Girls Guns and Glory - Interview

by Lisa Torem

published: 28 / 3 / 2010

intro

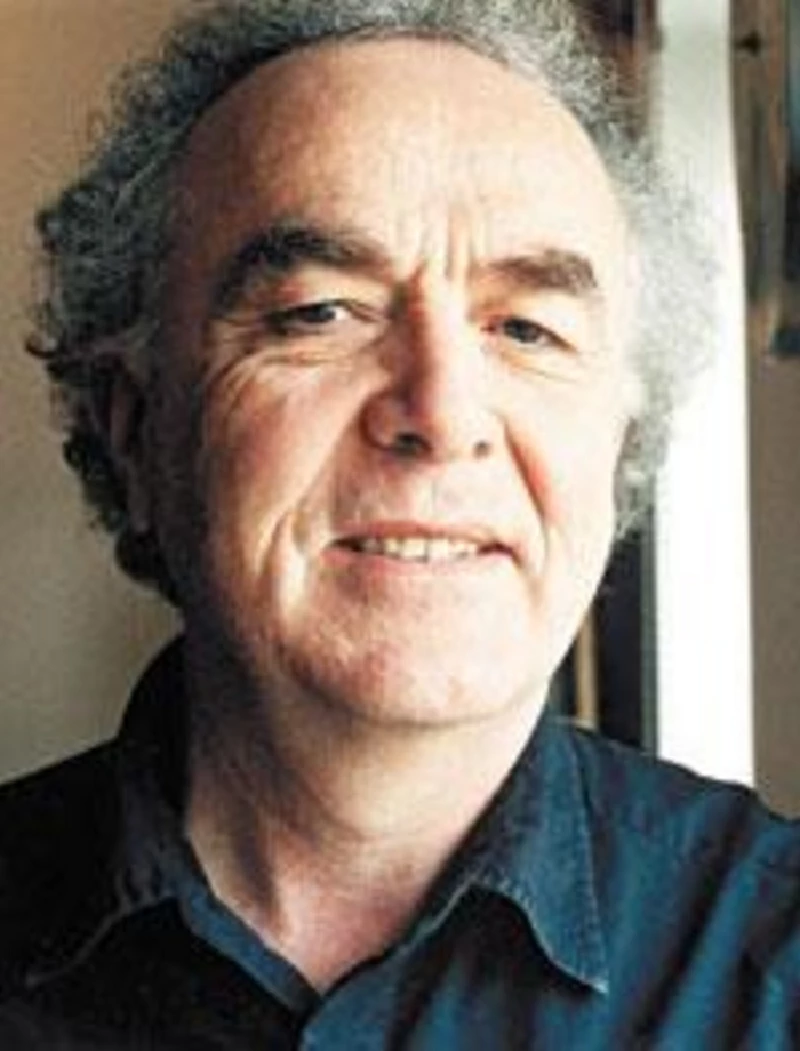

Documentary maker John Edgington talks to Lisa Torem about his films on both Syd Barrett and Robyn Hitchcock

