Walkabouts - Interview

by John Clarkson

published: 18 / 7 / 2003

intro

Seattle's much acclaimed the Walkabouts first formed in 1983, and since then have released 13 albums. Frontman Chris Eckman chats to John Clarkson about his band's long history, and the band's 20 years together

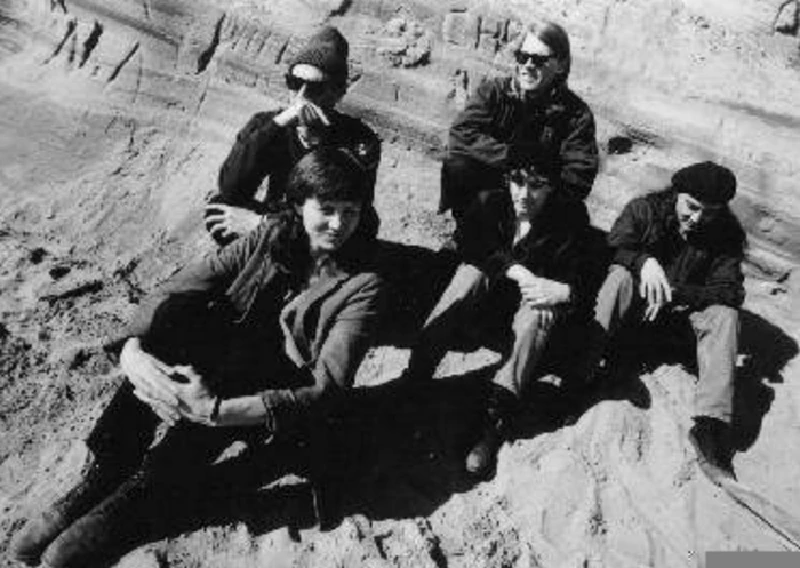

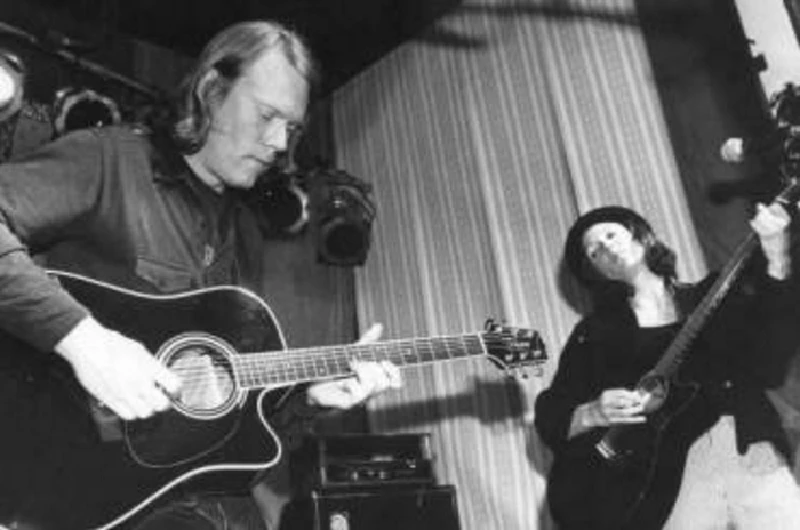

The Walkabouts come from Seattle, and were formed by Chris Eckman, a philosophy student (Vocals, Guitar), and the classically-trained Carla Torgerson (Vocals, Guitar) in 1983 when they met while working at summer jobs in an Alaskan fish cannery. The Walkabouts, which in their earliest line-up also featured Eckman’s two younger brothers Grant (Drums, Percussion) and Curt (Guitar), released their mini debut album, ‘22 Disasters’ on their own Necessity Records in 1984. Their second album , ‘See Beautiful Rattlesnake Gardens’, followed on another small Seattle label, Pop Llama Records, in 1988. For their third album, ‘Cataract’, which came out in 1989, the Walkabouts switched labels again, this time to the larger Sub Pop. The Walkabouts at this stage were principally a folk act. As both the Seattle music scene and Sub Pop, which at that time also had Mudhoney, Soundgarden and the young Nirvana on its books, began to develop an increasing international profile, they found themselves, often to their disbenefit, associated with the then emerging grunge movement. They would remain at Sub Pop for their next two albums, ‘Rag and Bone (1990) and ‘Scavenger’ (1991). Always more popular in Europe where they became immediately successful after a first tour there in 1990, they then shifted camp again, this time to Sub Pop’s European offshoot, Sub Pop Europe/Glitterhouse, where they would stay for their next three albums, ‘New West Motel’ (1993), ‘Satisfied Mind’ (1993) and ‘Setting the World on Fire’ (1994). The last of these albums, which had a rock sound, attracted the interest of Virgin Records, with whom the Walkabouts recorded their ninth and tenth albums, ‘Devil’s Road’ (1996) and ‘Nighttown’ (1997). The first of these albums found the band working with the Warsaw Philharmonic Orchestra, while on the latter they appeared with their own Nighttown Orchestra. While the Walkabouts had signed with Virgin Records to make three albums, they left after just these two, and then returned to Glitterhouse, with whom they have since released another three albums, ‘Trail of Stars’ (1999), ‘Train Leaves at Eight’ (2000) and ‘Ended Up a Stranger’ (2001). The Walkabouts’ constant link has always been Eckman and Torgerson, and the band has been through several line-up changes. Since 1989, the group, however, has also featured keyboardist Glenn Slater, and since 1993 drummer and percussionist Terri Moeller. The role of bassist has been over the last years what Eckman has described as “a revolving door”, but the group has been recently rejoined by Michael Wells, who was also the bass player in the band between 1985 and 1996. Like any other long-serving group, the Walkabouts have gone through many difficult periods, but perhaps none worse than when John “Baker” Saunders, the group’s bassist between 1996 and 1999, who had left the band a few months beforehand, died of an accidental heroin overdose 10 days before they were due to begin recording the ‘Trail of Stars’ album. As well as their own songs, the Walkabouts have also garnished a reputation for recording strong cover versions of other people’s songs. Their 1993 album ,‘Satisfied Mind’, featured covers of numbers by artists such as Patti Smith, Nick Cave and John Cale, while their 2000 record 'Train Leaves at Eight’, which has a European slant, has covers of songs by Serge Gainsbourg and Jacques Brel, and also several more obscure acts from Greece, Slovenia and Finland. The group’s latest project is ‘Slow Days with Nina’, a five-track mini-album tribute to Nina Simone, which, two years in the making, was completed a month before the jazz chanteuse’s untimely death and has just been released on the small British label, Shingle Street. The band also released a compilation, ‘Watermarks’, for the American market on the Innerstate label at the end of 2002, and has another as-yet-untitled “best of” compilation coming out on Glitterhouse later this year. In a candid and frank interview, Pennyblackmusic spoke to Chris Eckman about the Walkabouts’ 20 years together. PB : Can we start right back at the beginning? In the early 80’s, before you began playing in the Walkabouts, you were in a punk band, the Innocents. Who were they ? CE : We were a 50% cover band. We did the Clash and the Buzzcocks and the Jam and the Only Ones, but we also tried to write our own songs. I was at university at the time .It was a fun thing really. I put no serious weight behind it when I was actually doing it, but it got me closer to music, and it was, therefore, a big first step. I don’t want to denigrate the music itself. We weren’t a very good example of it though. That kind of music was an incredible influence on