Philip Parfitt - Interview Part 2

by Denzil Watson

published: 7 / 4 / 2021

intro

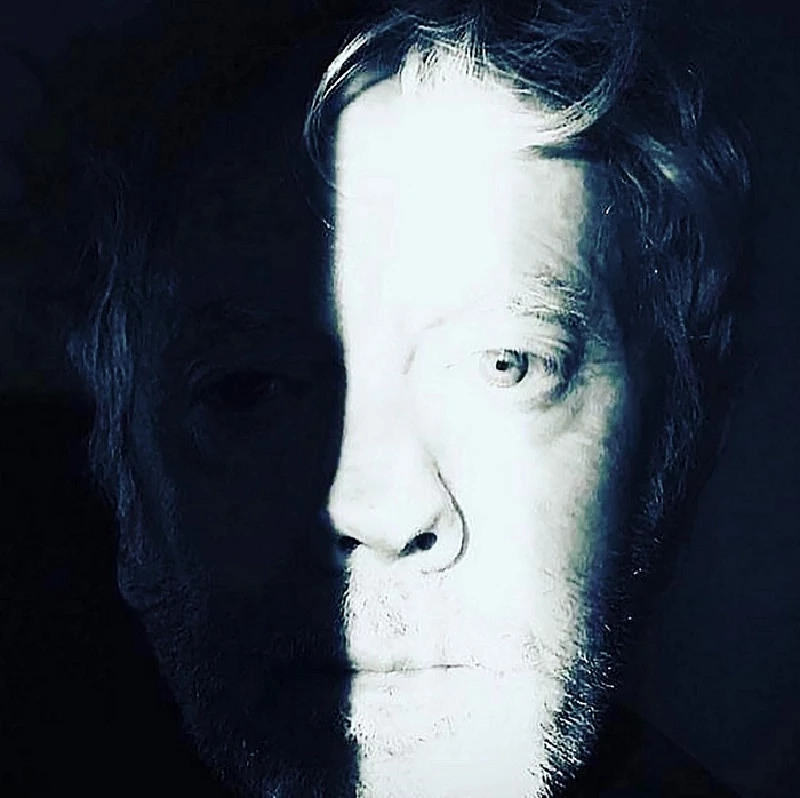

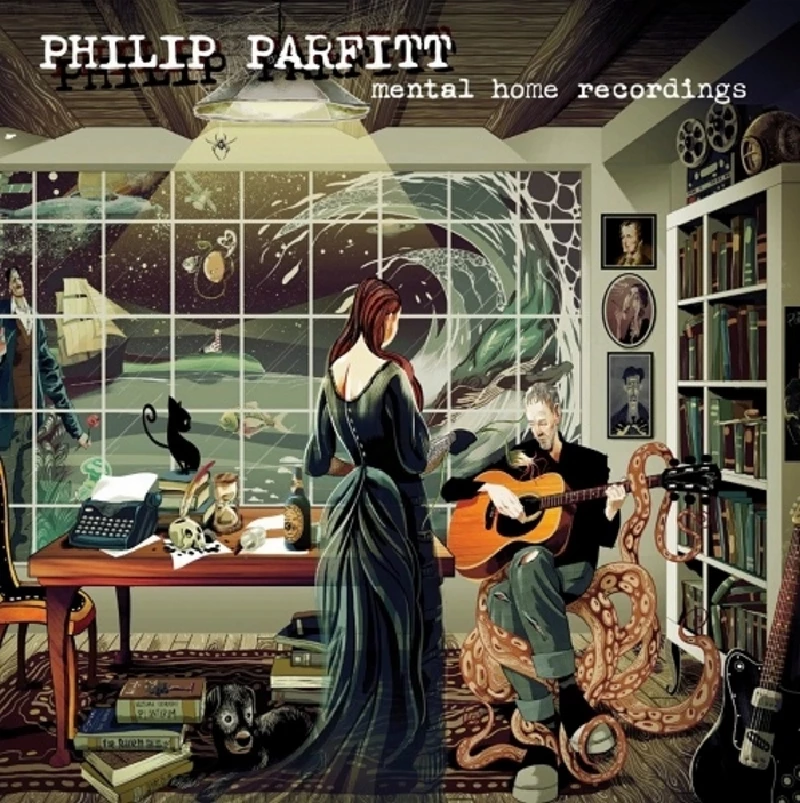

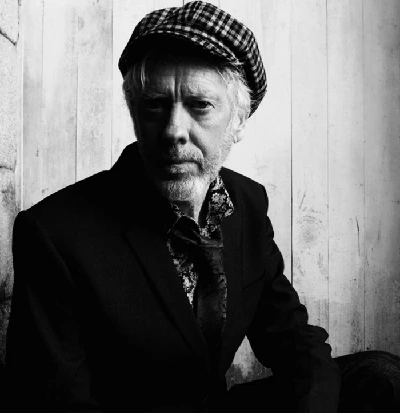

In the second part of his in-depth interview with ex-Perfect Disaster frontman Philip Parfitt, Denzil Watson speaks to him about his influences and new solo album, ‘Mental Home Recordings’.

