Jimmy Webb - Interview

by Lisa Torem

published: 15 / 1 / 2012

intro

Jimmy Webb speaks to Lisa Torem about songs such as 'Wichita Lineman', 'Galveston', 'The Highwayman' and 'MacArthur Park', his many musical collaborations and what makes good songwriting

The list of recording artists who have been bit by the ingenious Jimmy Webb bug includes Glen Campbell, Art Garfunkel, Linda Ronstadt, Joe Cocker, Frank Sinatra and Donna Summer. The Oklahoma-born son of a minister began his career in the 1960s, as a teenager, providing sophisticated covers for pop, rock and disco performers. Many of Jimmy Webb’s songs, such as ‘MacArthur’s Park,’ ‘Galveston,’ and ‘Wichita Lineman’, have become international hits and American staples: In the 1970s he became a singer-songwriter himself, knocking out six albums in eleven years; he garnered Grammys for performing, songwriting and composition and became the recipient of the National Academy of Songwriters Lifetime Achievement Award. In our first Pennyblackmusic interview a year and a half ago, Jimmy let loose facts about his adventurous spirit: the list included scuba diving and having fantasies about finding buried treasures. But in this intimate chat Jimmy went more below the surface, rendering tales about his working-class roots, his binding friendships, zeal for the studio and meeting his many fans, face to face. This Jimmy finds as much pleasure in a rolling passenger train as he once did in a high-speed jet. This second interview strikes very close to home. My own father was a piano player who suffered from Alzheimer’s Disease. One beautiful night we attended an intimate concert, such as the kind Jimmy is embarking on currently. Being purists, we loved Jimmy’s ability to entertain simply – sans pyrotechnics and state-of-the-art tomfoolery. The nightclub glistened by virtue of his solid and evocative voice, profound lyrics, and uplifting chords. Like so many fans that came before and after us, we were greatly moved by his honest performance and a shared tale that would become family legend. PB: The song, ‘Wichita Lineman’, includes the lyrics, “I know I need a small vacation, but it don’t look like rain/And if it snows that stretch down south won’t ever stand the strain.” Tell me what you meant by that. JW: It’s just about the guys working on the wires. He’s not going to be able to take a vacation unless it rains, and “if it snows that stretch down south won’t ever stand the strain” –a weak part in the whine, if it snows, it could fail, so it’s something on his mind that he’s worried about. These are things that a telephone repairman or a guy who works on high-tension wires thinks about. PB: ‘Wichita Lineman’ is such an important song because it gives a lot of credibility to the people that many of us grew up with. Has anyone in the trades ever come up after a show to express how this song made him feel? JW: Not in so many words, but there is a tremendous group of fans and people who I see on a regular basis, because usually after a performance I go out and greet people. To tell you the truth, this is one of the most enjoyable things about performing. For the most part they are working class fellows – people that I just enjoy shaking hands with. Occasionally, somebody will say, “My father was a lineman.” It definitely does come up in conversations with these people. Twice, I’ve had these guys come up to me. One of them was a crewman on the Wichita, which was the name of the destroyer and Galveston was the name of the destroyer tender. When they would meet up to refuel and convey mail over from the tender to the destroyer – this was the Tonkin Golf, during the Vietnam War. Each ship had a theme song. So the Galveston would play ‘Galveston’ as loudly as possible and the Wichita would play ‘Wichita Lineman’ as loudly as possible. Moments like that are very moving to me because they relate so specifically to some very dramatic events in other peoples’ lives. So that’s my character – the guy in ‘Galveston’ is an ordinary guy and Galveston was chosen because it’s a blue-collar town. It’s not the Riviera, it’s not Hollywood, it’s not New York. I would say that that’s the palette, that for a long time, I was working in. Maybe I still am. Even though sometimes I’m writing about Gauguin, I write about him from a perspective that I really can’t escape. I’m drawing parallels between a guy who was born and raised in Oklahoma and Gauguin. It’s a terrible expression, but that’s where I’m coming from. You can take the boy out of the country, but you can’t take the country out of the boy. PB: Since we’ve last spoken, so much has happened. You’ve released the ‘Just Across the River’ project, which featured duets with other seasoned songwriters and vocalists. What were the highlights? JW: It would be really hard for me to pull one of those off from there, for political reasons – I’d be in so much trouble. First of all, I’d like to say, most sincerely, that it was one of the most enjoyable things I’ve ever done musically in my life. To duet with Billy Joel, to work with Mark Knopfler and Jackson Brown, Lucinda Williams: everybody on that record, each person