me. When you’re 16 or 17, and you have an interest in just somehow rawly expressing yourself, that sort of music can be incredibly inspiring. It’s almost a cliche now, but there really was this attitude at the time that almost anyone could pick up a guitar and write a song and make some noise on a stage. It offered a lot of hope in a way. PB : You then met Carla Torgerson working in an Alaskan fish farm during your university summer holidays. That was in 1983. How long after that did you form the band ? CE : We actually officially formed the band within about five minutes of meeting. She had been travelling and studying abroad in Europe for some years. I wasn't aware of her beforehand, but she had actually started going to the same university as me. Within about the first five minutes of us talking she said “I want to be in your band", and so we started to play that summer. It was really boring where we were, and it was extremely isolated, and so that was more or less when the partnership was formed. PB : Her musical background is very different to yours. It is largely classical, isn’t it ? CE : She was a trained classical musician in the cello, and also had had piano lessons. She had been folk singing since she had been big enough to hold a guitar. Her whole family was incredibly musical. They had always gone to the symphony and the opera. It was the complete antithesis of my upbringing where my father owned I think four records, and never played them (Laughs !). My brothers and I never had music lessons. It was the total opposite really. PB : The first Walkabouts record, ‘22 Disasters’, was a five track mini album, and came out in 1984. There was then a long gap until your first proper album, ‘See Beautiful Rattlesnakes’, which came out in 1988. Why was there such a delay ? CE : We actually recorded a follow-up album between those records. We financed it ourselves for a ridiculous amount of money for a band that was still playing clubs at the time. We sent it out to a few labels and really very quickly a label in Canada called Wrestler Records called us back and said “We’ll put this out”. We waited six months, nine months, a year, but the record never came out. By that time we really weren’t very interested in the songs anymore, and the band really was within a small step from breaking up. ‘See Beautiful Rattlesnakes Gardens’ was more than anything an attempt to document our live show at the time. We were basically going to pass out cassettes to people and say “Thanks. It was really fun doing this. Now, let’s get on with our lives.” We started to do this, and I remember recorded 16 or 17 songs over a long weekend, and didn’t much think about it. I was thinking about going back to graduate school at the time, and then the guy, who engineered it, called me up about a month later and said “You should really go back and listen to some of this stuff. It’s not bad”. Then a local record company guy heard it and was interested and the whole thing more or less just started up again (Laughs). It was a strange four years between ‘22 Disasters’ and ‘See Beautiful Rattlesnakes Gardens’. We were highly motivated, but then started to lose our way , and to think that maybe music wasn't the best choice for our lives.Then after the album proper came out, things started up with a vengeance again. PB : By 1989 you had signed to Sub Pop. You were one of the few Seattle bands at that time on that label, which wasn't a grunge act. Why do you think they signed you ? CE : Well, you have to attempt to visualise how small Seattle really is. It was actually at that point a city of less than 500, 000 people, and it was never a musical centre for America at all. It was really the backwater, so the scene itself was really small. There was more or less 200 or 300 people who were the hardcore scene, and these 200 or 300 people more or less spread themselves across all the club shows. They would go to see Soundgarden. They would go and see the Walkabouts. A differentation wasn’t really made. There was like this pre-grunge movement. It was pre-grunge, before the term was coined. Sub Pop was founded by two local guys. They weren’t actually from Seattle, but they had lived there for quite a long time, and were both involved with different parts of the music industry. Bruce Pavitt was a journalist, and Jonathan Ponman was a local DJ at the college radio station and also booked shows from time to time, so these were guys we knew. They were guys we saw in the clubs. By that time we had gone ahead and recorded 'Cataract' ourselves, but this time much more intelligently, more or less in the after hours in studio time. My brother, Grant, who was the drummer at the time, worked with Bruce in the same company in a job just making ends meet. He handed Bruce a tape of it, and then the next day Bruce came to work and said “Hey, we’ll put it out. What the heck !” Sub Pop didn’t really have a fully formed vision at that point. I think they saw themselves as being something like Sun Records, and were simply concerned