Pennyblackmusic: What was the ethos of The Perfect Disaster back in the 1980s? Philip Parfitt: I wanted to do a very stripped-down kind of rock and roll show, but with every bit of pumping on all four cylinders. I never really got into the kind of shambling aspect to it. If ever anyone called us or tossed us in the ‘shambling’ lot, I didn't really like it. I wanted it to be a well-tuned engine just, you know, pumping. That was more my kind of style really. I think that comes across on ‘Up’. Everything on ‘Up’ is recorded live really. So, on the ‘Down’ suites that are on ‘Up’, the middle section part of the song is quite interesting because I had this motif that I wanted to extrapolate into this kind of orchestral thing, which the first part and the last part are. But in the middle of the one-time rehearsal when we were going through it and getting ready to record ‘Down’, Dan [Cross] just started playing the root chords of the piece with a really nice groovy feel. And I just started singing, ad-libbing, and so the finished version that came out on the album was an exact copy of the ad-lib lyrics of the time. So, I just sang it once and. as it was going, we had we recorded a lot of rehearsals and this was recorded, and I listened to and I thought, “Ah, that sounds really cool. Let's work it up”. So, what you hear is just the ad-lib lyrics and it's lucky at that particular time it was coherent in some kind of stream of consciousness poetry. And we worked like that a lot. I was very much into capturing the moment and when the moment was caught, work it, and take the energy. PB: Just like they say, when you play in the studio, it's normally the first take that is the best. And as soon as you get into more takes, you get into diminishing returns. PP: Yeah, it is. I think that for ‘B52’, the studio version , there are two or three takes. And they were all good, but we were high, pumping on energy at that particular time. So, we recorded three takes very, very quickly. And we just chose the one that was just grooving all the way. But they were all pretty similar and we could have chosen any one of three of them, but they were all at high energy. There may have been one that was slightly more up-tempo than the others. And we chose that one because it had the energy. PB: Going full circle from that, in terms of recording ‘Mental Home Recordings’, you were working in a really, really different way, weren't you? Or were you? PP: Well. In some ways, yes, and other ways, no. The method I've got of recording at the moment is a kind of mix of old-school type recording and modern technology recording techniques. For the pre-amp stages of the recording, I've got a 70-year-old Revox reel-to-reel that I use as my pre-amp stage. And then I’ve got another pre-amp stage, but it’s all valve and all kind of old school techniques. But then, obviously, that all gets put into software that I use to organise everything really. And that just saves me the trouble of spending weeks in a studio elsewhere, when I've got completely the means I need to have a sophisticated home studio. I mean, you know, if The Beatles lived in Abbey Road, you would call it their home studio, wouldn't you? I’m not saying I’m The Beatles or anything like that, of course, but I'm just saying that where I live is where I work and it's a studio. PB: When I said that it’s different, I guess what I was getting at is that you're obviously not playing with people and vibing with people, so in that sense, it is quite different. Or are you sometimes playing and vibing with the likes of Alex [Creepy Mojo]? PP: So, for Alex and me, we meet from time-to-time to record, but I usually, because he lives so far from me, send him this stuff and we correspond by mail and transferring recorded files. But then I plug them into my system, and do my kind of hocus pocus on it, and then blend everything in with what I'm doing. But other players, like Alex, come here to my home studio and play. Like last week, for example, I was recording trumpets here for a part on some songs that we recorded in the last sessions, but I've reopened them to make part of the next album. So, it's just la sort of never ending or ongoing process, although I did have a little break from recording recently, because I just needed to recharge myself a little bit and come at it from a slightly different angle. It’ll probably end up sounding exactly the same now that I have said that. PB: I have to I have to say the production is just fantastic. You've always written really good songs., but I think when you're at your best is when you write really good songs and you really produce them in exactly the way that they need to be produced. And the production on the current album, for me, is just flawless. PP: It was a really nice thing to say that. PB: The results are like you booked into the top of the range studio with a producer who you are really, in tune with. It's that sort of result. It's a very good product. PP: Well, thank you. So basically, it’s like I went into a studio and I plugged into myself. That's what happened. PB: There's been quite a big step up between ‘I'm Not the Man I