Eric Burdon - Interview

by Lisa Torem

published: 29 / 7 / 2010

intro

Eric Burdon, the front man with influential 60's blues group the Animals, talks to Lisa Torem about his band's career and legacy

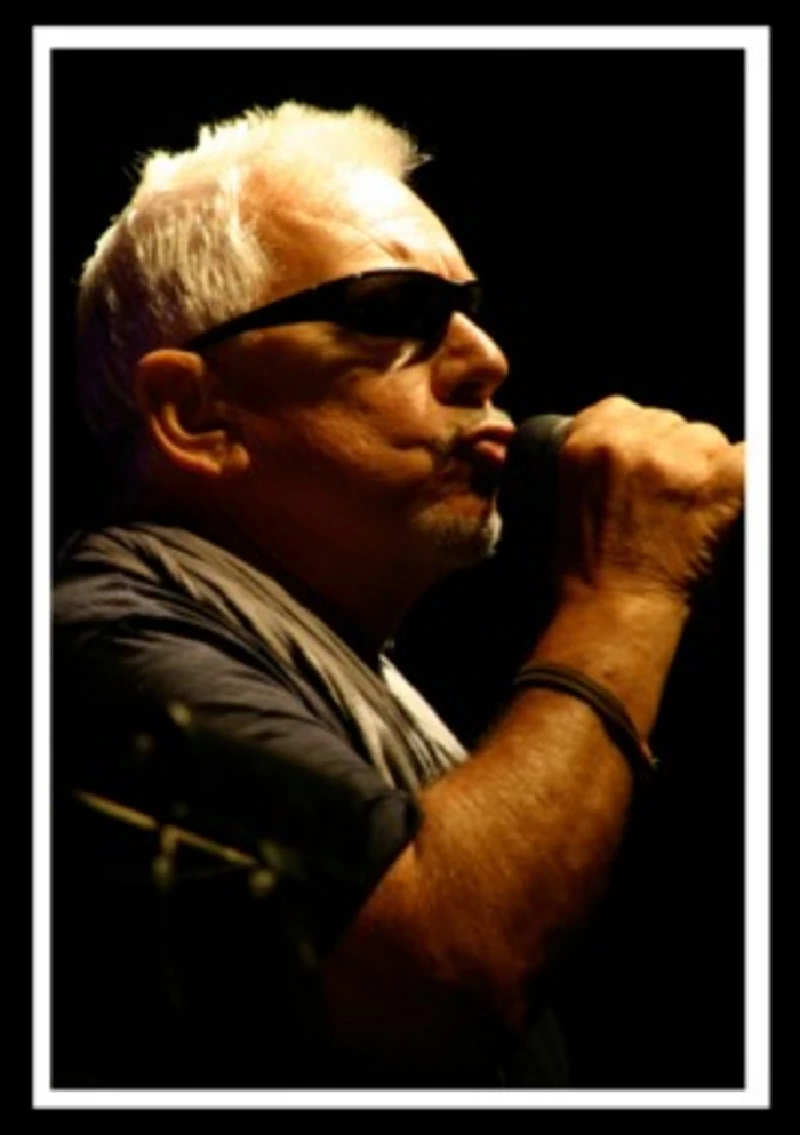

Eric Burdon, the singer with the irresistibly scratchy, but profoundly emotional voice and irreverent charm, was as vital to the British Invasion as he later became to the San Francisco era of psychedelia. In the 1970s, as the front man in the funk percussive group, War, Burdon experimented with that spoken-word soliloquy, 'Spill the Wine', in a performance style that was unarguably ahead of its time. Burdon has also enjoyed a career in film. Credits include scoring and acting in Christel Bushmann's movie 'Comeback', acting in 'Gibbi West Germany', 'The Doors', 'My Brother and I' by Antonis Kokkinos and Thorsten Schmidt's 'Snow Fall on New Year's Eve'. In addition, Burdon has played a strong role in producing 'Joe Versus the Volcano', 'Hamburger Hill', 'Casino' and 'Boogie Nights'. Born in Newcastle, England, the young singer was fascinated by John Lee Hooker, Chuck Berry and Ray Charles. Radio Caroline, the British pirate radio station, latched on to the raw energy his band, the Animals, exemplified and made them the subject of their first US broadcast. Burdon has always taken risks and has much to show for, career-wise, as a result of that ability. 'The House of the Rising Sun' was a traditional folk song, with simple chords and tragic lyrics, until Burdon brought its intensity up several notches further with the Animals' electric version which soared up the international charts in 1964, making the lads immediate icons. When Eric and the Animals ultimately took off in different directions after several albums and over twenty singles, Burdon went solo and landed in 1967 at the popular Monterey Pop Festival, where he honoured that event in song and blasted his own psychedelic version of 'Paint it Black' and 'Gin House Blues' to throngs of admirers. His anti-war song, 'Sky Pilot' exemplified, for many of the American youth, the travesty of the Vietnam conflict. Harpist Lee Oskar and Burdon formed the funky percussive Eric Burdon and War which featured the singer's intense, smoky interpretations of 'Tobacco Road' and 'Spill the Wine.' The two LPs, 'The Black Man's Burdon'(1970) and 'Love Is All Around'(1976) paid tribute to that collaboration. Burdon went on, also, to collaborate with bluesy Jimmy Witherspoon on the 1971 album, 'Guilty'. Ike White and The San Quentin Prison Band also joined forces. In 1977 the original Animals recorded 'Before We Were so Rudely Interrupted'. They also reunited in 1983 for 'Ark' and the final reunion sparked the live 'Rip It to Shreds!' album. Burdon authored 'I Used to Be an Animal, But I'm All Right Now' in 1986 and the sequel 'Don't Let Me Be Misunderstood' which was published in 2000. In these memoirs, Burdon chronicles his relationships with famous friends such as Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin and John Lennon, through bittersweet and humourous anecdotes. 2004 was the year that Burdon's solo studio album, 'My Secret Life', produced by Grammy winner, Tony Braunagel, came about, and a year later, with Pete York, on drums and Christoph Steinbach, on keyboards, he formed a boogie-woogie band, the Blue Knights. In 2006 he released his most recent studio album,'Soul of a Man'. Currently touring with Eric McFadden(guitar), Paul Rourke(bass), Red Young (keyboards) and Tony Braunagel(drums) in a new line-up of the Animals, Burdon is reclaiming the cultural throne as one of the most skilled, versatile and dynamic performers ever to grace the stage. That said, defying authority through music and personal conviction, appears to be part of Burdon's legacy. In conversation with Pennyblackmusic, he shares some historical insights and reflects on his career. PB: Eric, when did you first realize that your voice moved others? Also, during your formative years in Newcastle, what kind of music were you exposed to? EB: I first realized that my voice moved me when my mother would move