with chronicling their local scene, whatever that scene was, and whatever manifestations it took. At that point in time we were one of the bands bringing people into the clubs, and so from a local perspective it made perfect sense for them to hitch up with us. It all got very strange in the years to follow. They became defined, not only by themselves, but even more by the media and the start of grunge, and here we were the winsome, folky Walkabouts standing off to the side (Laughs). PB : The group’s always been more successful in Europe. For the last few albums you have not had an American deal. CE : Actually for the last few we have. We had no American deal from about 1993 to almost 2000, but ‘Ended Up a Stranger’ came out domestically. We also released 'Watermarks', a Greatest Hits things domestically. We do now have something of a presence in the United States, after a long protracted time where we had nothing. PB : At what stage did you start hitting it off in Europe ? CE : That was down largely to Sub Pop. By the time our turn came around to be considered for a European tour most of the other bands had already gone. We went there for the first time in 1990. Frankly things weren’t going amazingly well at that stage in the States. We had done three national tours, and it was really up and down, sometimes fairly decent, but often not so good. We had very good press support everywhere, but that doesn’t necessarily bring people out, especially in America. We were fish out of water. We played places like Chicago, and there would be twenty guys with their baseball caps turned around in the front row expecting Tad, and we would start out with some acoustic song with Carla playing the cello (Laughs). It would all go amiss very quickly. It became almost like a perverse ritual for us. The more these sorts of people would pack into the front rows the less we would rock . It had the opposite effect, because by that stage we had become tired of being labelled with the whole grunge thing. We more or less begged to go to Europe, but not because though we thought that there would be any great demand for us. We had done two albums and an EP, and figured, that as things weren’t going very well overall, what the hell did we have to lose ? Maybe we would just break up afterwards. The band was in a perpetual state of breaking up. Things were quite different on that 1990 tour though. It was not a barnstorming thing where we played sold out places everywhere, but there seemed to be more interest in what we were doing. A few nights were really good. From that point onwards we thought that we should really open up to include Europe and certainly by the time we did ‘Scavenger’ it was a whole different story. PB : You probably get asked this question all the time, but why do you think you have been such a success over here ? CE : I think that it is a combination of things. I think that the more philosphical or theoral theories would run that there is something in the European psyche which reflects upon what we do or are more open to it. I tend to resist that one though. I think that a lot of it was enthusiasm by the record company , which was Sub Pop Europe who evolved into Glitterhouse, at the early stages. Those guys seemed to be really clued about what we were doing, and it really transcended just down to that. They seemed to be really interested in us. I am not saying that Jonathan and Bruce and Sub Pop America had given up on us, but they had become overwhelmingly swamped by the grunge thing. In a way they didn’t really have to work those records. Those records worked themselves. I am not saying that they didn’t do a lot. They were busy all the time, but when people are calling you up and demanding stuff time after time you tend to go in that direction. With the Walkabouts you had to prod. You had to find a hole to fit us in. We were more of a thing that you had to kind of work on. For whatever reason the Sub Pop Europe people seemed to have the time to do that, and it just worked a lot better. PB : By 1996 you had signed to Virgin Records. One of the highlights of the Walkabouts’ career has been the ‘Devil’s Road’ album, which came out later that year and which found you moving into a more symphonic sound and working on some of the tracks with the Warsaw Philharmonic Orchestra How did you become involved with the Warsaw Philharmonic? CE : A lot of that was really down to chance. We were hungry to do something different. A lot of our even longer term fans said to us at the time "Ah, those strings. You’re doing them because Virgin is making you do them”. It was really quite the opposite though. Virgin signed the band that did the 1994 ‘Setting the Woods on Fire’ album , which was by far the most rocking record we ever made, and is still to this day. They came to our shows at about that time. They were highly enthusiastic about what we were doing, but we had moved on and decided that we didn't want to do that anymore and it was no longer what we were interested in. We have always loved stuff