Used to Be’ and ‘Mental Home Recordings’. For me it’s just gone up a notch. Not in terms of the song-writing, but in terms of having the confidence to take the songs and make them sound really cinematic. You've been ambitious in how you make them sonically and you've got that ability. You don't want them to sound like a little whimper in a big valley, do you? PP: So, with ‘Mental Home Recordings’, it was just totally me in terms of the mix and the production and the arrangements. I probably was able to see it through in a single-minded way that I probably haven't done since the ‘Oedipussy’ stuff, and certainly I didn't do that on the second ‘Oedipussy’ album, that didn't see the light of day, as of yet. But I suppose that I, out of necessity, assumed the role of producer. PB: And that’s not always easy, is it? PP: I don't know if it's not easy. Logistically, it's quite difficult because you're doing everything like engineering, mixing and all the production details. You're there, involved in everything. And when you're an artist who turns up and you're working with a producer and there are loads of staff and engineers around to take care of every little detail, you've got the confidence to let them get on with it and hope that everything's coming out right. But this time, I knew that everything was going to come back to me, and I was a little bit trepidatious about it at first, thinking, “Do I really know what it is I'm doing and where is it going?” But. I just thought. “Fuck it, let's try to find out where it's going". I'm not scared of putting out stuff that is slightly experimental or very long or very sparse. That's always been part of my oeuvre. I don't care about that kind of stuff. I mean, wow, going back a bit. Right, so let's think about the first single I did as Orange Disaster, which was a three-piece, and at the time, I thought sounded good. But then there were periods in the last thirty odd years where I thought, “Oh my God, that sounds awful”. But, then again, when I listen to it, I think actually that's quite innovative to do that. And some people have actually said to me, “Jesus, that sounds like the earliest hip hop record I've ever heard” because it's this strange, very sparse, slow tune that is six minutes long. But it's got a samba beat or something like that, you know. So, it's not the beat that you would normally put within that particular type of song, and the vocal doesn't come in for about a minute-and-a-half. Now, when you think of putting that out as a single, is it not necessarily brave, but I suppose it is a little bit brave or something if you're thinking about that you're going to get airplay and nobody's hearing the vocals for a minute-and-a-half. I think most people have like switched off. PB: I’m sure “the manual” says you've got you've got to hit the hook line 47 seconds in. PP: I didn't really think about it at the time. We just put out the piece that we wanted to do, and I remember playing it to Geoff Travis at Rough Trade and he said, “Yeah, yeah. We'll distribute that” because I had recorded it and pressed it and put it on my own label and he and he said, “Yep, we're definitely putting that out. We will distribute that” because he just likes it because he probably thought that it was brave or “out there” enough to do at that particular time. So, in terms of being able to do that kind of thing, it just seems like water off a duck's back to me. I just think, “Yeah. That's what I want to do. So that's what I'm going to do.” And the only times where I've slightly come unstuck in those terms is when I've listened to other people's opinions, like record companies or too much influence from other people within the band or producers et cetera, et cetera. And whenever I think about or listen to old stuff and I think, “Yeah, that's right”, it's usually because I've been able to go through with what I originally saw as the plan. And I'm not saying that I can't “go with the flow” and things happen, and they change direction, and whatever, I haven’t got a problem with that, obviously, as long as I still like it at the end, but there have been being times where I thought. “Oh fuck! Why did I listen to that person"? And the usual vibe of the record company is that if they like one song and it's successful, they will say it's enough. And this happened to me a lot, for example, when we were signed to Fire. They said, “Why don't you write another one like the other one?” And I just thought, “Oh, my God, why am I listening?” PB: Labels who are supposed to understand artists, right? PP: Yeah, exactly. These are the kinds of situations where I realised that everyone's got their opinion and they're entitled to their opinion as they're putting their money behind it. And they want to hear a certain something from a product that they've potentially heard somewhere in your repertoire. But as soon as you start trying to replicate repertoire, for me, it's dead in the water, from that point on. But I've got no problem with just recording stuff and thinking. “Okay. Right. This sounds cool. Where can I go with this?” So, for ‘Mental Home Recordings’, I had a lot of time on my