Willard Grant Conspiracy - Interview

by John Clarkson

published: 22 / 3 / 2008

intro

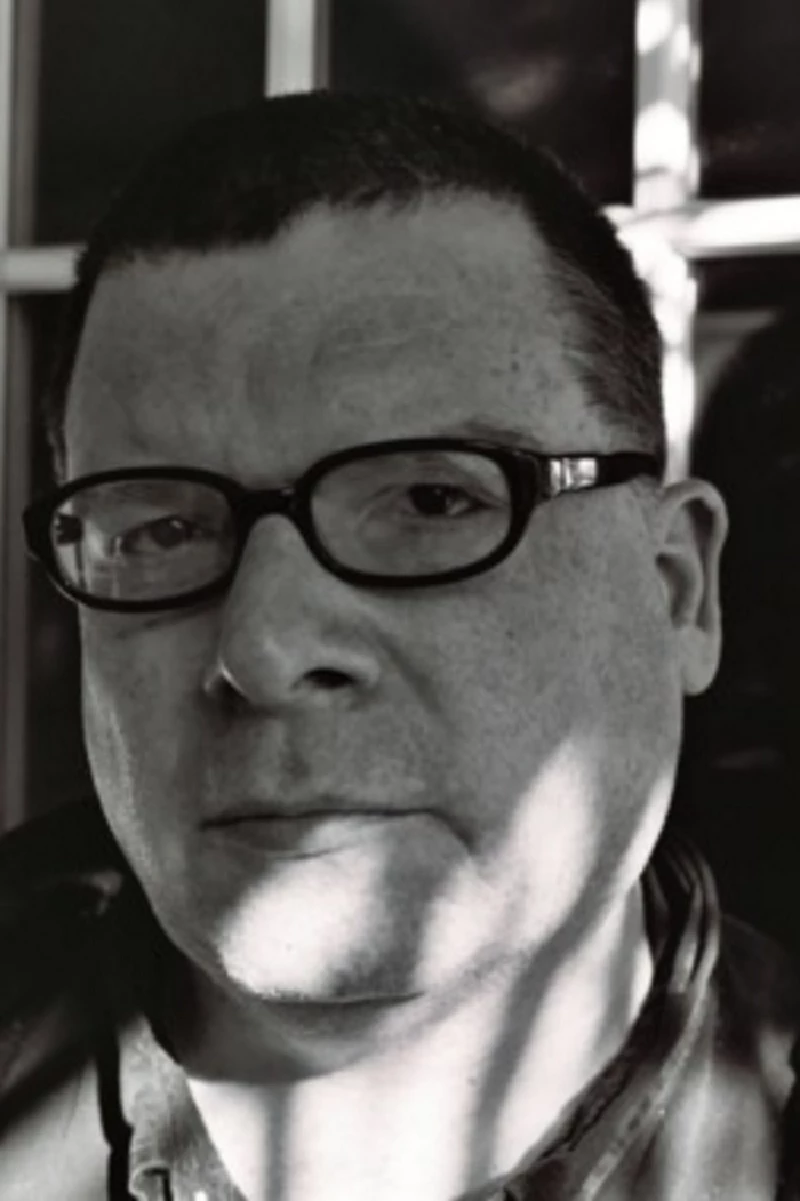

The Willard Grant Conspiracy's latest album, 'Pilgrim Road', has found singer Robert Fisher's collective working with Scottish composer and orchestral arranger Malcolm Lindsay. He speaks to John Clarkson about the collaboration and the new album

