Bad Examples - Interview

by Lisa Torem

published: 15 / 1 / 2012

intro

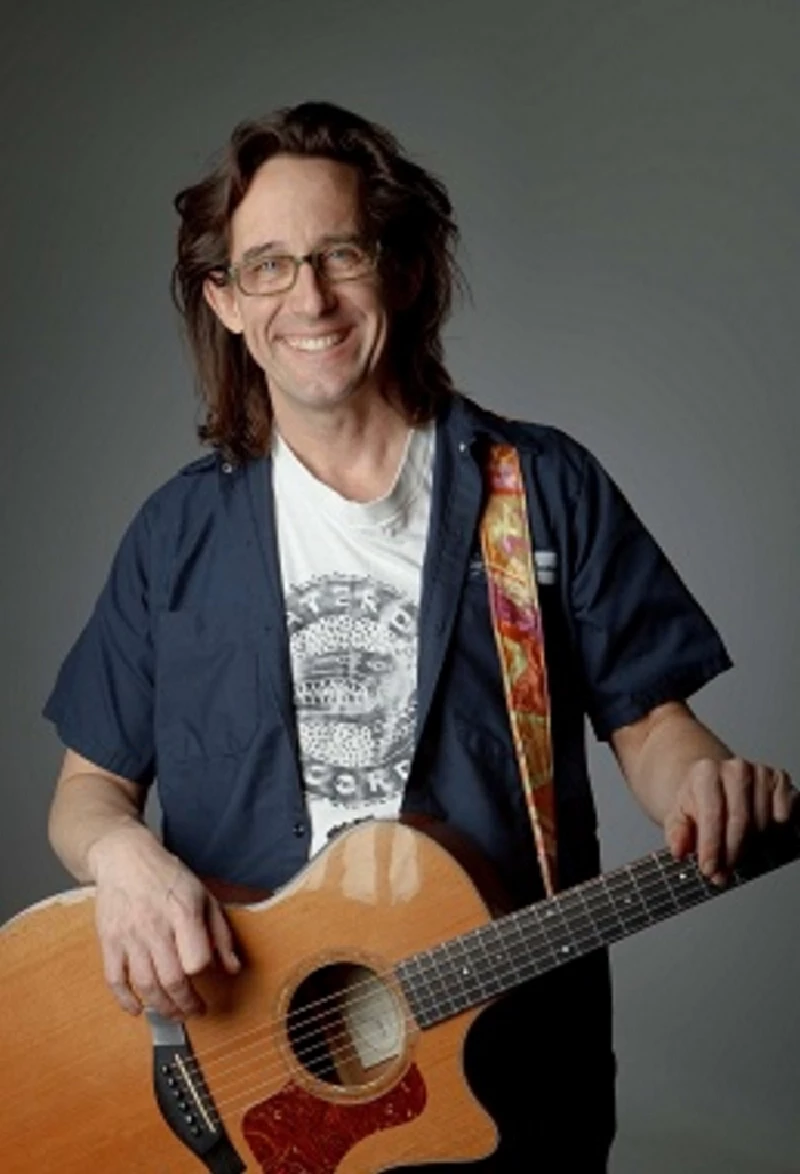

Lisa Torem speaks to Chicago-based musician and singer-songwriter Ralph Covert about his band, the Bad Examples, and long solo career

