Kinks - Interview With Mick Avory

by Lisa Torem

published: 20 / 3 / 2011

intro

With their first three albums having just been re-released in expanded double CD editions, Mick Avory, the drummer with the Kinks from the early 1960's until 1984, speaks about his years with the band and their continuing influence

Drummer Mick Avory’s humble telephone voice gives away none of the dramatic, craggy climb to success that British Invasion rock group, the Kinks, survived. Avory, who was rumoured to have performed with the Rolling Stones, but actually simply rehearsed with their initial line up in 1962, went from supporting percussionist, when session musicians performed on the band’s first recording, to an unassuming, but all around instrumentalist, unrivalled during the recordings of albums such as ‘Kinda Kinks‘ (1965) and ‘The Village Green Preservation Society’ (1968). Avory, who left the group in 1984, also afterwards managed the Kinks’ recording studio, Konk, and, though he and guitarist Dave Davies had endured battles which lead to him leaving the band, later contributed to ‘Rock ‘N’ Roll Cities’, a track that Dave had written for the Kinks’ 1986 album, ‘Think Visual’. First called, the Ravens, the group was started by guitarists Ray Davies and his younger brother, Dave. The two Muswell Hill Londoners, soon added guitarist turned bassist Peter Quaife to their skiffle contingent. By 1963 they discovered their songs required a hefty back beat. First drummer, Mickey Willet was chosen and replaced by Avory shortly before the group signed to record label Pye. The climb, still in its wobbly form, warranted a cover of Little Richard’s ‘Long Tall Sally’ which, sadly, did not chart. It was not until their third original, ‘You Really Got Me’ with, at its core, the younger Davies’ distorted, contagious guitar riff, and scratchy vocals via big brother Ray that they struck gold. Within a month, the American public also enjoyed the number one hit. Quickly following was ‘All Day and All of the Night’, the group’s fourth single, in 1964, which reached number seven in the US and two in the UK. Frenetic touring to support this unprecedented style meant tensions were high between members at performances. There were the internal squirmishes between the brothers, themselves, and also between Dave and Mick, which even resulted in physical assault. After their summer tour ended in 1964, their ambitious touring was cut off by American unions. Some say this action allowed the band to look inward and celebrate their British culture, though; it also meant they bypassed the zenith of the American youth movement, including Woodstock. Consequently sonic pictures of the English countryside and ordinary London sightlines found themselves immortalized in song. ‘The Kinks Kontroversy' featured the sardonic ‘Sunny Afternoon’ exploding in popularity in the UK in 1966, at the number one spot. 1967’s ‘Waterloo Sunset’ was another contagious, melodic ballad that demonstrated the transitory songwriting the group had instigated. By 1969 Pete Quaife, who died in 2010, had left and was replaced by John Dalton. After creating the album ‘Arthur’ keyboardist John Gosling was added and enjoyed his premier in ‘Lola’ – a song, ahead of its time, which explored transexuality. The band’s climb escalated once more in both countries and were now allowed back into the US. Jim Rodford on bass and Gordon Edwards were now members. Meanwhile, punk groups such as the Pretenders and the Jam were covering Kinks material and the band was invited to play huge arenas. ‘Low Budget’(1979) and ‘Give the People What They Want’ (1981) were two albums which recaptured their legacy. In 1983, ‘Come Dancing’, an astounding number that somehow mixes a mariachi-like charm with a black and white film noir shroud, became an American MTV hit. Avory was first inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1990 and the UK Music Hall of Fame in 2005, with Pete Quaife and the Davies brothers. Avory, since leaving the Kinks, has performed with the Kast Off Kinks, the Class of ’64 and Shut up Frank. Ray Davies will be curating the annual Meltdown Festival In London in June and to commemorate this the Kinks have just reissued their first three albums, ‘The Kinks’ (1964), ‘Kinda Kinks’ (1965) and ‘The Kinks Kontroversy’ (1965), in double CD format. The albums have received the royal treatment, as they are presented along with session out takes, liner notes which chronicle the album’s development, Ray Davies’ BBC interviews, covers such as Bo Diddley’s ‘Cadillac’ and, of course, hits such as ‘You Really Got Me.’ The project provides alternate and demo tracks as well. Mick Avory remembers better, of course, how, as a young man, he got entangled with two brothers from a musical family, and forged one of the most influential, but possibly under-appreciated rock bands of this century. PB: Let’s talk first about the reissues. You had a song called, ‘Long Tall Shorty’ on the first album. I know you were a fan of the Graham Bond Organisation and I wanted to know how you chose the covers for this album and whether you were influenced by their drummer, Ginger Baker, as I know you both were appreciators of jazz? MA: I’m not really, as Ginger Baker has had a different approach, even though we both came from a jazzy background; these long solos with two bass drums, soloist, sort of a virtuoso. I was more like Charlie Watts I’ve been told, and we both come from similar backgrounds, you could say. I’ve played with a couple of people he has played with, namely Brian Knight, who is an