Long Ryders - Interview

by John Clarkson

published: 8 / 3 / 2016

intro

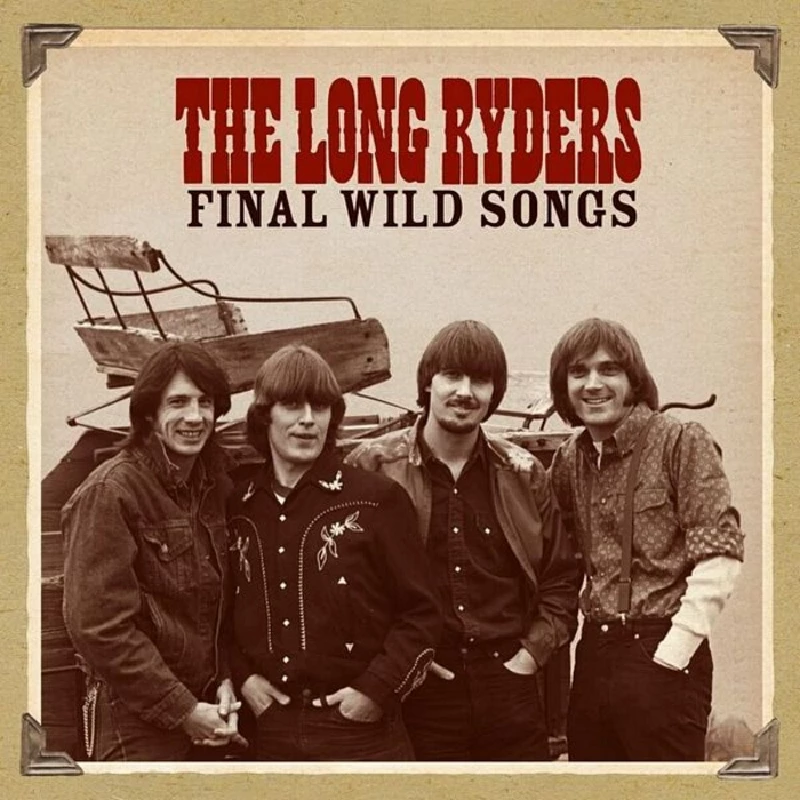

John Clarkson speaks to Sid Griffin, the front man with groundbreaking 80s band the Long Ryders, about their influence on the alt.country/Americana movement and 'Final Wild Songs', a new four CD box set