me out of the shower. As a kid, I used to sing in the shower, imitating Johnny Ray. The acoustics in the bathroom made my voice echo and my mother would yell, “Get out of the shower! You’re taking up too much time and making too much noise!” That was when I first realized that my voice moved people. It moved me out of the bathroom and into the air raid shelter down in the garden which soon became a garage. That was the beginning of the evolution of the garage band. It was lots of fun. PB: Do you have siblings or were there any musical mentors in the family? EB: Yes, I have a sister Irene, three years younger than me. In later years she surprised me by joining a sort of choir or glee club in Tyneside. So I guess she did have a kind of a talent, but, most importantly, she did have the courage to step up to the plate and try out. PB: When the Animals were managed by Mickey Most, who also managed Herman’s Hermits, how much of the band’s image did he create? Did the Animals rough teddy-boy image come about because of your actual living conditions, in a working class environment in Newcastle, or was the image encouraged as a way to contrast the image of the poppier Peter Noone? EB: Mickey Most didn’t manage the Animals. He was an aspiring record producer and he had been a pop star down in South Africa. Most had started collecting groups that he could produce and Herman's Hermits were a perfect group for him, but we weren't teddy-boys. We did emerge from the living conditions of the working class. The environment in Newcastle was that of the birth place of the industrial revolution. From the back door of my house I could see the cranes along the River Tyne and they always looked like prehistoric monsters to me. Peter Noone, I assume, was part of a middle class family and he was a very nice boy. He projected that nice boy image and he was perfect for Mickey. He worked hard, his fans loved him and he loved his fans. PB: The early years cost you some financial and emotional heartache. Alan Price, the keyboard player, of your original line-up, managed to obtain royalties for 'The House of the Rising Sun' simply because only one band member’s name could fit on the record. Being young, talented musicians, you were thrust into a world of business that must have been daunting at times. What did you learn about the music business from those early days and do you feel the emerging artists coming up today have to face similar obstacles? EB: When the band was still the original Animals, we were from Newcastle and we were proud of it. We had a great time at the shows, but when it came to business, we kind of rejected it except for Alan Price who had been an accountant. He knew about all of the financial things that we didn’t understand or (at the time) didn't care about to be honest with you. Alan knew a lot about money and he wasn’t going to tell the rest of us. By just keeping quiet, Price was able to walk away with the lion’s share of the royalties for 'House of the Rising Sun,' but there’s no use crying over spilled milk. PB: In August of 1965, ‘We’ve Got to Get Out of This Place’ reached number 2 on the UK pop singles chart, second to the Beatles 'Help.' What was your relationship like with the Beatles, considering your repertoire was so much darker and rootsier at that time? EB: There's no way that the Animals are darker than the Beatles. Just check out their 'Rubber Soul' album and onwards. You'll see what dark is. Where their lives went because they were the Beatles, nobody would wish on their greatest enemy. It's no wonder that they wanted to break up and it's no wonder that John Lennon got angry. I can understand John Lennon very well because he and I had a lot in common. We were both born in 1941, we were both from northern cities in England and we both detested authority. PB: There were two versions of 'We've Got to Get Out of This Place,' one for the UK and one for the US, but one recorded for the UK remained the one more valued by recording professionals. At one point, this version found its way into the US, but die-hard fans wanted no part of it. They had already become accustomed to their own version. Do you have any comments about that? EB: I don't know what you're talking about with 'We've Got to Get Out of This Place.' 