I first met singer-songwriter and guitarist Ralph Covert while he was teaching a children’s music class. I expected to hear traditional, predictable songs like ‘Lightly Row’, so when he performed the energizing rhythms and intelligent lyrics that made up his originals I was stunned. “Who is this guy?” I thought. His pop-rock group, the Bad Examples, which formed in 1987, has enjoyed a huge following in Ralph’s Chicago, but has also garnered an impressive national audience. In addition, they have also attracted major attention in Europe, especially Holland. Ralph’s diverse musical interests are reflected in his compositions. And, though he can certainly play “garage rock”, his material is more often characterized by complex modulations, lavish harmonies, dynamic vocal hooks and introspective character studies. When I took his songwriting class, the best part, besides pooling our money for a quick beer run, was watching him crank up a guitar riff as he waltzed us through the inner workings of an arrangement. Ralph agrees that, “That was a special time.” And since then his career has taken off in a million directions. With his family-centered rock group Ralph’s World, he received a Grammy nomination for Best Musical Album for Children (‘The Sixth Green Gorilla Monster and Me’). Musical theatre co-writes with G. Riley Mills, ‘Sawdust and Spangles’ and ‘Streeterville’ have received Jeff Awards for Best New Work. The American series, ‘Six Feet Under’ (HBO), used the Bad Examples’ ‘Not Dead Yet’ in an episode. Their recent ‘Smash Record’ recording features the best studio work of the Bad Examples since 1995. But, for me, the best part was that, on my birthday, Ralph agreed to come over for an in-depth interview, where we got to discuss his age-resistant passion - songwriting. PB: What are your musical influences? RC: I fell in love with the Beatles, was seduced by the Rolling Stones and then had affairs with David Bowie, the Who and Elvis Costello. Over the last ten to twenty years, other artists that I love have included the Penguin Café Orchestra and Elliott Smith, who said he was always trying to unravel cool puzzles. There’s Serge Gainsbourg and more recently Josh Ritter, Goldspot, and a lot of world music. PB: Can you give us a brief history of the Bad Examples? RC: Sure. We first put together the band in the late 1980s. It will be 25 years in March. We had initially Terry Wathen on drums and Greg Balk, the bass player. We were just a trio. I immediately wanted to book a show, so I called The Hidden Cove –- at the time they didn’t have live bands. I told the guys we had a gig and they said, “Awesome.” They asked if someone else was playing there. “No, it’s just us. Three sets.” They said, “But we only have seven, original songs…” (Laughs) I said that I think we can fake our way through. We played every lame cover we knew, and repeated those originals at least three times. But as a young songwriter, I felt that I wanted to get [my songs] in front of people. We really needed a demo. I had about 75 odd length cassettes – I thought we would use some of those songs plus another three that I had hanging around, which fitted perfectly onto this 14-17 minute cassette. We had a photo of the band naked in front of our instruments. I certainly couldn’t use it for promo, but it cracked me up. We called the album ‘Meat’. Then, about two months later, we played at The Hidden Cove again, and I had this other idea. On every cassette, I taped a condom. At the beginning of the show in this skanky dive bar, we’d sell these cassettes with a condom taped to the front. By the end of the show we were selling condoms with a tape attached for $5. There was no such thing as a condom machine there (Laughs) and we ended up selling all our albums out pretty much immediately. We went through a couple of line-up changes. Our guitar player and the original bass player left. I tried to get Tommy O’Brien to join the band originally; then I bumped into him, almost a year to the day of when I first put the band together. He said, “Ralph, you know what? I was hoping I’d see you around. The biggest regret I ever had in my musical career was saying ‘No’ to you. I think about it all the time. I thought, ‘I should have joined that guy’s band.’ I didn’t do it because I hated your bass player, but I should have made the best of it.” So I said, “Last week my bass player and my guitar player quit. Excellent. Now, all we need is a bass player.” Tommy says, “Excellent. Pickles Piekarski just broke up with the Rockamatics.” We kept asking Pickles, but he thought that we were a ‘pop band’. We spent seven months auditioning bass players. The scenes didn’t mix back then. The purist musician really didn’t take off. My songs are really chordy. Now by the time it got back through the grapevine, Pickles had heard that we were saying, “Nah, Pickles wouldn’t be any good for us. There are too many chords and he can’t play them.” Then he called to audition for us. He’s just a sublime bass player. It was so amazing, but, just as a formality, we asked, “Do you want to join our band?” He said, “No” (Laughs). He wanted to do it just to show us that he could do it. PB: So how did you finally get Pickles onboard? RC: At Fitzgeralds, he told the owner, Bill, the story, and Bill answered, “Pop music, blues music? I think Ralph Covert is one of the best songwriters in the city. Man, I love your playing. To hear you play with him, I’m so sorry. I would have loved to have seen that happen.” About a week later, Pickles called. “Just checking. Do you have a new bass player yet?” (Laughs) And