Buffy Sainte-Marie - Interview

by Lisa Torem

published: 9 / 2 / 2018

intro

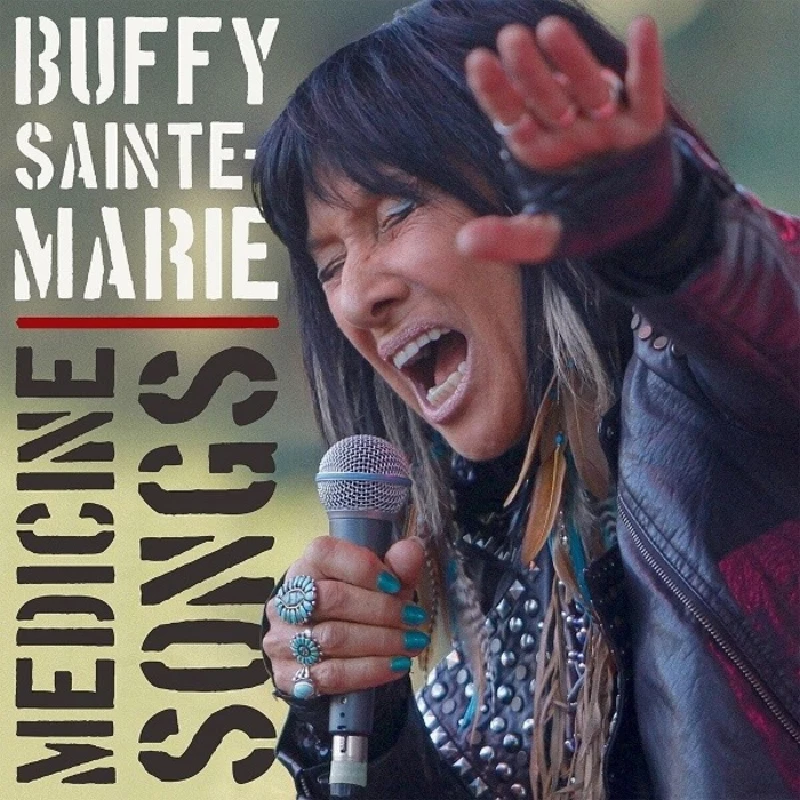

Canadian-born songwriter/performer and activist Buffy Sainte-Marie,speaks to Lisa Torem about her new album ‘Medicine Songs’

