Willie Dixon - Interview

by Lisa Torem

published: 24 / 3 / 2013

intro

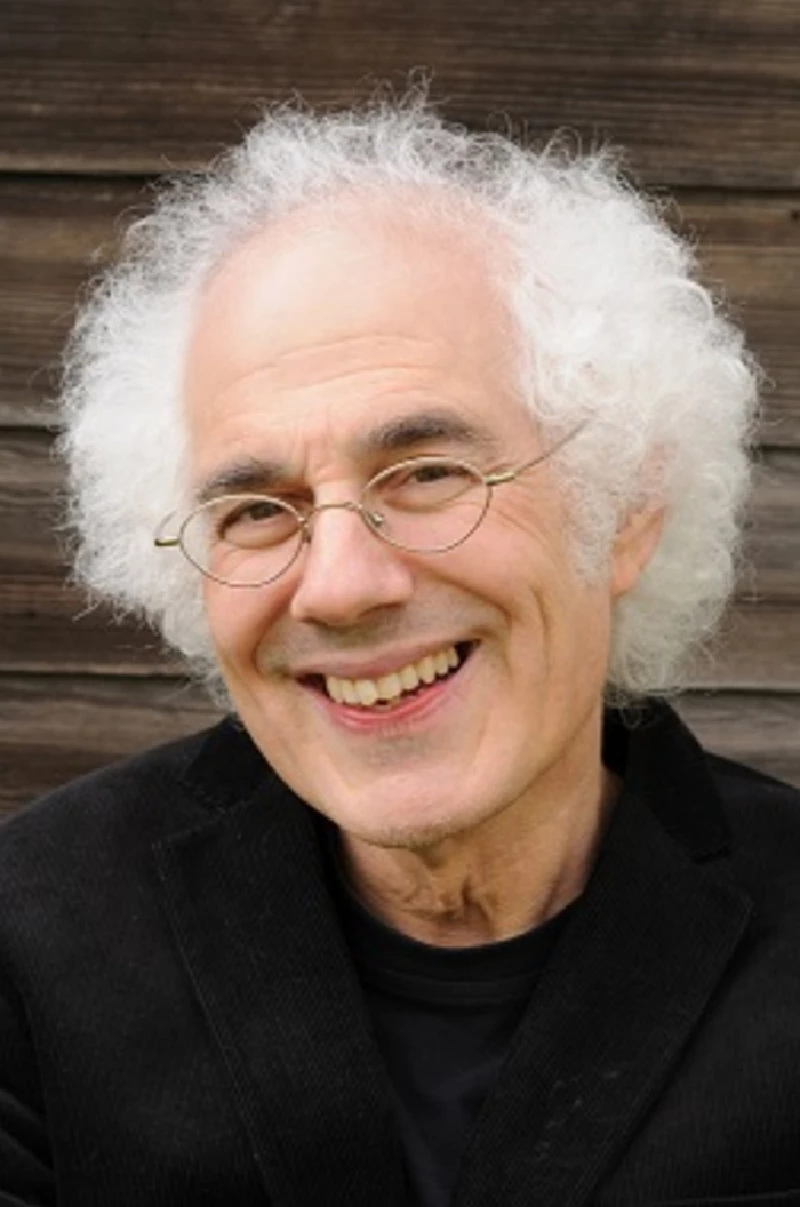

Lisa Torem talks to banjo-player and author Stephen Wade about his recent book, ‘The Beautiful Music All Around Us: Field Recordings and the American Experience’, which is about folk music of the 1930s and 1940s