own. I've got a hell of a lot of instruments in this room where I am now, and I can play them in a way that, shall we say, is unconventional. I wouldn't call myself a guitarist. I am somebody who comes to the guitar with an open mind and I play stuff. My technique is probably hopeless. Well, it is hopeless. As for my ability to go round, up and down the fretboard, I rarely go up the dusty end of the neck because I don't know what I'm doing. All my guitars are completely tuned in different ways. I don't play any standard tuning. And I'm a left-handed person who plays the guitar right-handed. So, it's completely unconventional. I just come to it with an open mind and I do stuff that maybe other people wouldn't do. And maybe some of my stuff is very repetitive, but it suits me. And if I come to something with an unconventional way of looking at something, that means I'm open to the experience of doing something, where perhaps some other people might not go for it. An old thing that they that they say in Zen teaching is that a beginner’s mind is open to experience, so the world of opportunity is very open. But with the expert mind, there are very few choices because he is trained to be an expert in a particular way of being. So, I come at it like a child, like everything's new. Every time I pick up the guitar, I'm like a kid. PB: Nothing is off limits then. If it feels good and it sounds good, then do it. PP: Exactly, exactly. No preconceived idea of how a guitar should sound. PB: If you don’t come at it like that you could be ruling out things that potentially could work and be quite interesting, couldn’t you? At the end of the day, anyone can pick up a guitar and strum out a standard song. But really, it's about trying to say things that are a bit more interesting, isn't it? Something that makes you think a little bit. PP: Well, I suppose, I can play a few songs by other people. I can play a few Velvet [Underground] songs. I can play a few Dylan songs. I can play a few Bowie songs. I can even play a couple of Nick Drake songs. But I don't think about playing other people's stuff. I just do it for my own amusement. I don't think about learning a thousand different songs. I've got some amazing friends who are incredible players who just literally can play hundreds of songs from the 60’s, 70’s and 80’s, you name it. But I've never really been interested in that, except for in the very early days of The Perfect Disaster when, to be fair, we were only a few short steps away from being a Velvets’ covers band. At some point, when we used to do our very, very early shows, there may have been six Velvets’ numbers in the set, you know, and a few of our own. PB: But that’s okay. Most bands start out like that. PP: I wasn’t worried about it. It was just where we were coming from and at that point, in the very early 80s, nobody or not very many people were doing Velvets stuff. And I just thought it definitely needed to be heard and definitely needed to be done. And I had no qualms about doing it. But I think if we weren't doing it half as well as I thought we were doing it, we probably wouldn't have done it. But I was happy with it. So, we were doing it. And then we were still crafting our path at that point, so it was all part of the process. I've not got a problem with going to people and saying that I was a massive Elvis fan or a massive Bowie fan. The stuff that I really liked, I was really into, like the early rhythm and blues music, like Jimmy Reed and people like that. They're the nut and bolts of where the Velvets came from as well, you know? This kind of music needs a massive respect. So, the Velvets took it in another direction, but you can still see it in their stuff. I can still see the rhythm and blues. Lou Reed was a massive rhythm and blues fan as well as being a jazz fan. And that's another area where I’d quite happily go. I haven't got any problem with it. I listen a lot to [Charles] Mingus and [John] Coltrane. These people are just phenomenal. If you don't want to listen to have that experience, you're cutting yourself off. I'm very open. Alice Coltrane, her stuff is amazing. There’s just so much incredible music out there. I must be honest with you. I don't listen to heaps and heaps and heaps of new music. Especially, I don't listen to much new psychedelic music, because to me, a lot of it, not all, does sound like it's stuck in a groove and they're trying to replicate stuff that was done forty or fifty years ago, but without bringing anything else to the table. There are some exceptions and there are some amazing new bands from the last twenty years. But I don't want to be seen as being someone is trying to replicate a particular period of music and definitely not call it psychedelic. The whole term of psychedelic, to me, was that it was experimental music that had never been done before. So how can you do something that's never been done before if you're still doing it sixty years later, but with a different colour fuzz box or whatever? How many hundreds of effects pedals do you need? So, if people want to go down that route, that's completely fine. Pure volume and pure noise