“Look through any window/Yeah, what do you see?”, a memorable line from a catchy pop tune by the Hollies, succinctly sums up the aching curiosity felt after viewing UK director and documentary maker John Edginton’s film screening of ‘I Often Dream of Trains in New York’. The second annual Chicago International Movies and Music Festival, March 5 (Cimmfest.org) sponsored the event and the featured subject of this film, UK’s indie singer -songwriter Robyn Hitchcock, along with Edginton, fielded questions regarding the making of the film, from an enthused crowd. But, though the Q & A resulted in answers to some fundamental questions, a host of back-story details remained unexamined. The kind Mr. Edginton offered me an interview immediately – something rare in today’s society – but I declined, assuming he had already put in a full-day of hobnobbing and networking. But, we spoke early the following week. Then, he cracked open that creaking window and shed rare light on the fascinating mind of the visual artist. Though he has also probed a variety of controversial non-artistic topics, Edginton (Otmooorproductions.com) is not a fledgling in the field of music documentaries. In 2001 he directed ‘The Pink Floyd and Syd Barrett Story’ providing an in-depth look at the psychedelia and genius of the world famous band and founding member, Syd Barrett, whose unfortunate brush with drugs and mental illness, left a permanent and heart-breaking stain on the fabric of this classic, cutting-edge band. Edginton went on to chronicle Hitchcock’s muse in both ‘Trains’ and 2007’s ‘Sex Food Death…and Insects’ (which explored Hitchcock’s whimsical tracks from the album ‘Ole! Tarantula.’) Peter Buck (REM), Scott McCaughey (REM, Minus 5), John Paul Jones (Led Zeppelin) and Nick Lowe, are among the closely- knit group of performers who attempt to define Hitchcock’s unprecedented lyricism. This work, in addition, features Hitchcock’s song: ‘NY Doll’, a tribute to the New York Dolls’ late bassist Arthur Kane, and a riveting rooftop performance. John Edginton’s perseverance shines through during our phone conversation from New York (He shuttles back and forth between the UK and the States frequently). What he captures during each of his films is magical and introspective – he chooses his themes and subjects with great care – but, what’s more intriguing is how, through extensive research and open-minded enthusiasm, he wipes clean the soot and inpenetrable fog that obscures our vision, to serve- up startling clarity to our lives. PB: How long have you been working in film? JE: 25 years. PB: Where are you originally from? JE: I’m from England. I was born in Derbyshire, which is sort of in the middle of England. I’ve lived most of my life around the south of London. I’m basically from Oxford at the moment. PB: What prompted you to first get involved in film? JE: It was a complete accident. I was a journalist. I got involved in film through developing stories which became a television series for Channel 4 in the early 80s. It turned out the television series was going to be a series of documentaries. I didn’t know anything about film at all. I was teamed up with a director and a producer and I learned pretty fast. It was a sort of ordeal by fire. PB: One thing that struck me while looking through your body of work was the documentary ‘Jewish Law.’ I was intrigued by that because, sometimes I think people think Americans speak very freely about religion, but I don’t find that to be true. I’ve actually witnessed people in other countries speaking more candidly and freely about it. Were you hoping that this doc would create a dialogue amongst people of different faiths and that they would discover some kind of universality? JE: Yes. Actually, I made another film about Jewish divorce which is quite a controversial film, but it’s getting accepted into quite a number of film festivals and I expect it will encourage quite a bit of debate. (You can watch it on-line at http://www.channel4.com/programmes/revelations/episode-guide/series-6/episode-1-Ed) I made a number of films about Martin Luther King many years ago. One was about the assassination of Martin Luther King. I had sort of an interest in religion and ethics, and ‘Jewish Law’ came about. If you make documentaries, it’s about how to get yourself funded from one year to the next. One of the ways to get funding through the UK is obviously through television.It’s the primary way of funding. Virtually, everything I do is funded, either partially or fully, by television.The Robyn Hitchcock films were funded by the Sundance Channel in the US. So, I was exploring ideas with the commissioning editor at Channel 4. That series idea came about because of…I always thought it was interesting to look at communities and subjects – they’re not always easily accessible – the kind of world which you don’t normally see. The best kinds of documentaries take you into a world that you have no idea exists. And so, ‘Jewish Law’ was kind of going into the Orthodox Jewish world and opening up and showing that it’s an amazing, rich fascinating world. PB: Let’s talk about the project you did with Pink Floyd and Syd Barrett. Did you have a hypothesis about how you thought the members of the band would feel about discussing Syd Barrett? Were you initially completely open-minded about the outcome or did you change your outlook during the process? JE: Most people originally told me that I would never get information from Pink Floyd about Syd Barrett. The time that I started to do this – which was about ten years ago – the two main protagonists of Pink Floyd – Roger Waters and David Gilmour – weren’t talking to each other and hadn’t been for fifteen years or so. They were at loggerheads and they never did anything together. So, I went into it with considerable intrepidity. But, it was a challenge, you know. This is their kind of legacy in a way. Syd Barrett wrote the first album completely. He was the leader of Pink Floyd, and when he left the band, he became their conscience. They felt guilty about him. They were troubled about what happened to him and he became the subject of their subsequent albums like ‘Wish You Were Here’, ‘The Dark Side of the Moon’ and ‘The Wall.’ They were all about his break-down; the themes of the songs. Anyway, I set about it not knowing what would happen. But, I thought the way to approach it was, honestly, to approach Syd and his family. He was alive at that point and so I met his sister who probably was the only family member who saw him on a regular basis. She went to see him every day. She was sort of a carer in a way. She was very nice, but extremely determined that I shouldn’t make the film. Initially, it took a lot of persuading, a lot of confidence in me. She didn’t trust journalists. They’d also been sniffing around his garbage cans. Paparazzi would take photographs of him and this sort of thing. They didn’t trust journalists, especially didn’t trust me. After a lot of discussion and talk about it, she finally came through to the realization that the film could be a celebration of Syd’s life. PB: Did you feel like it was as well? JE: Absolutely, that was my intention. It wasn’t an attempt to get into an investigation or anything like that. I didn’t want to show him as he is now. I wanted to celebrate his work and his legacy. Just to be an artist’s project – not an investigative film. When she came on board, that immediately triggered the thought of David Gilmour, because I then approached him and he contacted her and she said, “We’re behind this.” So, he said he would do an interview, and, then, it turned out, Roger Waters wanted to do one, too. It may have been that he didn’t want to be left out. But, the result was, in the end, they all took part. PB: At that time, did you know Robyn Hitchcock, fairly well? I know he sang some tributes… JE: No, I didn’t know him at all, actually. Personally, I knew his work. No, that was the first time I met him. You know, Robyn Hitchcock being heavily influenced by Syd? In fact, he said, at one point, that he thought he was Syd. Robyn was wandering around Cambridge. I think he was knocking on Syd’s door, and identified with him very strongly. The thing is, Robyn’s songs – they kind of do similar things that Syd’s songs do. They’re very close to the bone sometimes. They’re sort of emotionally fragile. PB: When you consider a subject for a documentary, John, it’s a huge leap of faith: financially, personally and emotionally, as opposed to a scripted work. So, do you deal with each project with some intrepidity? JE: Well, the element of unpredictability is what makes it exciting. PB: Ah, I see. JE: The old-fashioned school of documentary making was all about getting something planned and almost scripted. They would set up scenes and they would do them over and over again. They would try to make sure they knew what people were going to say before they said it. Do you know what I mean? PB: I believe so. JE: They were scripted and they were almost coaxed into saying what they wanted them to say. It exists still in the BBC. But the thing that excites me about it is when you get into the situation in which you have – you start out at the beginning of the day and you say, this is what people will say and you’re constantly surprised and sometimes it’s a disaster - and sometimes it’s absolutely brilliant. PB: And you like that? JE: Yeah. A little bit. The thing about it now is that it’s not quite as risk-taking. Twenty years ago everything was filmed on 16mm film. People didn’t shoot documentaries on video tapes. So, twenty years ago, you set out with a number of rolls of expensive film – every roll of film lasted ten minutes and it cost at least 100 dollars, more like 200 dollars, just to shoot ten minutes of film, just for the actual film stock. It was a risk – it was unpredictable. But great music documentaries like Dylan’s ‘Don’t Look Back’ and ‘Gimme Shelter’ – they were shot like that. They were filmed by people with little 16mm cameras shooting yards and yards of film (laughs). They had no idea what was going to happen. That’s why they made such great films, I think. But, now, it’s safer, because tape is cheap. Now, it really doesn’t matter, the cost. PB: Would you consider doing an updated film on Pink Floyd’s reaction to Syd Barrett? JE: I’m certainly considering updating that film for a new DVD release at some point. The DVD’s gone through somewhat checkered periods. The original distributors went bankrupt. It’s now been taken over by a company called Eagle Rock. I’ve been talking to them about possibly updating it, including some new material, because it was made before Syd died. So, I think it’s important to bring that up to date. There was a lot of stuff that could have come into the documentary that didn’t. We were restricted into making it into a one-hour slot for the BBC at that time. Now, it can be any length really. I don’t know about interviewing members of Pink Floyd – maybe. Richard Wright is dead too. PB: I know you’ve been drawn to the subject of mental illness; the scandal at Chelmsford, was one example. Do you have any theories regarding genius and mental illness? (Twenty-six patients died at Australia’s Chelmsford Private Hospital during the 1960s and 1970s ‘Deep Sleep Therapy’ refers to subjecting mental patients to long periods of barbiturate –induced comas) JE: I’m interested in mental illness partly because of experience in my family. I’m kind of interested in it as a subject; the causes and what the treatments are. ‘Deep Sleep’ was about the arrogance of a psychiatrist who caused the deaths of a lot of people through an untried therapy. I made a film ‘Hearing Voices’ which was about the experience of people who hear voices. The ‘Syd’ story? I actually started thinking about doing a film about LSD and mental illness. PB: That would be fascinating. JE: I thought about it. I thought, maybe do it and tell it through the experience of someone like Syd Barrett, and that way, try to bring out the issues and the tragedy of it. PB: So do you think that’s what happened to Syd, the LSD? JE: I think so, yeah. There’s a story in the film that he changed completely over one weekend. I am not sure if it all happened in one weekend, but he was expected for a BBC radio recording and he didn’t turn up. At the end of the weekend, he was in a catatonic state. He was living in a house full of people taking LSD and he took it all the time, without really recognizing there could be consequences. PB: I know you worked with Robyn on two documentaries; he played with the Venus 3 and with Terry and Tim. Did you forsee a different dynamic for each of those films? JE: The first one – talking about taking a risk and plunging in – I’d been talking to the Sundance Channel and BBC about making the music documentary and they kept saying, “Maybe maybe.” I had various ideas and various names. Nothing was coming off and I had lunch with Robyn one day, in London. He told me that in about a week’s time, his house was going to be full of musicians, for a week or so; he was going to have a recording unit set up in the