In the 1950s and '60s, the revolutionary new wave of British Cinema put Northern streets onto the cinema screen . Whilst some of those British realist films dealt with challenging modern issues, there were largely two common threads which ran throughout many of them. The idea that the only way of having a better life was to leave your working-class Northern town and escape, usually to London, and the idea that any Northern accent was largely interchangeable. Ken Loach totally reconstructed British cinema. For the last 60 years, his films have highlighted real situations that affect real people and have authentic casting, preserving regional accents and dialects from the area in which that particular film is set. His films have been groundbreaking and have directly tackled important issues such as abortion and homelessness on screen for the very first time. He has been fearless in his approach and in his desire to document the lives of ordinary people and to continue to campaign against social injustice and inequality. Ken Loach is one of the most important film-makers of all time. PB: I was watching ‘Cathy Come Home’ yesterday and the first thing that struck me was that it was filmed in 1966 and it could have been made last week. The issues that are highlighted in that play are so relevant today and that's horrifying, isn't it? The same with ‘Up the Junction’. ‘Cathy Come Home’, was the first TV drama to talk about abortion, leading up to the Abortion Act in 1967. Can you remember what the reaction was at the time to these two TV plays? KL: Well, the reaction was interesting. The hostility was centred around Mary Whitehouse and the clean-up TV brigade because she didn't like to see kids up to the mischief that kids always get up to and, you know, just going out with each other, she hated that and she hated the fact that there was a story about a girl having a termination. It was something you didn't speak about. The response was pretty good, really, overall. Because it was a little film. I mean, it's very simply made, but it was a little film. And that was in a slot that was theatre. It was like televised theatre. So, to see something made like that was very different. And by and large people responded to it well. It was music and kids doing what kids do and their energy, I hope, communicated and their fun and mischief. And the hardship as well, in a way. ‘Cathy’ was a stage further because with ‘Up the Junction’, they didn't know we were going to make a film. We made it in the teeth of their opposition. We had four days to shoot film in those days. And that was meant to be people leaving one set, getting in the car and going to the next set in the studio. And we used those four days to shoot half the film. And then in the studio, for ‘Up the Junction’, you vision mix in the studio. You do the editing while they're recording it. And I purposely didn't let the shots run on too long and it didn't work. I purposely didn't vision mix. So, we ended up with a whole series of separate shots and the people in charge, the technical people said, “well, you can't use this film. No, you haven't vision mixed it. And it'll be too expensive to cut the tape.” So, we said - that's Tony Garnett, me as the producer - we said, “Well, we know there's a 16 -mil backup on film, everything that is made in the studio. We can use that, and then we can cut it like film”, which is what we did. And they were furious because it's very pure quality, but nevertheless, we did it. And it was the fact that we'd made a film almost without them knowing it, because management was very much more innocent then. I mean, it wasn't micro-managed like it is now. The next year we did ‘Cathy Come Home’, and that was a film, a three-week shoot, chasing around in different locations. It was (about) homelessness, what could happen to people who were homeless was a shocking story then. And obviously it's much worse now. But I guess in a way, by and large, the reaction was good, sharing the shock of people knowing that. Again, the right-wing attacked us and said they couldn't tell whether it was truth or fiction, and we said, ‘Well, is it true? Are these things happening?’ That's the only question. And yes, they were. But ironically, as you were saying, they could be made now. And homelessness, of course, is much worse now. But in a way, that's not surprising because it's the same, housing is still the market. And the building industry will build, or the developers will build, luxury flats in the centre of London, which are used in investments, but they don't build affordable houses because they can't make the same money from it. And it's because it's a market. It's like you were saying about care. They're in it for the money. They're not there to satisfy our social needs. PB: But it is an awful realisation, isn't it? KL: It really is. PB: What is it that has made you want to document or to tell the stories of the lives of ordinary people? KL: Two reasons, I suppose, one is the culture I know. My dad was an electrician in the factory, although he did quite well and became a foreman, and then he was in charge of maintenance in the big machine tool factory. But he was from a family of ten who were all miners apart from him, the men, in the Warwickshire coalfields. In his mind, he was working-class, he was the marrow of his bones, really. My mother had been a hairdresser and we had a nice life. We lived in a semi-detached house, which was very ordinary, but nice, which they were very proud of. We used to get a Blackpool for the holidays once a year, seeing the comics on