Clientele - Interview

by Dominic B. Simpson

published: 29 / 4 / 2010

intro

Dominic Simpson speaks to the critically acclaimed and autumnal-toned the Clientele about their five albums, various EPs and the impact that their native London has had on their work.

The Clientele are one of those special cult bands that invariably seem detached and out of place with everything else around them. At a time when London seems to be spawning any number of garish acts dressed in multicoloured luminescent clothes and over-employing hair gel, the Clientele operate in their own idiosyncratic space, barely affected by any trends and evolving genres around them. Their wistful, bittersweet guitar pop is deeply evocative of London, but not of whatever’s pumping out of the trendy music establishments of East London. Rather, they remind me of the parks in autumn at dusk, with their shadows and fading light; languid, lazy hot summer days slowly giving way to September; hazy, hungover Sundays spent visiting the local markets; half-forgotten memories and ill-defined nostalgia; and the endless "pale exhaust fumes", "laundrettes", "symmetrical terraces", "cracks in the pavement" and "Turkish supermarkets" described so well in the spoken-word track ‘Losing Haringey’, a reference to the North London borough. Yet, just as with the England they often portray, there is a dark side too, encapsulated by lyrics like “and watch the fools go rolling on through still fields as the darkness falls on England green” on the deceptively bucolic ‘We Could Walk Together’. Singer/guitarist Alisdair MacLean will sing it later on in the band’s set, and the lyrics seem prescient at a time of elections, when the nation’s future seems unsure and at a crossroads, while the UK’s public debt spirals out of control, reaching almost the highest in Europe; a continuing recession marked by only weak recovery blighting hopes for the country’s future, while volcanic ash drifts in a dark, menacing amorphic mass over the nation. The first thing I heard by them was ‘The Lost Weekend’ EP in 2001; the opening track, ‘North School Drive’, captured the city perfectly, with it’s lyrics painting a picture in which “the garden sliding past is overwhelming/ Receding through an unreal windowpane/Through watercolour mornings by the newsagents…deliver me to bars and crowds and lights”. But it was also the final track, ‘Last Orders’, that really caught me: an instrumental piano track, solitary and with a beautiful melody, it remains vastly more evocative than many songs dominated by lyrics and a full band playing. The band have been going for nearly fourteen years now, but have their roots stretching as far back as 1990, when they were teenagers at school in the outskirts of London. Twenty years from then, I’m sitting at the Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA) in central London with three of the band’s four members. Buckingham Palace is down the road one way and Trafalgar Square the other; the grandness of the opulent surroundings somehow suits the band’s stately, graceful music (it’s fair to say that Bowling For Soup won’t be playing here any time soon). Later on, they will play a sold-out gig to a backdrop of the 1960’s British TV adaptation of ‘Alice In Wonderland’, Peter Sellers camping it up on screen in black-and-white. The spectral quality of the film brings to my mind the line in ‘Losing Haringey’ about “I was in an underexposed photo of 1982”. Sitting with me shortly after their soundcheck are bassist James Hornsey, drummer Mark Keen, and keyboardist/violinist Melanie Draisey, the latter of whom joined in 2006 and also plays in other acts such as Le Volume Courbe and the Flowers of Hell (and Peter Bjorn and John too, apparently). McClean has elected not to join us; the other three mumble something about “he doesn’t do interviews anymore”. Hornsey wistfully recalls, “It’s nine years since we played [here] at the ICA, supporting Hefner. I remember thinking what a huge venue it is, and now it’s tiny.” I mention their acoustic gig at the Lexington venue in North London recently and Hornsey remembers, “We’ve done a couple of acoustic gigs…it’s very difficult because I play the basslines on an acoustic guitar. I could play on an acoustic bass – I could do, but apparently that’s something Sting would do and I won’t allow it for The Clientele [Laughs]." Wouldn’t you have to fork out for it as well? “No, I’d just borrow one from the Duke of Uke, but don’t tell them that.” The Duke of Uke in question is an increasingly fashionable ukelele and banjo emporium off Brick Lane that both this writer and the Clientele are familiar with, having both practiced there in the studio basement and watched occasional in-store sets on the ground floor while drinking mulled wine with the shop owner. There’s a picture floating around the internet of the band staring pensively out of the shop windows. “Oh yeah, we used to rehearse there,” Hornsey recalls. “We had all our stuff stored there until about six months ago. We kept the neighbours awake playing the piano in there at four in the morning many times.” Did you ever use that huge