are an experience to see live, but, however, it doesn't really float me in an emotional way. I'm probably going for something that goes for a different kind of purity. In that sense I'm probably searching for a pure sound, replicating the sound in my head and trying to get that as a recorded sound. That’s the kind of challenges I'm setting myself, and then it's about performing the pieces as well as I think it can be performed, or that I can perform it, or it should be performed. PB: One of the things I said right at the start of the interview is that you've got this feeling which you're translating into the music. And if you do that successfully, you listen to that song and you feel the emotion that you are feeling. PP: I'm hoping that that is the case. But I'm pretty sure that I can't always tell if I'm doing that. So, for example, some of the songs on this album, let’s take ‘All Fucked Up’, the vocal take that you hear on there is an ad-lib. It's the ad-lib demo vocal. I tried to redo it, but I couldn't capture the original vibe. So that's why the phrasing is a little bit funny because I'm still finding it. The gaps between the phrases are slightly long and potentially unconventional for a format pop song. It's a bit odd and I did transcribe the ad-lib and I did try to make sense of it. So, I've got pages and pages of this excellent script that I wrote, and I recorded various versions of it. And then I though,t “Oh right. Yeah, actually. Oh, fuck it! Let's just go with the original”. PB: It doesn’t really distract from song and I think it's probably one of the strongest on the album. PP: Well, it is the most up tempo and it's potentially the most punchy so it does gravitate the senses towards it, in that way. I can see that it is probably in terms of like radio play, apart from it being killed ‘All Fucked Up’, the one where people could actually say. “Oh, right. Yeah. We can bung that on as it's a bit like is old stuff.” PB: The video really complements it, and the one for the first single, ‘Somebody Called Me In' too. PP: Yeah. That's my friend Luigi. PB: The videos really sync with the songs perfectly. In the old days you used to be able to get in the studio. It was an effort to go into the studio, but to get a video done you used to have to have a big record company behind you. Now, it's very much a level playing field and you just need somebody who's creative. PP: Yeah, he's a very, very good director and cinematographer. And he did it because he wanted to do it. He loves my stuff and he's been a fan for many, many years. PB: And you can tell that. They just seamlessly meet each, the song and the video. PP: Right. I'm glad you think that. That's really cool. He's a talented fellow and the actress, she's very good as well. So, yeah, it welded together nicely that. PB: Yeah, it works. I wouldn't even use the word welded as that sort of implies things are being forced together. PP: Okay yeah, it glued together naturally. He got into the vibe for sure. PB: How did you go about deciding which songs would go on the album and which to release as singles? PP: The reason that these songs were chosen is because that there is a coherence between them. There is a narrative in the whole album. It's all about the world as viewed through the eyes of one particular character through a very long period of his life. PB: Is that character you? PP: No, it's not me. It's definitely not me. You could make of that as what you want. People will say it's me. PB: The reason I said that is, for me, it feels like a very personal album. PP: If I said to you “it was me” what would that mean? PB: Good question. PP: And if I say to you, “it wasn't me” which I just did a minute ago, what does that mean? I'm a character writer and if I have got a gift, if there is such a thing, I can seamlessly put myself into the position of the people in this. So, okay, to answer your question truthfully, there is a lot of me in the characters within this thing. So, I'm taking them into places perhaps where I've been, and I'm taking them to places where I might have ended up. And what is the word for that thing? Okay. I'm a massive empath. That's probably what I am. And I am hypersensitive. So, for example, I see a homeless person, and I’ll be the one who ends up talking to the guy for an hour. If I'm sitting in a park, it'll be a homeless guy or a mad person or somebody in distress who will come to sit next to me and tell me their life story. I'm just one of those people who is like a bloody conduit for these people. It's just about communication. That's where it's all coming from and all of those characters could be me. PB: So, is it the world seen through the eyes of one character or a series of characters? PP: It’s the world seen through the eyes of a particular character, but he is seeing his own world through the eyes of how things might have been. I think we're rambling now, mate! To be honest, I don't know where this stuff comes from. It just comes through me. I know that I'm someone who receives information and I just write it. I don't know where it's coming from, if you really want the honest answer. PB: Thank you.