we’re off. We started to work with Michael Freeman, a legendary producer of indie bands. We were playing shows and really growing as a band. I wanted to learn the roadmap of making an album with ‘Bad is Beautiful’. I wanted to figure out how to start with the songs and end up with a record. All the money we made from the gigs, we put right back into the studio. Dennis De Young heard ‘Not Dead Yet’. This is Dennis De Young, from Styx (Laughs). He fell in love with it and wanted my permission to record it. Styx had never really done an “outside” song. I went to his house, and found out later he had considered asking me to join the band. PB: Would you have done that? RC: No. I had my own band and I wanted to make my own music We put ‘Not Dead Yet’ on ‘Bad is Beautiful’ because I didn’t want a song of mine, already on ‘Meat’, to be thought of as a Styx song. This was going to be our big album – we’d better put this song on it. (Styx covered ‘Not Dead Yet’ on their 1990 release, ‘Edge of the Century’-LT) At that time, Columbia College started AEMMP Records, their student label. Each year, out of hundreds of submissions received, they narrowed the list down to two or three finalists and then released a single. By the time they held their showcase, where the runners-up and headliner would perform, they had already made their final decision about which song would be released. The Bad Examples, one of the runners-up, opened for one of the finalists, that the whole class had come to watch. But the AEMMP people were so impressed by the Bad Examples that they released the 12-inch, ‘Not Dead Yet,’ instead of their original choice. Then as a result of that I got a call from a Dutch record executive, Fred Haayen (The Who, Rod Stewart-LT). I knew from my research how much money to expect from a European record deal. He asked how much he would need to invest in the band. I’m thinking $30,000. He says, “We can do that. Let’s get the contract and negotiate it.” I listed all the things that I wanted to include in the deal; publishing, keeping my American rights, etc. Tommy meanwhile had given me a Telex machine. It was a rudimentary digital typewriter. So I retyped the 35-page contract by hand. It had a dot matrix printer – it was the most amateur thing on the planet. I put it on the desk. “This is the deal I’m offering,” I said. He said, “Could I have my secretary type it at least?” (Laughs) We basically got that deal and that’s how we got our record out. I wanted to release the record on our own in America. I had the money to finish it. We had met Jay Whitehouse, the former national sales manager for Alligator Records, who had played in the Indigos. He had said, if he ever had his own label, the first thing he would do would be to sign The Bad Examples. Later on, I asked Jay, “Do you remember when you said that if we had proper funding, you would release our album?” I told him that I wanted to start a label, which, funded by Jay, became our regular label, Waterdog. In 1989 we quit our regular jobs and I bought a motor home. That was when all the record deals fell through. The ‘Take It on The Chin Tour’ was all of 1990. Tommy O’Brien had quit the band. He had bought a house. (He was replaced by blues guitarist, John Duich-LT) We toured both here and in Europe. We played three sets a night, five nights a week. John described the process as, “Drive, load in, play, load out, drive, load in, play, load out, drive…” PB: Weren’t you exhausted? RC: We were really exhausted, but we were focused and we wanted success so bad. Around this time, Nirvana had started the “Alternative” genre. A label called and asked if the Bad Examples could sing off key and play sloppily. Jay said, “Fuck off.” ‘Cheap Beer Night’ was scheduled to come out, but its European label, CNR, went through this major collapse. The new CEO had embezzled millions of dollars, so the company was, all of a sudden, gone. The deal had just vanished. Do we continue our tour and then tour for another year? But at a certain point, there was the physical toll. PB: And the emotional toll? RC: Yeah. John left the band to explore his blues roots. Steve Gerlach joined and totally revitalized the band. We weren’t touring as much nationally. We stayed local. We got into this heavy duty rehearsal schedule. I was writing so many songs and we were rehearsing two or three times a week, over at the Beat Kitchen, a great club. We recorded, and it was such a great, raw sound. Pickles, Terry and Steve were so tight at the time: They had such clarity about what they wanted. We recorded ‘Kiss 50 Cents’. Everybody knew exactly what they wanted. There might have been one or two records that were second takes. Terry would go in, do a shaker part. I’d go in once, do a vocal part, come back…First take, boom. First take, boom. First take, boom. But we were dead broke and dead exhausted. Critically there was a huge buzz about the band, but we didn’t have the resources. We put the record out on Waterdog, but we didn’t have enough money to do anything with it. Terry wasn’t having any fun, and Steve really wanted to do his own thing. I’d been meeting with managers and lawyers, shopping the band, and Terry and Steve just said, “Can’t do this.” Terry left the band. Steve, being the team player that he is, knew he wanted to leave the band, too. When he first joined, there was this solo thing he wanted to do. But he said, “I’ve always loved you guys. I knew that if I didn’t play guitar with the band, I could see what was going to happen with you.” The chemistry was so great. Steve had always thought