vintage 1960’s Space Echo keyboard in the corner of the studio? I could never figure out how to get it going… “That’s ours!” Hornsey laughs triumphantly. “Our Space Echo. It’s well worth it. It’s all over ‘The Violet Hour’ and ‘Suburban Light’ [the band’s ‘first’ album, though actually a compilation of Eps]. It’s come in handy over the years.” Those two albums, released near the beginning of the ‘noughties’, capture the band’s early, unique sound: MacLean’s hazy, barely-there spectral whisper sang through a cheap microphone that’s been plugged into a guitar amp, while the band’s sound is woven into gossamer spiralling blanket of reverb. Yet in the following three albums – ‘Strange Geometry’, ‘God Save The Clientele’, and ‘Bonfires on the Heath’ – that reverb-dominated sound has been supplanted by something more defined and pronounced. “Well, we can do that only so many times, I think,” Hornsey contemplates. “Yeah, I think we figured that if we recorded in a bigger studios with a budget and a bit more clarity, then more people might actually want to listen to the records. But they didn’t [laughs]”. Some of the band’s many EPs also captured the band’s self-produced, reverb-heavy early period, where the influence of obvious influences such as Galaxie 500 remained at it’s most obvious. With the band favouring the old-school approaching of including four or five new songs on an EP, do they see EPs as something of a ‘dying art’ in the age of the download? “It’s all a dying art now in the age of the download,” Hornsey ponders. “None of it makes any sense anymore. But we’re going to do another EP very soon – keep it going for a little bit longer. It’s going to have eight songs, so work that one out. It’s going to be a mini-album – well, that’s what we call it in England, but in America and everywhere else that’s an EP still.” They don’t call it a mini-album in America? “No. They don’t know what a mini-album is. We’ve been saying it in every interview in America and everyone’s like, ‘What’s a mini-album’?” Mini-albums are something of a dying art too, of course… “They died about twenty years ago. We’re bringing it back!” The band’s EPs have been consistently brilliant up until the present, and with the likes of the ‘Ariadne’ EP they’ve ventured into uncharted experimental waters: one track, ‘The Sea Inside A Shell’, an eight-minute instrumental collage of keyboard textures, vintage saturated tape sounds and drones, sounded more like something on the drone-rock-friendly Kranky records stable than anything the band would normally attempt on their albums. Along with the aforementioned six-minute piano piece at the end of ‘The Lost Weekend’ EP, this branching out of the band’s ‘normal’ sound is an example of how they can still – despite their relatively conventional sound – be far more daring and original than many other British indie guitar bands, most of whom seem happy to accept mediocrity and complacency. So do the Clientele see EPs as a way of stretching out and exploring their experimental sound? “I guess we do,” Hornsey concedes. “Those EPs that we did were a chance to give us something to do in-between albums really, so we could kind of play around a bit more, and experiment a bit more. Get those things out of our system so they didn’t spoil the albums.” MacLean has mentioned in interviews in the past websites such as UBUWeb.com, which contain a treasure trove of old sound art, modern composers and experimental recordings, some of which doesn’t sound too dissimilar to ‘The Sea Inside A Shell’. “I use UBUWeb a lot, yeah,” says Hornsey. “There’s some great stuff on there. That’s the kind of stuff that me and Alisdair are into quite a lot, so…with that one song [on ‘Ariadne’] we did a very cack-handed version of the stuff we’re into it…I don’t think our drone was particularly good. It was quite rudimentary. We could do a lot better than that…my solo career is going to consist entirely of drones and slap bass [Laughter from band].” So you’ve been to Café Oto [experimental music venue in East London], then? “Yeah,” Hornsey nods, and then, addressing Draisey, ponders, “Maybe you’re gigs [with Le Volume Courbe] have been good there?” “Yeah, they’ve been great,” she recalls. “I love playing there.” MacLean’s lyrics are unambiguously about London, even taking in specific places such as Springfield Park, a stone’s throw from where this writer grew up (and where both MacLean and Draisey lived for a while). Are the lyrics very much just Alisdair on his own? “He writes the main melody, song structure and the lyrics,” Draisey elaborates, “and then he brings it to us and we all add our own bits…we do arrangements, and sometimes things gets changed because of something someone else does.” “We did a lot of arranging on the last album,” Keen pipes up for the first time, his presence almost silent at the table for the majority of the interview. “Personally, when I was thinking of the arrangements, I wasn’t necessarily listening to the words to get an atmosphere at all. So yeah, the words didn’t really have any influence on what I was doing. It was just purely musical.” Draisey agrees: “Yeah, it’s