old blues guy that he has played with, a blues guy that Charlie used to work with, when I first came across the Kinks and they were playing a lot of blues; back in those days they were like a rhythm and blues band. It was before they got their own sounds and their own songs. That’s what their roots were and they used to try a lot of Chuck Berry stuff and Lil’ Benny, Lightning Hopkins and all those old blues people, Big Bill Broonzy, who I used to like, and out of that they began to get their own style. So, that was like the beginning. ‘Long Tall Shorty’ – I’m not sure who did that, can’t remember…I don’t know who actually recorded it or wrote it. PB: It was written by Don Covoy and Herb Abramson, president of Atlantic Records at that time. It was also the Graham Bond Organisation’s first single… MA: Yeah. Whatever, quite popular songs to do at that time. PB: ‘You Really Got Me’ was a huge hit. How did you see your role in that song in terms of being a drummer? MA: It was actually a riff, so you couldn’t really do a lot with it. You know, you play the riff because it happens all the way through. You play the riff with the bass drum, ‘BAH BAH BAH BAH BAH BAP, BAH BAH BAH BAH BAH…’and, then the bass drum and snare. You’re really confined to doing that. If you did anything else, it would just confuse it. PB: Do you remember the day you first heard the tune? MA: It was mainly Ray and Dave that sorted it out. Ray wrote the song and Dave put the sound to it. But, it was different and they toughened it up, and that was the beginning of it. We used to play it on stage and then we decided to record it. PB: For the album, ‘Kinda Kinks’ you guys had just finished touring the US. and didn’t have a lot of time to get it together. (The album contained twelve tracks, ten were original).Was that a curse or a blessing? The album had a very natural, raw sound. MA: What happened is we went to America in 1965 and we had had two or three hits in America, consecutively, so it was all happening quick when it happened so they got us over there and everything was rushed. We were rushing around and we weren’t really prepared for it, you know. That wasn’t to be because we upset the unions; there was a purge on the bands coming over and doing this and that, and we couldn’t do TV, and did a couple of shows we shouldn’t have done on TV, and consequently got banned and we couldn’t go back for three years and couldn’t go back until 1969. We had a bit of a pause from America. PB: What was the actual cause of the American Federation of Musician’s ban? MA: They stopped people working from these places, because the unions run all these places. They stopped the work; they’re not supposed to operate. And, if you transgress these union rules, they get in trouble and so do the people who do the work. It all ended up like that suddenly. PB: It was not because they considered the material controversial or because of the onstage performance… MA: It was nothing to do with the material. They wouldn’t know what you were doing anyway… (Laughs). PB: Do you feel that that experience prompted you to be more who you were though? I mean, ultimately, the Americans loved that you broadcast such a British feel. You weren’t trying to imitate the American sound. That was really clear. MA: Yeah. PB: Was that a good thing, ultimately? MA: Oh yeah. The Americans – they loved the English accent, anyway. Anything English went down well. When Ray was writing about some English nostalgia, it went down doubly well, because it was so English and it was like a lot of bands were derivative of American bands or something that happened in America or old blues guys or something… But, we sort of got a direction that was really different. Ray got to writing a bit and most of the songs were about old England and nostalgia and what he sees around him in England. It really took off and Americans really liked it. PB: ‘Kinda Kinks’ was very diverse, because you had ‘Nothing in the World Can Stop Me Worrying about the Girl’ – so there was your “lying and cheating” song. You had the cover, ‘Dancing in the Street’ and a duet, ‘Got My Feet on the Ground.’ There was so much to choose from stylistically. There was more writing happening; did that put the band under more pressure? MA: As things developed I think they expected us to do more and more and got two or three hits, anyway, and B sides, and eventually Ray’s songs took over the whole repertoire. It was a natural progression, really, it wasn’t something you could do overnight. It happened gradually. I think everyone expected it. I don’t think anyone thought we should do covers. PB: There was a point in which you were referred to as ‘Pop Culture Sociologists.’ Your song, ‘Plastic Man’ got banned and then there was. ‘Dedicated Follower of Fashion’ which lightly poked fun at the establishment. Things got more intense after that point. Did you enjoy that phase of songwriting and that transition? MA: Yeah. There was a lot of humour in Ray’s songs. Some observations with a bit of tongue-in-cheek humour, as well. But, it’s not obvious. It’s not just rhyming and its poignant words that describe something very descriptive, but it’s got a lot of humour, without being obvious. It’s not digging, it’s just an observation. “There he goes, a chap. A scarlet pimpernel…” It’s like that sort of thing. PB: There was a song called ‘Mr. Reporter’ that hinted at the press relations at that time. Do you feel that the press understood the Kinks? MA: Yeah. I think so. They didn’t take it that hard. It was just a song, just someone’s little light-hearted feel of what reporters were at that time, again, not a real subversion. PB: Is there another trilogy of albums that you think would showcase the Kinks in a comprehensive way? MA: Oh, yeah. We’ve got these first three and we’ve got those others after that. ‘Kinda Kinks.’ We’ve got ‘Arthur’ and all those ones that followed on. ‘Muswell Hillbillies’ (1971) and ‘Everybody’s in Show Biz (1972). There’s quite a few to follow up on. There’s quite a lot of good repertoire, there, because a lot of bands have a couple of hits maybe, and then they’re stuck for material, because no one could write prolifically enough to actually sustain their success. You know, they have to keep playing the ones they made famous. PB: Dave and Ray came from a very large, musical family. They certainly had their share of sibling rivalry. What was your own background? Were you familiar with the kind of upbringing they had? MA: I had a bigger brother, an older brother and I had a younger one. My older brother was seven years older than me, so he was from a different generation. It wasn’t the same thing as being two years apart, not quite the same thing, and we weren’t in the same business, growing up. He was interested in different things, than me, because he was much older. Seven years, when you’re a kid, is a long time. PB: There was documented fighting amongst the members. What made you stay so long given that it was not particularly a smooth journey? MA: You had to understand it, in a way, because you got the general idea of the way they grew up together, et cetera, and it sort of blew hot and cold. When it was hot, it was really good, because they worked together and put their heads together and it was good. But, when it was the other way, it wasn’t too pleasant for anyone, really. It had to be like that, because it couldn’t be hot all the time. It was either mediocre all the time, or really good or really horrible (Laughs). PB: There is so much going on there on ‘Last of the Steam-Powered Trains’, on ‘The Village Green Preservation Society’. Blues-harp, harmonies, rousing dynamics and lead vocals. It was a really full production. How did you approach filling in your part? MA: The thing is it’s a song where you can put yourself in the picture because it’s about the village green or the things that went with it. ‘Steam Powered Trains’ - it’s a train-type song so it’s a train-type rhythm. It’s not quite difficult when Ray plays the general feel. You see where that will fit and that suggests a train. PB: ‘Come Dancing’ was a hit in the 80s and contained a lot of musical twists and turns. It was an amazing tune, but so unlike the previous work. MA: Quite often, when Ray has a thesis of an idea, he would just play through something and you didn’t know what the words were going to be. You just join in and make something of it and gradually you get a feel in it together, and that’s how that one started. He used to record things just to work on them, so he’d have an idea of what it was going to sound like, and he’d change things and come back and run through things again and not proper recording. When you record it properly, with proper sounds, it takes on a slightly different sound and obviously the sound is different and the feel is different, and then when you get the words there’s the structure in your head and you can work out different parts to it. But, again, it’s a development. But when you record it for the first time, it doesn’t sound like it did before, but it’s still good. You get that polished up and in time make it sound like we felt it should in the first place. But it’s got to do with tempo and sounds and working the parts out. I mean, it can’t possibly sound like - when it’s finished, it’s not going to sound like three of you doing it on a cassette tape. But that’s the way it starts off and sort of develops from that, but it’s a starting point. PB: Adding keyboards… how did that alter the composition of the band? MA: Right. That riff that went with it. Da da da, da, da da. He had that drum sound in his head…You can duplicate all these things on keyboard now. Anything you think of, you can get it. But it’s got to be a good sound; it can’t be a drab old sound. It’s got to hit you and you think “It’s good, it’s lively.” It’s just working things out, all the sounds have got to be compatible and all the parts have got to follow on, nicely - the arrangement is quite important. PB: In which phase of the Kinks did you feel you could drum most artistically? MA: Probably the 1970s in a way. I wasn’t mad keen on doing all the big gigs, which happened about 1978 onwards. I left in 1984, so about six years of that. It wasn’t so personal and it wasn’t as much fun, for me, but it was a great sense of encouragement when you do a big gig. But, I think, generally. I enjoyed it more in the 1970s. It was a bit more personal and we knocked around together a bit more. PB: With the Kast off Kinks will you do some recordings with Ray? MA: Yeah. I’m never sure what’s going on. We might want to record, but…it’s not really that important, but…we might get around to doing something. But, I think it would be in the studio, rather than a live recording. Sell it at gigs or whatever. Ray suggested doing something in the studio, but I’m not sure whether it’s going to happen or not. It would be nice to do something. But it has to be something that we’ve done already, but more unusual tracks, because in most of the shows we do it is the most well-known numbers. PB: If a person had not yet heard of the Kinks and you could introduce them to just one song, which would that, be? MA: That would be ‘You Really Got Me’ or ‘Sunny Afternoon’ or something like that. ‘Lola’ (Laughs). It’s spaced-out songs. One is the 60s, one was the first after the 60s. The next biggest hit was about 1966. ‘Waterloo Sunset’ – you’d have to mention that. Another big song that everyone is familiar with…You’d have to go with one that was a world-wide hit. When people ask me, someone who doesn’t know, I tell them, ‘You Really Got Me’ or ‘Sunny Afternoon.’ ‘Sunset’ and ‘Lola.’ That’s just four, but… Probably the ones they would have heard of the most, and then they go, “Oh, yeah.” PB: At which point, in your career, did you say, “Wow. I’m famous. My life has changed?” MA: It was at our first TV appearance on ‘Ready, Steady, Go’, which was just two days after I’d given my job up. (Laughs). PB: Were you nervous about that? MA: No, it wasn’t a very good job. It was only a fill-in job. I delivered paraffin at the time, but it wasn’t a career. It was just a fill-in job. And, when I got sorted out in the music business, we got the TV lined up, because we had ‘Long Tall Sally’ out at the time, and that was fun. And, I thought “This is good (Laughs). They’ve got me on television.” All our relations were watching (Laughs). Yeah, you didn’t know it was going to go on forever. You thought we’d be lucky if it lasted five year. PB: The screaming girls. Was that a new experience? MA: It was quite a change in our lives. We used to do gigs in our spare time and I never had any mass hysteria or anything like that. It was really different. I didn’t take it that seriously really (Laughs). A reflection, I suppose, of young girls. We’re making music and I suppose that’s fairly natural. It was a revolution of music, Beatles, Stones and all that. PB: Do you feel that the Kinks helped propel the punk movement? Did you identify with that genre? MA: I felt the punk wasn’t really musical to me. I think the Kinks were very musical, but I can see from the aggression, point-of-view. But, that was only some songs. It wasn’t every song. You couldn’t compare punk with ‘Waterloo Sunset’, could you? (Mick starts ranting wildly to prove the point). PB: Metallica covered ‘You Really Got Me’ and it sounded like a metronome. Where was the flow that you guys had? MA: It didn’t have the right feel to me. They’ve got the riff starting on the “one,” instead of before the “one.” Three, four, Da Da Da Da DA. Yeah. PB: Has any other band captured that sound? MA: Some of the stuff that Blur did, that was fairly similar and compared. Blur covered it, fairly recently, a couple of years ago, and I thought it was Ray. It was off one of his old albums. I didn’t know the song. But, it wasn’t. It was Blur. PB: Which cover? MA: No, they didn’t do a cover. It just sounded like it. They write their own stuff. PB: They were influenced by the sound. MA: So they were influenced. Started singing like Ray, as well. I said, “Stop it, immediately. It can’t be done. Get your own sound (Laughs)”. PB: I have seen several comments on YouTube videos by fans who felt you have been underrated as a drummer. MA: There’s millions of drummers. Millions of drummers that are better than me and quite a lot that are worse, I suppose (Laughs). No, I think, for the most part, that I was suitable for the Kinks, but, not Mr Wonderful, just sticking with it, and liking it enough to be part of it and making it work. PB: Now that you’ve been involved with a number of other projects, the All Stars, the Kast off Kinks, do you feel a bit liberated from your initial legacy? In other words, how have these other undertakings been different? MA: The Kast off Kinks just started off at a Kinks Club Konvention, for the fans, and so it grew out of that. It used to be held at the Archway Tavern and then it moved on to theBoston Arms. It’s been there for years. Every year it gets better, it’s always for the people. That’s led on to Holland, as well; we go there every year, Utrecht, or every other year. Same thing, but we do it in a pub. It’s good fun. It keeps the songs going and it keeps the people aware. We’ve got Ian Gibbons (Kinks member; 1979-1989, 1993-1996-Ed) on the keyboards and Jim Rodford (Kinks member, 1978-1996-Ed), on bass. We’ve got the guy who has done the Kast Off Kinks from the word, “go,” Dave Clarke, and he’s been with Noel Redding and the Beach Boys, and he’s been around. I had a band with him, a few years ago, called, Shut Up Frank, and with Noel Redding and Dave (Dave Rowberry, keyboardist, died in 2003-Ed), from the Animals. We’ve played together and this idea came up. We just started out at conventions, and, in the last few years, we just do a few gigs as well. We don’t do other things. PB: So, Mick, do you have any additional musical aspirations left? MA: Exhausted myself (Laughs).I’ll just keep doing something until it fizzles out and things seem to..You know, one door closes and another one opens up. I won’t try and go for anything big. I’m quite content, not doing too much, really (laughs). I don’t want to burst a blood vessel at my age. But, I like playing, so I just carry on playing, really. But, I don’t want to play every day. Three a week, that’s plenty for me. But, you know, I play with a couple of other bands that play pubs and functions, and whatever. Just keeps you playing, that’s the main thing. PB: Last question. You’ve done quite a few interviews over the years. Is there one thing that you wished the reporters had asked you, that they never did? MA: Yes. They never asked me if I wanted a drink. PB: (Laughs) Thank you.