of this as a temporary thing, but when Terry left, he said, “I can’t leave.” PB: He must have felt a great deal of loyalty. RC: That’s when drummer, John Richardson, joined the band. After about a year, Steve moved on. In the mid 1990s, there was Pickles, Tommy O’Brien, who rejoined the band and me. We were still playing every weekend, but there was just enough money to pay the rent and it just wasn’t enough. PB: How badly were you struggling? RC: There was no moving forward – we were treading water. We agreed that we’re not breaking up, but if you do this every weekend for the next five years…At that point, we still loved each other and we still loved making music. John Duich passed away from a heart attack – so John was gone. We did a three-set show, ‘The 5000 Days Show’. We played songs that spanned the history of the Bad Examples. The CD would be released on the band’s 5000th day anniversary. I had this really, really, vivid dream of John Duich before the show. He was sitting on the couch, just looking at me as if he was pissed off. I’m like, “What?” He says, “You’ve got a lot of nerve, Covert. You’re doing your 5000 Days Show, all the line-ups, all the guitar players, and I’m not invited?” I say, “John, you’re dead.” He says, “Fuck it. I thought you’d be smart enough to figure something out.” He gets up and leaves the room (Laughs). I get up from the dream, and it’s as if he’s sitting next to me. I think, okay, I’ll take studio recordings, one of the songs that John would sing, from the ‘Cheap Beer Night’ sessions and we’ll strip out his guitar and vocal. So in the middle of each set, we sang one original blues song. One of the guys even blew up a life-sized picture of John. Tommy O’Brien and Steve Gerlach played together for the first time. They’d both played in the band for ten years, but never together. They realized that they not only knew all of the songs completely, but that their approaches to the guitar parts were so perpendicularly different. They found themselves onstage, orchestrating and playing harmonies together. Most guitarists don’t want another lead around. But they’re both saying, “I’ll do it if he comes…” Then Ralph’s World started taking off. ‘Smash Record’ came out of that whole decade: making music that we just loved, in the studio, with no label, no pressure, and no need to release it. Those songs were languishing on unfinished tapes and I had them translated to ProTools. We added guitar here, a little guitar bit there, and we fixed it up. Suddenly, it’s like a slot machine going tick, tick, tick. ‘Smash’ fell into place. That album was about making songs that we loved. PB: Reviewing your work is like examining Picasso’s life. Your songs reflect many temperaments. ‘Big E Chord’ is, for example, great rock, but my favourite ballad is ‘Adam McCarthy’. Tell me about that track (‘Adam McCarthy’ appeared on a 1995 solo EP of the same name-LT). It has a complex chord structure. RC: Steve Gerlach just listened to the song and played along with me. PB: How do you write a song like that? RC: The most important thing is focusing on listening to your songwriter compass. That voice inside that says, “I like that. I don’t.” Writing a song is about making choices and trying to be pure and honest within that process. I break songwriting down into rhythm, lyrics, music and the emotional centre. Music includes both melody and harmony and rhythm includes the beats, but also the structure of the whole song. I had a period in the 90s where, over the course of about nine months, just by pure fluke, either a close friend or someone I knew pretty well, died. One a month for nine months. Some were musician friends; some were just people I knew. The circumstances were just bizarre. I’d go to the neighbourhood bar to have a drink and I’d see a guy that I knew from five years before. My first wife and I used to go over to his house and have a beer. I hadn’t seen him ever since. “Bob, I haven’t seen you for years. How are you, man?” He said, “Jody got shot by a gun last night…” Another musician, a dear friend, played a gig, drove to his parent’s house, parked the car in their garage, and found an intruder. What the fuck! There was stuff like that; that was so senseless. Bruce Howe did the ‘Cheap Beer Night’ album cover and graphics. I saw him when he was finishing off the record and then went back on the road. He finished the record and had his big annual party. He was feeling kind of tired, so he went to see his doctor and found this big, grapefruit-sized tumour. He was dead, a month later -- things like that. You’re young and there’s nine in a row. I’ve always been a fatalistic person, but… Fast forward, I took an improv class and we were asked to do monologues on the spot. Everyone was trying to be funny, but no one was. I said, “Screw being funny.” So I get up in front of the class and I say, “I’ve got Aids.” I just explored my emotions. I said, “I know it’s this thing that I’m supposed to be. I know I was an idiot. I should have used condoms. Fuck me, right?” I went through the emotions. I was just angry. I went there as if this was really happening. The teacher looked at me, and said, “I think we should take a smoke break.” We went outside. I said it was an improvised monologue. They said, “Oh, my God!” Then I went home. It was this really powerful thing because I had so let myself go to that place, and that experience I had writing ‘Adam McCarthy’ was like the experience I had of visiting Bruce, right before he died. I’d been calling and calling him once I got back off tour and I didn’t know what was