different with arrangements and when you’re writing songs from the start…it’s not something that we’d ever really think of doing because it’s something that Alisdair just does.” The music is everyone though, I guess? Draisey: “Yeah, completely.” Keen: “The songs will take on a personality soon after Alisdair comes out with a song…it’s a case of listening to the…” The rest of his sentence is drowned out by Hornsey returning with pints of beer from the lofty ICA bar, while more and more people are trickling into the venue. “Alisdair writes them and then he comes to us and we approve them,” Draisey adds after a pause. “One by one. I send him back the lyrics with a mark out of ten on the back”, Hornsey interjects to guffaws. Then more seriously: “On the new album, Alisdair wrote the songs, and then he kind of recorded his parts and just gave us free reign to do whatever we wanted on them – so they’re very much…” – he pauses to find the right words. “The lyrics are his lyrics but the songs are very much our songs – the way it sounds…everyone here worked really hard on the arrangements.” “He just totally gave us free range,” Draisey nods. MacLean has often spoke of his lyrical influence in interviews, which range from classic British children’s fantasy novel ‘The Dark is Rising’ by Susan Cooper to so-called ‘pop-art’ or ‘cut-up’ lyrics and the Situationist writers. Something of the latter is reflected in the cover of ‘Bonfires on the Heath’, originally by the 16th century Italian artist Giuseppe Arcimboldo, whose paintings specialised in portraits of noblemen’s faces that actually turn out on closer inspection to be made up of fruits, vegetables, flowers, fish, animals, books and Lord knows what else. Look closely at the person’s face on the album front cover and you will see flowers, berries and (perhaps less romantically) what looks like a turnip in the person’s forehead. Hornsey admits to have never read ‘The Dark is Rising’ and shrugs, “Alisdair has always expressed a bit of a pop-art direction, but you’d have to talk to him about that”. But he is animated when discussing the Situationist movement: “Well, Alisdair and me we were really into our surrealist stuff when we were growing up… yeah, he [Arcimboldo] was great. 16th-century, so not really a surrealist as such, but a big influence on a lot of them, I think…we’re more into surrealist literature than art, so more poetry and stuff…” What kind of writing? “Louis Aragon, André Breton, Robert Desnos…I could go on for hours. You don’t want me to go down that road! And we’re quite lucky because we discovered Atlas Press and Exact Change Press when we were younger – they published so much great stuff...so I just kind of buried myself in the English or French department of the library of my University, and just worked my way through all that stuff…” Exact Change Press is in fact the publishing imprint run by Damon and Naomi (formerly of Galaxie 500), with whom Hornsey and MacLean will play onstage with a few weeks from now. Hornsey and MacLean met at school, where they bonded over a love of Felt, Galaxie 500, Love, the Zombies, Television, the Chills, and The Incredible String Band; they would draw the band names on their pencil cases. Hornsey recalls: “Alisdair was always kind of listening to the West Coast psychedelic stuff in the 60s, and I was listening to all the 80s inheritors to the sound – the Chills, Galaxie 500, Felt – and then we kind of crossed over and made each other tapes and stuff…” I only discovered The Chills’ classic ‘Pink Frost’ recently. “Oh man, I’d love to discover that track again”, Hornsey exclaims wide-eyed, before adding in a deadpan tone: “It’s the greatest song of all time.” Early incarnations of the band featured Billy Mahonie drummer Howard Monk (now a gig promoter), who was replaced by Keen (“Billy Mahonie got really famous and he decided to quit the Clientele to pursue post-rock”, is how Hornsey puts it, but adds: “They [BM] do get together every now and again. And they sounded absolutely fantastic when they played recently”). Another former member was guitarist/vocalist Innes Phillips, who went on to form the Relic and once played with Hornsey at the legendary Spitz venue, this website’s former live home and still very much missed after it closed down. The Spitz was something of a home to the Clientele too: “We played about three or four shows there,” Hornsey recalls affectionately. “Was I there?” Melanie asks. “No, your first gig with us was at the Bloomsbury Bowling Alleys…” People do karaoke there in soundproof rooms so you can see them doing ‘Sweet Child o’ Mine’ in silence. Hornsey: “That was actually in the set-list for us that night [laughs]”. Keen recalls: “We were getting a massive cheer after every song when we played at the Bowling Alleys, and then we realised it was the people in the karaoke booths.” Going back to early days of the band, Hornsey explains: “The Relic was the Clientele plus Innes Phillips. He [Phillips] was in the Clientele. But basically he left The Clientele…” Was there any particular reason? Drug bust-ups? “Apart from the drug bust-ups…” Hornsey jokes, ”his