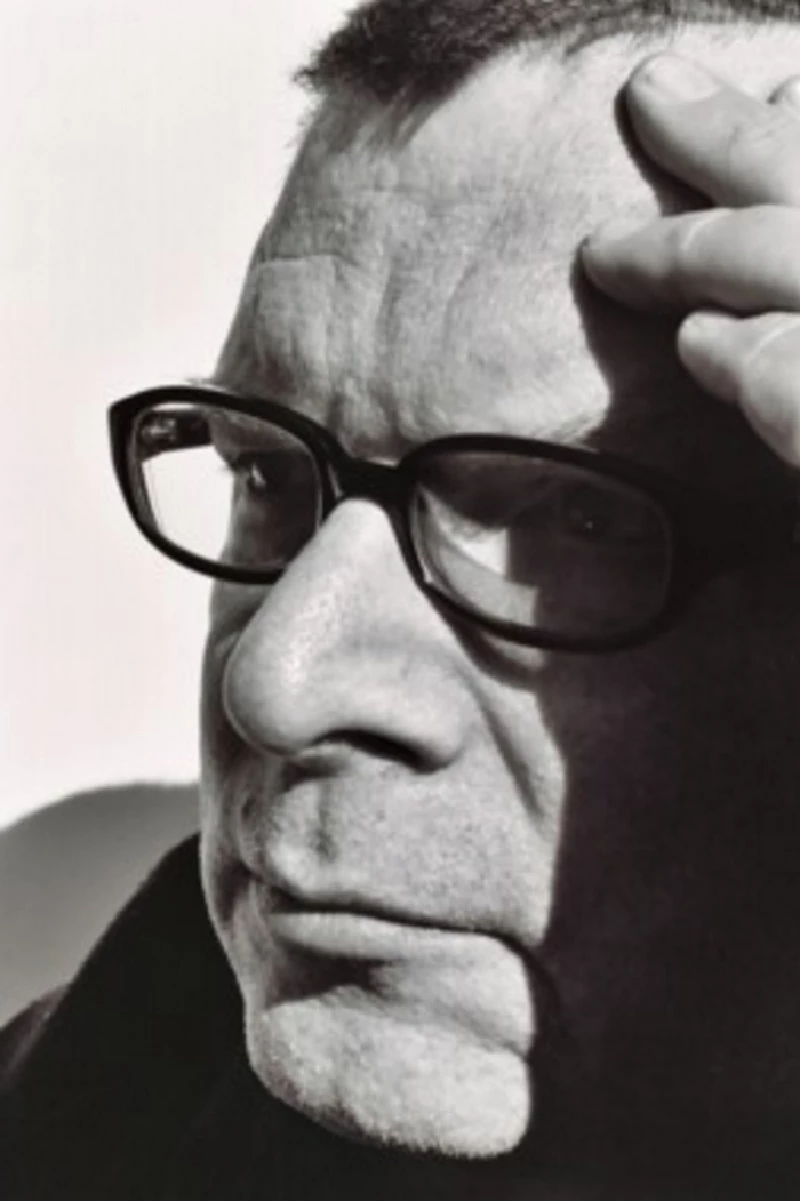

It is the tail end of 2000, a wet night in early December, and the Willard Grant Conspiracy are nearing the conclusion of a fifty date European tour which has taken them over the last two months across most of the countries in central Europe and into several of its eastern blocks including the Czech Republic and Slovenia. Singer Robert Fisher’s ever mutating collective is up to seven in number for this tour. Guitarist Paul Austin, Fisher’s co-writer on the Willard Grant Conspiracy’s first three albums, ‘3AM Sunday at Fortune Otto’s’ (1997), ‘Flying Low’ (1998), ‘Mojave’ (1999) and also their current album, ‘Everything’s Fine’ (2000), is still a member of the band. Viola player David Michael Curry, who will in time become the longest-serving member of the group after Fisher, is there. It is also Japanese-born but Dutch-based keyboardist Yuko Murata’s first time on the road with the WGC, and that too of Newcastle-born second guitarist, Simon Alpin. Both will become mainstays of the group, Murata continuing to tour and record with the group until this day, and Alpin staying for the next four years. Tonight the Willard Grant Conspiracy are in Glasgow at the 13th Note, a scruffy cellar club, at the edge of the River Clyde. It’s the WGC’s third time in Glasgow, and third ever Scottish show. Both of the WGC’s previous visits to the city were triumphant affairs, highlights of their tours. Tonight, however, is not going well. It is Sunday night for a start, a traditionally dead time for those playing gigs, in which with money spent after the weekend, fewer people tend to venture out. Worse still, the 13th Note’s soundman has not turned up. With Fisher and Alpin both dashing back and forth between the stage and mixing desk, the WGC is forced eventually as a result to do its own sound check, a difficult task at the best of times, but with a seven piece group impossibly slow. Doors as a result open long after time to a disgruntled audience, and, after a brief set from support act Jess Klein, the band arrive on stage over an hour late. The group, fired up on frustration as much as anything else, manages against the odds to play a strong set. With much of the crowd having to leave long before the end to catch last buses or trains, the show has, however, been a shambles. Especially after the success of their previous Glaswegian shows, and in what has been otherwise a happy tour, it has been a miserable, bitterly disappointing night. Afterwards, as the 13th Note clears, Fisher stays behind at the merchandise desk talking to friends and fans, when he is approached by a man, with silvering hair and in his early 40's, who introduces himself as Malcolm Lindsay, a strings and orchestral arranger. Lindsay tells him that he has enjoyed the show, and says, if Fisher is interested, that he would like to work with him. “After that ?” quips Fisher astonished, wondering if he is joking. Lindsay has probably undersold himself. He is at that time one of Scotland’s most promising composers. A co-founder of Deacon Blue with whom he played between 1984 and 1986, and a member with Stuart Duffin of the Moors who released an album, ‘Moor Fire Burn’, in 1995, he has a background in rock. He, however, also has roots in jazz, and has as well written and seen performed dozens of classical pieces. He will go on to work and do vocal arrangements on the Delgadoes’ 2002 album, ‘Hate’ ; to compose as well the soundtrack for former Skids’ vocalist Richard Jobson’s 2003 directorial cinematic debut, ’16 Years of Alcohol’, and to help David Byrne, with string arrangements for his soundtrack for the Euan McGregor film, ‘Young Adam’, which will also be released in 2003. A lot will change over the coming years. Paul Austin will leave the WGC amicably the following summer, moving from the band’s then base in Boston to Seattle to be with the Walkabouts’ drummer, Terri Moeller, who played drums on that 2000 WGC tour. They will form a band there, the Transmissionary Six, and eventually get married. Fisher will also relocate, returning after being away for 23 years,to his native California in 2003. The WGC will also part company with Slow River, the record label which released its first four albums, and sign to Loose Music in Britain and Glitterhouse in Europe. It will release another two albums, a massively-acclaimed traditionally-influenced