Now seen as being one of its originators, the Long Ryders lay the groundwork for much of what developed into the Americana or alternative country movement in the mid-1990s by being the first group to merge together punk and country and western influences. A part of the also influential Paisley Underground scene, the Long Ryders were formed in late 1981 in Los Angeles by the Kentucky-born Sid Griffin (guitar, harmonica, autoharp and vocals); Stephen McCarthy (lead guitar, banjo, mandolin, lap steel and vocals); Des Brewer (bass and vocals, who was replaced by Tom Stevens in 1983) and Greg Sowders (drums, percussion). Despite having a reputation for being a fiery live act and touring regularly in both America and Europe, the Long Ryders always remained a cult band, and broke up in early 1987 after failing to break through into the mainstream. A new 4 CD box set, ‘Final Wild Songs’, which has been compiled by Sid Griffin and Tom Stevens and is being released on Cherry Red Records, readdresses this and serves as a timely reminder of the Long Ryders’ influence. ‘Final Wild Songs’ contains all of the Long Ryders’ original studio recordings – ’10-5-60’, their 1983 self-released five-song debut EP; ‘Native Sons’, their 1984 first album, which came out on the durable Los Angeles-based indie label Frontier Records, and their final two albums, ‘State of Our Union’ (1985) and ‘Two-Fisted Tales’ (1987), both of which were released on Island Records. ‘Final Wild Songs’ also features various alternative mixes, live recordings and two previously lost songs. Perhaps of most interest is its fourth CD, ‘Live ‘T Beest, Goes, The Netherlands’, which, consisting of entirely unreleased material, features all fifteen songs of a particularly incendiary Dutch gig from 1985. The Long Ryders will be reuniting for some gigs this year. They will be touring Europe in late April and early May, and then America in the summer. The European dates will be their only full-length tour there since a reunion tour in 2004, and, other than one-off shows in Atlanta and Los Angeles, the American shows their first there since they split. Sid Griffin has now relocated from Los Angeles to the United Kingdom and lives in London. He fronts the acoustic bluegrass act the Coal Porters, whose sixth album is due out later this year, and is also an established music journalist and author, who has published two books on Bob Dylan, 2007’s ‘Million Dollar Bash: Bob Dylan, The Band and The Basement Tapes’ and 2010’s ‘Shelter from the Storm: Bob Dylan's Rolling Thunder Years’ . Pennyblackmusic spoke to Sid Griffin about the Long Ryders’ lasting influence and ‘Final Wild Songs’. PB: It has been almost thirty years since the Long Ryders split up. Why is this box set ‘Final Wild Songs’ coming out now? SG: I asked for the box set. Starting twenty years ago, I used to do reissues for Universal Music. For the fifteen years I worked for them I was freelance. I must have done forty packages. I said, “Can I do a Long Ryders collection?” and they would never agree to do it. The bean counter said there was not enough interest in the band , so I have been trying to have a Long Ryders collection of any sort, one CD, multiple CDs, a box set, for at least fifteen years. Two years ago a guy called Steve Hammonds at Cherry Red Records, which is associated with Universal in a loose manner, took me to lunch and said, “I think there is a market for a Long Ryders box set,” and two years later because it took us that long to do everything we have got it out. PB: What are you hoping to achieve with ‘Final Wild Songs’? SG: There are two things. I can be very specific. The second reason is not that important. I would like on a personal level a valedictory lap around the track, a lap of honour for the band. I would like to play some shows and be feted one more time by the good and the great. Obviously this box set is not going to revitalise a dead band. It is not going to change my life. We are not going to be Elvis Presley or Elvis Costello. It is going to do okay. I would like though there to be enough of a spotlight to be shown on my band and myself so that we can do some gigs, maybe get to do a TV show as well, so that we can get that valedictory lap around the track. That is what I would like. That is reason two. Reason one is that I would like it edged in marble that the Long Ryders are this important link between rock music and Americana, and that without the Long Ryders it would have been difficult to have Americana or alt.country. That is the main thing. I want the credit for that. No, we didn’t think that we were starting it, any more than the Byrds thought that they were starting folk rock or the Sex Pistols wandered around in 1976 thinking, “We are going to start a thing called punk rock.” But I want that kind of credit for the Long Ryders, that we kick-started what is called alt.country/Americana. PB: When did you first become aware that