Miscellaneous - Interview with Bruce Iglauer Part 1

by Lisa Torem

published: 5 / 11 / 2010

intro

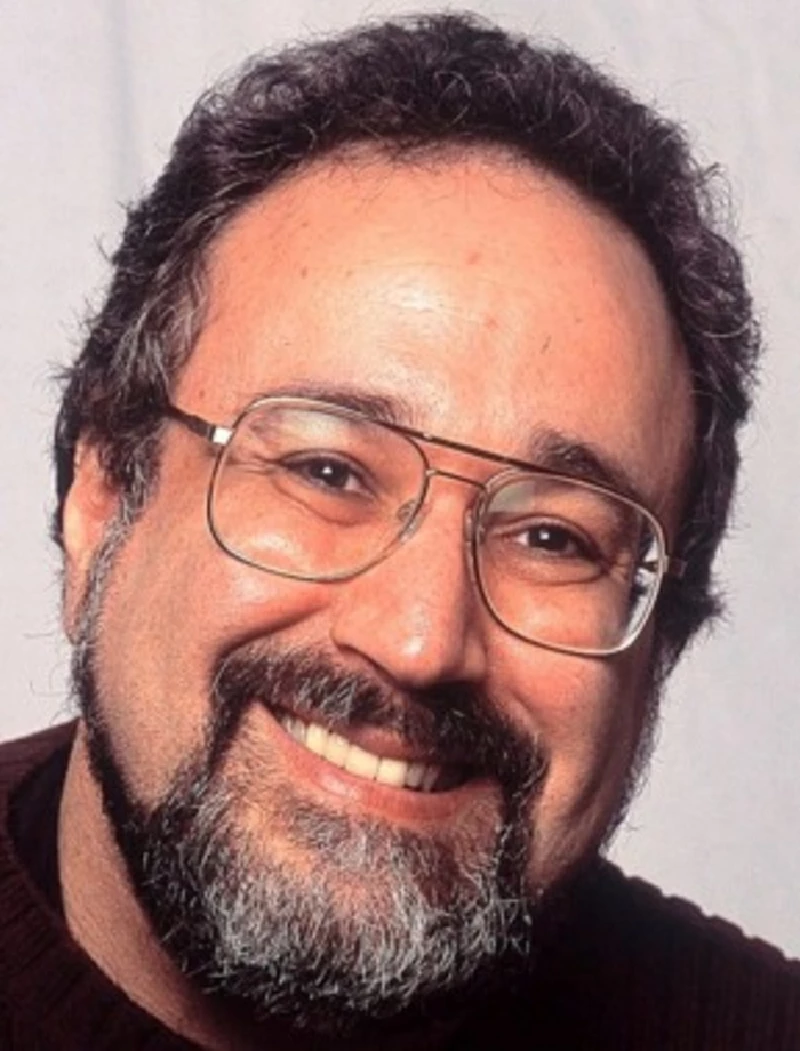

In the first part of a two part interview, Bruce Iglauer, the the president and founder of Alligator Records, the largest contemporary blues label in the world, talks to Lisa Torem about forming his label, which was first founded in 1971

