Suzanne Vega - Interview

by Lisa Torem

published: 13 / 3 / 2012

intro

Lisa Torem chats to bestselling singer-songwriter Suzanne Vega about her inspirations, love of New York and support of human rights causes.

Suzanne Vega’s creativity started early. At nine she wrote poetry and as a teen dancer she attended the High School of Performing Arts (which ‘Fame’ was based on). The oldest of four, the reserved singer-songwriter grew up in a tough New York urban climate, although she eventually found acclaim playing Greenwich Village venues as she surrounded herself with other emerging writers. Her self-titled 1984 debut attained platinum status in the UK. ‘Luka’ and ‘Tom’s Diner’ remain from ‘Solitude Standing’, her 1987 second album, two of her most well known and commercially successfully hits, but thereafter Vega went on to court a variety of producers. She took risks with ‘her 1992 album, ‘99.9F’ which featured industrial beats (a far cry from her acoustic leanings) and was produced by Mitchell Froom who became her first husband. 2001’s ‘Songs in Red and Gray’ examined loss and heartache, while 2007’s ‘Beauty & Crime’ celebrated style and nostalgia, ‘Tom’s Diner’, which Vega wrote to be sung a cappella was picked up by British artists, DNA. With Vega’s endorsement, this version became another commercial success. That she’s been referred to, as a “female Nick Drake” sounds a bit unfair. That’s like calling Bob Dylan a male Joni Mitchell. Truthfully, Suzanne Vega’s writing is as penetrating and socially profound as that of her peers, both male and female, living or dead. Her themes span vintage characters plastered to her wall as well as songs of romance, isolation, abandonment and abuse. Suzanne Vega spoke to Pennyblackmusic about her early inspirations, infatuation with New York and continued commitment to human rights. PB: ‘New York is a Woman’ from ‘Beauty & Crime’ is such a powerful song. Why has the city of New York had such a powerful affect on your songwriting? SV: Because I live there and have lived there for more than fifty years at this point, and it’s a city that I’m deeply involved in. It’s impossible to live there and not be deeply involved in it, because it’s a city with such a strong character, and, also, my own life in living in New York – I’ve lived in some of the worst neighborhoods and then also I’ve experienced huge success here, so it’s a city that accommodates all of that life. You can see the worst kind of poverty there, and, also if you have money, you can enjoy all of the amazing luxuries that New York can provide. It really has this swing to it. PB: ‘Tom’s Diner’ was set in Manhattan. Was that really important or could it have been set in any US diner? SV: It probably could be anywhere – the sense of alienation. A diner is a funny thing. It’s kind of a midway point between being home and being out in the street. You can either feel a sense of community there with other people or you could feel alienated, so it probably could have taken place any place where there is a diner. PB: You found out that the man, who you thought was your biological father was your stepfather at the age of nine. So how did that event affect your position in the family or even your songwriting? SV: I wouldn’t say that directly influenced my songwriting, probably the fact that I was someone else’s’ child influenced it in that I always had a bit of a feeling of being an outsider, and I think that has informed my songwriting. PB: ‘Luka’ was a nine-year-old boy. Was there a connection there? SV: Hmm. Not consciously, no, but, the kid who I based it on was about nine. It’s one of those funny ages. PB: You have worked with a human rights group, Casa Alianza. Was that as a result of recording ‘Luka’, which is about an abused child, or has that theme always been very important to you? SV: The theme of human rights has always been important to me even before I ever heard the word coined. And then there was a man, Fred Shortland, who came to me one day, he was working with Casa Alianza, the local charity, from England, and he asked me if I wanted to get involved with children’s’ rights and I thought that was a natural fit, and I think he approached me because of the song. PB; You had to make choices when writing ‘Luka’ that it would be sung from a child’s viewpoint and, consequently, it is such an unpretentious song. How did you achieve that balance? SV: First of all, when I wrote the song I had no expectation of having any kind of audience, or a very small one. Child abuse is not something people like to hear about or talk about, so I wrote it because I wanted to write the song, but I wasn’t writing it to make