you were being seen as this groundbreaking act? SG: It was really early on. I certainly was aware of it by the time ‘Native Sons’ came out. We put out our first EP, ’10-5-60’ and the people in ‘The Gavin Report’ in San Francisco, a national radio tip sheet, really liked it. I didn’t realise at first that it meant anything. I was too young and dumb to realise that this was a national professional tip sheet which was normally worried about people like Donna Summer and Billy Joel and Survivor and all those kind of acts that were mega popular in the 1980s. I had no idea of the impact that ‘The Gavin Report’ writing about ’10-5-60’ had. Then the next time ‘The Gavin Report’ wrote about us was with ‘Native Sons’, and people were slapping me on the back in Hollywood and, as we have a multiplicity of radio stations over there, people were saying, “This is a big deal because this goes to hundreds and hundreds of different radio stations in the United States.” It was about ‘Native Sons’ that I realised that we were doing something different because we had a punk rock attitude and were hitting our instruments very hard, but we also had country and western instrumentation and that was something that had never been done before by anybody. We weren’t trying to do it to be clever. It was just naturally where we were as people. PB: You began by playing in a hardcore punk band when you first moved to Los Angeles from Kentucky, didn’t you? SG: I was in a hardcore band called Death Wish, and then I was in a band called the Unclaimed for two and half years, which was a kind of a 60s garage punk thing. They were less like the Sex Pistols and more like the Thirteenth Floor Elevators. When we started the Long Ryders in late 1981/early 1982, we were going to be some kind of Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers-type act. Then when we got in Stephen McCarthy, who is from Richmond, Virginia, he kept encouraging me to be as country and western as him. I had, however, come out of this punk scene and it was impossible for me to just dump the punk, so we mixed the two. We were a Marmite band in Los Angeles. We played gigs with people like the Circle Jerks and a lot of Southern Californian surf punk bands, and sometimes the kids would laugh when we would play a country and western shuffle. Sometimes they would spit on us, and sometimes they would dance around mockingly, and then some people would really dig it. Then a few years later all sorts of bands were doing it. One of our opening acts on one of our tours was a band called Mister Crow’s Garden. They had short hair and sounded like R.E.M. They began by playing music like that. Then these guys saw us and met a manager and became the Black Crowes, We played as well with a band in St Louis called the Primitives who were very Black Flag-orientated. It turned out that it included Jeff Tweedy and Jay Farrar and they became Uncle Tupelo. Then they went into Wilco and Son Volt and bands like that. We changed people’s minds and attitudes, and I am very, very proud of that. PB: You were part of the legendary Paisley Underground scene as well. What do you feel that the bands in the Paisley Underground had in common? If you look at its acts such as the Bangles and the Dream Syndicate and yourself, they are very different from each other. SG: Every band of the Paisley Underground loved guitars at a time of synth pop. To this day I can’t stand early and mid-80s synth pop. I didn’t like it then and I don’t like it now. I think part of the reason why I don’t like it is that those people were literally in the way, in the charts and on the TV shows, and guitar bands were considered passé. When Pete Townshend put out his solo album, ‘All the Best Cowboys Have Chinese Eyes’, in 1982, he did an interview in ‘NME’ that was reprinted in a Los Angeles magazine in which he said that guitars were obsolete and that by the year 2000 there would be no more guitars in rock. I thought, “He is nuts,” and I was right and Townshend was wrong. That was what united us. We all played electric guitars and had a certain kind of rock and roll vibe. For the Bangles that might have been the Beatles, for the Dream Syndicate it was pretty much the Velvet Underground, for the Rain Parade it was pretty much Syd Barrett crossed with the Byrds, and with Green On Red it was Neil Young and Crazy Horse. It was all based upon the guitars. PB: You have just mentioned synth pop. One of the reasons, of course, why you attracted such cult status and people liked you, especially in Britain, was that what the Long Ryders were doing was a complete counterbalance to what was going on elsewhere at the time. SG: You’re right. The reason why it went well in Britain was that we had nothing in common with Haircut 100 or Kajagoogoo or Spandau Ballet. I think that is why a lot of people there liked us, but at the same time there was nowhere to go. We did everything that we could. John Peel