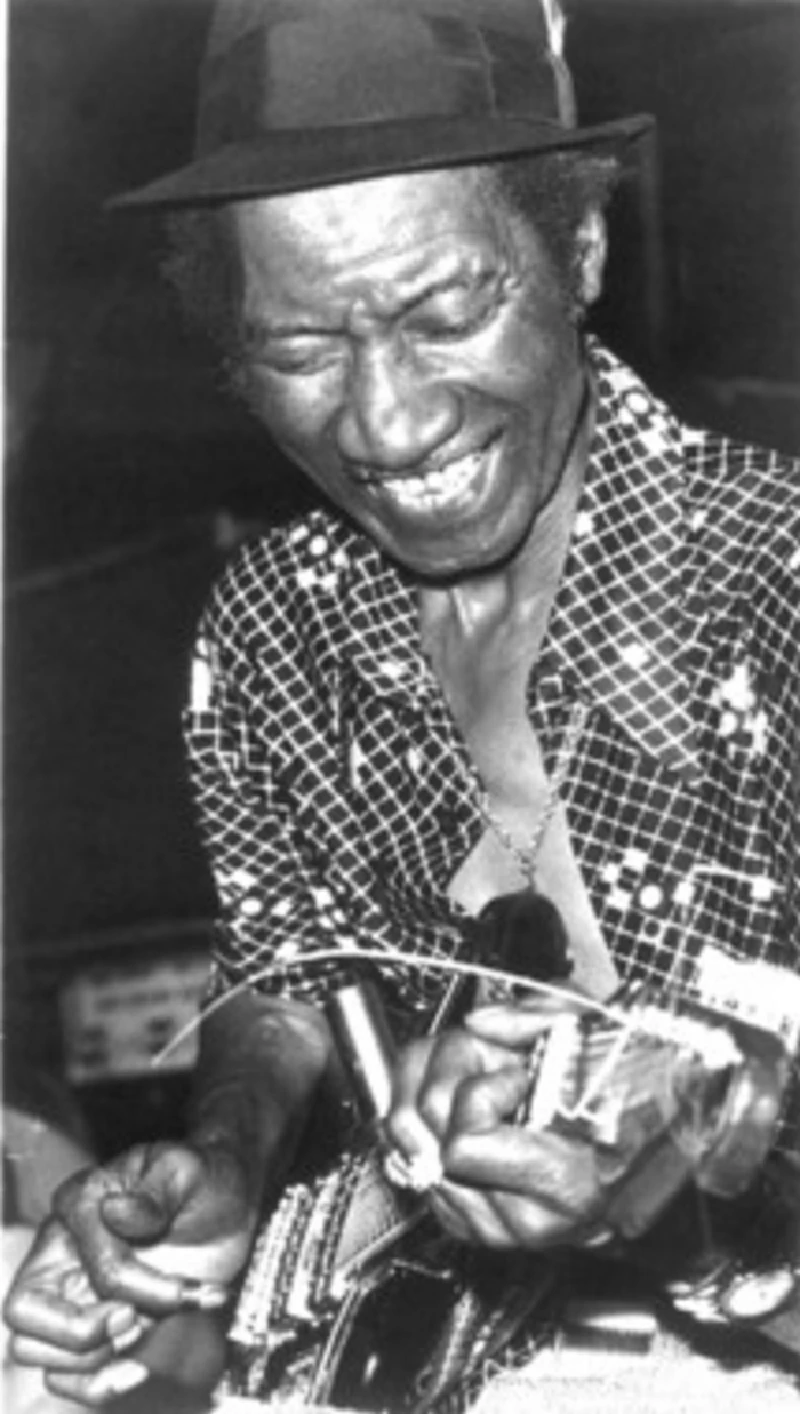

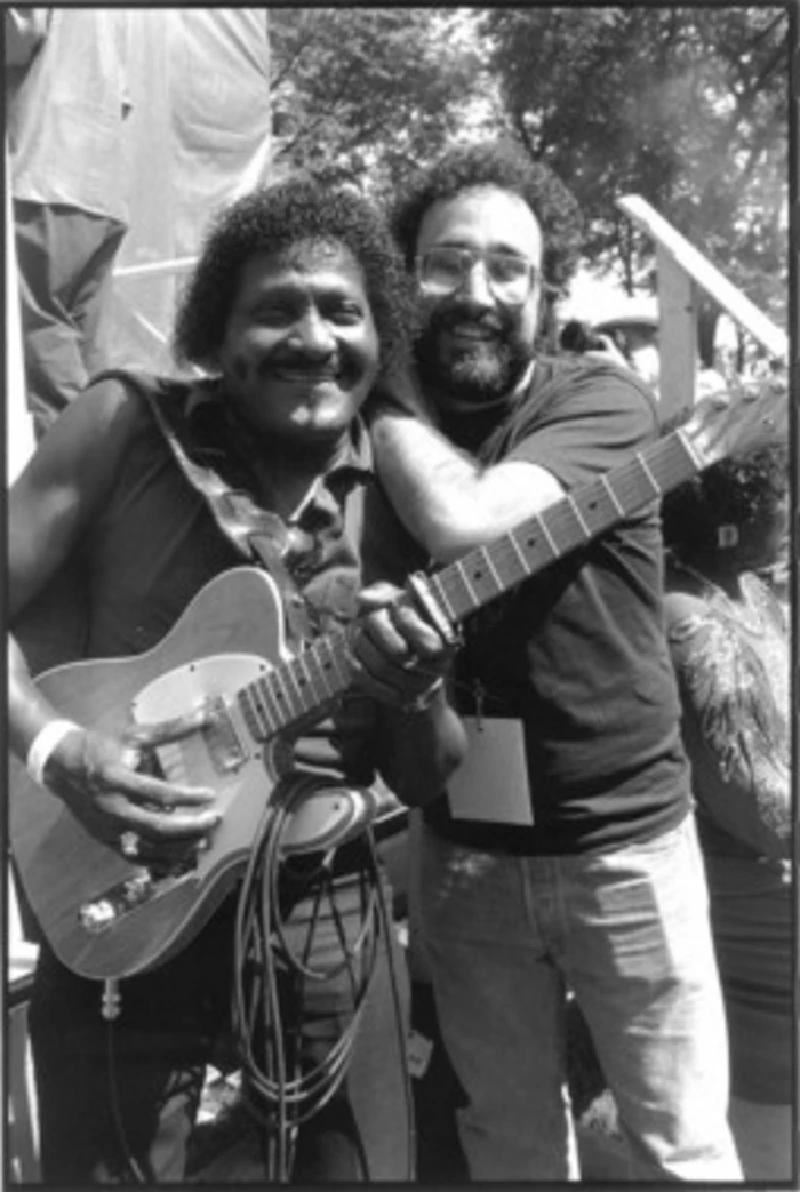

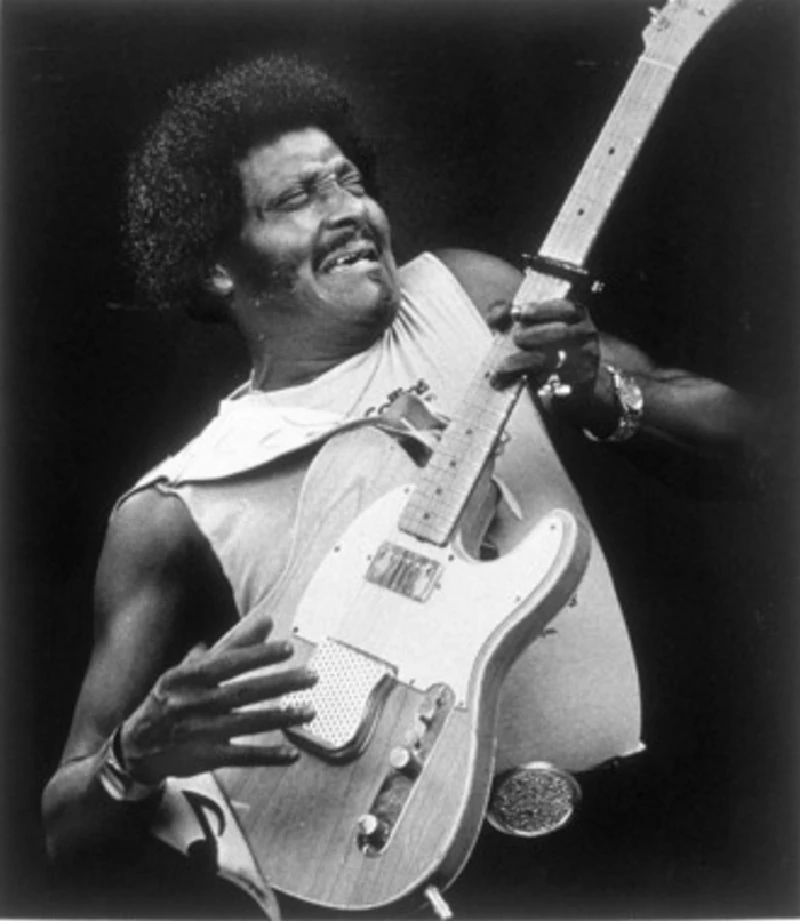

Bruce Iglauer, the president and founder of Alligator Records, the largest contemporary blues label in the world, founded the independent, Chicago-based label in 1971, operating it by himself from a one-room apartment. He was 23. Currently, Alligator’s catalogue contains over 260 CDs, over a hundred of which were produced or co-produced by Iglauer. His roster of artists includes recordings by Hound Dog Taylor, Albert Collins, Koko Taylor, Shemekia Copeland, Carey Bell, Saffire, Lonnie Brooks, Son Seals, Johnny Winter, and Roy Buchanan. Twenty six of the albums he has produced have been nominated for Grammy Awards, with one winner. Alligator releases have won dozens of Blues Music Awards, the highest award the blues world presents. Having acted as a booking agent, manager and road manager for “some of the greatest talent in the blues world,” Iglauer reveals, “I want to be remembered as the blues’ best roadie.” Alligator Records has managed the careers of many of the blues artists it has released, including Koko Taylor and Lonnie Brooks. Iglauer is also a co-director of the Blues Community Foundation, which supports blues music education and assists blues musicians and their families who are in need. In addition, he has served on the board of directors of A2IM, the American Association of Independent Music and its predecessor, the National Association of Independent Record Distributors and Manufacturers (NAIRD). He has also been a member of the Board of Directors of the Chicago Music Commission. He is also a co-founder of ‘Living Blues’, America’s oldest blues magazine. The Alligator label has won numerous awards, including a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Montreux Jazz Festival and an induction into the Blues hall of Fame in 1997. In 2002, ‘Chicago Magazine’ awarded Iglauer its “Chicagoan Of The Year” Award. In this exclusive interview with Pennyblackmusic, the impassioned Bruce Iglauer speaks to Lisa Torem about the joys, challenges and the history of Alligator Records, his dedication to the blues, how the recording industry has changed since the 70s and Chicago’s role in sustaining the blues as an important art form. PB: Bruce, you’ve run Alligator since the 70s. What have been the biggest challenges and rewards working with blues artists? What would make you drop an artist and how would an artist, without a track record, attract your attention? BI: When I began Alligator in 1971, there were two markets for blues recordings—the traditional African-American blues fans, who had grown up with the music, were generally informed about new recordings by hearing singles on black-oriented radio and often still bought 45s. They were a middle-aged audience who were very committed to the artists they had grown up with, like B.B. and Albert King and Bobby Bland. Some of the blues they liked was pretty “slick” by my standards back then, i.e. big production with horns, background vocals, sometimes even strings. Then there was the young, white blues audience who had discovered blues through folk music like I did or rock bands like the Stones or white bluesmen like Paul Butterfield as many of my friends did. These people bought albums, not 45s. They tended to be pretty ignorant of the breadth and depth of the blues (as I was) and also tended to respond to more rough-edged