was a joy and a jewel onto itself. It was a choice experience, something to be remembered forever, but there was one historical recording that took place on the album - which was Glen Campbell and I singing, ‘By the Time I Get to Phoenix,’ and, first of all, I think it came out really nicely. But it was also the only time he and I have ever performed on record. We did a wonderful concert at the SchermerHorn (Symphony Center, Nashville-LT) - if I may be so bold, it was the talk of the town. He did so well that night. Early the next morning, we were in the studio trying to grab this historic performance, because we really don’t know how much longer Glen is going to be performing. We were able to get that and, for me, it’s almost a heartrending moment when Glen comes in on the second verse and sings, “I know I need a small vacation, but it don’t look like rain…” I think that’s one of the most memorable moments of the record for me. It also tells you why he does the singing and I do the writing. PB: And why is that? JW: Because he knows how to sing (Laughs.) PB: Some would argue with that statement. Will you do a follow-up? JW: Well, we have done it – it’s not finished, but I just spent five or six days in Nashville finishing my vocals, and then I did a concert at the Bull Run Tavern in Leominster, Massachusetts. One thing in my life that is very, very positive right now is that my voice continues to develop. It’s a completely weird thing that’s going on. I was a completely late bloomer vocally, but my voice keeps getting stronger and stronger and better and better. I’ve heard the vocals and I know that I sing better on the second album than the first. But the minor points, in terms of choosing who will be involved, specific pieces of material, that’s still kind of in the shadows. I don’t know whether we’re ready to uncover - some of these people would be taken a little aback to see this announced, but I could probably safely say that Keith Urban would appear on this album with us, and everybody that will appear on the album will be in the same league, and so it should be spectacular. PB: And will you be writing some more originals for the album? JW: There’ll be a couple of originals. ‘Rider From Nowhere’ which I did with the band, America, is one. We have some really interesting ideas, but not ones that have all been worked out yet. As you know, on the first album, there was some brilliant matching of material with artist and arrangement and a superlative production from Fred Mollin who has been my Svengali and alter ego. We made my record, ‘Ten Easy Pieces’, in his garage in Toronto. He’s just extraordinary and he’s just recording everybody, and, thank goodness, he still has time to do my records as well. PB: You also collaborated with a young artist, Nikki Jean, known for her hip-hop associations with Lupe Fiasco, for her debut album, ‘Pennies in a Jar’. You don’t generally collaborate. What motivated you to do that? JW: What motivated me to do that was that Marty Bandier (CEO Sony/ATV Music Publishing) looked me right in the eye and said, “I’d like for you to do this project, Jimmy.” (Laughs.) That’s the honest answer. Then I got to know Nikki Jean and she’s a winner and she’s a charmer, and she got it into her head that she wanted to do this album with a group of songwriters – I suppose it wouldn’t be too immodest of me to say – that she admires. And it turned out to be really a bunch of guys that I know. I serve on the ASCAP Board with them or I serve on the Songwriter’s Hall of Fame Board with them. It was Hal David, Paul Williams, Barry and Cynthia Weil. Don Schwartz was another of those guys. Nikki really set her sights high and I’m at a loss as to how she was able to get this done. She’s a really tenacious and an admirable, gorgeous young woman of the best character. So I really think that took her a long way – her genuine goodness got her over the rough spots. There’s no kind of hype that could have put this thing together. There’s a very funny thing about the song I wrote with her, ‘China.’ I called her up one day because she had given me some lyrics. I told her that I think I could get into this song. I said, “I’m a collector.” She said, “Oh, really?” Because unbeknownst to her, I collect Italian glass from Murano. Actually, they’re like glass aquariums with fish swimming in them. They are from the 1940s and 1950s and I’m crazy about them. I’ve now filled up the house with them and I can’t have anymore. My wife told me that I can’t have anymore. I also dabble in Concorde memorabilia that was a plane I flew in that I was crazy about. I actually have a few seats out of the Concorde and some of the instruments. My grandpa was a collector – it’s in the blood. And I was thinking about China and the lyric seemed to fit that scenario perfectly well. Every once in a while, I buy some China for my wife. I bought a serving tray, for example, that was taken off the Lusitania before she sank. So I got together with Nikki Jean and we were writing ‘China’, and I told her that I love collecting and she kept looking at me very strangely, and finally I told her that I love Dresden China, and she asked, “Do you know what this lyric is about?” “Yes. I assume it’s about the ethos of collecting,” I said. She said, “No. no. no. The song is about China – you know, China, like the country.” She was kind of looking at me, like, “What the fuck?”