a statement, I was writing it to express that point of view. So I decided to make it as simple as possible and as truthful as possible; just strip away anything that didn’t need to be said, and I wanted to do it in the way a child would do it. I think that’s what eventually happened. I think, in the three or four verses that I got down there, I managed to get the problem, which is that you have a problem, but you can’t say it, but it still exists. In a sense I’m blaming the neighbour – there is a neighbour involved – Luka is talking to a neighbour, so there’s that implication that if you hear something… but that doesn’t do anything. PB: Do you feel protective over this song? SV: I do watch over it. It depends what people want to use it for. People have used it for domestic violence, PDAs and I’ll allow it for that purpose, but, if someone wants to use it for some other reason, I would just suggest that there’s probably a better song. PB: You once worked with composer Philip Glass on a project on which he selected only a handful of songwriters, ‘Songs from Liquid Days’. SV: We’ve worked together many times. PB: And what attracted you two to each other musically? SV: I don’t know what attracted him, but I know, for myself, that I love his music and I feel a deep connection to how he makes his music. I love the repetitions in his work and I find a lot of his compositions very moving, very emotional, so I’m always happy to work with him. I love a lot of his music. My favorite piece is probably ‘Mishima’. But I’ve heard other pieces too that move me to tears and I don’t know what they are – I have to find out because he’s so prolific. It’s hard to tell which piece is the most current one. PB: There’s an underlying drone is his pieces, which is present in your guitar playing too. SV: Yeah, I would agree with that. I was there when he gave a little interview to a friend of my daughter’s, who is a big fan of Philip Glass. She asked him what had influenced his music and he said it was either Indian music or African music. I think he went to India and studied Indian music, so you can find a sense of that there. There’s spirituality to it and a sense of repetition to it – figures that to me sound kind of madras like, that I really like. PB: You’re not that concerned with beginning, middle and ends when you write a song. Is that true? SV: It depends on the song. There are some songs that have very, clearly defined beginnings, middles and ends. ‘The Queen and the Soldier’ from my debut album definitely has a beginning, middle and end, but, musically, I’d say it’s more circular, I suppose. Maybe that’s what you mean. I do like the idea of a circle. It’s my natural way of doing things (Laughs). But I do feel that sometimes I have to work on getting a melody to have more of a beginning, middle and end. My natural sense of things is a circle. PB: You mention a man, Kasper Hauser, on your site, whose language abilities were affected by his unorthodox upbringing. Was your song ‘Language’ from ‘Solitude Standing’ written about him? SV: No, ‘Language’ was written from my own point of view. I didn’t speak myself until later on – very much, until I was about two and a half. PB; You actually remember not speaking? SV: No, not at all. My mother mentioned it. She said she was relieved when I started to read when I was about three, because before that they thought I was a little slow in the head. (Laughs) PB: Maybe you were just the intelligent observer. SV: Yes, there was a lot to see and those were the years when we had moved from California to New York, so there was a lot to take in. There was a lot going on and I probably didn’t have a lot to say, so anyway I’ve always found language to be especially in emotional moments very difficult, something that I have to sit and work with. Very often I can’t say anything or there’s nothing that occurs to me. So it was really my own perspective. I wasn’t connecting it with Kasper Hauser, but I think you’re probably right. Kasper Hauser did have trouble speaking. He could only repeat a few phrases over and over again. PB: How do you see the relationship between poetry and songwriting? SV: Well, poetry is a funny thing. Poetry can exist on the page very happily. It doesn’t always need to be read out loud – or spoken, and there are kinds of poems that are great in both places: great on the page and also great when spoken. A song is really its own thing. You can have a song that is a great song and looks absolutely stupid on the page. You can sing something and it will have conviction and meaning in it and it will be great, and it just won’t be poetry. On the other hand you can have poems