artists like Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf, who were more like rockers. This was the audience I came from and the audience I knew. I started Alligator shortly after the moment when rock first moved onto FM radio and there were “free form/progressive rock” stations that would play some blues in their regular format. So my initial huge challenge was to create a market and an audience for an unknown one-man, one record label with an album by an unknown artist named Hound Dog Taylor. My finances were so slim that if I didn’t sell enough of that first album, there would never be a second Alligator album. I pursued those free form radio stations as well as college radio, and all the rock press as well. As almost no one was promoting blues to these stations and magazines, I got quite a lot of airplay and press coverage. Based on that I was able to establish a network of distributors and make enough money to make the second Alligator album, by the great harmonica player Big Walter Horton, then a third by Son Seals, and each would pay for the next. It was a long time before I released more than one record a year. Since then, I’ve faced challenge after challenge—the tightening and whitening of rock radio, the vinyl shortage, the move from vinyl to cassettes to CDs to downloads, the growth of illegal downloading (now 95% of all downloads), the shrinking and dying of the retail stores, the death or absorption of most small record retailers and chains and the deaths of a lot of key artists. I’ve been doing this for 40 years, and I started with a lot of artists older than I was, so death has been part of the Alligator story for a long time. The biggest rewards of working with an artist are to see the public respond to the artists I’ve chosen for Alligator, either by experiencing a charismatic live performance by an Alligator artist, or by buying our music. And then are those magic moments in the studio when it all comes together and we create something timeless. I’m also very happy when my artists reach some kind of financial security. Recently one of my artists said to someone in an interview that Bruce Iglauer was responsible for the fact that he owned his own home. That felt pretty great. Alligator has become the most desirable blues label for an artist, and among the most desirable for a roots rocker. My unheralded staff and I have worked very hard for that. Why would I drop an artist? Two reasons. First, if the artist “doesn’t get it,” which can mean that he or she doesn’t want to play 60-150 gigs a year (which we need to establish and maintain their grassroots reputations) or doesn’t actively sell CDs from the stage, or doesn’t easily agree to do lots of radio or press interviews, which we also need. We feel we work on a team with our artists. It’s very, very difficult to establish and maintain careers in blues and roots music, and it’s very difficult to sell niche music. We work very hard for our artists’ gigs to be successful, and we expect them to work equally hard in presenting a great, exciting and soulful live show, and then selling CDs aggressively. We don’t have any 360 deals where we get a piece of the live performance income. Our whole income to support a staff of fifteen and pay out half a million dollars a year in royalties is from selling recordings and occasionally placing songs in movies, TV shows and advertising, plus some income from digital airplay via Sound Exchange. The