(Laughs) After I got that straightened out, the rest of it was easy. But she’s very political, and to tell you the truth, then I really got excited. We’re going to do a good, old 1960 political song here, something that’s really going on in the world. That got me a lot more excited, to tell you the truth. I think it turned out really well and I’ve had some really good comments on the song. PB: You went on a “Masters of American Song” train ride with songwriters, Jesse Winchester and Tom Russell, across the state of California, this year. Conducting songwriting workshops and being on a passenger car with your fans for several days sounds like a pretty, intense experience. Were you able to get to know your fans more intimately? Besides the spectacular scenery, was that the whole idea? JW: I love trains, and for me, primarily, I think I’ve already tipped my hat. Give me a chance to get on an old train or a plane, or a boat or something, and anytime I can relive part of the American experience, I’m probably going to be there, especially if I’m getting paid. I’ve always loved the fan experience. It’s always been good for me. I’ve never had anybody run up to me and say, “I’m going to kill you because I don’t understand ‘MacArthur Park,’ and I’m going to make you regret it if it’s the last thing I do.” I think sometimes it might happen, but it’s never happened before. If it’s anything under a 400 seater, I try to go out after the show and spend some time with my fans and, frankly, there’s not enough money in the merchandise part of things to make me stand there for an hour and a half. The only thing that would make me stand there for an hour and a half is the exchange of energy with the actual human beings that are there. They all have some spiritual nugget of inspiration, a coal or fire that they want to pass over to me. They want to let me know that I’ve done something important in their lives, and what can be more invigorating, and even flattering, than to talk to people that think you’re the greatest thing in the world? On the surface that is a brilliant experience, but if you dig a little bit deeper and someone says to you, “Last year our granddad died and he wanted, specifically, for ‘The Highwayman’ to be played at his funeral,” then the conversation starts becoming more meaningful and more soul searching. All of a sudden, you’re running through the lyrics and thinking, “Was that good for a funeral?” A couple came up to me, one night, after a show. They were very proud. They said, “We want you to know, ‘MacArthur Park’ was our wedding song” (Laughs). “It was? Oh, my!” (Jimmy sings the dramatic line from the song, “Oh, noooo.”) PB: At the Country Music Awards in November, Glen Campbell was given a touching tribute. But some fans are asking why Glen was not asked to perform. Secondly, in regards to Alzheimer’s disease, which Glen has stated he has, this is going to become so much more of a reality within the music community. How do you see this affecting us? JW: I think we’re going to be looking at a widespread, almost epidemic of Alzheimer’s. In our generation it’s probably going to be difficult because, of all the diseases that are killers, this is the most insidious, and it takes the longest to do the job and it’s hardest on the families, in terms of being a stress generator. What has happened with the Glen Campbell family is that they have decided not only to go public with this story, but to video graph it – to turn it into a documentary, which the film director and actor James Keach , who is renowned for his work in this area, will be covering - he’s going to be covering Glen’s never-ending tour, until it ends. That’s one aspect of it. We’re all going to be dealing with it or know someone who is dealing with it. It’s something we should start learning about now and preparing ourselves for. PB: Some fans were wondering if Glen Campbell wasn’t asked to perform at the Awards ceremony because he had admitted to being in the early stages of the disease, earlier that year. JW: There was a lovely moment in the CMA Awards and Brad Paisley, Keith Urban and Vince Gill all did a spectacular job of their particular versions of Glen Campbell’s songs. I was sitting at the piano – which was actually a muted piano, since there was no piano on the track. I was just sitting there, waiting to come down off the stage and greet Glen, and all it was meant to be was that Glen would come up and say, “Hello.” It was the 50th Anniversary of Ovation Guitars. So they were giving away Ovation guitars. There were Ovation guitars backstage. I must have signed fifteen or twenty Ovation guitars myself. There was just a lot of Ovation stuff going on. Then Vince Gill, who is the nicest guy there is, in the world, went down, as we were all gathered around there, hugging Glen and shaking hands, as we were saying, “Isn’t this a great moment?” And as for something