album of largely acoustic folk rock, ‘Regard the End’ (2003), and the blistering, psychedelic ‘Let It Roll’ (2005). There will be many other tours, with the WGC, as Fisher enjoys it, ever evolving, often having over 30 members on hand depending on who is available at any one time. The group will in slightly better circumstances even play the 13th Note again in 2005, which in the meantime has closed down and been resurrected as part of the Barfly chain. From this beginning, Robert Fisher and Malcolm Lindsay will keep in touch, talking together after other WGC shows in Glasgow and Edinburgh, and in a late night e-mail and phone correspondence. Finally, after they have tried out working together by writing a couple of songs with each other over the internet, Fisher will come to Scotland in October 2006, just before the start of a five week European tour, to work on an album and for an intensive 10 day period of writing and recording in Lindsay’s home studio in Glasgow. While the bulk of an album is sketched out during that period, he will return after the tour for a few more days, and then again in the summer of 2007. In a career that has taken him across seven studio albums with the Willard Grant Conspiracy from country to punk, blues to pop and folk to psychedelia, ‘Pilgrim Road’, the resulting album, which is being released on the 5th May, is possibly Fisher’s finest record to date. It is an album that manages to be both minimalistic and orchestral at the same time. Lindsay’s sparse, rippling chords of keyboards and piano and more occasional flutterings of acoustic and electric guitar are reminiscent in their atmospheric sparseness of the Blue Nile and serve as a backdrop to each of it ten tracks. 'Pilgrim Road' also features contributions from several WGC regulars of previous albums including Josh Hillman (violin and viola) ; Dennis Cronin (trumpet) ; the Walkabouts’ Chris Eckman (persophone) ; Erik Van Loo (double bass), Tom King (percussion) and David Michael Curry (viola and singing saw) as well as various members of the Scottish music community such as the Doghouse Roses’ Iona MacDonald (vocals) and Paul Tasker (slide guitar), Stuart Duffin, who, a professional artist, has also contributed the album’s artwork (electric upright bass and church bells), and Rachel Morley (vocals). Rather than mashing this instrumentation together, each instrument is, however, allowed to breathe, drifting in and out of the mix across Lindsay’s evocative arrangements, and creating a sound that is as subtle as it is sometimes flourishingly dramatic. Fisher was raised a Baptist, and, while no longer practising, remains a spiritual man. The second track on the album, ‘The Great Deceiver’, which is reprised at the end, finds him questioning and doubting his belief in God . Merging Paul Tasker and Malcolm Lindsay's spare licks of acoustic guitar and hums of organ with a duet between Fisher and Iona MacDonald, it also features a gospel-style choir. Other highlights include brooding opener, ‘Lost Hours’ ; covers of both the American Music Club’s ‘Miracle on 8th Street’ and Lal Waterson’s ‘Phoebe’, and an abstract jazz pop number, ‘Painter Blue’. With the Willard Grant Conspiracy about to go out on the road for a twelve date European tour in an eleven piece version which Robert Fisher has dubbed ‘The Pilgrim Road Orchestra’, Pennyblackmusic spoke to him, in what is our sixth interview with him, about the new record. PB : Your original working title for the album was ‘The Lost Hours’. At what point did it change its name to ‘Pilgrim Road’ ? RF : (Laughs)It actually went through a number of titles before it arrived at ‘Pilgrim Road’. ‘The Lost Hours’ was a working title because there is a song entitled that on the record. I also liked the notion of there being this hideaway at Malcolm’s home studio in Glasgow where we just worked away at this thing and the hours just disappeared. Later on it went through several other titles before ultimately ending up being ‘Pilgrim Road’. Every time I changed the title I found that someone else had the title that I had chosen. After falling on ‘Pilgrim Road’ I discovered that there are some similar titles to that as well, but having going through five or six titles (Laughs), I thought, “I am just going to go with this one and to let the chips fall where they may.” PB : What were some of those other titles ? RF : One of them was ‘Cautionary Tales’. I thought that was a nice one, but it turned out that Christopher Rees from Wales had released a record recently called that, so that didn’t work. There were a few others as well, but ‘Pilgrim Road’ was the one I eventually settled on. PB : Why did you go for that ? RF : Records tell you what they are as they happen. When we looked at the subject matter of what was going on the record, a lot of the songs told of these little mini-journeys and we realised that, as a whole, the album dealt with this whole notion of life being a pilgrimage during which you go through some level of enlightenment about who you are and why you are there and what you are doing there. It just seemed to fit really well. Malcolm and I talked about it afterwards, and realised that ‘Pilgrim Road’ is also an unconscious marriage of our influences. A couple of songs on there, for example, are a mash up of both Scottish and American sort of religious music. That was an interesting idea as well, this whole idea of the history of music being this handed down thing. The pilgrimage motion comes in to play there too because as songwriters and artists we all come with cap in hand looking for something that helps us move forward. You can end up on a journey in music in which you look at the art of it to understand your role as a songwriter and a collaborator and your relationship within it. If you choose music as your life’s work you’re never going to be bored (Laughs). Whether you’re writing about it or making or just listening to it as a fan, of which I do at least two of those three, there’s never going to be a time when you’re going to say I am bored. What an incredible luxury that is to be able to say that about anything ! The same is true about being a fan of good fiction or art of any kind. There is so much of a body of work there that when I hear people say, “I am bored with what is going on in my life”, I think to myself, “Well, geez, I am really grateful I am not.” There is always something new with music. Sometimes there is something old that is new. Sometimes it is something that you have overlooked when you were younger. Sometimes it is just a genre that you weren’t mature enough to appreciate. PB : On your early albums you had Paul Austin as your main collaborator and co-writer. Then, while you worked with a lot of other musicians on your next albums, you tended to write more on your own. Now on this album you have worked with Malcolm. Do you feel more comfortable when you are working with a main collaborator or is it something which doesn’t bother you ? RF : I hadn’t actually thought about it before until now (Laughs). The notion of working on my own doesn’t really register with me because I see working with the band, whatever the band may be at that time, as a collaboration. For me it is always about what seems like an interesting idea , rather than that thought of, “Okay, on this one I am going to collaborate with somebody”. ‘Pilgrim Road’ is a little different because the record had such a long gestation process. We actually began to work on songs on it, before ‘Let It Roll’, so in that regard I really did make a decision that I wanted to work with Malcolm specifically. I thought that it would be an interesting experience to push myself in areas that I wouldn’t normally go in because Malcolm’s background is so different to my own. His discipline in orchestral work was something that I don’t have a grasp on. I have a slightly better grasp now, but still don’t really, so I knew that working with him was really going to pay off in dividends. I had no idea what those dividends were going to be, but launching yourself into the unknown is usually a good idea, and so that was the thought behind that. PB : It is an album that is as minimalistic as much as it is orchestral . Did you always intend the album to be a minimalistic record ? RF : There were a couple of really significant things that I wanted to accomplish with this record. The first and most important thing was that the orchestral elements had to be involved as an organic part of the song writing. When Malcolm first suggested working together, my very first gut reaction was that, while I loved the idea, I didn’t want to do what a lot of bands do which is write a song and then get an arranger to come in and stick an orchestra up the arse of the song. When