artists primarily make their income from live performance, with hopefully some decent royalty income, depending on their sales. So they need our help in publicizing the gig, and we need their help in making the sales and being media-available. As I said, it’s a team effort. If the artist doesn’t understand and act on that, we all lose, and the artists don’t stay with Alligator. If the artist gets it, we will make a major commitment to the artist and try to stick with the artist through thick and thin. We worked with Koko Taylor for thirty five years, whether her career was flourishing or not. Many artists have been with us for ten or twenty years. To me, it’s like an extended family. I hope the artists feel that way. The second reason that we drop artists is the obvious one—lack of sales. As I said, we try to be very loyal to the artists who are loyal to us, but sometimes the sales are just too poor to justify putting out more albums. Then we hope that the artists get another offer from a legitimate label. Just because my staff and I believe in an artist doesn’t always mean that artist has a lot of public acceptance. There is no justice in this business. How would an artist attract my attention? By having a unique and personal musical vision, based loosely in the blues tradition, but not recreating what has already been done before. You’d be amazed how many demos I receive with Muddy Waters or Robert Johnson or Stevie Ray Vaughn songs, all done in an attempt to sound like the original. Not only does this show a complete lack of imagination and knowledge about the tradition (if you don’t have original songs, is there no one else to cover?) but how do you beat the original versions of these songs? You don’t. So I look for artists who understand the traditions but want to take them in their own directions. I need the artists to have an instantly identifiable sound and style. I always go to live performances as I need artists who can really communicate their music to a live audience. We can’t count on much commercial radio or major media coverage, though we work hard to get it. We have to depend on the strength of the artist in live performance as our best selling tool. And I need artists who “get it” about working with us in a team effort, as I described above. I have a wonderful roster of artists who are smart, motivated and can absolutely kill in live performance. Our current artist lineup is: Marcia Ball, Lonnie Brooks, Buckwheat Zydeco, Michael “Iron Man” Burks, Tommy Castro, Eddy “The Chief” Clearwater, James Cotton, Tinsley Ellis, Rick Estrin and the Nightcats, JJ Grey andMofro, Guitar Shorty, the Holmes Brothers, Smokin’ Joe Kubek and Bnois King, Lil’ Ed & The Blues Imperials, Janiva Magness, Charlie Musselwhite, Anders Osborne, Roomful of Blues and The Siegel-Schwall Band. PB: You initially came to Chicago to work with Bob Koester, the Jazz Record Mart owner and Delmark Label founder. What knowledge did you acquire from working with Bob and how did that experience sharpen your vision for Alligator? BI: Bob is a great hero to me and should be to everyone who cares about blues and jazz. He has followed his own ears and his own vision, making records of artists he believes in, since 1955. He’s recorded great bluesmen like Junior Wells, Magic Sam, Big Joe Williams, Roosevelt Sykes, J.B. Hutto, Carey Bell and many dozens more, as well as groundbreaking jazz artists. Compared to Bob, I’m a newcomer. Bob