Buffy Sainte-Marie was born in the Piapot Reserve in Saskatchewan, Canada. Adopted by Caucasian parents, she was relatively sheltered from her Cree roots as a child but after returning to the reserve and forming strong alliances with her indigenous brothers and sisters, she worked tirelessly to educate others about the First Nation through her songwriting, concert appearances and educational outreach. Along the way, she earned a doctorate in the Fine Arts. She has been widely associated with the famed American folk movement of the 1960’s and 1970’s which originated around Greenwich Village in New York City and included the likes of Bob Dylan and Joni Mitchell, Buffy would ultimately attend college at the University of Massachusetts and keep pace with the likes of Taj Mahal as well. Passionate about her peoples’ struggles, she courted controversy with early ballads: ‘My Country ‘Tis of Thy People You’re Dying’ and ‘Now That The Buffalo’s Gone’, but she also attracted instant fans with the anti-war anthem ‘Universal Soldier’ (covered by Donovan) and the euphorically gentle ‘Until It’s Time for you to go’ (a major hit for Elvis in the UK) and ‘Cod’ine’ (covered by the Golden State’s Quicksilver Messenger Service), in which she chronicles an unanticipated addiction with prescription drugs in her early 20’s. Her career suffered setbacks when she discovered that American presidents Lyndon B. Johnson and Richard Nixon had congratulated radio stations that refused to play her controversial music. Prior to that occurrence, the prolific artist had turned out a minimum of an album per year of largely original music. Blacklisted but undefeated, Buffy refused to back down and to this day, at 76, continues to fight for environmental, cultural, educational and political causes. During a five-year stint on the American series ‘Sesame Street,’ Buffy had the opportunity to share the accomplishments of her proud culture with America’s curious children. She also publicly breast fed on one episode, opening the door for families, wishing to bring the then-taboo subject to light. Buffy achieved mainsteam success when she earned an Oscar for ‘Up Where We Belong’, a co-write with producer (then-husband) Jack Nitzsche and Will Jennings. This inspirational ballad served as the theme for the 1982 American 'An Officer and a Gentleman'. This certified Platinum/Grammy win was recorded as a duet by Joe Cocker and Jennifer Warnes and has become a much-requested staple in the great American Songbook and across the world. Over the last few years, through her recording projects for True North Records, Buffy has illustrated her unique gifts for telling sonic stories, gleaned from fact and fiction. After the widely anticipated re-release of ‘Running for the Drum’ in 2014, she followed up with her fifteenth studio album, ‘Power in the Blood’, released in May of the next year and produced by Michael Phllip Wojewoda, Jon Levine and Chris Birkett. That monumental work of pristine originals also included covers by British band Alabama 3 (Buffy discloses her collaboration with this band in the interview) and UB40’s ‘Sing Our Own Song’. 2017’s ‘Medicine Songs’ truly reflects this multi-talented performer’s attributes, as she painstakingly reimagines classics with contemporary bells and whistles, sanctions heartfelt ballads with simple accompaniment, and brings a couple of highly-energetic, politically-charged songs to the table. In her first Pennyblackmusic interview, Buffy reflects back on her remarkable career and inspires hope to a new generation of fans with ‘Medicine Songs’. We began by talking about her early songwriting and inspirations. “For me, it’s really two different things because songwriting and inspiration comes from my own life. The appreciation of, in particular, Joni (Mitchell) and Leonard (Cohen), that came about because I had heard their music and I thought that they were both terrific and the music business didn’t want to let them in, so I kind of took it upon myself to record their songs, tell people about them and talk about them in interviews, especially with Joni, because nobody was interested in Joni. I carried her cassette around in my purse for a long time and I played it for a lot of people, and finally the person who was interested was a junior agent, Chartoff Winkler, who was part of my agency. He wasn’t my agent, just a junior agent and I played him Joni’s music. He went down and saw her and they made a great career together. Joni was obviously so good and such a wonderful songwriter, but she couldn’t get anywhere. Show business can really work hard to keep you out”. I acknowledged that she recorded and reimagined earlier songs on ‘Medicine Songs’, in some cases, using contemporary recording techniques. To illustrate, I asked her to walk us through one or two songs and talk to us about what that process was like. “In the first place, the reason I made this album, it’s not like a compilation or a playlist of old albums, it’s not. I re-recorded new vocals and in some cases new instruments and new arrangements and other times I kept it exactly as I had recorded originally. ‘Universal Soldier’ is the best known of those songs, ‘Universal Soldier’ and ‘Now That the Buffalo’s Gone’, I did them exactly the same way that I did them originally, which I thought was right for them then and I think still is, with just acoustic me and a guitar, but other songs I changed quite a bit". Since the Donovan version was my first listen, I was curious about Buffy’s reaction to his interpretation. How did it come about? Did he do it justice? “He heard me sing it, that’s where he heard it. He heard me sing it in England. He jumped on it right away. He recorded both that and ‘Cod’ine’. And most people throughout the ‘60s and 70’s thought that Donovan