation in the world today is rootlessness and the endless love-hate thing between settlers and nomads that history has been full of. Our tendency is to empathise with the nomads who are often demonised.” And the album was filled with that sort of observation with songs like ‘Lullaby for Hamza’ and ‘Forest’. And popping up on the album were some old friends such as Eno, Weller, Whitehead and Dave Gilmour and Phil Manzanera... Despite the critical praise over the years Wyatt still has a self-effacing quality when it comes to assessing his own work and he often refers to his own songs as “sort of slightly out-of-tune nursery rhymes”. And while his musical heroes might be the likes of Mingus, Coltrane, Davis’ drummer Tony Williams and Nina Simone he has a soft spot for pop music, calling it “the folk music of the post-industrial age” and views his music as conventional pop songs “with long widdly bits on the end, because I’m not very good at stopping.” In an interview with ‘The Wire’ in 1997 he compared his records to being like “Jimmy Somerville on valium”. It’s that self-depreciating wit that endears even on the likes of ‘Rock Bottom’ there’s a lot of little jokes and knowing word play on there to stop it sliding into self-obsessed and self-pitying narcissism. And he can often be found cracking the jokes that “deep down I am shallow” and “what pessimist wants to be right?” But they can’t be so bad if there’s something of a queue of musicians all willing to work with him and all from a variety of musical strands. Along with the Wellers of this world there’s an Evan Parker too, which makes for an eclectic mix. “It’s just that I like all these people and the way they play,” claimed Wyatt in 1999. Sometimes it’s not to do with their genre, but with the character of the particular musician. And it’s the thing I really like about music, and perhaps why I like working with other musicians. Because I like that sense of these characters. I did like that as a jazz fan. The sense of contrast between [John] Coltrane, Cannonball Adderley and Miles Davis – really felt them as people. There’s a particular character trait of someone like Paul [Weller] that I really find appealing, and it gives you an extra musical thing.” Wyatt’s influence has spread far and wide and can still perhaps be most keenly felt in the work of Radiohead, not only in the lyrical intonation of singer Thom Yorke but also with the feel of songs like ‘Spinning Plates’ which could very well fit in with the likes of Wyatt’s ‘Rock Bottom’. Even during the musical revolutions during punk and post-punk in the late 1970s Wyatt kept his standing at a time when others were getting pushed aside and dismissed as dinosaurs. And don’t forget Wyatt could have easily been included in that group due to his prog-rock associations having been in Soft Machine. But he ended up working with feminist punk band the Raincoats and Scritti Politti during their time with Rough Trade. Some also hold up Wyatt as the “godfather of lo-fi” due his rather primitive playing and simplicity. “That goes back to when I used to like Paul Klee’s drawings: those spidery pen-and-ink drawings with splodgy bits on and rather feeble colouring-in. I used to think that was so great. I remember someone shouting at me once and saying, No, I want a painter who stands up and strides in front of the canvas with big arm strokes and the whole macho thing. And I can see that, but I really like precarious, rickety things and always have done. I mean, I spent quite a few years in very loud bands, making massive amounts of noise, and I enjoyed all that. If you’re opening a concert for Hendrix in front of fifteen thousand Hendrix fans, you can’t piss about. You can’t be whimsical, you’ve got to come up with something. So I do know about all that.” He certainly does.

Band Links:-

https://www.facebook.com/pages/Robert-Wyatt/19289608753https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_Wyatt

Have a Listen:-

Picture Gallery:-

Visitor Comments:- |

| 918 Posted By: Rich, Boca Raton, Fl on 15 Apr 2020 |

|

Is this the Best Robert Wyatt Playlist you have ever seen, I call them MoM's Movies of Music

Robert Wyatt - Catalog Master - Canterbury King

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SuTlA9tU1aE&list=PLUpMRgoYQCduA-r5W3Ko24uMgirleH9Xm

You will find many on my YouTube Channel, including my underground Doc of Kevin Ayers

Channel - RR1234Tube

|

interviews |

|

Interview (2016) |

|

| With the release of a collection of 1960s Canterbury Scene band the Wilde Flowers and associates, founder member Robert Wyatt reflects on those early years, his subsequent musical career, collaborations and political commitment |

soundcloud

reviews |

|

Different Every Time (2014) |

|

| Definitive double CD compilation from eccentric but brilliant English singer-songwriter, Robert Wyatt |

| Comicopera (2007) |

most viewed articles

current edition

Peter Doherty - Blackheath Halls, Blackheath and Palace Halls, Watford, 18/3/2025 and 21/3/2025Armory Show - Interview with Richard Jobson

Liz Mitchell - Interview

Lauren Mayberry - Photoscapes

Deb Googe and Cara Tivey - Interview

Max Bianco and the BlueHearts - Troubadour, London, 29/3/2025

Garfunkel and Garfunkel Jr. - Interview

Maarten Schiethart - Vinyl Stories

Clive Langer - Interview

Sukie Smith - Interview

previous editions

Heavenly - P.U.N.K. Girl EPBoomtown Rats - Ten Songs That Made Me Love....

Trudie Myerscough-Harris - Interview

Doris Brendel - Interview

Beautiful South - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

Dwina Gibb - Interview

Kay Russell - Interview with Kay Russell

Pulp - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

Barrie Barlow - Interview

Sound - Interview with Bi Marshall Part 1

most viewed reviews

current edition

Davey Woodward - Mumbo in the JumboNigel Stonier - Wolf Notes

Wings - Venus and Mars

Kate Daisy Grant and Nick Pynn - Songs For The Trees

Only Child - Holy Ghosts

Neil Campbell - The Turnaround

Philip Jeays - Victoria

Darkness - Dreams On Toast

Suzanne Vega - Flying With Angels

Charles Ellsworth - Cosmic Cannon Fodder

Pennyblackmusic Regular Contributors

Adrian Janes

Amanda J. Window

Andrew Twambley

Anthony Dhanendran

Benjamin Howarth

Cila Warncke

Daniel Cressey

Darren Aston

Dastardly

Dave Goodwin

Denzil Watson

Dominic B. Simpson

Eoghan Lyng

Fiona Hutchings

Harry Sherriff

Helen Tipping

Jamie Rowland

John Clarkson

Julie Cruickshank

Kimberly Bright

Lisa Torem

Maarten Schiethart