Band Links:-

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Kinkshttps://www.facebook.com/TheKinksOfficial

http://www.thekinks.info/

https://twitter.com/TheKinks

https://www.youtube.com/user/TheKinksOfficial

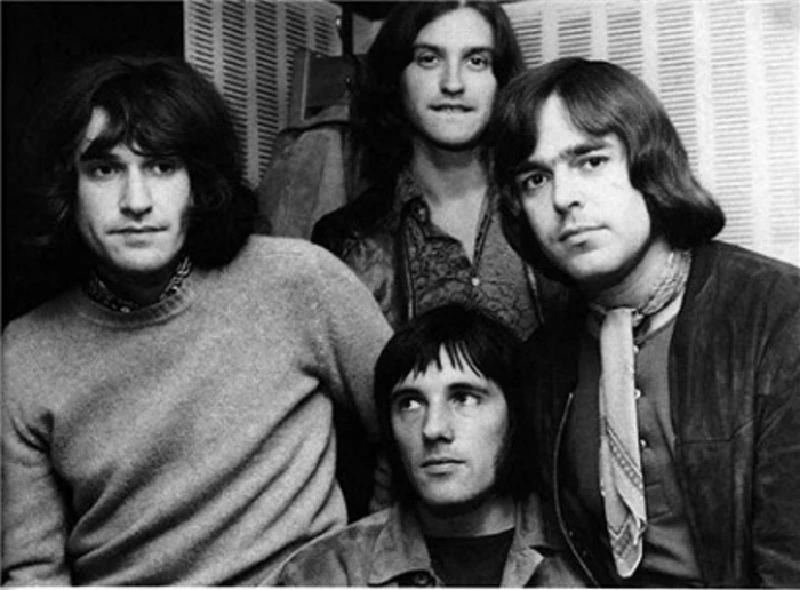

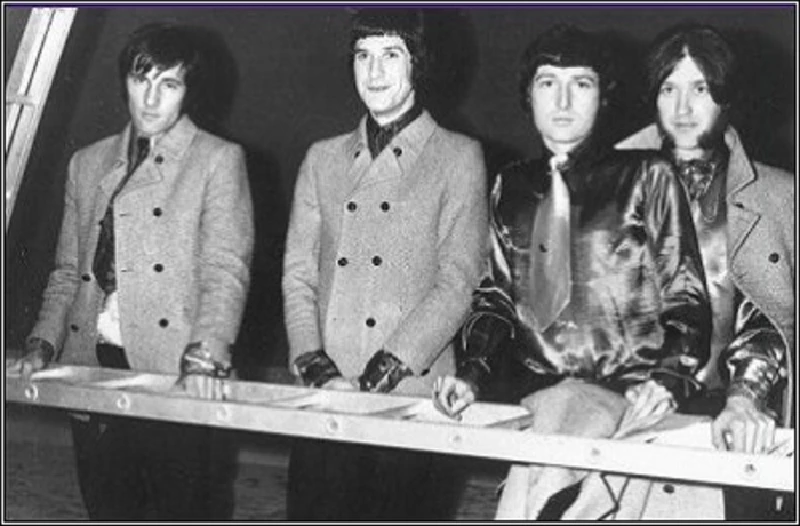

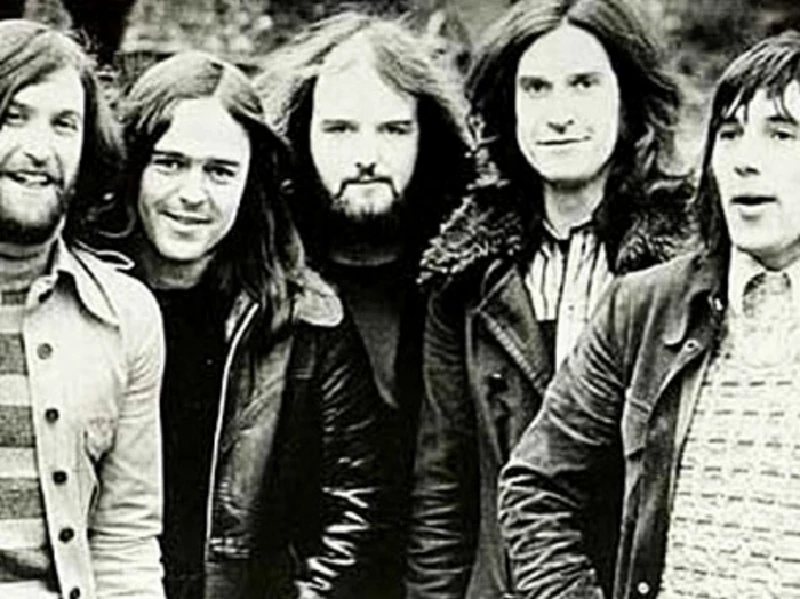