was my guide to the ghetto blues clubs in Chicago in the late 60s and early 70s. He had already won the respect of many of the blues artists, so when I went with him, I was considered “Bob’s kid” and bluesmen like Junior Wells looked after me. I was with Bob in the studio a lot, and mostly as the “gopher” would go for food, drinks etc. I watched Bob work with artists as often as I could. He generally gave the artists full control of their sessions, including picking all the sidemen and songs. This worked well with the right artists and when a lot of standard Chicago blues songs weren’t so widely known, and made for albums that felt a lot like club gigs, which meant a great vibe but also sometimes more musical looseness than makes for a memorable repeated listening experience. Bob loves making records, but doesn’t enjoy or dedicate himself to marketing them. He sort of released a record, sent out a few dozen promo copies, and then waited to see if anything would happen. He didn’t promote or publicize artists’ live performances, nor did they expect him to. It wasn’t his way of doing business. So Bob’s goals were more to make records than to build the audience. But he has a great ear for talent and he made many classic albums that will live forever. When I started Alligator, I wanted to make albums as good as Bob’s best, but also wanted to do a little more planning in advance than he liked to do, including wanting to have a series of rehearsals, make sure that everyone in the band could carry his own weight (sometimes the road band is made up of those people whom the leader can afford and will show up and want to go on the road; it isn’t always the best or most sympathetic musicians for the studio), and to avoid well known songs. As time went on, I became more and more of a producer, partly because the vocabulary of the blues became better and better known and I wanted to encourage artists to create more new songs, push them for less traditional arrangements, and in general tried to get the artists to challenge themselves and make blues that would speak to a contemporary audience. But the main thing that distinguished my business concept was that I wanted to turn new people on to the music I loved, spread the word, and make our artists and the blues overall more popular. I had a vision of how to do this, and I started at the right time, when rock radio was at its loosest, and also with the right artist, Hound Dog Taylor, whose raw, tough sound spoke to some of my generation. But let me be clear—without Bob Koester there is no me and no Alligator Records. He opened the door and I walked through it. PB: One of your first experiences working with Bob was getting a few blues artists out of jail. How much of your job entails dealing with personal issues that come up? BI: Yes, at my very first recording session my first job was to drive to the South Side and bail out the bass player and drummer. They had been stopped for running a red light and the driver didn’t have a license, so they were all arrested. They even locked up the drums. So one of the first things I learned when I came to Chicago was how to find the police station at 51st and Wentworth. For years, I ran Alligator first out of my apartment and then out of a small house that I was able to buy. I live there now but I knew we had to move when there were 7000 cassettes being stored in the kitchen and the basement was packed to the ceiling with