that Vince did very innocently, I don’t think it would have gone any further than that…it would have been the end of the story. But Vince, very innocently, handed Glen the Ovation guitar, he was holding in his hand, and Glen took it and started tuning it up to get ready to play a song, and probably knowing how production personnel are, during an event like this, they probably went a little bit apoplectic, when they thought that Glen was going to start singing the song, and so I think they kind of truncated a moment that probably should have lingered a little bit longer. I’m not sure exactly what happened, because I didn’t see it. I just know that I’ve been asked about it so much. I know that something happened. But the only thing that I can think that it was about was that Glen took the guitar, and all Glen knows is; you hand him a guitar and he starts singing and playing, and he still does it extremely well. He was saying to me, at the time, “What key are we in Jimmy, what key are we in?” I didn’t know what key we were in. I was teasing him and I said, “It don’t make any difference. Just play any key you want to…” I don’t think anyone onstage had any sense of anything having gone wrong. But for some reason, the overwhelming reaction has been that something went wrong. So many people have asked me about this incident and I still don’t know what it’s about. I know there was no time for Glen to do a song. He was just going to come up and greet the audience. PB: Oliver Sacks has said: “The past, which is not recoverable in any other way, seems to be sort of ‘embedded in amber.’” I believe he is referring to the important role music plays in the life of one who has lost his memory. Now if Glen, or any artist, makes a public declaration, and then performs and forgets lyrics, should we judge him or her by the same performance standards as we would other artists, or do we need to adjust to that artist’s current state? In other words, because studies show that Alzheimer’s patients have a great capacity to derive emotion from music, should the songwriting community and audience develop more tolerance? JW: You’re referencing here the Glen Campbell tour and the mixed reaction, aren’t you? There have been some incredibly positive reactions to Glen’s performances. He has good nights and he has nights where he doesn’t feel that he has done as well, so I think it has to do with which night you happen to be there. But I tend to see this as kind of a one-off. I don’t think we’re going to see a lot of Alzheimer touring. I think Glen is unique in a sense that he’s still able to function at a high enough level to do a concert. I’m trying to be delicate, but most people would not be able to do what he’s doing, and a lot of it is reflexive and a lot of it is just learned behaviour that is so firmly ingrained and hardwired that he’s able to repeat it, but, from a doctor’s perspective, he shouldn’t be able to do it. I think that, medically, he’s kind of a surprise. He shouldn’t be able to do it, but he is doing it. What does that mean? That means that maybe he’s contributed something to the study of this disease, and we know that music does have this magical quality. It’s been therapeutic in various ways in the autistic community and now we know it’s therapeutic. We’ve always known that it was therapeutic. We just didn’t know that it could actually be used as a medicine. What we’re finding out, and it’s the tip of the iceberg, is music as medicine. That is a new concept and it could be fantastic if we actually find out that music is therapeutic - that Alzheimer’s patients that sing and participate in something like a choir, where they sing together regularly, every day or every other day – and in which there is some kind of organized behaviour, in that group, compared to another group – we may find that the disease hasn’t progressed that rapidly in the group that sings as in the group that doesn’t sing. Well, then you’re on to something. You know? Because then, maybe, you have a tool, something that can blossom in ways that we never even imagined. Maybe we have something that can someday be used to, at least, alleviate some of the symptoms of the disease, even if you just make sure that music remains a part of the Alzheimer’s patient’s life, and that music is always available and is played in the home; trying to get them to participate so it helps them remember things. It helps them keep in touch and feel more a part of what’s going on, which is one of the most important things going on in the Glen Campbell saga. It’s a public airing of something that usually occurs privately behind closed doors. So, in a way, it’s testing the waters; what kind of appetite does the public have for this sort of thing? But the truth is that it should be brought out and aired out more, and it’s tragic the way that Alzheimer’s patients are shut away into little cell-like rooms and institutions where they gradually lose their memories of their whole lives. There must be something else that can be done. PB: Jimmy, your mother was not around to see you become famous. Yet I’m guessing she instilled some qualities in you that