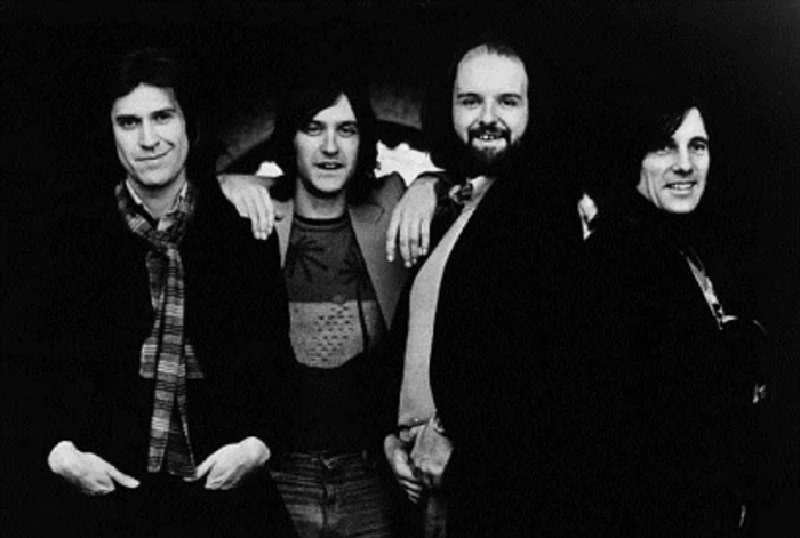

Picture Gallery:-

profiles |

|

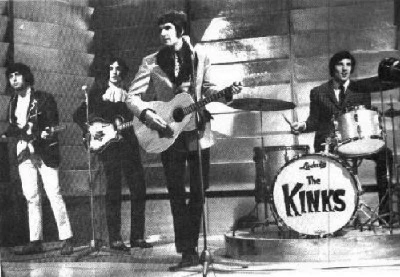

Kinks (2011) |

|

| The Kinks have just re-released their first three albums, 'The Kinks', 'Kinda Kinks' and 'The Kinks Kontroversy', in deluxe editions. Richard Lewis examines each of their three albums and their lasting legacy |