that are great poems and, if you try to sing them, you feel like an idiot and probably look like one too. There’s a funny line between the two things and, to me, it all comes down to can this thing be sung or not? Can you sing it convincingly or not? PB; Is there a relationship between ‘Small Blue Thing’ from your debut and a certain type of spirituality, or should we take it more literally? SV:I hadn’t meant it that way. I wrote it so long ago, I’m wondering what that mood actually was, but I was more trying to convey a sense of sensuality, I suppose, which can be intertwined with spirituality. For some people and for me that’s definitely true. So there’s kind of a borderline, I guess. For me that wasn’t specifically what I was going for, but I would say it is expressed in it. PB: Is that song coming from the same place as when you write about an invented character? SV: Sort of, I guess, in that I’m trying to express an image or an idea. It’s not just a feeling. There’s something behind it that I’m trying to express. A character is more specific obviously. I would try to find out what language that character would use, how old is that character, is it male or female? Whereas a song like ‘Small Blue Thing’ is more abstract. If I were an animation, or a cartoon, how would that feel? PB; Did you start with the guitar part or the imagery? SV: Probably the imagery and I probably had the guitar part worked out before. I tried to find something that would match that mood. PB: How did you learn to play the guitar? SV: I learned guitar by playing chords that I liked. I had this book that had all of these chords written out. It was called ‘The Pop Hits of the 60s’, I think. PB: Sounds like fun. SV: Yeah, it was, and it had little pictures of where you put your fingers on the guitar to make certain sounds and I discovered which chords I loved and stayed away from the ones I hated, and I may have invented a little vocabulary to speak with. I tried to take lessons and I found that really frustrating. I wasn’t one of those kids who could actually play things that they heard on records. From time to time, I would play, as a folk singer, when I was in camp, when I was teaching in sleep away camp, but I’m not one of those people who could pick up a song and learn it. It was more a private language that I taught myself from this book. PB: ‘Calypso’ from ‘Solitude Standing’ had a fascinating point of view. When you read literature, do you think, “That story will make a great song?” How did you arrive at that perspective? SV: Well, I’ll tell you a rather personal story. It was my first year in college and I was taking this Humanities course, and one of the first things we had to read was Homer’s ‘The Odyssey’ and I remember being struck by the whole situation. I had a boyfriend at the time that would call me ‘Circe’ as a nickname to annoy me, and it did annoy me. And I don’t feel I’m like Circe, I’m not turning anybody into swine. If I’m like any goddess around here, I suppose I’m more like Calypso, because he was always leaving. So that’s what goaded me into writing the song (Laughs). PB: It’s very relevant. It reminds me of a girl supporting her husband through medical school and then he leaves her for the neighbour. It has that contemporary feel to it, alhough it was inspired from so long ago. SV: Yeah, I felt for her. She was there. She nurtured him. He landed there shipwrecked and all he could think about was his wife back home. So I’ve had people write to me and say, “So what about Penelope?” That’s not as interesting to me as Calypso. And it would be interesting to write a song from ‘Circe’s’ point of view, too. What is her motivation? PB: You’ve used a variety of producers in your career. When you look back, were you happy with your choices? Were you influenced in the right directions? SV: Essentially, yes. I’ve been happy with all of the producers that I’ve worked with. I’ve learned the most from Mitchell (Froom) and he was the most challenging, also because there were moments when I didn’t always agree with what he said and so I would say, “That’s not appropriate or I don’t want to do that,” and he was fine. He had a great imagination. He brought everything to the table when he worked, so if I hated something he would immediately give it up. He wasn’t someone who defended his own point of view or inflicted his own methods, but it wasn’t always easy. It wasn’t always natural, but a lot of it was and I learned so much about music and about production, things that I’m still teaching my daughter today. And the other producers did a good job. I think Steve (Addabbo) and Lenny (Kaye) who did both ‘Suzanne Vega’ and ‘Solitude Standing’ together were inexperienced. We were all sort of hashing it out in the studio, so when I listen to those records, even though they were the most successful ones, I’m not always that happy with how they all came out. When I did the third album, ‘Days of Open Hand’, in 1990 I worked with Anton Sanko, and that was extremely difficult trying to do that myself with Anton and I find that’s probably the one I don’t listen to. Anton and I were living together and working on the album together, and I had just had this huge success with ‘Solitude Standing’, and there was a lot of pressure, and I just found that I didn’t want to be there. A lot of times I would just go out for a walk or do anything just to avoid doing my vocals, and there was no other place to go. I decided after that I was never going to work out of my house again. There was no place to hide, no place to go, and half the time I’d end up cooking for people. I just thought, no, no, no and when I listen back to it I hear the strain that we were under. The songs were good, but I think the production was stilted in some way, not through any fault of our own; it was just the stress of the situation. And the other producers, which were Jimmy Hogarth who did ‘Beauty & Crime’ and Rupert Hine who did ‘Songs in Red and Grey’ were very talented but Mitchell set the benchmark or watermark. He set the high watermark (Laughs). So I think we were always trying to achieve the sense of immediacy that Mitchell had done. I love though what Rupert Hine did. He was very talented and a really great producer in his own right, but we always had the shadow of Mitchell to contend with. PB ‘99.9F’ was a departure from your previous styles. Were you excited about that change? SV: I was very happy going in that direction. Mitchell and I worked on that album so quickly and we came up with all of the ideas and the sketches in about two weeks. It was a very quick process and we were both in the same state of mind. I loved everything about that album. It really surpassed all of my wildest dreams. PB: You were very influenced by Leonard Cohen and then one day he interviewed you. What was that experience like? SV: It was great. It was very funny. He had been corralled by A & M Records to come in and do this. It was a really great idea. I thought it was so great, and I guess he’d had a bit of wine and we’d been in the room together for about an hour, and it was a very funny occasion and I enjoyed it very much. PB: Was it a bit surrealistic? He was one of your heroes and then he was interviewing you about your music. SV: It was surrealistic because he had been drinking and I hadn’t been, and some of this was a performance on his part for the microphone. His manner changed considerably -- we went out to dinner afterwards and all of those probing questions stopped. So some of this was a bit of a performance on his part. But I had met him a few times before that. I met him for a Rolling Stones shoot where we were supposed to choose our mentors, and Lou Reed was not available, and I chose Leonard Cohen. The pictures were beautiful and that was even more surreal because the photographer had me with my head against his chest and my head in his hands, and my ear for a while was mashed against his chest, and I could hear his heart beating and I had to complain. I didn’t say we were lovers. He was supposed to be my mentor. She had him put my head in his hands and those pictures are very interesting. You can find them on the internet. PB: You opened for Janis Ian. Was she an influence in your writing? SV: No, I admire her and I loved her guitar playing, and I still think she’s a terrific, talented writer, and if you’ve ever seen the first ‘Saturday Night Live’ she was a special guest. Her playing is so poised, but I wouldn’t say she’s a big influence. I listened to her for a while and I admired it, but I wouldn’t say I really took it in like Laura Nyro. PB; Laura Nyro? SV: Laura Nyro was like a sister figure to me. I was really obsessed with her. I felt closeness to Laura Nyro that I never quite achieved with Janis Ian, but I admired her. PB: What songs of Laura Nyro’s did you admire? SV: The first three albums. Everything from the first song to ‘Eli and the Thirteenth Confession’, ‘New York Tenderberry’, I wouldn’t say she influenced me because first of all she played the piano, but I loved the way she thought and I love the way that came out in the songs. I loved her inconsistencies and the characters she wrote about. She always wrote about boys named Joe or Tom. I know boys like that. I went to school with them. They were really kids I knew too. So I really loved her