LPs. At that time, every one of my artists knew where I lived, of course, and I didn’t even have a home phone. I just used the Alligator phones. Since we moved to a small building, all the artists have my cell number and don’t hesitate to use it. Sometimes they will call when they run out of CDs on the weekend and need an emergency shipment (this happened moments ago). Other times they will call when the van breaks down on the road, so I can rent something by long distance. Sometimes the calls are much more personal. I talked at length recently with an artist whose marriage was falling apart. I counseled another artist who had gotten into a physical fight with a member of his family and was feeling awful and needed a friend. One of my artists was arrested a couple years ago on a non-violent, non-drug-related charge and I spent all day at Cook County Jail arranging his bail, then took him to my house (he was from out of town) where he spent the night before I put him on a plane home and then hired a lawyer for him. And it happened that day was my birthday. Once an artist who was trying to stay clean and sober came and lived at my home for a while. He needed a friend and turned to me. Other times artists come to me to discuss band politics, hiring and firing, their relationships with their booking agents or manager, or their tour plans. I consider these things to be a normal part of my role. As I said, I see Alligator as sort of an extended family. That’s fine with me. I think family is who you choose them to be. Some terrific, talented people have chosen me to be family and I’ve chosen them. I hope some of them will be friends for the rest of our lives, regardless of our business relationship. PB: In the 1970s, after Chess Records started facing financial difficulties, you signed blues vocalist Koko Taylor, a former Chess client, who had already recorded the successful Willie Dixon hit, ‘Wang Dang Doodle’.’ With Alligator, Taylor recorded ‘I Got What It Takes’ in 1975, and received her first Grammy nomination. How did that happen in such a relatively short amount of time? BI: A lot of people compare Alligator and Chess, but other than both making (I hope) great blues records, there isn’t much of a comparison. Chess was mostly about making singles of blues and R&B, and later rock ‘n’ roll, and making them into radio hits, whether on black-oriented radio or later on rock and roll Top 40 radio. Alligator was and is all about albums and doesn’t expect a lot of radio play (though we work hard to get AAA play on our artists who fit that format). When I started, Chess had been sold and Leonard Chess had died. Blues was no longer very popular on black oriented radio and rock radio had that short period of time when they would play some blues. So my timing was really good. Koko had been dropped by Chess as she wasn’t a consistent hit maker on black radio. They had released two albums by her, produced by her mentor and friend Willie Dixon, but neither was a commercial success. Koko was working as a single artist, as a guest with various bands including our mutual friend Mighty Joe Young’s group. She was not really a famous artist; in fact, she was working a day job and singing at night. So, like many great blues artists at that time, she was a totally unsigned free agent. In fact ‘I Got What It Takes’ was not a successful album in terms of sales. The album that really launched Koko’s career on Alligator was the next