songs and ours when we first started were very much incompatible in one band – they kind of went in their own directions. So it made more sense to do two bands, which we did. It almost worked wonderfully in a kind of Go Betweens-way with the two of them, but it was too much for a one band…so we created two bands and then he moved to Australia after the first album.” Can you hear the music of the afore-mentioned acts seeping into the Clientele’s music? Sometimes – as with Galaxie 500’s languid cover of the Velvet Underground’s ‘Here She Comes Now’ – there’s an undoubted similarity… “I don’t think we have any direct influence, but we’re just operating in the same area, really,” Hornsey considers. “We have the same influences as they have.” What about other influences such as jazz or the Chicago school of post-rock? I’m thinking of the fact that Alisdair also has a side-project called Amor de Dios [“Love of God” in Spanish]… “Yeah, with his girlfriend Lupe – they’ve got an album coming out soon. I think they’d describe themselves as Tropicalia rather than jazz. But there’s a jazz influence on all of the Tropicalia stuff – Os Mutantes and all the rest…[but] I’ve not heard any of it [Amor de Dios], so…you’ll have to check them out, I dunno,” he ponders. “We all listen to a lot of jazz. Mark listens to shitloads of jazz. I like a lot of screechy nasty 60s jazz – Pharoah Sanders, Sun Ra…” I remember Alisdair saying that he likes some American post-rock too that goes off into jazzy directions – Tortoise offshoots like the Sea and Cake and The For Carnation… “The Sea And Cake, yeah. Not sure if they’re an offshoot, but they share a drummer. John McEntire is the connecting point in most of them because he produces and plays drums with most of them. We were very lucky – we went out with Archie Prewitt [from Tthe Sea and Cake] in Chicago and played with him many years ago in New York…we were listening to Slint a lot when we were sixteen.“ One tenuous link that can be consider about all the acts cited above is that none of them are British. And indeed, the Clientele paradoxically have always been in the curious position of being slightly more well-received abroad than at home, despite having – what seems to me, at least – a very recognisably British sound. Do you have any idea why the British press have ignored you so much while American music websites such as 'Pitchfork' have lavished praise? Hornsey: “We were in 'The Sun', 'The Daily Mail' and 'The Daily Express' [laughter]. They’ve ignored us for ten years, but now they like us – suddenly we can sell out the ICA whereas before we’d be playing for ten people at the Luminaire. So I don’t know what’s happening, but something’s happening…maybe they left us alone for so long, that now there’s a really good story they can tell – ‘Look us at this band doing really well in America, but no-one knows who they are over here. How weird’…I mean, we get great crowds in the US wherever we go. To be honest…over here, if we play outside London, we get no crowds. Glasgow does alright for us, but other than that…we’re playing Liverpool soon, though. I’ll get very emotional. I’ll probably start crying, as I lived there for many years [at University]…” The praise abroad isn’t just confined to America. Some of the Clientele’s Eps came out on Spanish labels such as Acuarela and Elefant. As Hornsey says simply, “We love going to Spain. And they love selling our EPs. So it’s very mutually beneficial.” Who got in touch with whom first? “Elefant were one of the first people to get in touch with us and then we met Acuarela and we’ve been working with him ever since. They still take us out there to all these festivals – we’ve been asked to play Benecassim…” And Primavera? “Yep, again through Acuarela. They’re really good for getting us these gigs… Primavera is just like, every venue in Barcelona is taken over by the festival”. So it’s not like Reading? “I don’t think so, no. It’s just different venues…I think they have a festival stage somewhere as well, but all of where we’ve played have been in venues…” So less annoying Frisbee players and old hippies walking round with corn in their hair? “Exactly. Not having any of that.” Have you played the Green Man festival (where this writer went recently and endured rain for three days)? “No, we haven’t. We don’t get to play English festivals,” he replies curtly. I’m not sure if his tone is one of frustration of the fact, or relief. Moving on, does Melanie ever get double-booked, what with all the different bands she’s in? “I’ll answer that,” Hornsey says in a deadpan authoritive Chairman-like voice. ”The Clientele take priority in all of Mel’s negotiations [laughs]. It’s clear to her now.” “I did have them clash one year, when I was playing violin with Primal Scream,” Draisey reveals. “And they [The Clientele] were recording a song for 'Yo Gabba Gabba,' which I really wanted to do – but I’d already said yes to a Primal Scream gig.” Is 'Yo Gabba Gabba' something to do with the Ramones? “It’s an American children’s programme – it’s fantastic,” Hornsey enthuses, correcting me. “They do a little animated thing every