'House of the Rising Sun' was the big one and our music was hacked to pieces by the US editors. They were all for cutting the songs down to as short a time as possible so that they could put their commercials in there and make all their money. Because of the edits, even the cover bands were playing the edited version of the song. PB: A group called High Numbers witnessed you stomping on a piano with your cowboy boots at a club in the 60s. This band later became the Who. Were they highly influenced by your maverick approach to performance? EB: There was a big white grand piano on the stage that was always out of tune. It was in the way of our drum kit and we couldn’t perform, so it deserved to be destroyed. I got up on top of it and started stomping on it, then my band joined me and then the audience joined in as well. Everybody had a great time. Whether the High Numbers were in the audience, I don’t know. It makes a great story though, doesn’t it? PB: Definitely. Some of the early hits were written by New York writers Barry Mann and Cynthia Weil. ‘We’ve Got to Get Out of This Place’ almost got recorded by the Righteous Brothers, but you believed the song would be a hit, though Most was luke-warm towards the idea of recording it at first. The opening lyric is, “In this dirty old part of the city, where the sun refuses to shine…” and the bass line created by Chas Chandler helped to create a dark, gritty urban feel. The song turned out to be a great vehicle for your bluesy style. How did you know it would take off? EB: You said that people were mostly “luke-warm” towards it, but I’ve never seen anybody’s reaction to it be only luke-warm, at least now when I’m singing it live on stage. You know, it's the beginning of 'We’ve Got to Get Out of This Place' that makes it felt. It is a perfect song to sing. It’s a great song to change and express anything relevant to the current times. I remember Cynthia Weil turning to me, while we were sitting in a doctor's office, in Beverly Hills and saying, “You know, I always hated what you did to our song.” And all I said back to her was, “Yeah? Well, sorry…” She said that they got used to it, but I don’t really believe that. PB: I was referring to Most not having the faith in the song that you did. But, I agree with you that it's a great song. Another song called ‘The Rising Sun Blues’ was sung by a miner’s daughter and field-recorded by musicologist Alan Lomax. This song foreshadowed ‘House of the Rising Sun’ which had been previously recorded by Josh White in 1944 and 1949, Nina Simone in 1962 and even Bob Dylan, also in the early 60s. Your cover was so highly acclaimed, however, that Dylan was accused of plagiarism. Have those wounds healed? EB: I don’t know. I’d have to ask myself who was wounded in the first place? Not me. I think that Bob just had to make some adjustments. I’m not sure there were any wounds that needed to be healed. PB: You first heard ‘The House of the Rising Sun’ when folk-singer Johnny Handle performed it in Newcastle. Could you imagine yourself singing that song with the Animals, or recording it, at that time? EB: The Animals didn’t exist at that time. Not for another 4 years. PB: ‘We’ve Got To Get Out of This Place’ has been covered by acts as diverse as Ann Wilson, the Partridge Family, Jello Biafra, DOA, Mariannne Faithfull, David Johansen, Blue Oyster Cult and Grand Funk Railroad. Most of these versions are much more produced and syncopated than the one recorded and made famous by the Animals.What made your interpretation unique and why do you think these covers conveyed such a different sound? EB: I think it’s a case of over acting while singing the song. PB: Are you surprised that so many acts have chosen to cover this song? Do you feel that the heart of the song has suffered due to overproduction? EB: No, I’m not surprised and I haven’t heard all of the versions so I don’t know if the heart of the song suffered. PB: The US Armed Forces used ‘We’ve