one, ‘The Earthshaker’. At this time, there were so few nationally distributed blues records being released that every one was sort of an event. PB: Chicago’s then mayor Richard M. Daley declared March 3, 1993, Koko Taylor Day. What about declaring additional days for blues artists? BI: I believe that the mayor has declared other days for blues artists over the years, as well as having some streets receive ceremonial names for blues artists (as well as other prominent Chicagoans). Unfortunately, there are no commemorative markers for buildings (or vacant lots, as many are) that were the sites of famous blues clubs. The city has done a good job with presenting a very large and free blues festival every summer for over 25 years. Unfortunately, the funding for this and all the free Chicago summer festivals is threatened this year as the city is so broke. Also unfortunately, the city has been less supportive of live music clubs in general, often giving them a lot of problems about compliance with very complex and contradictory regulations. The exception is Buddy Guy’s ‘Legends’, which has received support from the city especially in moving to its good new location. PB: In your opinion, could the city do more in terms of creating a blues mecca in Chicago in general? BI: Yes, it could. The city government doesn’t recognize the cultural value or touristic value of its music scene. It could learn a lot from Austin, the so-called Live Music Capitol of the World (which has a lot less live music than Chicago). Austin presents live music at the airport, on the steps of City Hall, has helped musicians get health insurance and has been generally very supportive of its club scene. Seattle has cut taxes on live music performance tickets and even has local music on hold when you phone City Hall. I’m hopeful that the next mayor may see the value in nurturing the music club scene, not just for blues. PB: In Memphis, free shuttles take tourists from Sun Studios to major music-related museums throughout the day and the Beale Street area hosts restaurants and clubs all supporting the blues theme. Why can’t Chicago be more like Memphis? BI: You’re asking the wrong person. I agree. PB: Also, Willie Dixon and his family had opened up the Blues Heaven Foundation site to commemorate the history of blues artists, yet it’s only known to an esoteric group. What would it take to get the blues scene more acknowledged by urban planners and mainstream radio? BI: Mainstream radio is a commercial business. It isn’t their job to support local culture or music; it’s their job to get ratings and sell advertising. Chicago has the odd situation of having only one city-wide public radio station in WBEZ. They do a fine job with talk and news but have decided consciously to virtually eliminate music programming. Most other major cities have multiple public radio stations that are heard over the whole city. This situation isn’t anyone’s fault; it has to do with the fact that all frequencies in Chicago are owned, so there is no way to set up a new station here, unless HD radio allows more frequencies to be available. Of course as internet radio and satellite have become popular, local radio may have less effect, but it sure would be great to hear local music supported on local radio. There is more blues on the radio city-wide in Atlanta, San Francisco, Houston and dozens of other cities than in the so-called blues capital of the world, Chicago.