the piers. Just that working-class life is what I knew. Although, I guess, we were a family of a skilled worker, so in social terms, economically, we weren't poor, we were just ordinary. The working-class have the best jokes. The stories are much richer in their human content. For people who don't have much money, the conflicts are much more serious, and the dilemmas. The choices they have are much more limited, and the need to rely on your neighbour is much more real. So relationships are coloured by that need. And the stories are just more interesting, the emotions are more raw. Middle-class life tends to be very neutral. Boring. Tedious. Not so interesting, not to me anyway. So, there's that, but also, I think, politically, the working-class is more important. I mean, if there is to be change, to get us out of the terrible mess we're in now with the climate disaster, on top of the poverty and the exploitation of work, and everything that's going wrong, like the collapse of public services, the only people who can make the change is the working-class. We're led to believe they're weak, but actually they have the power to stop the wheels. The working-class doesn't need the private investors and the big companies, the corporations. They need the working-class to make their money. So, you know, if the working-class had the leadership that said that, we could really make changes, but the leadership has always been compromised. Apart from Jeremy Corbyn, who did lead in a more positive direction, you know, Tony Blair, Starmer now, they won't change anything, because that's their politics. Labour has always been right-wing. From day one, pretty well day one, the first Labour government was led by a man called Ramsey MacDonald. And he had nothing to do with the General Strike (of 1926), he walked away from it. And they all left the Labour Party leadership and joined the Tories. Atlee was a right-winger, though he established the welfare state because public ownership was established in the Second World War, just for efficiency. And the Tories, in a way, were prepared to continue that. So the welfare state happened and it was a great achievement but within the party-political spectrum, Atlee was quite a right-winger, as was Wilson, Callaghan, Blair, Brown, and Starmer. They destroyed Corbyn because he would make changes. PB: It was awful. KL: In a way, it's no surprise that homelessness is as bad as it is because it's a product of the market economy. PB:, Were you influenced in any way by the new wave of British cinema in the late ‘50s, early ‘60s? KL: Well, at the time, the little gang I was with, we were a decade younger, I suppose, than those directors and writers. And we were, in our youth, very scornful of it. Because we said, well, they're West End actors, they're West End directors, and they're up there as tourism, you know? The North of England was tourism for them. And they did one, two films each, and then they went away. It was opportunistic, we thought. But looking back, of course we saw them, and of course they were influential because they did put those streets on cinema screens, the working-class North was on the screen. And that had never happened before. So, in a sense, in our youthful arrogance we were quite dismissive of them, but they did nevertheless make an advance. PB:nThere didn’t seem to be that many films which used regional dialects, in the way that perhaps ‘Hobson's Choice’ and ‘Saturday Night and Sunday Morning’ did. I think you really set a precedent with that. With your films, you were very interested in making sure that the regional dialects stayed and that it wasn't turned into something that it shouldn't be and that it wasn't. It had to be real, right? KL: I think then it sounded like ‘Saturday Night and Sunday Morning’, and I mean, it was Albert Finney from Salford, pretending to be Nottingham, well, he isn't. Anyone who knows Nottingham knows that it’s nothing like Salford or Lancashire. And there was a sense that anything North of Watford was a Northern accent, and it was all interchangeable. There was that sort of casual arrogance about the North. But they made advances, and it would be churlish to say not. But then, we, I say ‘we’ as the writers I worked with, plus Tony Garnett, who was the producer I worked with in the early days, we just said, well, we can take it further now, just to make it really as authentic as we possibly could. Both in the casting and in the writing. And particularly in the stories we tell, because the interesting thing about that new wave of those early films of late Fifties, early Sixties, a continuing theme was getting out of the North to London. PB: That's true. KL: ‘Billy Liar’: escape. And ‘A Kind of Loving’ was wanting to escape. And what a patronising, again, middle-class attitude to have. I mean, people don’t want to escape, they just want a better life, but they don’t want to escape. And what a kind of Londoncentric idea. You know, the only way you can live is to leave. And I guess there's a political attitude to that, really, which is not a celebration of working-class life, it's scorn for it. You know, you've got to get away. I mean, there was a song, was it the Animals’ song? PB: 'We've Got to Get Out of This Place.’ They were from the North-East ,weren't they? KL: Yeah, yeah. And they went to California or something. PB: But maybe that's why, as we were saying before, that's why the towns are dead. You know, the towns where I grew up. All of the people of my age have moved on, moved out. It's the fact that there is nothing for them in the towns. I don't know what it is, really. KL: Again, if it was a different political system you would, as the old industries died - and of course industries changed, I mean, that's normal, it's inevitable - but you would plan that. You would plan the transformation. There would be public investment into new industries. People would be retrained and it would be gradual or over a period of years. So, the people could carry on working, but then would learn new trades or adapt their existing trades and skills. And you'd plan it. Take advantage of the newest technology. Of course, new technologies should be our friend to make work easier, not to speed up production and sack half the workforce. But of course, again, the market economy drives the chain. So they will just walk away. No more money to be made, take the investment out of there. Or put it where labour was cheap, put it in the Philippines or put it in Indonesia or Taiwan. Wherever the workers are cheap. India, China, wherever they can... Well, not China because that's the state investment, but the industry goes to where labour is cheap, which abandons the people, as you say. PB: You lose the humanity, I think, in favour of a profit. And I think that is particularly well depicted in ‘I, Daniel Blake’, where he's on the computer, really struggling, he doesn't know how to use a computer to fill out the form for the Jobseekers Allowance and it keeps timing out. I think it really encapsulates the frustration that he and everyone else faces when you're waiting to be connected to an automated voice on the phone or your session times out on the computer because the humans have been removed in favour of the cheaper option or the computer. KL: And if you're phoning your bank, you're phoning India. And you know, the people there get exploited so you can't express your frustration to them. I mean, they're just trying to earn the money to live on. But the frustration is that the bank is making profits from cheap labour, regardless of the effect on either the people they are employing, the people they've sacked, or the customers. PB: Just while we're on ‘I, Daniel Blake’, I guess the great thing about any kind of media, if the reporting is accurate, is that it allows you to understand situations that you've perhaps not been in yourself or at least gives you a window into that. The situation that Daniel is in in the film, where he has been rejected from the Employment and Support Allowance, he's having to go on to Jobseekers Allowance and is being forced into a position where he's having to seek work against the advice of his doctor. The additional pressure on top of that is that if he hasn't met some sort of standard of searching for work 35 hours a week and can prove it, then he will be sanctioned, that part alone is such a fascinating message to anyone that's watching, of the reality of what actually goes on in the state. KL: Well, it's punishment. It is punishment. You're punished for your poverty or you're punished because you belong to a generation that doesn't get the new technology, is not very good at it and not quick enough. And it's not about enabling people to work or to do well or to make the contribution they can given their circumstances. There's a kind of punishment. It's the same as the Poor Law when they used to punish the sturdy beggars in the Elizabethan age or the workhouses, which were the terror of people, not to go in the workhouse. Now it's benefit sanctions. We discovered there are targets. There are clear targets, if enough people aren’t sanctioned or put on personal improvement plans or whatever they’re called. It was denied but we had hard evidence. PB: So they have to sanction so many people? KL: Yes. They’re expected to. The people who do well, i.e inflict many sanctions or people don't do so well. We heard that from several sources. PB: It's horrendous. KL: It is horrendous. I mean, that research was three or four years ago but that was certainly the case. And there's no reason to suspect this has changed. PB: No, it's frightening. KL: It is. It is. And it's a decision by the state. And the logic is there's got to be a certain level of fear to drive people to do appalling work at exploitative levels of paying conditions. PB: It's incredible. It really is. It reminds me when my mum was still able to work, she'd had the same customers for 40 years in the chemist’s where she worked and when her little independent family-run company got bought out by a big corporation, she was told to spend less time with her customers and to upsell products, she was told she had to ask them if they wanted stamps or a mobile phone. She would explain that she knew that her customers didn’t want stamps or phone top-ups because she’d been serving the same customers for 40 years! Of course, this fell on deaf ears. KL: Well,. that's what management is. taught isn't it? A customer is welcome but a problem if they talk too much. You've got to move them on. PB: And a customer is an opportunity to sell more to. KL: What a pity. Again, that's the other pity, it's monopoly, isn't it? The big ones eat the small ones. PB: So, when you're making a film, Ken, are you simply hoping to bring the matters in the film to the attention of a greater number of people or is it more to document what's going on socially? KL: I’ve been working with Paul Laverty for 30 years and we look for stories and situations that are significant. It may look a small story on the surface but it should be like an iceberg. So that it has resonance and truth in the way people conduct their relationships, in what they do, in who