episode. It’s just a TV program where they do a little song – they write the song and they get bands to play them.” The Clientele’s song was called ‘Come & Play’, which Draisey proceeds to sing. Is it like 'Sesame Street'? “No, it’s more like 'Teletubbies'” Hornsey says, “and it’s probably the best TV programme in America. And our song is the best Clientele song. And Mel wasn’t on it, because she went to do something else”. In the style of every other band now, Primal Scream are going to be playing ‘Screamadelica’ track-by-track soon… “God help us all. Though Brian O’Shaughnessy who produced our records did that,” Hornsey considers. With regards to producing, do you generally have the same producers on your albums, or do you try a new producer each time? “The first few albums we did by ourselves; then we got Brian on board for ‘Strange Geometry’; and then we went to Nashville [for ‘God Save The Clientele’] and then came running back to Brian for the last one [‘Bonfires on the Heath’]…” So who produced ‘God Save…’? “That was Mark Nevers,” Hornsey remembers. “Brian kind of rescued it in London afterwards, and then the latest one was Brian again. He’s done a really good job with us, Brian…” What was the reason why you did the new album back in London… “Cheap,” interjects Hornsey laughing, reading my thoughts. “That’s not the reason, it’s because we wanted to work with Brian again. And he was in London. And then we could take extreme complete control of the project, whereas being in America [for ‘God Save…’] we weren’t because we couldn’t stay out there for mixing. It was out of our hands….” Do you ever get fed up with touring, and the fact that you are playing the same songs every night while not being able to come up with any new ones? This has been pointed out by a number of other bands in the past in reference to the downside of seeing all those fascinating new cities around the world from the inside of the tour bus… “I’m sure Alisdair does, probably,” Hornsey considers. “We don’t really learn anything new on tour”. “Sometimes Alisdair writes stuff on tour,” Keen points out. “If you’ve got one of those schedules when you’ve got time…," Draisey ponders. “Alisdair wrote a couple of great songs from ‘God Save The Clientele’,” Hornsey remembers, “while we were on tour a couple of years back, and then we recorded them straight after touring Nashville. And then one of my favourite songs on the album was recorded on the tour – ‘These Days Nothing But Sunshine’.” Draisey complains that she’s feeling ill and that her voice is in a bad state – which she’ll repeat onstage – and the interview is drawing to a close. While we’re talking about the band’s forthcoming plans – the eight-track mini album mentioned earlier, a West Coast tour of the USA around September - Hornsey watches me keenly and then touches on a rumour: “You didn’t ask us why we’re splitting up, which is kind of fascinating – but let’s not go down that route…” “The answer to that question is that every band splits up in the end…it’s just a matter of time…,” Draisey adds, philosophically. It’s a case of que sera sera… “Exactly.” “I don’t see the point in splitting up anymore, though,” Hornsey contemplates, “because you’re only going to get back together next year anyway”. You’re probably going to do one of those All Tomorrows Parties reformations in ten years time… “I really don’t want us to end up like the band who reforms and then does a show playing their old albums again, like every other fucking band in the world who’se split up…” “You have to play a couple of the old songs, though…,” Draisey interjects. “I don’t mind playing old songs – we always play old songs, but I wouldn’t want to reform just for that purpose”, Hornsey counters. “What about ‘The Violet Hour’?” Draisey asks. “Oh, I’d do that one”. That’s a great album, especially that song ‘Missing’. A Mexican couple used that song at a wedding. “That’s my favourite Clientele song!” Hornsey agrees. “We met a couple in Ann Arbor who had their wedding dance to a Clientele song.” What was the song they were dancing to? “’Saturday’ on ‘Suburban Light’.” I have to get Hornsey to repeat the name of the song twice because, as he admits himself, “I can’t speak properly because I haven’t eaten anything all day and I’ve had about three hours sleep – I was out boozing last night with a friend…” He scratches his days-old stubble and ponders the fact that he will be onstage soon having barely shut his eyes in the last twenty-four hours. And with that he’s off, Keen and Draisey following him, as they wander around the ICA’s plush interior, cracking jokes with the PR people milling around. Later on, they fill the ICA gig venue with light and beauty, leaving a sold-out audience spellbound, and climaxing with ‘House On Fire’, which has been requested all night from the crowd. When they exit the stage, it’s timed perfectly with the ending of the film behind them, the transparent, ghost-like faces of Peter Sellers and Peter Cook imprinted on the audiences mind as the credits role. The photographs that accompany this article were taken for Pennyblackmusic by Matt Williams.