that happens, the orchestra usually sounds like a pad, which is of course what it is. I had no interest in doing that whatsoever, We have always used strings and horns as part of what we do anyway, and things like piano as well, so it just seemed to me that if we were going to use these different elements it should be very much in the way we have always approached bringing instrumentation into Willard Grant which is to use it as an integral part of the songwriting. That then was the first notion. The second notion was to keep it minimal, because I didn’t want a grand orchestral thing. It is in some ways a lovely idea and now that we have this record I wouldn’t say no to putting on one or two shows with an orchestra but that wasn't the ideas of this record. None of the songs on this album are, however, really big songs, “big” in quotes. You know that moment in films when the score is too much, and you think, “Okay, they’re really manipulating me now. I got it. They don’t have to shove it down my throat with music as well.” The whole nature of an orchestra, whether it is playing good stuff or bad stuff, can be overwhelming, and I really didn’t want that for this record. It was really important to me to maintain an articulate voice for each instrument. I didn’t want to have big clumps and lumps of things. I wanted you to hear the bow on the strings on the cello. There is a moment on one of the tracks, ‘Jerusalem Bells’, when a cello comes in and your body vibrates with it. What an excellent moment that is!That was the sort of thing I was looking for with this record. PB : The album included contributions from several previous WGC contributors and there are also several new contributors on this record such as Iona McDonald and Paul Tasker from Doghouse Roses, Stuart Duffin and Rachel Morley. They’re all Scottish musicians. Were they people that Malcolm introduced you too? RF : Actually, Paul and Iona are people that I introduced him too. I met them originally through the miracle of MySpace I got a friend’s request from them and checked out their page and thought, “Hmmm, I like that.” The rest of the people are all people that Malcolm knew including the entire choir that appears on ‘The Great Deceiver’. There were a lot of people that he pulled in from his circle. PB : You got a lot of these musicians to send in their contributions from places like New York City, Cambridge in Massachusetts, and Slovenia. In the past you have tended to take the music to the musicians rather than let them send it to you. You must have had a lot of trust in them. How exactly did that work ? RF : I started doing that with ‘Let it Roll’, and also a little bit on ‘Regard the End’. I have never had a trust issue with anybody from the band, so it was not a difficult leap for me really. I love being in the room when things are being created and done, and that can be exciting. There have, however, quite often been times when I have not really been doing very much musically other than enjoying myself, so economically there develops this big question as to whether or not I want to afford to fly to different places and have that experience. In the cases of musicians like David Michael Curry, who has appeared on every record since ‘Flying Low’ , and Dennis Cronin, who has been on three records now, they like to work at their own pace in their own studios, and it gives them the opportunity to do that kind off the clock. The Willard Grant Conspiracy has always been about making room for people to contribute as is comfortable for them whether live or on the record, and that’s what happened here. PB : You have said that in the past that you see the Willard Grant Conspiracy “as examining the dark to see the light”. Do you think that is the case in this album ? RF : I do and I think there is maybe a bit more light on this record. The themes here are strong themes. They’re not necessarily difficult, but they are strong themes. PB : You have always said in the past that you’re not an unbeliever and that you have had some kind of faith in a higher power, yet ‘The Great Deceiver’ in particular point towards a questioning of faith. Would that be accurate ? RF : Yeah, I think so. The notion of faith as a permanent thing is a failed one. You don’t just say to yourself I have an understanding of this and then feel comfortable with it. Events come up all the time and