wrote those two songs. I still have people argue with me and tell me that I didn’t write ‘Cod’ine’ and ‘Universal Soldier’ because they believed Donovan did. I don’t think that he ever said that he did. He’s a person of conscience and he only sings his own songs other than those two". Surprisingly another topic had come under scrutiny. It involved a song and a film. “‘Soldier Blue’ (‘She Used to Wanna be a Ballerina’, 1971) was a big hit in Europe, England, Japan and a lot of places, but (the film) was taken out of the theaters in the U.S. To me, the messages in all of the songs still make sense, including ‘Soldier Blue’, which is about loving your country, not like with nationalism and the patriarchy, not like with a Nazi salute and chanting, ‘USA,’ which has never thrilled me. The movie, ‘Soldier Blue’ is about a very violent incident and I wrote the song to be the opposite, to be in love with your country in a matriarchal way. It’s not so much patriotism and nationalism and wars, as it’s just the incredible beauty of nature and people living together in a great way but it really needed an update instrumentally so I did the best that I could with it". When the discussion floated back to the new album, Buffy exploded with passion for the new effects and ideologies that simmered beneath the surface. “‘You’ve Got to Run’ is nothing like either of the two songs which I just mentioned. It’s high energy. It’s about running, you’ve got to run for office, to keep the bozos from running the show or you’ve got to run a marathon for breast cancer awareness if that’s what you want to support in your community or in your life. It’s about being a champion at all levels, not just going for the prize and the trophy and the greed and the money but just being a champion from beginning to end. 'The War Racket’, on the other hand, is really, really right on the nose about war profiteering, it just doesn’t pull any punches at all but I kept it very, very simple. Instead of the big, huge arrangement like ‘You’ve Got to Run’ had. Tanya Tagaq is singing with me, and Jon Levine, who is a big producer of giant hits in L.A., all the way from Toronto, it’s a big, big record. 'The War Racket’, it sounds big, but it’s only me on keyboards and me on very simple guitar and my co-producer Chris Birkett on percussion so it’s real simple but it sounds big". Buffy was way ahead of her time in the field of vocal, electronic music. Her sixth album, ‘Illuminations’ was recorded in the winter of 1969 with producer Maynard Solomon, and on it, they utilized electronic synthesizers liberally. Furthermore, on ‘Better to Find Out Yourself’, her vocals are obscured by a Buchla synth. She elaborates… “There are all kinds of things that you learn how to do when you’ve had a studio in your house for a long time. I’d been kind of ahead of it in many ways before the industry was ready for electronics or vocal processing or strong lyrics. You know, it’s been pretty conservative most of the time. But now I think ears are ready to hear songs that are either about empowerment or protest, which are kind of the opposite. It’s not an album about protest, it’s about empowerment and protest. They really work together I think when people are looking for words—when they want to put their own feelings and views into words. People asked me after concerts, where can we get these songs? So I put them all together in one album". I was intrigued by a particular vocal style that, perhaps, harkened back to an indigenous tradition. It seemed most prevalent on ‘You’ve got to Run’ with Tanya Tagaq. “Well, there’s two things, if you’re talking about what we call “pow wow” singing, which is the part where the sound goes— (Buffy imitated the powerful utterances from the recording.) Was it like that?” I said yes. “I also used it in ‘Starwalker’ (‘Sweet America’, 1976) and a lot of other songs, like ‘No No Keshagesh’ (‘Running for the Drums,’ 2008). I started doing that in 1975, which was the first time I recorded it. It was the first time I recorded ‘Starwalker’ and it was the first time that I used that technique and it sounds like “pow wow” singing", REAL “pow wow” singing, what I learned from my uncles, just sitting around a drum, real “pow wow” singing is quite a bit different from what I do, but it’s very much in that same musical style. The words are not literal words, it’s more like telepathic emotions that people are singing, when we’re singing like that. I think that’s the style. Since you mentioned, ‘You’ve Got to Run,’ there is actually another indigenous style, a truer indigenous style, that Tanya’s doing. If you listen closely you’ll hear (Buffy pants quickly several times in succession). Some of them are guttural, some of them are real emotional; there are punctuating rhythms and Tanya’s very famous for that. She, too, comes from an indigenous background but she’s taken that style farther than anybody else up until now has taken it. So we’re not doing the same thing at all, even though we’re both indigenous. We’re doing two different elaborations on, how can I say it? indigenous styles?” I mentioned that over the years, it appeared that other artists had taken liberties with some of her songs by changing lyrics or adding verses or even funneling the songs into a completely different style or mood. I offered that Janis Joplin took such liberties on ‘Cod’ine’. How did that kind of thing go down with her? “I think it’s great (Laughs). If you can improve something, why not. If it ain’t broken, don’t fix it, but if you can improve it, please do. I think it’s great. It bothered me the first time when Elvis Presley and Bobby Darin and other Vegas singers—their musical directors changed the music, they changed the chord structure. They made it very vanilla. It bothered me. But you