Band Links:-

http://www.theclientele.co.uk/https://www.facebook.com/theclienteleofficial

https://twitter.com/theclientele

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Clientele

Picture Gallery:-

interviews |

|

Interview (2015) |

|

| Tommy Gunnarsson speaks to Alasdair MacLean, the front man with cult indie pop band the Clientele, about their new compilation,out a compilation called 'Alone and Unreal: The Best of the Clientele', and their past, present and future |

| Interview (2002) |

live reviews |

|

Uffe's Kallare, Växjö, Sweden, 16/10/2002 |

|

| The Clientele recently played a four date tour of Sweden. Tommy Gunnarsson catches them on fine form and at their intimate best in a tiny basement club |

reviews |

|

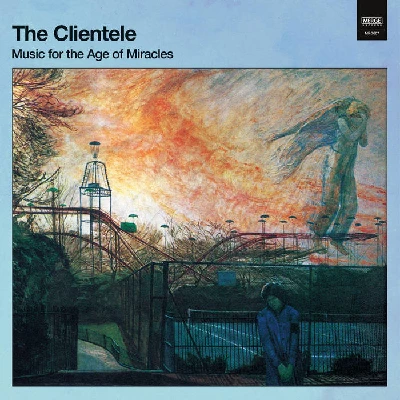

Music for The Age of Miracles (2017) |

|

| Fabulous, long-awaited album from melancholic indiepop outfit the Clientele who have returned after a seven year absence this time with a new fourth member |

| Alone and Unreal: The Best of the Clientele (2015) |

| Minotaur (2010) |

| Bonfires on the Heath (2009) |

| Lacewings / Policeman Getting Lost (2004) |

| Lost Weekend (2002) |

| Suburban Light (2001) |

most viewed articles

current edition

Carl Ewens - David Bowie 1964 to 1982 On Track: Every Album, Every SongBillie Eilish - O2 Arena, London, 10/7/2025

Bathers - Photoscapes 2

Bathers - Photoscapes 1

Cleo Laine - 1927-2025

Hothouse Flowers - Photoscapes

John McKay - Interview

Editorial - July 2025

Simian Life - Interview

the black watch - Interview

previous editions

Heavenly - P.U.N.K. Girl EPTrudie Myerscough-Harris - Interview

Pixies - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

Boomtown Rats - Ten Songs That Made Me Love....

Fall - Hex Enduction Hour

Peter Paul and Mary - Interview with Peter Yarrow

Sam Brown - Interview Part 2

And Also The Trees - Eventim Apollo, London, 21/12/2014.

Doris Brendel - Interview

Place to Bury Strangers - Interview

most viewed reviews

current edition

Sick Man of Europe - The Sick Man of EuropeAmy Macdonald - Is This What You've Been Waiting For?

Phew, Erika Kobayashi,, Dieter Moebius - Radium Girls

Alice Cooper - The Revenge of Alice Cooper

Blueboy - 2

Lucy Spraggan - Other Sides of the Moon

Cynthia Erivo - I Forgive You

Bush - I Beat Loneliness

Davey Woodward - Mumbo in the Jumbo

Philip Jeays - Victoria

Pennyblackmusic Regular Contributors

Adrian Janes

Amanda J. Window

Andrew Twambley

Anthony Dhanendran

Benjamin Howarth

Cila Warncke

Daniel Cressey

Darren Aston

Dastardly

Dave Goodwin

Denzil Watson

Dominic B. Simpson

Eoghan Lyng

Fiona Hutchings

Harry Sherriff

Helen Tipping

Jamie Rowland

John Clarkson

Julie Cruickshank

Kimberly Bright

Lisa Torem

Maarten Schiethart