unfortunately the older you get the more things play upon your notion of faith. There was a situation at the beginning of this year when one of the band members, Drew Glackin, passed away unexpectedly (Multi-instrumentalist Drew Glackin was also a member of the Silos and played regularly live with the WGC-Ed). You think to yourself, “44 is too young. There were plenty of good reasons why they shouldn’t have occurred.” There were plenty of good reasons why that shouldn’t have occurred.” Whether it is a big thing like an unexpected death or something smaller, there is always something in play. The idea behind ‘The Great Deceiver’ is that a lot of people wander around saying to themselves, “Where is my saviour ?” and “When are they going to arrive ?” You have to look to yourself in that situation. It is almost as important for you to know who the deceiver is in your life as well as who is the illuminator. It is only by knowing the deceiver, the failed side of you, that you can know the better side of you. That song really kind of nails that for me. PB : Is that then your optimism kicking in again ? If you know the failed side of you then hopefully the other better side of can come into play a bit more. RF : Absolutely, and by reflection you get to know which is which. Sometimes it is hard to define the difference between two sides. PB : The central character on ‘Lost Hours’ is lost in the desert. Jesus spent forty days and nights in the desert after being baptised resisting the devil. With what comes on the album, was there some kind of religious symbolism intended there ? RF : No, but it is a good notion. I wouldn’t discount it. If somebody were to see it that way, I would certainly understand it. There is a route called 138 which goes from my part of the desert over to a place called Gorman and which puts you on the way if you’re heading up North towards Fresno and that area. 138 is a long straight road through the desert. It’s only variances are through the dips that it takes where you kind of disappear from view for a moment and then come back out again. There have been a few times when I have had to make that drive having driven six or seven hours already and it is that drive which the song is that about. It is almost too much to handle that last section of the drive, but you’re almost home and to stop would be ridiculous. ‘Lost Hours’ is also about what happens to your brain during those periods of time (Laughs). Your mind does funny things to you on that drive. PB : The album includes two covers, ‘Miracle on 8th Street’ and ‘Phoebe’. Why did you decide to put those on the album ? What was the appeal to you of those songs ? RF : ‘Miracle on 8th’ is a song that I have been doing in concert for a while. Paul Austin asked me a couple of years ago to participate in an American Music Club tribute, a live thing which he did in Seattle, all the proceeds which went towards a charity At the time he asked me to do that, I said, “Yeah okay, but I don’t know what song to play” and he said, “Well, play this one”. I looked at the one he wanted me to play and I was like,”Naah, I can’t do that” and he said, “What about this ?” and I went, “Okay, that’s good” and that was, of course, ‘Miracle on 8th Street’ . When it comes to AMC I know to listen to Paul about these things because he knows more about Mark Eitzel’s music than anyone else on the planet apart from Mark himself. The song itself it is almost a song that I feel that a better part of me could have written. When it comes to covers I look for that, a song which fits me but maybe I am just not good enough to have done myself. Mark is a remarkable songwriter and an incredibly brave performer. ‘Phoebe’ is a Lal Waterston song . Charlotte Greig was doing a tribute to Lal Waterston, and she asked me if I would participate in it and I said, “Sure, but I don’t really know her music well enough to pick something.” She said, “Here, let me send you some stuff” and did and suggested this song. It was an a cappella piece that Lal had done which ends with a guitar solo, and I thought, “it’s a lovely song and it really does suit me, but I can’t do it just the way she has done it and we will have to write some music for it” and we did. I ended up putting it on the album because it is another song that fits the record very well and was recorded during the same session. PB : You also cover yourself on