Got to Get Out of This Place’ as an anthem, as well, and Michael Moore’s 'Fahrenheit 911' also got on the bandwagon. Did you envision a political ideology that related to these lyrics? EB: It was about getting out of my home town and getting to go to all the places I’ve been since. About a political ideology, yeah. Everything is a conspiracy and nothing happens by accident. I do wish that the US armed forces would get out of that place and come back to where they belong. Michael Moore, though, used the Barry Mann/Cynthia Weil version, not The Animals. version PB: I'm surprised to hear that Moore used that other version. You’ve written not one, but two memoirs, 'I Used to Be an Animal but I’m All Right Now', which was followed by 'Don’t Let Me Be Misunderstood' about a decade and a half later.Were you intending to follow up that first memoir initially or were you just motivated later in your career to share more about your personal experiences and career? EB: I wrote two books in an attempt to put down what happened, the way it happened before I forget and before people get too offended. I don't think of myself as an author. Maybe I could be an author if I had the time, the space and the inspiration and if I could get away from rock and roll, but you can't get away from it. PB: No, I'm sure you can't. In 2006, you returned to your blues roots and released 'Soul of a Man' including 'The Red Cross Store'. We know that blues means a great deal to you, but of all the great material out there what made you select these particular tracks? EB: I never left my blues roots. I selected those tracks because we wanted to be in touch with the disaster that was happening in Louisiana and New Orleans, in particular. Katrina was a disaster, and the lack of response was even worse. Unless you've experienced it, you don't know the meaning of "I won't go back to the Red Cross store no more." PB: You were said to have been the first rocker to have played behind the Iron Curtain. What do you recall from that performance experience? EB: Yes, we were the first people to record behind the Iron Curtain. I remember from that that Communism sucks. Those people were starving. Also, I remember that body heat was the call of the day. There was no heating at the venues and it was 30 degrees below zero. We were all wearing fur coats and gloves. I’m really looking forward to going back soon. PB: Looking back, was it the right emotional and artistic decision to leave the UK and move to California? EB: Looking back, it wasn't an emotional or artistic decision. It was about life and death. I came to California because I can breathe better out here in the dry air. There are other reasons as well, but that’s one of them. PB: What stylistic changes have you made on your current world tour as opposed to other touring commitments? EB: What we do is select songs according to and depending on, the country that we have previously been in, whether it was just last year or three years go. PB: Eric, what has been the most important advice you have ever received? Also, why do you think you have survived this career when so many close friends had succumbed to drugs and other temptations? EB: I succumbed to drugs for a long time, but I climbed out of it. You can’t be doing that all your life and most people shouldn’t be doing it any part of their life. But, truth is truth and some of my friends are gone. I don’t worry about it. It doesn’t affect me personally. PB: What would be on your list of five favourite songs ever written? EB: I’m a singer, but I’m not a computer. I can’t say what my five favorite songs ever written are. A new one comes around every six months or so. PB: Who, then, are your favorite songwriters? EB: Memphis Slim, Chuck Berry, Leonard Cohen, my uncle George, Marvin Gaye, Bo Diddley, Lennon and McCartney PB: If you could have been born in any other era, which one would have been most intriguing? EB: Definitely California in the 1920s or 1930s PB: Thank you, Eric. More information can be found on www.ericburdon.com. The photographs that accompany this article were taken by Marianna Proustou.