shaped your life and possibly your career as an artist. JW: She was a musician. She played the accordion and sang with the family. We were always improvising specials for Sunday morning services. Of course, this was all spiritual music, church music. But in those days, family really rotated around a musical centre after dinner, especially on the holidays, but anytime, really, because there wasn’t a television blaring on in every home in America, especially not in ours. People find this hard to believe. After dinner we would sit down at the piano and we would sing. Now this seems like an absolutely fantastical idea, but this is what we did. It seems so quaint to me now that I can hardly believe that I’m saying it. We became pretty good at it, improvising harmonies and making up our own arrangements. It was good. It gave each member of the family an opportunity to try a new idea. “Why don’t we do this?” And anyone could contribute. It wasn’t a rigid scenario. It was democracy. True musical democracy, which I carried into my professional life as a musician effortlessly – oh, this is what I do. I’ve already been taught to do this. A lot of people with very classical musical educations have a lot of trouble transitioning into the music business just because of that because they don’t know how to, we call it, “woodshed.” And it’s just letting everybody contribute, and then sort of seeing what happens. That seems to be sometimes one of the hardest things to do – to just let go and let the music seek its own level, which it will do. I’ve said before that every song knows what it wants to do. If you can just get out of the way, it can write itself. My mother was the guiding light as far as music was concerned. I took lessons from the age of six. She enforced those lessons. It was not optional behaviour. There was real punishment if the practicing wasn’t done. There was some teeth behind it. It was something that meant enough to her to actually hold our feet to the fire. Some of my other brothers and sisters weren’t as musical. My brother was a fantastic athlete and eventually went to a major college on a basketball scholarship. So after a while, he was allowed to stop playing the piano (Laughs). But I was never allowed to stop. When I was twelve years old, I became church pianist. It was four short years after that that she passed away and she was only 36 years old. I hadn’t graduated high school, so she never saw any of that ballyhoo. She just never saw any of it. I don’t know how she would have reacted to it. I think she would have been pretty confused by some of my behaviour, probably quite upset. I think she would have cared less about the fame and fortune aspect and notoriety of songs in the public perception; well, this great, young kid is a songwriter, as really an old, traditional songwriter, and a great one, which seemed to be the sort of theme of my career. She would have cared less about that “theme of my career”, than that I wasn’t playing in church anymore. I think that would have been devastating to her. So if my mother had lived, it would have changed my life a lot. I’m certain that if I had become involved in music, I would have had to stay in church, because I wouldn’t have been able to withstand her – she would have been too strong for me. I couldn’t have left the church the way I did, and who knows? Maybe that would have been a better thing for me. Much of my younger years as a wunderkind were sort of rocky and full of quite objectionable things. PB: Jimmy, your songwriting has been compared to that of Cole Porter and George Gershwin. Were they inspirations? JW: I’m not sure where the Cole Porter influence comes from because he was so much better educated than I was. I never had the education to be as smooth and sophisticated as Cole Porter, although it’s certainly a nice compliment. In the case of George Gershwin, I certainly am a chordalist. I love Stravinsky, Copeland, and Benjamin Britten. All the great chordal composers are my favourites. For me, music without a chordal sense is just another noise. I don’t think you can be an American composer and not be influenced by George Gershwin. First of all, by the songs which were so tuneful and memorable and heart wrenching and touching, but secondly, by the classical music, which gave us all hope, however faint, that one day we might be able to move on to a whole other level of music, as well. He allowed his classical muse to influence his pop music writing and vice versa and I feel that there is a marked similarity in us – in the sense that I feel exactly the same way about classical music and rock music. I can’t separate them. It’s either really good or it’s not very good. Part of being really good is to have a strong, inventive, original chord structure at the very centre of a composition, even if it’s just a pop song. I really believe that. I teach that. I’m on record in my book, ‘Tunesmith’, as saying that one of the elements of a really, important song is this chord structure, that Gershwin always believed in strongly, and it was a characteristic of his music that was almost overpowering. PB: Thank you, Jimmy.