never played us. Towards the end of our career – I contradict myself – he played our novelty song ‘Christmas in New Zealand’, and he used to play it almost every Christmas until he died, but he never played anything but that. He told friends of mine that he didn’t like us. He thought that we were too old-fashioned, which was fair enough. It was also the same thing in the States. We had the number one college radio album and we had the number four college radio album before that, but there was nowhere else to go. There wasn’t an Americana chart. There was just a college/indie chart in America. If there had been another step on the ladder up we might have taken it, but there wasn’t one. The commercial opportunities weren’t there. PB: Was that why you ultimately broke up.? You just felt that you had gone as far as you could have possibly gone. SG: Yeah. And we toured far too much. We really hit the road. The record company also wasn’t into us. The guy at Island that signed us, Nick Stewart, was the guy that signed U2, and like idiots they let him go. So, our defender at the record label was gone. Only Andy Kershaw and Bob Harris and a few dribs and drabs played us. There was nowhere to take it. In America every town that played us on commercial radio, we would play two thousand seat venues when we played there. In other towns we would either play the college campus or the underground hipster hang outs. So, we would go from playing two thousand seats in Boston, Chicago and Atlanta where we were on commercial radio to Milwaukee where we would play to about seventy-five people. There was again nowhere else to take it. Had we been on the radio or exposed more you might be talking to a big star right now. It didn’t happen. That is just the way it is. PB: The band has sometimes been described even by yourself and your contemporaries as having “failed”. Do you think that is true? You may have never achieved that massive breakthrough or incredible record sales but, given some of the things that you did achieve, such as working with Gene Clark as you did on ‘Native Sons’ , doing all these years of non-stop touring and now being seen as this seminal act, do you think that is still really the case? SG: On a sunny day I feel that it was great. On a bad day I feel that it was a failure. I have said that it was a failure because ultimately we had a shot at the heavyweight title and we blew it. We had, to use an Englishism, a shot at winning the FA Cup and had a good team on the pitch and we were knocked out in the quarter finals, so that is one way of looking at it. When I look at the seeds which we planted I am really proud, I like it that even bands that might not have heard of us who are operating now would not have had the chance they have had if it wasn’t for the Long Ryders. We were literally the first band to mix rock and roll, punk and country and western. When I look at it that way, no, it wasn’t a failure but it was a shame we only got to plant those seeds. I would have loved to have had a proper hit record on the charts. PB: You took a lot of flak from both fans and critics when you moved from the independent label Frontier Records after ‘Native Sons’ to Island Records to make ‘State of Our Union’ and ‘Two-Fisted Tales’. Do you think that it was in hindsight the right decision to sign with Island Records? SG: Leaving Frontier Records to go to Island Records, which was a successful major with U2, Bob Marley and Tom Waits all on its roster, was perceived as a sell-out. I didn’t understand that at the time, but now I look back on it with hindsight and I can see what people were saying. It was perceived as “Who are these guys? They are grabbing at the brass ring way too soon. They obviously want money.” But there was only so much that Frontier was going to be able to do. It consisted of Lisa Fancher, the owner, and about four other people, so what was she going to do? We needed Island Records with an office in New York, an office in L.A. and London to be taken seriously. In a way I sometimes look back on it and think that was our downfall. Nick Stewart was gone within five months of us being on the label. I look back and think, “Maybe we should have stayed on Frontier for another album and cemented our indie credibility before we moved forward or just stayed on Frontier.” But you do these things in life and the chips fall where they may. That is just the way it goes. PB: You also took a lot of criticism for doing a TV advert in America for Miller Beer…. SG: Nowadays everyone - the Rolling Stones, Bob Dylan, Rod Stewart, Iggy Pop- is involved in corporate sponsorship and nobody cares, but then it was less common. There were acts like the Blasters, Los Lobos and also X, who did an advert for Budweiser’s, who were also involved at the same time as us in beer sponsorship. Ours though for some reason was something of a hit –It was on for two weeks in March 1986 in regular saturation