they are and there's a truth in that and the truth is a wider truth than just simply those chosen people in that small situation. And it's important and significant, like the relationship with Daniel Blake and the young mother. There's a truth in their relationship and their exchange and how they begin by not knowing each other to then support each other and look after each other a bit. That develops bit by bit and I hope it's not sentimental, there's a truth in it. It's thinking about it and relationships between a man and a woman, or kids and parents, and all the rest and people at work which we've done a lot of, and people in wars. Once you're making the film, it's the truth and the authenticity of that that matters, but when we're choosing a story and when Paul's writing it, I think Paul's contribution is probably the prime creative act because it's his characters, his story and his dialogue. In a way the biggest decision of the whole film is what story? Who are the people? Why are they important? What do they reveal? What's the storyline that will reveal the essential conflict that they're involved in and how is the conflict resolved? You know, basic dramatic structure. But the characters and the story should reveal a wider truth than simply what they’re doing. PB: I've got to talk about ‘Kes’ for a moment. I saw it on the big screen for the first time just before Christmas. In Barnsley with David Bradley. (Bradley played the lead role of Billy Casper in the 1969 film.) KL: Oh right, very good! PBL So, it couldn't have been any better other than having you there! KL: Right, but where was that? What was the occasion? PB: I’m not sure what the occasion was. There is a Cineworld cinema at Barnsley and they were showing ‘Kes’ for a week and they'd asked David if he'd go along and do a bit of an introduction and a Q&A. And he did and it was just wonderful. I could talk about ‘Kes’ all day, I really could. I've seen it so many times, the opening music is wonderful. Where did the music come from? KL: There was a guy called John Cameron who wrote the music. The essence of it all is in Barry Hines' book, which is a wonderful book, and modest. The great thing about Barry and Jim Allen and Paul Laverty is there's a kind of modesty about what they try and do. It isn't self -proclaimed, ‘I'm the greatest, look at this great thing.’ It's just a modest recording of what's going on really and things from the past. Barry's book is so beautifully observed and the dialogue is so pitch-perfect. His sense of comedy is so brilliant and warm towards the people, these characters and the dialect. We did a lot of films together and we were always giggling away in the corner, just listening to the language. Language is much undervalued in film actually, much undervalued. I think it's enjoyment of the people, enjoyment of the humour of them. But the essence, the central point, it's about wasted talent. The other thing that is brilliant about Barry's book is the central image of the boy who is trapped in this world where his only alternative is unskilled, and probably down the pit, which he doesn’t want to do and the bird that flies free. You've got the two images and that, as a piece of writing and therefore as a piece of cinema, which is Barry's idea, that's the image that in a way touches people, I think. PB: I think one of my favourite scenes in the film is the intimacy of the scene where Billy is showing Kes to his teacher. It's the bit where he says it's fierce and it's wild and it doesn't care about me, but that's what makes it great. That shot is just so intimate and so close and so quiet. And it's beautiful. I love that moment in the film. KL: I mean he was brilliant, David. We were really lucky because all the cast, apart from one or two kids, and Colin Welland obviously, but all the kids were from a two-form entry. So, I mean the class is David Bradley's class. Just the class. But one or two added kids. And that was it. PB: One of the nice things about watching it in Barnsley was that all of the people that sat around me, all the way through the film were saying things like, “Well that's just over there. I remember that.” And it was great, because where would you get that? You're sitting with people, this is a film about them and about their town and I'm sat with them and they're describing everything. So, it's a good job I'd seen it before because I wouldn't have heard all of it! An interesting point that I read was that American executives at United Artists claimed they would have found a Hungarian film easy to understand, which whilst it might be true, I feel somewhat misses the point a little bit. KL: Well, we got the money finally because Tony Richardson had done a film for them called ‘Tom Jones’. PB: Which was a big success! KL: Yes, and so they thought what he touched turned to gold. And so on his word, they backed the film without really seeing it. PB: Was he a friend of yours? KL: No, he wasn't a friend and I can't quite remember how we got in touch with him. I think we were writing around to everyone. PB: Was he part of Woodfall Films? (The production company behind ‘Kes’.) KL: Yeah, yeah, he was. PB: So there's got to be a connection now, isn't there? KL: Yeah, yeah, absolutely. But they didn't know what to do with it. It had its premiere in Doncaster. PB: Yeah, the world first! KL: Yeah. And the Barnsley MP, it was Roy Mason. He was a right-winger, absolute..Not an MP we would warm to. He came along to the premiere and was obviously bored to tears. We ended up having an argument with him, me and Tony. PB: Thank you.