Band Links:-

https://www.jimmywebb.com/https://www.facebook.com/JimmyWebbMusic

https://twitter.com/realjimmywebb

Picture Gallery:-

Visitor Comments:- |

| 521 Posted By: lisa , chicago, il. on 02 Feb 2012 |

|

It is great to hear from so many of Jimmy's loyal fans out there.

I agree that meeting Jimmy after the show is a fantastic experience, and that he will enjoy the encounter just as much as you will.

Thanks for the heartfelt responses!

Lisa Torem

|

| 520 Posted By: Sandra Carr Neely, Columbia, Missouri on 02 Feb 2012 |

|

I am going to see Jimmy Webb (my husband's going too!) in K.C. next week at a place called Knuckelheads!His music is genious.I think of his songs as a soundtrack for my early 20's! So we are listening to one of his CDs and I said that I wished he would go on tour.I barely finished the sentence before I flew to the computer and typed in Jimmy Webb 2012 dates!There it was! So I call Knuclelhead's & order 2 tickets. Now here's the kicker.

I do not have any tickets to show when we arrive! My name is on "the list" at the door! I even paid for assigned seating!When I read that he may talk to the fans after the concert my head started spinning!Oh! I don't have a clue as to where Knuckelhead's is in K. C.We do have a one of those deals where you type in where you want to go and it guides you there. Of course I will have to listen to my husband argue with it!I will be hopefully very close and be the one crying the moment he hits the first note on Galveston& Worst That Could Happen. Reading your interview just made me love Jimmy and his music even more. (if possible) I also love that he is called Jimmy! I am counting the days! Thanks for you interview and thank you, Jimmy in advance!

|

| 518 Posted By: Chris Killingsworth, Silicon Valley, CA, USA on 02 Feb 2012 |

|

OK, that sounds a little grandiose [inside reference] but I have acquired a great appreciation not only for his talent but his humanity and nature. I attended a performance last year and was blown away, and meeting him after the show was so nice. I would just say, if you get the chance, see him in concert, esp small venues. Cheers!

|

| 517 Posted By: Jim Basler, Dallas, TX on 02 Feb 2012 |

|

I enjoyed this interview very much. Thanks for making it available

|

interviews |

|

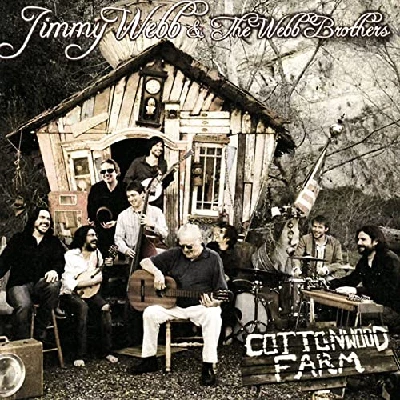

Interview (2009) |

|

| American songwriter Jimmy Webb has written songs such as 'Galveston', 'By The Time I Get to Phoenix', 'Wichita Lineman' and 'MacArthur Park'. He speaks to Lisa Torem about his long musical career and 'Cottonwood Farm'. the album he has recorded with his sons, the Webb Brothers |