kitchen. They were going to make a record in his house and it’s a very small cottage-y west London house. And I thought, this could be fascinating. And, then he told me who was going to come: half of REM, John Paul Jones was going to drop in and that sort of thing and I said, “I think I’m just going to have to film this” and he said, “Yeah, I think you probably are,” not knowing what this would lead to. So, I filmed it for five days and it did trigger the Sundance Channel and BBC kind of saying: “Ooh, yeah. This is great, you know?” Sundance Channel funded it in the end and what I wanted to do was then go on tour with them, which we did, in the States, about a month later. That was really when the money had to start flowing. But, they backed it. That was very fortunate. BBC4 then came in as well. (The full documentary with extras, ‘Robyn Hitchcock :Sex Food Death…and Insects’, is now on DVD). My intention was to get into Robyn’s world, the process of songwriting. He was just making up songs on a daily basis, sort of developing them with a band as he went along. He said, “I don’t even know what some of this stuff is. I just started singing it” – very much off the cuff. Some extraordinary music developed from that. It’s all on his new record ‘Propeller Time.’ All those tracks were tracks from that first film: ‘Sex, Food Death…and Insects,’ and the second one, ‘I Often Dream of Trains.’ PB: Where was ‘Trains’ filmed? JE: Robyn had been on a tour of the States and he was on the train from Boston to New York. He had been in Boston the night before. PB: I liked how you approached those scenes on the train. They flowed so well. JE: Thank you. PB: Who will be most affected by ‘Trains?’ The die-hard fans; the fanatics that I see everywhere he plays? JE: I would like to attract people who don’t know who he is. This is interesting. The film was shown in a festival in London: ‘The Raindance Festival’ in October, in a West End Cinema. It was sold out. Then, they had the second screening and what was interesting about it was, a number of people came who didn’t know who he was, but they had passes for the festival. So, they were discovering Robyn for the first time and people seemed to really, really enjoy it. “Oh, my goodness me, this guy’s been around for 30 years and I’ve never heard about him.” He’s one of those people who has been a cult figure that nobody’s heard of in the UK. He’s a bigger name here in the US than in the UK. PB: Interesting, isn’t it? Do you notice any cultural differences between how British and American audiences react to Robyn’s humour? JE: Americans might react more to the Englishness and a kind of whimsy, whereas the British are more used to that maybe. In terms of his stage shows, you either love it or hate it. (Laughs). Some people just can’t take it at all. PB: Why? JE: Ramblings. PB: They can’t take the ramblings? JE: You have to have a sort of kind of sense of humour yourself in the audience, don’t you? To get it? Otherwise, you just think this guy’s rambling off his head. Some nights people are absolutely hysterical. Other nights, they’re just sitting there not laughing, and you say, what is it? Some sort of atmosphere in the audience? They either get it or they don’t. I don’t know. PB: Even in the States you would get those differences – maybe club to club. JE: I think it’s the songs.I’m always amazed that there are so many young people. You can go to a concert and see Robyn in Brooklyn and half the people are under 30. They know his songs. They know them. PB: Are you both mavericks in the way that you’re not going for the most commercially viable product? You go for the real depth of what you’re looking for? JE: Robyn and I don’t set out to make money, though, we hope we do on this one. I think we both kind of – our work is really to get satisfaction from creating something good. We enjoy the responses when it gives something to the audience, and as for the commercial side? The funny thing I found in filmmaking is that the films that you least expect to make any money at all are the ones that sometimes do. If you set out to make money, it never works. PB: Who are your favourite filmmakers? JE: Well, I love documentaries, obviously. Those films I mentioned and the D.A .Pennebaker films of the 60s like ‘Don’t Look Back,’ the Maysles Brothers – those great American documentary makers that kind of pioneered that kind of “fly on the wall” – not just someone sitting someone in front of the camera, but traveling into their world. The whole thing about ‘Don’t Look Back’ is that it’s really probably the first film documentray that ever attempted to get behind the scenes and inside the head of somebody, into traveling around on tour and the performances are almost secondary. It’s what goes on in hotel rooms that’s much more interesting, that kind of approach in a way. I tried to adopt that approach with Robyn. PB: How did you make choices about the shots in terms of who is telling the story, or do you determine that during the editing? JE: You carry it in your head; the sense of what the look and feel of a film is. You have to start out with the style of the approach. What I tend to do is combine observing what’s going on without intervening and mixing that with attempting to go deeper by interviewing. So, Robyn will be creating and making songs and I will spend hours filming what’s going on between the groups of people, and then at a later time, I’ll sit down and look at all that material and think about it. Well, what is it behind all this? What’s motivating him? One of the things I’m interested in is; what was the thought behind his humour? What makes him, shall we say, whimsical? And I began to think that it’s maybe a kind of defense against revealing too much of his inner world, because there’s a lot of darkness in his songs, as well. I decided that I wanted to get to the heart of that and bring it out. At one point, I sat him down and had an interview about it. At that time, we hadn’t been that close, but he is somebody who – he kind of jokes about things - but it’s a very dark place. PB: Last question. Do you think you’ll film Robyn again? JE: I should never say never, should I? I would probably say, probably not, because one has to move on, and we made two films about him. There are a lot of other people in the world, a lot of wonderful subjects. He’s such an irrepressible person, and I continue to see him. He’s a friend, you know (Laughs). Who knows? PB: Thank you, John. Special thanks to Pennyblackmusic writer Jon Rogers for help and information on Syd Barrett.