Stephen Wade studied banjo with Fleming Brown in 1972 at Chicago’s Old Town School of Folk Music before teaching the instrument there himself. (By that time, the storyteller knew well haunts inhabited by Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf.) He established a strong connection with Brown’s banjo teacher, Kentucky-born WLS Barn Dance veteran, Doc Hopkins. Beginning in his teens, Wade served as Hopkins’s accompanist and remained close to both musicians to the ends of their lives. In 1979 Wade opened his celebrated one-man show, ‘Banjo Dancing’, which ran for more than a year in Chicago. In 1981 he brought it to Washington DC where it ran there for another ten years, before taking it back on the road. His ‘Catching the Music’ received a Regional Emmy nomination for Best Documentary in 1987. Wade received a Joseph Jefferson award for his second one-man show, ‘On the Way Home’. His recent 18-track ‘Banjo Diary: Lessons From Tradition’ [Smithsonian Folkways], is accompanied by a 44-page booklet, in which he describes relationships with Brown and Hopkins, and puts into historical context songs like, ‘Little Rabbit/Sheep Shell Corn’ and rags, ‘Alabama Jubilee/Down Yonder.’ Documentation of tunings and techniques used on each track are another bonus. It was nominated in the Best Album Notes category for the 55th Annual Grammy awards against the likes of records by Ray Charles, the Beatles and Janis Joplin – Wade was the only artist who had penned his own notes. In his well-researched ‘The Beautiful Music All Around Us: Field Recordings and the American Experience’, Wade, fascinated by artists he heard on Library of Congress field recordings from the 1930s and 1940s, dug more directly into their pasts. Loaded with cultural anecdotes, personal reflections and vivid examples of how gifted American roots musicians influenced subsequent generations, ‘The Beautiful Music…’ is a dynamic, introspective read appealing to both ethnomusicologists or simply those readers who relish a spirited field holler. Before leaving Washington DC for a multi-city tour, Wade spoke to Pennyblackmusic about his passion for preserving and performing traditional music, his love affair with the banjo and his latest recording. PB: You started out playing the guitar, so what was it about the banjo that captured and has held your interest all these years? SW: I imagine that if I could have started out with the banjo then I probably would have. I’m just so drawn to Southern music. At the same time, I love the guitar just as much with its possibilities and challenges. I don’t really favour one over the other. Luckily for me growing up, I got to hear a lot of performers on either instrument, no matter whether they played blues, hoedowns or church songs. Just as much, I gravitated to the settings where all this occurred; not just the music, but also the wider experiences that housed this creativity. Here I’m referring to the listeners as well, and to the sidewalks and street corners, taverns and storefronts where they all met. PB: In your book, you wrote about trying to locate people who knew about the work of the artists on the field recordings. Sometimes it seemed like you were on a “wild goose chase.” How challenging was it and how long did it take to complete your research? SW: I never thought of this effort as a wild goose chase! That never even occurred to me. That’s not to say that every lead paid off, or that answers always came readily or immediately. Sometimes people knew in advance who it was I wanted to find, but they held back in sharing that information. One fellow later told me--and with a smile--that he wanted to make sure I wasn’t an axe murderer! That makes sense, really, that people were protective of their neighbours, many of whom were quite elderly. (LT: In his book, Wade cites, for instance,”…Someone stopped over, peering hard through the doorway for signs of danger. Though Luella lived on a near-empty street with just a few shuttered houses, her Byhalia, Mississippi, neighborhood stayed watchful on her behalf.”) Elsewhere in the book, he describes how the interviewee coped with a stranger coming into her home: (“…Mrs. Hunter sat with her terrier poodle in her lap, quietly stroking the dog with one hand. As I got up to leave, she took her other hand from her pocket, drawing with it an unholstered, snub-nosed, .38-calibre revolver. I suddenly realized that the whole time we talked she had it pointed at me. She revealed it now as a statement of trust.”). Then there were those attempts I made in another community in the Mississippi Delta when all my face-to-face contacts there had failed. So, at the recommendation of someone who remembered that performer from the 1940s, I took out a classified ad in the daily paper, set up an 800 number and ran a continuous roll on the local cable access channel for a month. All that remained mute for three weeks, and then, with just a week’s life left in these efforts, four calls from the same person came in. She was a first cousin of the performer and knew him very well indeed. The truth is that each chapter, each song, each performer made its own demands, and each one of those journeys differed. But again, no efforts seemed wasted or pointless. In truth, I actually researched the thirty songs and artists on the book’s antecedent project, the album called ‘A Treasury of Library of Congress Field Recordings’ (Rounder 1500, 1997) and not just the baker’s dozen in the book. This effort took eighteen years from start to finish. I started, as a rule, with very little information on the performers, and physically began (after reading relevant letters and surviving documents) by venturing back to the places where the recordings took place and working out from there. (LT: In his book Wade writes how, after hearing the recordings, he wondered: “Where had these singers and musicians gone? Who were they, beyond a few words possibly spoken on a smattering of discs? What were their lives?”) This kind of work just takes a lot of approaches, and not every lead works. Folklorist Archie Green knew well the joys, serendipities and elation as well as the frustrations, lost memories and inevitable incompleteness of folksong study. But in the end, Archie, mentor to this book, exemplary scholar and dear friend, also counseled me to just "enjoy your scholarship." So, frustrations are just part of the calling, but sometimes things work well too. No matter what, I always had to reach some degree of critical mass for each study, each story. Sometimes I just had to keep going back to find that sense of fullness. I never actually knew what the story was in advance. As my old friend, author Jack Conroy, told me about his own autobiographical