like Nick Drake, Love, and John Cale, things-for want of a better word-that have an orchestral pop sound. We had the means to do it, after we signed to them, and so we started recording. We got this guy Victor Van Vugt to produce it. We knew that he had worked on Nick Cave’s ‘The Good Son’, which had a lot of strings on it, and would be sympathetic. There really was no one in Seattle at that time who would have understand what we wanted to do with that record, and so we had to look outside. We ended up in the Conny Plank studio in Berlin, which is a wonderful place where a lot of the Krautrock stuff had been done in the 70’s, and also was where the second album by the Tindersticks, who we also got to know around that time, was recorded. Interestingly enough, the Tindersticks wanted us to tour with them in England and also on the continent because they loved the ‘Satisfied Mind’ album, which ironically went in a whole other direction from the orchestral thing, As they were already working with strings, they were able to give us a lot of accurate information. We really bled them for everything we could get out of them (Laughs !) as regards how to make our turn into orchestration. We got in touch with the Warsaw Philharmonic Orchestra after we started recording in Germany. We began to think about where we could afford to work, and we decided that the East would be significantly cheaper than if we decided to do it say in London. That’s really how we ended up in Warsaw, but it was a brilliant move. We got on the train and went there and they were fabulous players. We played in an old radio studio. It was really fantastic. PB : Your next album was ‘Nighttown’ which found you working with your own Nighttown Orchestra. Who were they ? CE : The Nighttown Orchestra were a variety of people. We called them that, but they were more or less two different bunches of people, and there was a Nightown Orchestra US and a Nightown Orchestra UK. The US version were all Seattle-based people, and they were the the ones who appeared on the album. We did a short tour in Europe that lasted for about ten days with an orchestra, and the UK version were the people who went with us on that tour. All those people came from London mainly, and were people we hooked up with through the Tindersticks. PB : By the end of the decade you had left Virgin, despite selling quite a lot of copies of ‘Devil’s Road’ in particular. Why did they decide to let you go, and were you pleased to leave ? CE : I have to say we were pleased to go. We were so pleased to go that we actually asked to leave (Laughs). We would have definitely been dropped though, because at some point I would have just given up making demos. They asked us to make demos for a third record with them. We went into the studio and did some stuff that I thought was really pushing the boundaries of what was interesting to us, because they had been begging and asking us-rather politely I have to say-for some sort of devil’s package. “Just write us one rock song, and then you can do whatever the Hell you want on the rest of the album.” For about 15 minutes I entertained the idea. I guess my attempts weren't very cerebral though (Laughs), and so it became clear that the relationship was going to go. ‘Devil’s Road’ was, as you say, extremely profitable, but we really believed that ‘Nighttown’ was the better album. It was more where we wanted to take our music, but it would be no exaggeration to say that Virgin hated it. One guy was even quoted, as saying, “that this is the sound of a band committing suicide”. That remains one of my favourite industry quotes of all time (Laughs). Many of the hardcore fans consider it to be one of the best. I did too at the time. I was just in love with that record, but we met with nothing but disappointment with it. We handed it to them, and they did nothing. They revoked our advertising budget. They never made a single. We had ridiculous success with the song ‘The Light Will Stay On’ on ‘Devil’s Road’,especially in Germany, but on this follow-up record, barely a year later, they didn’t even produce a single. Whatever major label album has been put out that didn’t even have a single ? They just ran away from it like it was Lou Reed's ‘Metal Machine Music’. It was just crazy. PB : How much of that do you think was because Virgin was largely pushing very manufactured products like the Spice Girls at the time ? CE : It was definitely down to that. In the mid 90's, the industry started to change enormously. Now we look back on it and see those days as the good old days. That was 1997 and since then things have got much worse. They're really horrible now. That was just the beginning of that. We actually signed to Virgin Germany, and the guy who was the president of that company then is still there. He’s actually quite a reasonable guy. When we signed, he told us “This is a three album strategy. We’ll do three records and then we’ll see where we’re at.” He was quoted a couple of years ago in some German music press thing as saying “we