know what? You can’t kill a good song. It’s not like sculpture. You can’t break it. I did exactly the same thing, with Alabama Three. They wrote this real violent, warlike male aggression song, “There is power in the blood, justice in the sword” and they’re fans of mine and I’m a fan of theirs, and when we got together I said, 'Power in the blood' would make a great peace song. They said, “Yeah, sure.” But it did. And I changed the words with their blessings and I think it’s a more powerful song now than it was to begin with. I asked them, would they mind? If they had said no, don’t touch it, I wouldn’t have done it. Nobody asked me when they made changes. You win some, you lose some". We switched to a different genre. I explained how much I enjoyed ‘Until It’s Time for You to Go’. That was my first introduction to her songwriting. The lyrics are so accessible and evocative yet uncomplicated. How did she accomplish this feat? “Oh God, I don’t know. I don’t live a prescribed life, a life that’s been ladled for me by an education or a music school or a church or something like that. I think, maybe, I’m just kind of loose in my imagination and I’m fortunate enough to be among down-to-earth, real people part of the time, and of course, show business the rest of the time, which allows me to absorb the reality of the world. I just look at life in a big picture way, multi-generations and multi-nations. Traveling and coming up through the folk music traditions—that’s what was going on when I started out in show business. They were calling it folk music. I wasn’t a folk singer. I was a songwriter but I was around real folk songs that had lasted three or four hundred years and it was an incredible example for a young songwriter to be around these songs, and the reason why they lasted is because they were universal". “I’m so fortunate to have a real global perspective because of airplane tickets. I’ve often taken years off from careerism and just had a real life. I live on a farm. I’ve lived here for over fifty years with a whole bunch of animals. I think it’s a combination of the two. I have the helicopter vision of a person lucky enough to travel but I really do lay my bottom down on the ground a lot, gardening". Buffy touched on what it took to sustain herself all these years, but I wanted to know more. In a documentary about her life, she knelt in front of a group of hungry animals, talked to them sweetly and offered them food. Then she turned around and spoke about “…the quiet thing in me that replenishes the whole well…” Was she talking about a desire for harmony? Balance?” She paused. “I don’t remember saying that, but it sounds like me. The kind of life that I live and I have lived since the ‘60s has been a combination of show business and staying home on a farm in isolation. The best metaphor I can think of is a sponge. When I’m out, lights, camera, action, I’m giving something that people consider very precious, poetry and music and all that. People pay to come and see you. They like what you have to give but if you keep squeezing that sponge all the time, pretty soon the sponge wants to go home (Laughs) and refill. So what I’m refilling in that deep well is something that’s been natural to me since I was a kid. That’s why I think that all of my music and all of my concerts, even though some of the songs are very, very serious, there’s always a sense of playfulness in a concert, and positivity and empowerment. Even though some of the songs are dreadful and about genocide and murder and terrible things happening to people, it’s still a sense of empowerment and replenishment. That’s probably what I was thinking when I said that". Buffy had once been heavily involved in the Cradleboard Teaching Project, in which indigenous children, living on reserves, could connect via the Internet with peers from other locations, and where First Nation instructors could design and share related curriculum. Was this still on her radar? Buffy sighed. “No, that closed down a long time ago when George Bush came in and wanted to privatise all the foundations. No, that’s when I started considering going back on the road because I knew we couldn’t survive. It’s not as though we don’t exist but we’re just not operating at all at the moment. It’s the wrong climate for new projects. Even funders in Canada who really wanted to support “Truth and Reconciliation” and indigenous projects are not willing to come forward with new ideas or new startups. They just do funding in all the old ways: The opera, the ballet, the hierarchical models, the president and the vice president… They still want to do things in that old parliamentary way, and that’s fine, but it’s not good for startups and there’s no sense in my investing time in trying to be an administrator. The Cradleboard is like my album ‘Illuminations’ or writing songs and supporting artists that nobody knows about, The Cradleboard is like that. It’s very, very adventurous. It was very early for its time, putting kids togetheriIn the late ‘80s, and twinning schools". With the clock ticking and Buffy’s other phone ringing, it was time to wrap up. Looking ahead, I had heard that author Andrea Warren was working on a book about Buffy’s life. It was our final question, but the topic seemed to excite her. “She wrote the best, funniest book about women in the music business ever. It’s called, ‘We Ought to Know.’ She’s great. She’s a lot of fun. She came on the road with us, met my band and came to a bunch of concerts, and stood in the longest breadlines that the theater had ever seen. That’s going to be good, but when it comes out, who knows?” In my brief time, speaking with Buffy Sainte-Marie, we covered a lot of ground. She’s an effervescent, inspiration on so many levels. It was a true honour.