features |

|

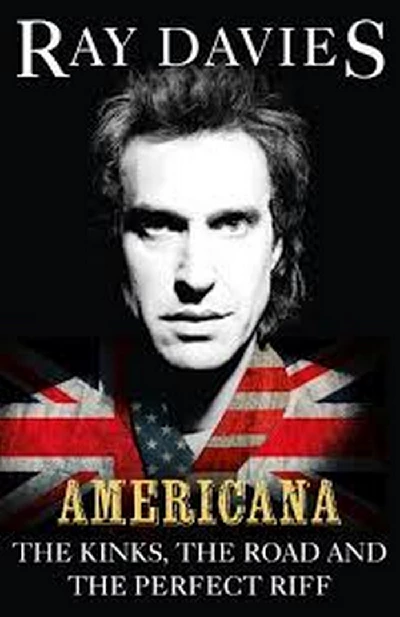

Ray Davies - Americana; The Kinks. the Road and the Perfect Riff (2014) |

|

| In her book column 'Raging Pages' Lisa Torem reflects on the Kinks' Ray Davies' second book of autobiography, 'Americana: The Kinks, the Road and the Perfect Riff', which is about his love and hate relationship with the United States |

reviews |

|

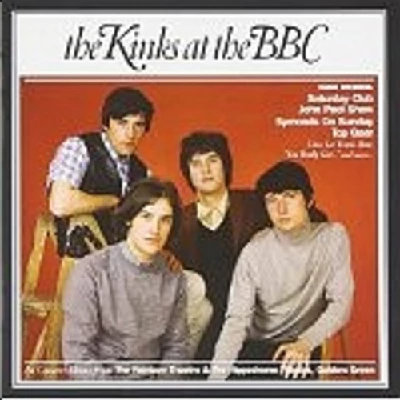

Kinks at the BBC (2012) |

|

| Essential six CD box set of recordings made at the BBC by the Kinks during their thirty year history |

most viewed articles

current edition

John McKay - InterviewRobert Forster - Interview

Cathode Ray - Interview

Spear Of Destiny - Interview

Fiona Hutchings - Interview

When Rivers Meet - Waterfront, Norwich, 29/5/2025

Carl Ewens - David Bowie 1964 to 1982 On Track: Every Album, Every Song

Chris Wade - Interview

Brian Wilson - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

Shrag - Huw Stephens Session 08.12.10 and Marc Riley Session 21.03.12

previous editions

Heavenly - P.U.N.K. Girl EPBoomtown Rats - Ten Songs That Made Me Love....

Allan Clarke - Interview

Manic Street Preachers - (Gig of a Lifetime) Millennium Stadium, Cardiff, December 1999

Oasis - Oasis, Earl's Court, London, 1995

Barrie Barlow - Interview

Dwina Gibb - Interview

Beautiful South - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

Pixies - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

Sound - Interview with Bi Marshall Part 1

most viewed reviews

current edition

Peter Doolan - I Am a Tree Rooted to the Spot and a Snake Moves Around Me,in a CircleVinny Peculiar - Things Too Long Left Unsaid

Garbage - Let All That We Imagine Be The Light

Vultures - Liz Kershaw Session 16.06.88

John McKay - Sixes and #Sevens

Little Simz - Lotus

HAIM - I Quit

Morcheeba - Escape The Chaos

Eddie Chacon - Lay Low

Billy Nomates - Metalhorse

Pennyblackmusic Regular Contributors

Adrian Janes

Amanda J. Window

Andrew Twambley

Anthony Dhanendran

Benjamin Howarth

Cila Warncke

Daniel Cressey

Darren Aston

Dastardly

Dave Goodwin

Denzil Watson

Dominic B. Simpson

Eoghan Lyng

Fiona Hutchings

Harry Sherriff

Helen Tipping

Jamie Rowland

John Clarkson

Julie Cruickshank

Kimberly Bright

Lisa Torem

Maarten Schiethart