no longer do artist development”. Those days are really done. They look at things, and they have to sell between 300,000 to 500,000 copies before they move on. Anything that falls short of that they just run away from. PB : You returned to Sub Pop Europe/Glitterhouse for your next album, 'Trail of Stars'. Why did you decide to go back there ? CE : Well, it was something that we always knew that we were going to eventually do to be honest. I didn’t ever think that we were going to have some sort of glorious 15 year career with Virgin Records. At the time we decided to sign with Virgin in 1995 Sub Pop had actually signed with Warner, so at that point Sub Pop was basically dissolved. Glitterhouse was suddenly just Glitterhouse. Glitterhouse hadn’t really released Glitterhouse records for 7 years. They were really small at that point. They advised us "we're not going to have the means of distribution to release your records at the level you want", so it was quite amiable that we left, but there was always this sort of nudge,nudge agreement. "You’re going to grow in these few years that we are gone, and then we’re basically going to come back up." It really was something as simple as saying that one day we were going to leave Virgin, and the next we were going to be recalled to Glitterhouse, and that’s basically what happened. PB : That album that followed, ‘Trail of Stars’, was recorded at an incredibly bad time for the band. Terri Moeller left for a while afterwards. You had a former bassist, John "Baker" Saunders, who died, and for a while it looked like you might break up. Why do you think you stayed together ? CE : There are a lot of reasons why we stayed together. Once we left Virgin the chances of us keeping things going as a collective career more or less evaporated. We were no longer at a stage where the Walkabouts could pay six or seven people’s salaries, and keep them all alive full-time, so we really did have to consider what was going to happen. There were a number of enormous things happening at that time. Carla and I had been together for many years. We had just split up. We had left Virgin. Baker had died. He had actually left the band some months before, but died 10 days before we went into the studio to do ‘Trail of Stars.’ The whole thing was too much. I think that in some ways we have always held music in our minds as something rather like a heart. It is something which means more to us than just how you make money and how you get by as a career or anything like that. I think that through those really low times that has been more or less what has always got us through. People have very different opinions about that record. A lot of people think that it is our worst record, but I know other people who think it is our best.It was probably a foolish time to make a record, but that record sounds more like I wanted it to sound than any other record. Whether that sounds good to people I don’t know (Laughs), but I really feel like that there was so much awfulness going on when we made that album that we really made a record that had a lot of the feelings and emotions for better or worse from that period. A lot of people find that record highly depressing. It has an extremely claustrophobic sound, but a lot of that was very deliberate. We were really trying to strip things back on that record. PB : It’s in complete contrast to ‘Devil’s Road’ or 'Nighttown’, both of which were more expansive. CE : It’s doesn't have that widescreen thing. The only way we could see making an album at that point was that way. There was noone we really wanted to invite into the crazy situation that we were in at the time. There was really no room for anyone else, so that was the record we ended up with. PB : You got through that though, and you then recorded another remarkable record, the covers album ‘Train Leaves at Eight'. You had done another covers album, ‘Satisfied Mind’, before which focused mainly on American artists. This one, however, was more European in feel. The tracks were often by really obscure artists from places like Slovenia and Finland. How did you come across these songs ? Was it just on the road ? CE : A lot of it was. Yeah ! Over the years one of the nice side effects of having been in the band is that people just hand you things.I think that we realised after a while that we had an enormous resource of music available. I also knew from travelling especially on the continent, and having lived on the continent-I lived in Portugal for a few years before living in Slovenia- that a lot of people, even over a simple border, didn’t know what was going on in other countries. We’re not so special, but the one thing about us is that we cross these borders all the time. As we are not a part of any one of these specific cultural milieus, as we’re in a way on the outside, we don’t have so many cultural preconceptions about what kind of music is this and what kind of music is that. We respond to it more on a gut level instinct. PB : You’re now about to release an album of Nina