going on. I finally got his girlfriend. “Come over, yeah.” I walked in and he’s sitting there in the hospital bed. He’s showing me pictures of his big monkey ball bash, and he was smoking. He said, “It’s not going to kill me,” but he died shortly afterwards, But that was all within a period of nine months and it was too much. It was all locked in that emotional box. But after that monologue I was able to sit on the other side. I actually wrote that song in fifteen minutes. It just came out, but I didn’t play it for anybody. Then I was driving back from Colorado. In the original last verse of the song, I sang, “I said, I’d come back when I could, but he died in the end.” Something was funny in that song. I suddenly realized on the trip back from Colorado it was a lie. I was too chicken to go back and face Bruce a second time, so I didn’t make it. As I was driving down the road, I changed the lyric to, “I said I’d come back when I could, but I never did make it.” PB: You describe the sorrow of those left behind. RC: I guess the thing that resonates with me is that it’s kind of – selfish. The “me” singing the song is grieving -- PB: But you are the one who is left – RC: Yes, you are left. That’s not fair. But ultimately, what about ‘Adam McCarthy?’ What about this person that’s not going to have this? What about all the crap that he’s going to miss? You’re never going to be lucky enough to have a hangover. PB: In ‘Your Ex-Girlfriend’ - WHAM - you let the new guy have it with the lines “I’m still livin’ with your ex-girlfriend/We’re as happy as we could be/I get so kinky with your ex-girlfriend/You wouldn’t believe the good things she does to me.” RC: In Amsterdam, I was working with the Moondogs. I fell in love with their music. I approached them on tour supporting the ‘Birthday’ album. I said I’d love to have the Bad Examples perform with the band. I went out for a beer with their main guitarist/singer/songwriter and we hit it off. I ended up recording and touring with them. (Ralph co-wrote ‘Rikki Doesn’t Worry’ with Moondog, Rik Vrijman, which won a Dutch music award for best lyrics-LT) Later on we did a concert and I had an hour’s walk home. The line, “I’m still living with your ex-girlfriend” came into my head and it was so snarky. PB: It’s deliciously bitchy! RC: I know -- it’s so bitchy and it just popped into my head at about 4 a.m., as I was walking home in Amsterdam, just singing to myself. I thought, “I wonder if I can top that.” I was having so much fun wondering how I could outsmart that last line –- how I could make it even nastier. How could I go further? PB: You got together with the English singer-songwriter Jason Feddy. RC: Jason was a big fan of my music. ‘From Ragtime to Rags’ was part of his live set. His management found out I was in Europe and invited me over to write with him. He made a call to check in with his girlfriend from Harrogate, a beautiful city in the wealthy part of northern England. It has sixteen all-girls finishing schools. These rich girls go there and they know they’re going to go home, back to mom and dad and get married off to some, rich snooty dude, so this is their four years to party. So Jason says, “I’m going to call the Blues Bar to see if my baby’s there.” He just meant that if she were there, he’d get her. But I’m from Chicago. So when I hear a line like, “I’m going to call the blues bar (Blues Bar Harrogate) to see if my baby’s there”, I have the song half written before he comes back in the room. We wrote, ‘Harrogate Blues.’ Then, years later, I actually had this opportunity again. Jason’s manager set up a bunch of tours in England. So the two of us got back together at the Blues Bar. We started at noon and played until about 6:30. A video circulating on YouTube showed that the crowd bodysurfed me across the room, up the stairs of the balcony, and then over the balcony down to the crowd and back to the stage. PB: What motivates two self-contained writers to work together? RC: They’re bringing different choices. The fun is you’re following both of your songwriter compasses. They bring different ideas then you would. It pushes you out of your comfort zone into something a little bit different. PB: What compelled you to write children’s music? RC: I’d been teaching songwriting at The Old Town School in Chcago. Jackie Russell, of the childrens’ program, asked me to teach a Wiggle Worms class. She said, bring your daughter and do whatever you want. Meet the other parents and kids and just be yourself. I really enjoyed playing for them. Tim Powell had a son in the class, and asked me if I wanted to do a kids’ record. I said, it would have to be a great record with great songwriting and great production. He said, “You just cracked the code.” My philosophy is there’s no such thing as a good album. There are only great albums and forgettable albums. Every good album is a forgettable album. I took the same approach here. We approached it like we did an indie record. We played in rock clubs in the afternoon; we started touring and working the press. Nobody was doing that. It took off and contributed to this “kindie” music genre. PB: Were you surprised at the outcome? RC: Yes, I had no idea how much I would love it. Now, we are creating a self-funded Ralph’s World TV show. We’re shooting in Charlottesville. Like with the Bad Examples, we just rolled up our shirtsleeves. We paid for it. We did it. I’m also doing a monthly show called Ralph Covert’s Acoustic Army. People bring their guitars and I do all of my original stuff. I encourage the audience to play along. PB: Thank you.