Band Links:-

http://www.ericburdon.com/https://www.facebook.com/OfficialEricBurdon

https://twitter.com/ericburdon

Picture Gallery:-

Visitor Comments:- |

| 449 Posted By: Diane Crane, Greenfield,Mass. USA on 05 Jul 2011 |

|

I can't help but compare you to my boyfriend who last appeared at the IRON HORSE in Northampton, Ma. Your'e one of the greats, but you know that. CLEAN LIVING was my boyfriend's group; he was the frontman. People used to call him "The Enforcer" cause if any tough gave the band trouble he'd come down off the stage and gently persuade, or whip, chop or puree, as called for. Norman and the boys were great talents, but they NEVER TOURED!!! At this time Norm isn't in great health. Bless you, Eric.

|

| 345 Posted By: Myshkin, London, UK on 30 Aug 2010 |

|

Great article, Lisa. Lots of info, detail and just an easily readable, enjoyable piece. Love it.

|

interviews |

|

Interview (2016) |

|

| 60's icon and Animals front man Eric Burdon speaks with Lisa Torem about performing, improvising and the influence of his Newcastle upbringing |

| Interview (2013) |

live reviews |

|

Festival Park, Elgin, Illinois, 24/8/2013 |

| Lisa Torem watches 60's blues veteran Eric Burdon with a new line-up of the Animals play a tight set of classic and new material at Festival Park in Elgin, Illinois |

| Naperville Rib Fest, Naperville, 3/7/2010 |

most viewed articles

current edition

Carl Ewens - David Bowie 1964 to 1982 On Track: Every Album, Every SongArmory Show - Interview with Richard Jobson

Colin Blunstone - Thalia Hall, Chicago, 16/7/2025

Bathers - Photoscapes 1

Visor Fest - Valencia, Spain, 26/9/2025...27/9/2025

John McKay - Interview

Billie Eilish - O2 Arena, London, 10/7/2025

Robert Forster - Interview

Sir Tim Rice - Interview

Loft - Interview

previous editions

Heavenly - P.U.N.K. Girl EPManic Street Preachers - (Gig of a Lifetime) Millennium Stadium, Cardiff, December 1999

Beautiful South - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

Oasis - Oasis, Earl's Court, London, 1995

Pixies - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

Trudie Myerscough-Harris - Interview

Doris Brendel - Interview

Prolapse - Interview

Simon Heavisides - Destiny Stopped Screaming: The Life and Times of Adrian Borland

Paul Clerehugh - Interview

most viewed reviews

current edition

Sick Man of Europe - The Sick Man of EuropeLucy Spraggan - Other Sides of the Moon

Amy Macdonald - Is This What You've Been Waiting For?

Phew, Erika Kobayashi,, Dieter Moebius - Radium Girls

Davey Woodward - Mumbo in the Jumbo

Blueboy - 2

Bush - I Beat Loneliness

Alice Cooper - The Revenge of Alice Cooper

Cynthia Erivo - I Forgive You

Suzanne Vega - Flying With Angels

Pennyblackmusic Regular Contributors

Adrian Janes

Amanda J. Window

Andrew Twambley

Anthony Dhanendran

Benjamin Howarth

Cila Warncke

Daniel Cressey

Darren Aston

Dastardly

Dave Goodwin

Denzil Watson

Dominic B. Simpson

Eoghan Lyng

Fiona Hutchings

Harry Sherriff

Helen Tipping

Jamie Rowland

John Clarkson

Julie Cruickshank

Kimberly Bright

Lisa Torem

Maarten Schiethart