Simone covers, 'Slow Days with Nina'. Why did you decide to record these ? CE : You know I don’t know why we end up doing half the things we do (Laughs). ‘Train Leaves at Eight’ was one of those things that was discussed in the back of a taxi somewhere in Europe, and nine months later we were in a studio paying studio bills to do this crazy idea, and wondering how the fuck we could pull it off. That record was just an enormous amount of work, translating songs and trying to figure out how to adapt our sound to what was often ethnic folk music. It was really crazy, and the Nina Simone thing again was one of those five minute decisions. We got approached by a very small label in England called Shingle Street. It’s only done four or five albums before, and the owner said “I know you are signed to Glitterhouse, but I would really love to give you the opportunity to do something on the outside of what you normally do. Just come up with some crazy, outside idea and we’’ll do it as a mini LP and I’ll release it.” Both Carla and I are huge Nina Simone fans, and Carla especially. This is something that she really turned me on to at her end. We made a list of four or five different ideas, and this one came up and I don’t know where it came from, to be honest, but suddenly we were doing it. It took us almost two years to do it because of enormous amounts of delays and squeezing it in between other projects and things like that. Sadly it is coming out at a strange time as it was not meant to be any kind of tribute to her dying. It was finished before that. I feel a bit strange about it because people will be thinking we’re trying to cash in on her dying, and to get some sort of attention, which was never the idea. That was just coincidence. PB : When the Walkabouts do covers of other people’s songs they very rarely end up sounding like the original. You usually enhance them in a way. Have you done that again with this new album ? CE : Yeah, definitely. I have even written little liner notes for them saying that there are more like meditations, or mediations on what Nina Simone did. More or less we took the song, and started from there. I generally deliberately don’t even learn covers. I don’t sit there and try to pick out chords. On this album, there is a song, which Carla felt strongly that we should do at least chordly similar, so we did end up doing that on one of the five tracks. Generally they’re quite variant from the original though, and that’s the way they should be. The idea generally is to see how durable a song really is.I think in the most part the artists themselves appreciate a cover of a song that doesn’t reference the original. They are bored to death if you do their song exactly the same. There is no joy in it for them, but, if they hear a song done with a different sort of arrangement, or different sort of interpretation, that is really a turn-on. You realise that the song is actually bigger than you. PB : Do you feel that when you hear acts like the Willard Grant Conspiracy and Townes Van Zandt doing covers of your songs ? CE : We’ve not had a lot of cover songs done, five maybe recorded, but we have always been really lucky. When Townes did his cover of 'The Stopping Place', that was very odd, because the ‘Devil’s Road ’version is like a full scale rocker at least as far as the Walkabouts interpretation of rock goes, but his version had more of a balladic approach. Him doing it proved to me that I had stolen the song from him originally. It was so Townes like, even the words. I never really thought of referencing him at all, and then to hear him doing it it became so clear it was just a complete trip off. PB : You’re going to be releasing a 'Best Of’ compilation in Europe soon. You’ve just done that with 'Watermarks’. Why are you releasing another one ? CE : As we discussed earlier, a lot of these albums didn’t really come out in America.'Watermarks' was released predominantly for the American market, and then some of copies of it were imported. It was an American thing, and we thought that the European one should be different, not because of a marketing thing or that people should buy both of them or anything like that. I just thought that there was a specific set of songs we were in a way missing by not doing it in a different way. PB : Final question. The band’s going out on the road in Europe in October. What else can we expect from you in the near future ? CE : We have full plans to do another album next year. I’m more or less working on the songs right now. That will be the next thing. I am also finishing up a solo record at the moment. I don’t know when that is coming out. It’s always more a timing thing of when we can fit it in. PB : That will be on Glitterhouse ? CE : That will be on Glitterhouse. I recorded a mail order solo album, 'A Janela', for them a few years ago. The idea behind this one is to release it as a normal release, but we’ll see. I am going to finish it in the next month. I don’t know really when it is going to come out. PB : Thank you.