Picture Gallery:-

Visitor Comments:- |

| 533 Posted By: lisa, chicago, il. on 15 Feb 2012 |

|

Ralph has managed to please both the kids and the adults with his music, and even created an album of Bad Examples tunes especially for the younger set.

I think he has a rare gift.

Lisa

|

| 522 Posted By: Terri & Rob Williams, Harvard, Illinois on 03 Feb 2012 |

|

I've seen both the Bad Examples and Ralph's World. Ralph is extremely talented, and as far as I can tell, he loves and enjoys LIVING LIFE! (Terri)

|

most viewed articles

current edition

Carl Ewens - David Bowie 1964 to 1982 On Track: Every Album, Every SongArmory Show - Interview with Richard Jobson

Colin Blunstone - Thalia Hall, Chicago, 16/7/2025

Bathers - Photoscapes 1

Visor Fest - Valencia, Spain, 26/9/2025...27/9/2025

John McKay - Interview

Editorial - July 2025

Billie Eilish - O2 Arena, London, 10/7/2025

Sir Tim Rice - Interview

Bathers - Photoscapes 2

previous editions

Heavenly - P.U.N.K. Girl EPManic Street Preachers - (Gig of a Lifetime) Millennium Stadium, Cardiff, December 1999

Oasis - Oasis, Earl's Court, London, 1995

Beautiful South - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

Trudie Myerscough-Harris - Interview

Pixies - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

Simon Heavisides - Destiny Stopped Screaming: The Life and Times of Adrian Borland

Paul Clerehugh - Interview

Doris Brendel - Interview

Prolapse - Interview

most viewed reviews

current edition

Amy Macdonald - Is This What You've Been Waiting For?Sick Man of Europe - The Sick Man of Europe

Phew, Erika Kobayashi,, Dieter Moebius - Radium Girls

Alice Cooper - The Revenge of Alice Cooper

Davey Woodward - Mumbo in the Jumbo

Lucy Spraggan - Other Sides of the Moon

Blueboy - 2

Cynthia Erivo - I Forgive You

Lapsley - I'm a Hurricane, I'm a Woman In Love

Philip Jeays - Victoria

Pennyblackmusic Regular Contributors

Adrian Janes

Amanda J. Window

Andrew Twambley

Anthony Dhanendran

Benjamin Howarth

Cila Warncke

Daniel Cressey

Darren Aston

Dastardly

Dave Goodwin

Denzil Watson

Dominic B. Simpson

Eoghan Lyng

Fiona Hutchings

Harry Sherriff

Helen Tipping

Jamie Rowland

John Clarkson

Julie Cruickshank

Kimberly Bright

Lisa Torem

Maarten Schiethart