Band Links:-

http://buffysainte-marie.com/https://www.facebook.com/BuffySainteMarie/

https://twitter.com/buffystemarie

Picture Gallery:-

soundcloud

reviews |

|

Medicine Songs (2018) |

|

| Fantastic new album from Buffy Sainte-Marie which combines both unreleased songs with new versions of old songs |

most viewed articles

current edition

Carl Ewens - David Bowie 1964 to 1982 On Track: Every Album, Every SongArmory Show - Interview with Richard Jobson

John McKay - Interview

Colin Blunstone - Thalia Hall, Chicago, 16/7/2025

Bathers - Photoscapes 1

Billie Eilish - O2 Arena, London, 10/7/2025

Loft - Interview

Visor Fest - Valencia, Spain, 26/9/2025...27/9/2025

Sir Tim Rice - Interview

Robert Forster - Interview

previous editions

Manic Street Preachers - (Gig of a Lifetime) Millennium Stadium, Cardiff, December 1999Heavenly - P.U.N.K. Girl EP

Beautiful South - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

Peter Perrett - In Dreams Begin Responsibilities Interview Part One

Boomtown Rats - Ten Songs That Made Me Love....

Oasis - Oasis, Earl's Court, London, 1995

Coldplay - Wembley Arena. London, 16/8/2022

Prolapse - Interview

Trudie Myerscough-Harris - Interview

Pixies - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

most viewed reviews

current edition

Davey Woodward - Mumbo in the JumboSick Man of Europe - The Sick Man of Europe

Lucy Spraggan - Other Sides of the Moon

Amy Macdonald - Is This What You've Been Waiting For?

Suzanne Vega - Flying With Angels

Blueboy - 2

Bush - I Beat Loneliness

Phew, Erika Kobayashi,, Dieter Moebius - Radium Girls

Alice Cooper - The Revenge of Alice Cooper

Cynthia Erivo - I Forgive You

Pennyblackmusic Regular Contributors

Adrian Janes

Amanda J. Window

Andrew Twambley

Anthony Dhanendran

Benjamin Howarth

Cila Warncke

Daniel Cressey

Darren Aston

Dastardly

Dave Goodwin

Denzil Watson

Dominic B. Simpson

Eoghan Lyng

Fiona Hutchings

Harry Sherriff

Helen Tipping

Jamie Rowland

John Clarkson

Julie Cruickshank

Kimberly Bright

Lisa Torem

Maarten Schiethart