Picture Gallery:-

interviews |

|

Interview (2005) |

|

| The Walkabouts have just released 'Acetylene', their first album of original material in four years,and their loudest and angriest album to date. John Clarkson talks to frontman Chris Eckman about why after a decade they have gone back to their rock roots |

| Interview (2005) |

reviews |

|

Prague (2007) |

|

| Impressive and onvincing return to their rock roots by the Walkabouts on their new live album, 'Prague' |

| Acetylene (2005) |

| Shimmers (2003) |

most viewed articles

current edition

Carl Ewens - David Bowie 1964 to 1982 On Track: Every Album, Every SongArmory Show - Interview with Richard Jobson

John McKay - Interview

Colin Blunstone - Thalia Hall, Chicago, 16/7/2025

Billie Eilish - O2 Arena, London, 10/7/2025

Bathers - Photoscapes 1

Visor Fest - Valencia, Spain, 26/9/2025...27/9/2025

Loft - Interview

Sir Tim Rice - Interview

Robert Forster - Interview

previous editions

Manic Street Preachers - (Gig of a Lifetime) Millennium Stadium, Cardiff, December 1999Heavenly - P.U.N.K. Girl EP

Beautiful South - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

Oasis - Oasis, Earl's Court, London, 1995

Peter Perrett - In Dreams Begin Responsibilities Interview Part One

Boomtown Rats - Ten Songs That Made Me Love....

Coldplay - Wembley Arena. London, 16/8/2022

Prolapse - Interview

Pixies - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

Trudie Myerscough-Harris - Interview

most viewed reviews

current edition

Davey Woodward - Mumbo in the JumboSick Man of Europe - The Sick Man of Europe

Lucy Spraggan - Other Sides of the Moon

Amy Macdonald - Is This What You've Been Waiting For?

Phew, Erika Kobayashi,, Dieter Moebius - Radium Girls

Bush - I Beat Loneliness

Suzanne Vega - Flying With Angels

Alice Cooper - The Revenge of Alice Cooper

Blueboy - 2

Cynthia Erivo - I Forgive You

related articles |

|

: Interview (2023 |

|

| In the second part of our interview with guitarist Paul Austin, John Clarkson talks to him about songwriting with Robert Fisher from Willard Grant Conspiracy, Chris Eckman from The Walkabouts and Terri Pearson from The Transmissionary Six, and The Transmissionary Six's unusual new videos. |

Pennyblackmusic Regular Contributors

Adrian Janes

Amanda J. Window

Andrew Twambley

Anthony Dhanendran

Benjamin Howarth

Cila Warncke

Daniel Cressey

Darren Aston

Dastardly

Dave Goodwin

Denzil Watson

Dominic B. Simpson

Eoghan Lyng

Fiona Hutchings

Harry Sherriff

Helen Tipping

Jamie Rowland

John Clarkson

Julie Cruickshank

Kimberly Bright

Lisa Torem

Maarten Schiethart