for that and I just loved here for who she was. PB: She was a very natural performer, and I think people think that way about you as well. SV: Well, in some ways she was very dramatic too. She had the long hair. She was very feminine, very female, whereas I didn’t feel very female. I was a more boyish kind of girl. I thought of her as the womanly figure that I would never be. But she wrote about New York and she wrote about sexuality and being a teenage girl and all of the dangers that that implied, as well as the thrills, and for that I was grateful. PB: That dichotomy shows through in a lot of your lyrics, too. It makes the songs very accessible. If you took your 1996 album, ‘Nine Objects of Desire’, would you feel a need to update that list or would they remain the same? SV: Neither. They wouldn’t be the same, nor would I feel the need to update them. I felt that that was like a moment in time and that when I look back at that collection of songs, that the thread between all of them was that sense of desire. Obviously it’s different now. My daughter’s older. I have a different husband, so some things are different now, but I don’t know. I haven’t catalogued them lately (Laughs). I can’t tell you what they are. PB; Do you see yourself in your songs: ‘Gypsy’ or ‘Marlene on the Wall” from the first two albums or even ‘Edith Wharton’s Figurines’ from ‘Beauty & Crime’? SV: Yes. ‘Gypsy’ was a sincere love song to a man that I was involved with. I still feel myself to be the narrator of that song. ‘Marlene on the Wall’ – yes, the point of view is Marlene’s image – watching the girl I once was in my room. But I still feel it when I sing the lines, “I think it’s called my destiny that I’m changing.” I still feel that. There are moments in that song that are timeless. PB: You have done a lot of touring with Duncan Sheik. Do you have more plans to tour with Duncan Sheik? SV: I toured with Duncan two years ago and we are going to do another run of shows together. He’s great and I’ve known him for a long time. I knew him way before he made his first album. He’s a Buddhist and I’m also a Buddhist. He used to practice Buddhism with the same group that my mother did, and so I remember him opening for me way back in 1995. So we’re chums and we’re also working together on the Carson McCullers Theatre Project. I’m so happy with those songs and from time to time I think we’ll go on the road together. PB: So this is a musical that you’ve been working on together? SV: Yes. It came out last year. It was produced by the Rattlestick Theater and it ran for five weeks. He was the composer and I was the lyricist and I also played the lead. I played Carson McCullers in the lead role. PB: And you enjoyed that process? SV: Yes, it was a whole new world for me. I had studied acting and theatre when I was in college, but doing it for real was a whole different experience. I wasn’t happy with how it all ended. Even today – I’m rewriting the book. I’m happy with the music, but not with the book. So I’m still working on it and tweaking it and making it do what I want it to do. So it will be remounted this fall. PB; Do you plan to write your autobiography? SV: I would love to write my autobiography one of these days when I have enough time to stay home and actually work on it. It’s not something you can do in between other projects, so, yes, in the next couple of years I’d love to do that. PB: Do you have any additional touring plans? SV: I’m always touring. I do about fifty shows a year, and I usually spend about five of those weeks in Europe, and other places. I just came back from Asia and that was great. I like the touring life. It’s how I make my living for the most part. I’m really enjoying it. Your readers should check out ‘The Close-Up’ series. For ‘The Close-Up ‘series, I’ve been rerecording my back catalogue and putting them out on my own record label. So they’re kind of reinterpretations of my old songs and I’ve put them together by themes, instead of by albums. All the love songs are on one album; all the freaky weird songs about states of being are on one album and then the hits, which I call, “People and Places’, are on another album. Die-hard fans can check them out. You can either get them through Amazon, iTunes or my website. PB: Thank you. Suzanne Vega is currently taking part in a world tour, which will conclude in the United Kingdom in June with dates in London (Union Chapel, 13th June), Brighton (Dome, 14th June), Glasgow (Oran Mor, 18th June), Gateshead (Sage, 19th June), York (Grand Opera House, 20th June) and Basingstoke (Anvil, 21st June). Tickets can be bought from the usual agencies and also at the venues