Band Links:-

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ken_LoachPlay in YouTube:-

Picture Gallery:-

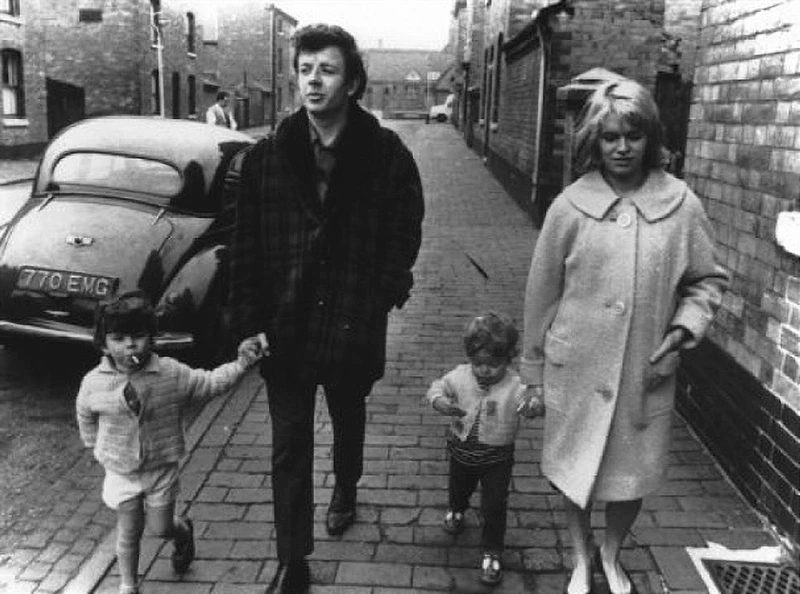

Up The Junctiiom

Cathy Come Home

Kes

I, Daniel Blake

intro

Adam Coxon talks to film director Ken Loach about his long career and the making of his films including 'Up The Junction', 'Cathy Come Home'. 'Kes' and 'I, Daniel Blake'.

most viewed articles

current edition

John McKay - InterviewCathode Ray - Interview

Robert Forster - Interview

When Rivers Meet - Waterfront, Norwich, 29/5/2025

Spear Of Destiny - Interview

Fiona Hutchings - Interview

Carl Ewens - David Bowie 1964 to 1982 On Track: Every Album, Every Song

Chris Wade - Interview

Shrag - Huw Stephens Session 08.12.10 and Marc Riley Session 21.03.12

Brian Wilson - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

previous editions

Heavenly - P.U.N.K. Girl EPBoomtown Rats - Ten Songs That Made Me Love....

Manic Street Preachers - (Gig of a Lifetime) Millennium Stadium, Cardiff, December 1999

Allan Clarke - Interview

Oasis - Oasis, Earl's Court, London, 1995

Barrie Barlow - Interview

Beautiful South - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

Chuck Prophet - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

Pixies - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

Dwina Gibb - Interview

most viewed reviews

current edition

Peter Doolan - I Am a Tree Rooted to the Spot and a Snake Moves Around Me,in a CircleVinny Peculiar - Things Too Long Left Unsaid

Garbage - Let All That We Imagine Be The Light

Vultures - Liz Kershaw Session 16.06.88

John McKay - Sixes and #Sevens

Little Simz - Lotus

HAIM - I Quit

Pulp - More

Lapsley - I'm a Hurricane, I'm a Woman In Love

Billy Nomates - Metalhorse

Pennyblackmusic Regular Contributors

Adrian Janes

Amanda J. Window

Andrew Twambley

Anthony Dhanendran

Benjamin Howarth

Cila Warncke

Daniel Cressey

Darren Aston

Dastardly

Dave Goodwin

Denzil Watson

Dominic B. Simpson

Eoghan Lyng

Fiona Hutchings

Harry Sherriff

Helen Tipping

Jamie Rowland

John Clarkson

Julie Cruickshank

Kimberly Bright

Lisa Torem

Maarten Schiethart