writing: life had to furnish the plot. PB: Bozie Sturdivant’s vocals on ‘Ain’t No Grave Can Hold My Body Down’ were remarkable. Did you have a sense of who Bozie was when you heard that recording? What other recordings made an immediate impression on you? SW: Yes, I’m so glad that Bozie’s vocals matter to you too. He’s truly remarkable. Again, I knew nothing about him when I first heard him. Just that he seemingly harnessed the potential of the human vocal apparatus in service to some amazing and moving poetry. There was essentially no information about him at the Library, and their earlier efforts to seek him had gone unrewarded. I also found so little, at first, in Clarksdale. Happily, that changed in his case, and I was able to learn something about him. As for your second question, the answer is that all the songs and tunes I picked both here in the book and earlier on the ‘Treasury’ made deep and abiding impressions on me. PB: ‘Coal Creek March’ was originally written for the miners and the hardships they endured, wasn’t it? You describe the historical events surrounding the song in vivid detail. If one hears the song as a recording or concert piece these days, the story might lie in the shadows. Does that bother you? SW: I don’t think your saying that ‘Coal Creek March’ was written for the miners is as correct as perhaps recognizing it had a pre-existing musical life that became adapted to the tragedies that had beset that community. But, as I trace in that chapter, it shifts as it becomes more distant from that place and time. And it reflects too ragtime elements emerging in popular music at the century’s turn that rural players incorporated. Well, as for a story of this piece and its historical context, I know that whenever I’ve made live presentations that this story emerges. And, also, in considering your question, didn’t Pete Seeger make reference to the “March” and its past repeatedly in his concerts and recordings? So, I don’t think that past is so much concealed as it might just be submerged in the present day. PB: The 1934 version of ‘Rock Island Line’ recorded by Kelly Pace and group also appears. How do you compare that version to those later recorded by Leadbelly or Lonnie Donegan? SW: I discuss these musical differences, one being a quartet song and its traditions, and the other a worksong/cantefable in the same chapter. I guess the really new news in the chapter was my finding the original version, the one written in Little Rock by the engine wiper. I must tell you that was quite a moment. I realized immediately what I was looking at, and, when I tried to phone my editor to tell her the news of the discovery, my hands shook so hard that it took three tries on a touchtone phone to complete the call. That was really a once-in-a-lifetime experience. Sort of like your question about wild goose chases, I had no idea if I’d find something. I just knew from the two 1934 field recordings that the song must have had a life prior to those recordings. The question became then, if so, then who might reasonably have commented on it? Once I found out there was a Rock Island railroad magazine, I made arrangements to see it. Cartons and cartons arrived. There were years of issues, all thick and all set in small type. I really didn’t know if I’d find anything at all. But from the start I learned about the railroad and that time. I also started finding other booster songs, as this was called too, and then researched other industries that had similar efforts. Various steel works, coal mines, iron foundries and railroad lines sponsored quartets back then just as construction companies nowadays host soccer teams for solidarity and publicity both. PB: What was the most rewarding experience you had writing and researching the book and what kind of audience do you hope it will attract? SW: Certainly at this time the feelings shared with me by family members and other first-person contributors about their appreciation for the book has been utterly rewarding. Since it has come out I’ve been “bringing the book back home,” returning to the communities where I did my research. I’ve found this enormously fulfilling. Prior to all this, there have been so many rewarding experiences. As for its audience, I just hope that readers from all over, of various backgrounds and interests, will find these stories rewarding. PB: Some people still remember kids in the neighborhood playing hand clapping and jump rope games, which involved rhythmic chanting. In your book, you cite examples of chants like ‘Sea Lion Woman’ (Christine and Katherine Shipp) and ‘Pullin’ the Skiff’ (Ora Dell Graham). Do you recall chants like this when you were growing up? SW: Kids still play these games. Look at the front page of ‘The Washington Post’, Feb. 27, 2013, “An old-time hand-clapping game comes full circle—and goes viral.” That tells us something, doesn’t it! And yes, I recall games like those growing up. While I didn’t do jump rope rhymes or heard these particular pieces, I sure heard rhymes of that sort. I bet you did too! PB: Is this type of casual activity in danger of becoming a lost art without people like you or Alan Lomax there to research or record such practices? SW: No. Informal culture, kids’ games, folklore – all this goes on with or without the documentarians! Thank heavens, too. PB: How did you come up with the theme for your CD? Are there banjo tunes a player is obligated to learn? SW: I don’t think there are any obligatory tunes, so much as certain standard ones. But that varies with style and region. Certainly bluegrass players often tackle ‘Foggy Mountain Breakdown’ early on, while old-time players might cleave to ‘Sally Ann’ or ‘Cripple Creek’ from the start. Earl Scruggs cited ‘Old Reuben’ as his breakthrough tune when he was still a boy. Originally I thought I’d do an album on Washington DC’s banjo history. It reaches well into the nineteenth century, further evidenced by recordings made here before the century’s turn. I thought that since I live there and since my book approaches creativity that’s both local and everywhere, that this locale might provide a good focus. But as I worked through that history, I realized if I were to record such an album, that I’d really need to be a bluegrass singer, and I’m not. This is a city not only of Duke Ellington, but also John Duffey. So I shifted focus and realized that another convergence with my book (which was then about to go into production, a process that occupied fully a year) was how I learned music in the first place—and as I said there in the album notes and the book’s preface—that face-to-face process was inspired by these very recordings. So it all made sense. You can probably tell from the