during a basketball tournament –and we took the most criticism as a result. A lot of the indie kids of the day thought it was a complete sell-out. The reason we did the beer commercial was, however, two-fold. Only the hipsters in each town knew who we were so I thought, “If we do this beer commercial it will get us exposure,” which it certainly did. I had people who who didn’t follow rock music stopping me in the street in America and saying, “Hey, I saw you on TV. You have got a band.” It was the first that they had heard I was in the music industry, let alone the first that they had heard I was in the Long Ryders. And point two is Tom Stevens, our bass player, had already started a family. It was one thing for the three of us not to have any money, but here we had a guy who was married with a kid and we were still not making any money. We were away from home all the time, and felt that we had all paid our dues playing indie toilets. I hate to say this coldly, but to this day the only money the Long Ryders has ever seen is from that beer commercial. PB: It was you and Tom Stevens who compiled ‘Final Wild Songs’. SG: It was mainly Tom, to be honest. I just vetted it. Every band has one guy who is an archivist, and Tom is our guy. He is a huge archivist. The Rolling Stones, for example, had Bill Wyman. Bill Wyman kept a diary and had all these set-lists, and Bill can tell you where the Rolling Stones were on, say, June 4th of 1966. He has got it all written down, and Tom is like our Bill Wyman. He has all these things written to hand. In fact Tom kept live tapes and stuff from before he was in the band. We existed for a year and three quarters before he joined the band after the ’10-5-60’ EP. PB: As well as ’10-5-60’, the three albums and various alternative mixes and other live tracks, the fourth CD on ‘Final Wild Songs’ is given over to a previously unreleased live gig that was recorded in the Netherlands in 1985. Why did you choose to put that particular gig on the box set? SG: Tom found it. We wanted to have something on there that showcased that we were a great live band, and Tom said, “Speak of the devil! I have just found this live recording!” I had forgotten all about it, but I remember it now because when we got there this incredible burst of feedback came through the monitors while were setting up and almost made us all deaf, which Tom alludes to during the liner notes. There are three things that I like about this live recording. Firstly the band is absolutely on fire. We are tearing the roof off the place. There is not much editing on it. We are just exactly as we sounded that night. Apart from the great performance, the second thing that I like about it is that it is very well recorded, and the third thing I like about it is that it doesn’t have the same old songs. For instance, ‘Looking for Lewis and Clark’ hadn’t even been written yet. We have had two previous live albums out. One was a bootleg, ‘Three Minute Warning: Live in New York City’, which came out on Prima Records which specialises in reissues. Then we put out a live album from our 2004 reunion tour, ‘State of Our Reunion’, which again came out on Prima, and now we have got a third live album out which has both this well-recorded blistering performance and different songs on it. PB: You are going to be touring Europe for the first time since 2004 in late April and early May. Which countries are you going to be playing? SG: We have Spain booked for the last week of April, and the UK for the very first week of May. We will be playing shows then in London, Brighton Brighton, Leeds, Manchester and also Dublin. We wanted to play Scandinavia and Italy as well but there just isn’t time. We only have two weeks because Greg Sowders, our drummer, is the Vice-President of Warner Chappell Song Publishing in L.A. It is a big deal. They are the people who won the copyright to ‘Happy Birthday‘, so he has got a real job getting songs onto Hollywood movies and into TV shows. We are only, therefore, going to have two weeks to tour Europe (Laughs). Then in the summer we are going to be doing an East Coast of America tour followed by a West Coast tour, the first in July and the other in August. Since the Long Ryders broke up, we have done two shows in Atlanta and one in Los Angeles and that is it. We have done three American concerts in twenty-nine years, so we haven’t played New York or San Francisco or Chicago since 1987. My friend in Los Angeles went to see Graham Parker and the Rumour when they played there after they had got back together, and the exact same people were in the room that were there in April 1979 when Graham Parker played his last gig in Los Angeles in the exact same room (Laughs), but that is fine with me. I will be thrilled to go to San Francisco, to go to Chicago and to Boston where we did very well and New York and to see so many of these old fans. That is what I want. PB: Thank you.