Band Links:-

https://www.suzannevega.comhttps://www.facebook.com/SuzanneVega

https://www.instagram.com/therealsuzannevega/

Have a Listen:-

Picture Gallery:-

Visitor Comments:- |

| 553 Posted By: Myshkin, London on 17 Apr 2012 |

|

Ever get the feeling that Ms Vega fancies herself as some great auteur? And when exactly was the last time she had anything important to say?

|

interviews |

|

Interview (2016) |

|

| Lisa Torem talks to New York singer-songwriter Suzanne Vega about author Carson McCullers, the new album which she inspired and her upcoming tour |

| Interview (2015) |

| Interview (2014) |

live reviews |

|

Old Town School of Folk Music, Chicago, 1/5/2022 |

|

| Lisa Torem enjoys Suzanne Vega's much-awaited set at Chicago's Old Town School. which includes hits and selections from her one-woman show about novelist Carson McCullers. |

| S.P.A.C.E., Evanston, Illinois, 22/2/2013 |

soundcloud

reviews |

|

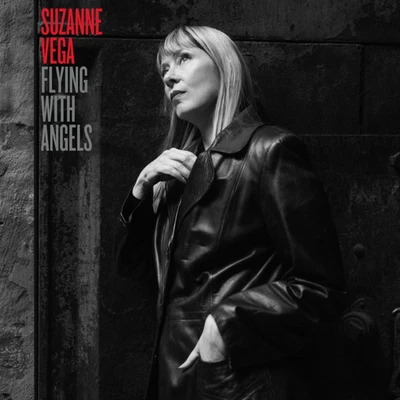

Flying With Angels (2025) |

|

| Outstanding first album in nine years from Suzanne Vega which breaks new ground |

| Lover, Beloved: Songs from an Evening with Carson McCullers (2016) |

| Close-Up, Vol. 1-Love Songs (2010) |

most viewed articles

current edition

John McKay - InterviewCathode Ray - Interview

Robert Forster - Interview

When Rivers Meet - Waterfront, Norwich, 29/5/2025

Spear Of Destiny - Interview

Fiona Hutchings - Interview

Carl Ewens - David Bowie 1964 to 1982 On Track: Every Album, Every Song

Chris Wade - Interview

Shrag - Huw Stephens Session 08.12.10 and Marc Riley Session 21.03.12

Brian Wilson - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

previous editions

Heavenly - P.U.N.K. Girl EPBoomtown Rats - Ten Songs That Made Me Love....

Manic Street Preachers - (Gig of a Lifetime) Millennium Stadium, Cardiff, December 1999

Allan Clarke - Interview

Oasis - Oasis, Earl's Court, London, 1995

Barrie Barlow - Interview

Beautiful South - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

Pixies - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

Chuck Prophet - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

Dwina Gibb - Interview

most viewed reviews

current edition

Peter Doolan - I Am a Tree Rooted to the Spot and a Snake Moves Around Me,in a CircleVinny Peculiar - Things Too Long Left Unsaid

Garbage - Let All That We Imagine Be The Light

Vultures - Liz Kershaw Session 16.06.88

John McKay - Sixes and #Sevens

Little Simz - Lotus

HAIM - I Quit

Pulp - More

Lapsley - I'm a Hurricane, I'm a Woman In Love

Billy Nomates - Metalhorse

Pennyblackmusic Regular Contributors

Adrian Janes

Amanda J. Window

Andrew Twambley

Anthony Dhanendran

Benjamin Howarth

Cila Warncke

Daniel Cressey

Darren Aston

Dastardly

Dave Goodwin

Denzil Watson

Dominic B. Simpson

Eoghan Lyng

Fiona Hutchings

Harry Sherriff

Helen Tipping

Jamie Rowland

John Clarkson

Julie Cruickshank

Kimberly Bright

Lisa Torem

Maarten Schiethart