this record with a new version of ‘Painter Blue’. RF : The original version was for a Spanish double compilation CD, ‘Acuarela Songs’, which I don’t think,outside Spain, many other people ever heard. It is a song that I have always loved, but that version we did on the Spanish compilation was almost like a demo. It just featured David Michael Curry and myself, and it was something that we created in the studio just because we happened to be there. It was never really fully conceived, so I feel this is the more defined version. I don’t ever think there is anyone version of a song that is the perfect version, but this case it felt like revisiting it was a good idea. In a really significant way the journey that the main character in ‘Painter Blue’ goes through is very much a part of this record. Without that song, the record makes less sense really. There are things I like about the original that I like very much, but this one is great. Malcolm did a remarkable job with the arrangements on this one. PB : It also means that you get David Michael Curry on this album, who I think has been on every record now, but who otherwise doesn’t appear on this one. RF : Yeah, that was important as well. David is at this point other than myself the longest-serving active member of the band and it is important to me that he stays a part of things. PB : You’re going to be bringing a eleven piece orchestra out on the road to promote ‘Pilgrim Road’. Who is going to be out with you ? RF : Tom King, Erik Van Loo, Dennis Cronin, Malcolm ,Iona, Josh Hillman, Chris Eckman, Yuko Murata, a musician from Edinburgh named Peter Harvey on cello, and John Songdahl who mixed the record and who will be playing trombone and keyboards. That is the kind of rough crew. PB : You’re just doing twelve dates, aren’t you ? RF : With that ensemble, and Howe Gelb as support along as well, it’s seventeen people, including crew. The economic realities of that are pretty terrifying . It is costing a ton load of money out of my personal pocket to do it and I just don’t think I can justify doing any more shows than that. I know that I will be disappointing some people by not playing in their backyard, but the notion of bringing this show to everyone’s backyard would just be crazy. If anybody knows the history of what we have done in the past I don’t feel anybody can feel excluded. We have over the years taken great pains to play pretty much anywhere anyone has asked us. The exclusive nature of these shows will, I hope, not upset anybody. We are, however, going to be documenting the May tour with the idea of maybe making something available out of that. I can’t imagine putting together a band as fine as this and not attempting to record and film it. Hopefully that will go some of the way as well towards making it available to people who are not able to see it. PB : Will you be doing other shows as well to promote the album in a different form ? RF : With the exception of this tour, I don’t really think of tours as promoting albums anymore. I see them more as a way of making a statement about process. I think in the Fall maybe I’ll do something with a smaller ensemble, something that is a little more flexible and affordable. PB : You have got the May tour coming up. The album is coming out at about the same time. What other plans have you got for the immediate future if anything ? RF :In the last couple of months I have been in between working on this record working on some garage recordings in LA with a really rocky version of the band, which includes Kirk Swan (Dumptruck-Ed), Robert Lloyd, Tom King and a few other folks. I haven’t come up with anything that I want to share with anybody yet, but maybe the next one is going to be a kind of garage rock record (Laughs). I don’t know. It just depends on where things go. The songs we have committed to tape so far have been pretty fun and it is a remarkably good group of people to play with. What we have been doing so far is just setting up in a room and recording it live and not doing any kind of layered multi-tracking or anything like that, just setting up and then going. It has been great. There’s this immediacy thing that I really like about it. But who knows ? We’ll see what happens. I am certainly not the only person to have tried this kind of thing, but whether it will work or not I don’t know yet (Laughs). PB : Thank you.