Band Links:-

http://www.sidgriffin.com/long-ryders/https://www.facebook.com/The-Long-Ryders-206678626039432/

https://twitter.com/longryders

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Long_Ryders

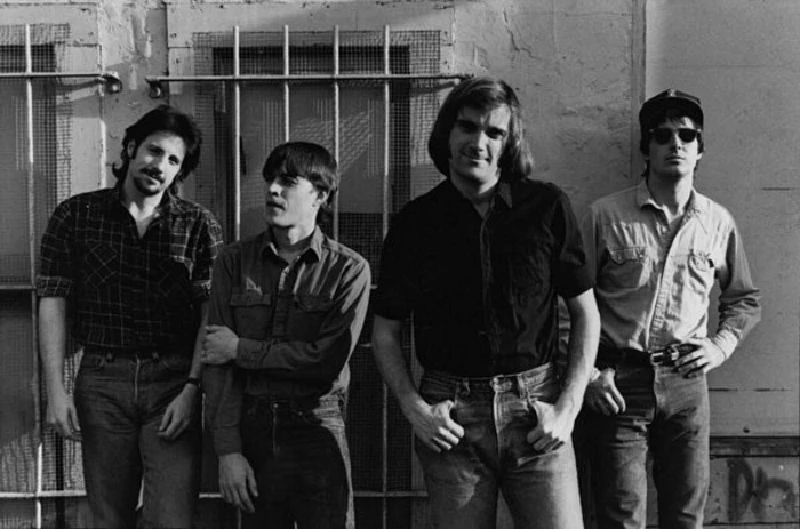

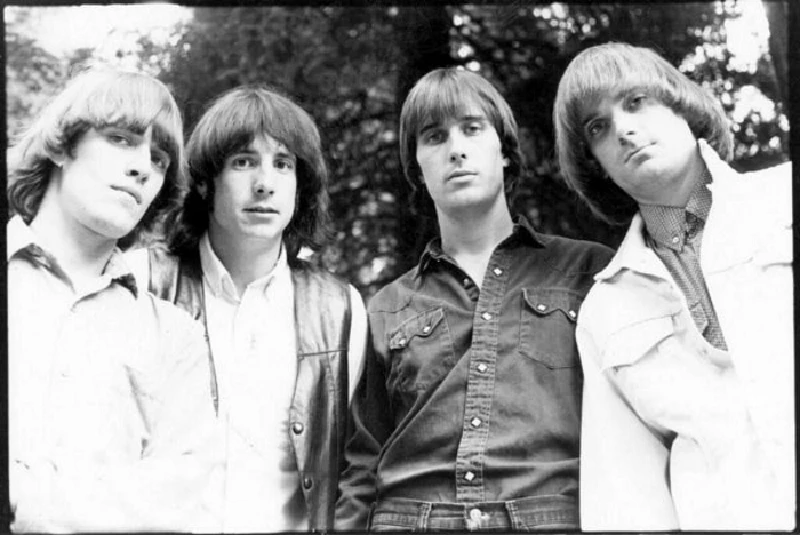

Picture Gallery:-

interviews |

|

Interview (2019) |

|

| John Clarkson talks to Sid Griffin, the frontman in groundbreaking Americana outfit the Long Ryders, about 'Psychedelic Country Soul', their first studio album in thirty-two years. |

photography |

|

Photoscapes (2023) |

|

| Philamonjaro photographs pioneering alt.country group The Long Ryders at The Loco Club in Valencia in Spain. |

most viewed articles

current edition

John McKay - InterviewRobert Forster - Interview

Cathode Ray - Interview

Spear Of Destiny - Interview

Fiona Hutchings - Interview

When Rivers Meet - Waterfront, Norwich, 29/5/2025

Carl Ewens - David Bowie 1964 to 1982 On Track: Every Album, Every Song

Chris Wade - Interview

Brian Wilson - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

Shrag - Huw Stephens Session 08.12.10 and Marc Riley Session 21.03.12

previous editions

Heavenly - P.U.N.K. Girl EPBoomtown Rats - Ten Songs That Made Me Love....

Allan Clarke - Interview

Oasis - Oasis, Earl's Court, London, 1995

Manic Street Preachers - (Gig of a Lifetime) Millennium Stadium, Cardiff, December 1999

Barrie Barlow - Interview

Pixies - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

Beautiful South - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

Trudie Myerscough-Harris - Interview

Dwina Gibb - Interview

most viewed reviews

current edition

Peter Doolan - I Am a Tree Rooted to the Spot and a Snake Moves Around Me,in a CircleGarbage - Let All That We Imagine Be The Light

Vinny Peculiar - Things Too Long Left Unsaid

Vultures - Liz Kershaw Session 16.06.88

John McKay - Sixes and #Sevens

Little Simz - Lotus

HAIM - I Quit

Morcheeba - Escape The Chaos

Pulp - More

Lapsley - I'm a Hurricane, I'm a Woman In Love

Pennyblackmusic Regular Contributors

Adrian Janes

Amanda J. Window

Andrew Twambley

Anthony Dhanendran

Benjamin Howarth

Cila Warncke

Daniel Cressey

Darren Aston

Dastardly

Dave Goodwin

Denzil Watson

Dominic B. Simpson

Eoghan Lyng

Fiona Hutchings

Harry Sherriff

Helen Tipping

Jamie Rowland

John Clarkson

Julie Cruickshank

Kimberly Bright

Lisa Torem

Maarten Schiethart