live reviews |

|

(With support from Ashley Campbell and Thor Jenson), Cadogan Hall, London. 27/5/2022 |

|

| Dastardly watches a captivating performance by Jimmy Webb proving he’s as skilled a raconteur as he is songsmith. |

| Old Town School, Chicago, 20/1/2012 |

| Queens Hall, Edinburgh, 6/11/2009 |

features |

|

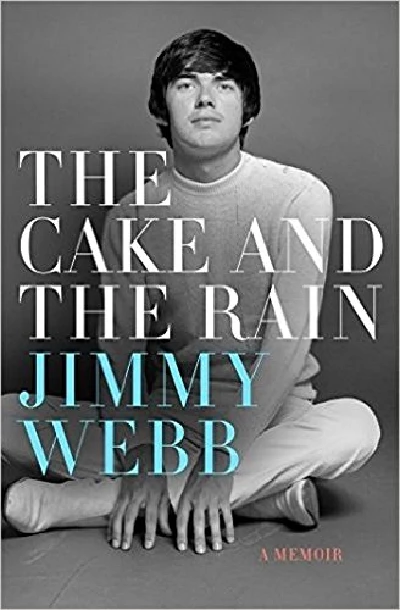

Raging Pages (2022) |

|

| In her ‘Raging Pages’ book column Lisa Torem examines Jimmy Webb’s 2017 memoir ‘The Cake and the Rain'. |

reviews |

|

Cottonwood Farm (2009) |

|

| Fabulous and inpsirational album which finds much legendary American singer-songwriter Jimmy Webb, collaborating with his four sons, the Webb Brothers, and also Bob Webb, his father |

most viewed articles

current edition

John McKay - InterviewCathode Ray - Interview

Robert Forster - Interview

When Rivers Meet - Waterfront, Norwich, 29/5/2025

Spear Of Destiny - Interview

Fiona Hutchings - Interview

Carl Ewens - David Bowie 1964 to 1982 On Track: Every Album, Every Song

Chris Wade - Interview

Shrag - Huw Stephens Session 08.12.10 and Marc Riley Session 21.03.12

Brian Wilson - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

previous editions

Heavenly - P.U.N.K. Girl EPBoomtown Rats - Ten Songs That Made Me Love....

Manic Street Preachers - (Gig of a Lifetime) Millennium Stadium, Cardiff, December 1999

Allan Clarke - Interview

Oasis - Oasis, Earl's Court, London, 1995

Barrie Barlow - Interview

Beautiful South - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

Pixies - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

Chuck Prophet - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

Dwina Gibb - Interview

most viewed reviews

current edition

Peter Doolan - I Am a Tree Rooted to the Spot and a Snake Moves Around Me,in a CircleVinny Peculiar - Things Too Long Left Unsaid

Garbage - Let All That We Imagine Be The Light

Vultures - Liz Kershaw Session 16.06.88

John McKay - Sixes and #Sevens

Little Simz - Lotus

HAIM - I Quit

Pulp - More

Lapsley - I'm a Hurricane, I'm a Woman In Love

Billy Nomates - Metalhorse

Pennyblackmusic Regular Contributors

Adrian Janes

Amanda J. Window

Andrew Twambley

Anthony Dhanendran

Benjamin Howarth

Cila Warncke

Daniel Cressey

Darren Aston

Dastardly

Dave Goodwin

Denzil Watson

Dominic B. Simpson

Eoghan Lyng

Fiona Hutchings

Harry Sherriff

Helen Tipping

Jamie Rowland

John Clarkson

Julie Cruickshank

Kimberly Bright

Lisa Torem

Maarten Schiethart