Band Links:-

https://www.facebook.com/girlsgunsandgloryhttp://girlsgunsandglory.com/

https://twitter.com/girlsgunsglory

Picture Gallery:-

soundcloud

reviews |

|

Good Luck (2014) |

|

| Accessible and socially conscious country rock on fifth album from Bostonian-based band, Girls, Guns and Glory |

| Sweet Nothings (2011) |

most viewed articles

current edition

Carl Ewens - David Bowie 1964 to 1982 On Track: Every Album, Every SongArmory Show - Interview with Richard Jobson

Bathers - Photoscapes 1

Colin Blunstone - Thalia Hall, Chicago, 16/7/2025

Visor Fest - Valencia, Spain, 26/9/2025...27/9/2025

Billie Eilish - O2 Arena, London, 10/7/2025

John McKay - Interview

Robert Forster - Interview

Loft - Interview

Sir Tim Rice - Interview

previous editions

Heavenly - P.U.N.K. Girl EPManic Street Preachers - (Gig of a Lifetime) Millennium Stadium, Cardiff, December 1999

Oasis - Oasis, Earl's Court, London, 1995

Trudie Myerscough-Harris - Interview

Beautiful South - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

Pixies - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

Prolapse - Interview

Simon Heavisides - Destiny Stopped Screaming: The Life and Times of Adrian Borland

Paul Clerehugh - Interview

Doris Brendel - Interview

most viewed reviews

current edition

Amy Macdonald - Is This What You've Been Waiting For?Sick Man of Europe - The Sick Man of Europe

Alice Cooper - The Revenge of Alice Cooper

Phew, Erika Kobayashi,, Dieter Moebius - Radium Girls

Davey Woodward - Mumbo in the Jumbo

Lucy Spraggan - Other Sides of the Moon

Blueboy - 2

Cynthia Erivo - I Forgive You

Vinny Peculiar - Things Too Long Left Unsaid

Philip Jeays - Victoria

Pennyblackmusic Regular Contributors

Adrian Janes

Amanda J. Window

Andrew Twambley

Anthony Dhanendran

Benjamin Howarth

Cila Warncke

Daniel Cressey

Darren Aston

Dastardly

Dave Goodwin

Denzil Watson

Dominic B. Simpson

Eoghan Lyng

Fiona Hutchings

Harry Sherriff

Helen Tipping

Jamie Rowland

John Clarkson

Julie Cruickshank

Kimberly Bright

Lisa Torem

Maarten Schiethart