notes that I’ve been thinking about many of these numbers for years, so I was able to cobble together a list of songs pretty readily. I had ideas about their arrangements and then visited one-by-one my colleagues to go through them and see what worked best. Then we began ensemble rehearsals. PB: Had you worked with musicians Mike Craver, Russ Hooper, Danny Knicely, James Leva and Zan McLeod previously? SW: Yes, I’ve played with them before. I’ve been recording with Mike Craver since the early 1980s and he’s on all my albums. I’ve recorded with Zan since 1990. I first saw James in 1975, but didn’t start to play with him until 2005. I put together a group that year –James, Zan, and Mike—towards this very end. Specifically, that group began on behalf of another project I did (also for Smithsonian Folkways). It’s called ‘Hobart Smith, In Sacred Trust: The 1963 Fleming Brown Tapes’. Anyway, I put together this ensemble—it took four of us to do what Hobart could do all by himself—and we played at several places where he had performed in years past. I wrote a three-hour, slide show-illustrated piece that I varied quite a bit depending on Hobart’s past connections to wherever we were. On another level, it was Hobart too who appeared on early LC recordings that got Fleming Brown to play, and so the radiations of his influence come back to the book as well as to this album. Because when I put this group together, I knew I’d want to do something like this when time came that my book would emerge. In the interim I met Danny and Russ, and knew that they’d have to be part of all this too. And Danny plays in a group with James, and on and on…. PB: What did you learn from Doc Hopkins and other musicians of his generation? SW: That’s a huge question. I try to reckon with their legacy throughout the notes to ‘Banjo Diary: Lessons from Tradition’. I also explore these lessons in my 1987 public television film, ‘Catching the Music’ (found on folkstreams.net). I guess if you pressed me for one answer it might be this, and here I’m referring specifically to Fleming, but thinking also of his teacher, Doc Hopkins, and so many others too. This statement below concludes an essay I wrote back in 1995 for ‘The Journal of Country Music’. I titled it ‘The Conduit’ for that was a term Fleming Brown used to describe himself. He also spoke of his being an “amateur”, not just because of his vocation as a commercial artist, but because of the word’s root association with an idea of love. In remaining an amateur and in not becoming a professional musician, Fleming felt he could sustain his involvement with the music purely on that level of choice, rather than need: “Traditional music is an art form that, like all art forms, depends on subtlety. A tune has recognizable contours, yet becomes more genuinely alive in the personal solutions brought by its individual practitioners. It is given to us freely, and is “published” in the Public Domain. It persists because of love and respect. It is cherished and remembered by old people, catalogued and conserved by scholars, saved and affirmed by fans. Discs left in a hatbox, records found at a yard sale, instruments taken from a closet, recordings made at home—all of these survivals result from an ethic of taking care. Traditional music cannot be hoarded, for that is to conceal the work of past players, and it must not be stolen, for that is to sever connection from them. The music can be learned, but without commitment it cannot be played well. It requires devotion and responsibility, wholeheartedness and intelligence.” “The lessons my teacher gave me came from another time, almost another world. He also gave me his banjo. It marks a special moment in my life, but Fleming’s banjo is merely on loan to me, and someday it must belong to someone else. In that, it is like the music itself. We are fortunate there is a body of traditional music to inspire us, and that it is capacious enough that we can enter into it and make it our own. But we are all conduits, and at heart, we are all amateurs.” PB: In the booklet accompanying the CD, you discuss the evolution of songs like ‘Santa Anna’s Retreat’ when performed by different generations of artists. Can you discuss how a song “evolves”? SW: Time and again we see changes as tunes pass from one player to another, let alone in arrangements and settings. I didn’t use the word “evolution” per se with ‘Santa Anna’, but the wonder I felt with respect to this piece had to do with the sheer directness of contact it represents: three named individuals carrying this tune from the Mexican war to one another to the present day. I just think that’s astonishing. As for “evolves,” I think we best look at each song on a case-by-case basis and see how each one changes. In the book I quote scholar Norm Cohen who addresses this matter so well. He talks about the matter of possession, of how these pieces reshape according to who's singing them. Certainly earlier you picked up on this with ‘Rock Island Line’ shifting from a quartet song into Leadbelly’s rendition and thence into popular music. I guess that whole discussion I get into in ‘Diamond Joe’ addresses this matter too, as does the discussion of ‘Glory in the Meetinghouse’ or ‘Goodbye, Old Paint’ – of how Jess Morris’ version got to Tex Ritter and thence to Aaron Copland. Really, this creativity that’s both individual and social is central to folk music and to this book. I often think of that great quote from Phillips Barry: “Every folk singer is a folk composer.” We have here created works for which many bear artistic responsibility. PB: You travelled often to learn tunes from older musicians. It seems all concerned gave freely of their talents and skills. Currently, many people are concerned about copyright issues and lawsuits. Are those carefree days of sharing gone? SW: No, those are different matters. Traditional and informal expression and sharing still go on. They rely on what economists these days term “a gift exchange.” The other kind, which also exists, and to which you draw attention here is often termed “a commodity exchange.” As you know, the latter operates under legal regulations, while the former may crop up in personal relationships. Evolving approaches to shared knowledge and the internet speak to these matters today, as do current meetings at UNESCO regarding intangible cultural properties that mark a given nation’s patrimony and debates over those property rights. PB: Thank you. http://www.press.uillinois.edu/wordpress/?p=9518 http://www.press.uillinois.edu/books/catalog/55qpr7zm9780252036880.html http://www.folkways.si.edu/stephen-wade/banjo-diary-lessons-from-tradition/american-folk-old-time-bluegrass/music/album/smithsonian