Band Links:-

https://en-gb.facebook.com/WillardGrantConspiracy/https://twitter.com/willardgrant

https://www.willardgrantconspiracy.com/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Willard_Grant_Conspiracy

Picture Gallery:-

interviews |

|

Interview with David Michael Curry (2019) |

|

| Willard Grant Conspiracy viola player David Michael Curry talks to John Clarkson about its tenth and final album 'Untethered' which was completed after the death of its front man Robert Fisher during its recording. |

| Interview (2013) |

| Interview (2009) |

| Interview with Robert Fisher (2006) |

| Interview with Robert Fisher (2003) |

| Interview Part 2 (2000) |

| Robert Fisher Interview (2000) |

| Interview Part 1 (2000) |

live reviews |

|

Garage, London, 18/9/2009 |

|

| In an evening fraught with difficulties and distractions, Ben Howarth at the Garage in London watches Robert Fisher's Willard Grant Conspiracy, against the odds and a heavily reduced stage time, play a riveting and forceful set |

| Majestic Theater, Detroit, 24/9/2009 |

| Bloomsbury Theatre, London, 18/5/2008 |

| Luminaire, London, 9/11/2007 |

| Dingwalls,, London, 9/5/2006 |

| Edinburgh Village, 11/7/2002 |

features |

|

Ten Songs That Made Me Love... (2017) |

|

| In 'Ten Songs That Made Me Love...' John Clarkson pays tribute to Robert Fisher from the Willard Grant Conspiracy, who died at the age of 59 in February and who we interviewed many times and headlined our Bands Nights on four occasions |

reviews |

|

Untethered (2019) |

|

| Evocative tenth album from Willard Grant Conspiracy which features the last recordings of its front man Robert Fisher who died in early 2017 |

| Paper Covers Stone (2009) |

| Regard The End (2003) |

| Everything's Fine (2001) |

| Mojave (2001) |

most viewed articles

current edition

Carl Ewens - David Bowie 1964 to 1982 On Track: Every Album, Every SongArmory Show - Interview with Richard Jobson

Colin Blunstone - Thalia Hall, Chicago, 16/7/2025

John McKay - Interview

Visor Fest - Valencia, Spain, 26/9/2025...27/9/2025

Bathers - Photoscapes 1

Billie Eilish - O2 Arena, London, 10/7/2025

Robert Forster - Interview

Loft - Interview

Sir Tim Rice - Interview

previous editions

Heavenly - P.U.N.K. Girl EPManic Street Preachers - (Gig of a Lifetime) Millennium Stadium, Cardiff, December 1999

Beautiful South - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

Oasis - Oasis, Earl's Court, London, 1995

Trudie Myerscough-Harris - Interview

Prolapse - Interview

Pixies - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

Coldplay - Wembley Arena. London, 16/8/2022

Boomtown Rats - Ten Songs That Made Me Love....

Simon Heavisides - Destiny Stopped Screaming: The Life and Times of Adrian Borland

most viewed reviews

current edition

Amy Macdonald - Is This What You've Been Waiting For?Sick Man of Europe - The Sick Man of Europe

Phew, Erika Kobayashi,, Dieter Moebius - Radium Girls

Lucy Spraggan - Other Sides of the Moon

Davey Woodward - Mumbo in the Jumbo

Alice Cooper - The Revenge of Alice Cooper

Bush - I Beat Loneliness

Blueboy - 2

Suzanne Vega - Flying With Angels

Cynthia Erivo - I Forgive You

related articles |

|

: Interview (2023 |

|

| In the first part of a two part interview, both parts which we are running consecutively, guitarist Paul Austin talks to John Clarkson about the reformation of his band The Transmissionary Six after a decade-long absence, and their new album, 'Often Sometimes Rarely Never'. |

| : Interview (2023) |

| Willard Grant Conspiracy/Big Hogg: Feature (2015) |

| Tom Bridgewater: Interview (2015) |

Pennyblackmusic Regular Contributors

Adrian Janes

Amanda J. Window

Andrew Twambley

Anthony Dhanendran

Benjamin Howarth

Cila Warncke

Daniel Cressey

Darren Aston

Dastardly

Dave Goodwin

Denzil Watson

Dominic B. Simpson

Eoghan Lyng

Fiona Hutchings

Harry Sherriff

Helen Tipping

Jamie Rowland

John Clarkson

Julie Cruickshank

Kimberly Bright

Lisa Torem

Maarten Schiethart