Band Links:-

https://www.facebook.com/p.mused.on/https://twitter.com/philipjparfitt

https://philipparfitt.bandcamp.com

Play in YouTube:-

Have a Listen:-

Picture Gallery:-

interviews |

|

Interview Part 1 (2021) |

|

| In the first part of a two part interview, former The Perfect Disaster frontman Philip Parfitt speaks to Denzil Watson about his second solo album, 'Mental House Recordings', and his return to music after an absence of many years. |

bandcamp

soundcloud

reviews |

|

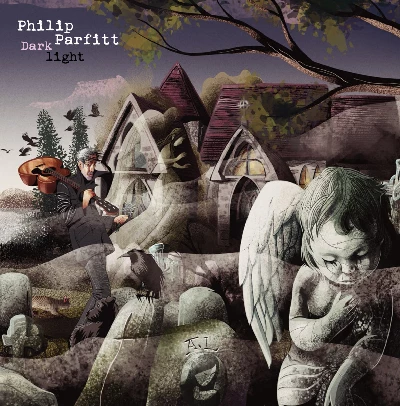

The Dark Light (2024) |

|

| Melancholic and acoustic fourth solo album from ex=Perfect Disaster frontman Philip Parfitt. |

| Mental Home Recordings (2020) |

most viewed articles

current edition

Carl Ewens - David Bowie 1964 to 1982 On Track: Every Album, Every SongArmory Show - Interview with Richard Jobson

Colin Blunstone - Thalia Hall, Chicago, 16/7/2025

Bathers - Photoscapes 1

Visor Fest - Valencia, Spain, 26/9/2025...27/9/2025

John McKay - Interview

Billie Eilish - O2 Arena, London, 10/7/2025

Robert Forster - Interview

Loft - Interview

Sir Tim Rice - Interview

previous editions

Heavenly - P.U.N.K. Girl EPManic Street Preachers - (Gig of a Lifetime) Millennium Stadium, Cardiff, December 1999

Oasis - Oasis, Earl's Court, London, 1995

Pixies - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

Beautiful South - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

Trudie Myerscough-Harris - Interview

Paul Clerehugh - Interview

Doris Brendel - Interview

Prolapse - Interview

Simon Heavisides - Destiny Stopped Screaming: The Life and Times of Adrian Borland

most viewed reviews

current edition

Phew, Erika Kobayashi,, Dieter Moebius - Radium GirlsAmy Macdonald - Is This What You've Been Waiting For?

Sick Man of Europe - The Sick Man of Europe

Davey Woodward - Mumbo in the Jumbo

Cynthia Erivo - I Forgive You

Lucy Spraggan - Other Sides of the Moon

Bush - I Beat Loneliness

Alice Cooper - The Revenge of Alice Cooper

Blueboy - 2

Suzanne Vega - Flying With Angels

Pennyblackmusic Regular Contributors

Adrian Janes

Amanda J. Window

Andrew Twambley

Anthony Dhanendran

Benjamin Howarth

Cila Warncke

Daniel Cressey

Darren Aston

Dastardly

Dave Goodwin

Denzil Watson

Dominic B. Simpson

Eoghan Lyng

Fiona Hutchings

Harry Sherriff

Helen Tipping

Jamie Rowland

John Clarkson

Julie Cruickshank

Kimberly Bright

Lisa Torem

Maarten Schiethart