Picture Gallery:-

reviews |

|

Live in Chicago,1974 (2019) |

|

| Live 1974 album from Willie Dixon proves to be a clear window into the music of one of the great songwriters and legends of Chicago blues |

most viewed articles

current edition

Carl Ewens - David Bowie 1964 to 1982 On Track: Every Album, Every SongBathers - Photoscapes 2

John McKay - Interview

Editorial - July 2025

Billie Eilish - O2 Arena, London, 10/7/2025

Simian Life - Interview

the black watch - Interview

Chris Wade - Interview

Cathode Ray - Interview

Sir Tim Rice - Interview

previous editions

Heavenly - P.U.N.K. Girl EPTrudie Myerscough-Harris - Interview

Pixies - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

Boomtown Rats - Ten Songs That Made Me Love....

Fall - Hex Enduction Hour

Peter Paul and Mary - Interview with Peter Yarrow

Sam Brown - Interview Part 2

And Also The Trees - Eventim Apollo, London, 21/12/2014.

Place to Bury Strangers - Interview

Miscellaneous - Charity Appeal

most viewed reviews

current edition

Sick Man of Europe - The Sick Man of EuropeAmy Macdonald - Is This What You've Been Waiting For?

Phew, Erika Kobayashi,, Dieter Moebius - Radium Girls

Alice Cooper - The Revenge of Alice Cooper

Blueboy - 2

Lucy Spraggan - Other Sides of the Moon

Cynthia Erivo - I Forgive You

Bush - I Beat Loneliness

Davey Woodward - Mumbo in the Jumbo

Philip Jeays - Victoria

Pennyblackmusic Regular Contributors

Adrian Janes

Amanda J. Window

Andrew Twambley

Anthony Dhanendran

Benjamin Howarth

Cila Warncke

Daniel Cressey

Darren Aston

Dastardly

Dave Goodwin

Denzil Watson

Dominic B. Simpson

Eoghan Lyng

Fiona Hutchings

Harry Sherriff

Helen Tipping

Jamie Rowland

John Clarkson

Julie Cruickshank

Kimberly Bright

Lisa Torem

Maarten Schiethart