Picture Gallery:-

most viewed articles

current edition

Carl Ewens - David Bowie 1964 to 1982 On Track: Every Album, Every SongArmory Show - Interview with Richard Jobson

Colin Blunstone - Thalia Hall, Chicago, 16/7/2025

Bathers - Photoscapes 1

Visor Fest - Valencia, Spain, 26/9/2025...27/9/2025

John McKay - Interview

Billie Eilish - O2 Arena, London, 10/7/2025

Robert Forster - Interview

Sir Tim Rice - Interview

Loft - Interview

previous editions

Heavenly - P.U.N.K. Girl EPManic Street Preachers - (Gig of a Lifetime) Millennium Stadium, Cardiff, December 1999

Beautiful South - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

Pixies - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

Oasis - Oasis, Earl's Court, London, 1995

Paul Clerehugh - Interview

Prolapse - Interview

Trudie Myerscough-Harris - Interview

Doris Brendel - Interview

Peter Perrett - In Dreams Begin Responsibilities Interview Part One

most viewed reviews

current edition

Phew, Erika Kobayashi,, Dieter Moebius - Radium GirlsAmy Macdonald - Is This What You've Been Waiting For?

Sick Man of Europe - The Sick Man of Europe

Davey Woodward - Mumbo in the Jumbo

Alice Cooper - The Revenge of Alice Cooper

Lucy Spraggan - Other Sides of the Moon

Blueboy - 2

Cynthia Erivo - I Forgive You

Suzanne Vega - Flying With Angels

Bush - I Beat Loneliness

Pennyblackmusic Regular Contributors

Adrian Janes

Amanda J. Window

Andrew Twambley

Anthony Dhanendran

Benjamin Howarth

Cila Warncke

Daniel Cressey

Darren Aston

Dastardly

Dave Goodwin

Denzil Watson

Dominic B. Simpson

Eoghan Lyng

Fiona Hutchings

Harry Sherriff

Helen Tipping

Jamie Rowland

John Clarkson

Julie Cruickshank

Kimberly Bright

Lisa Torem

Maarten Schiethart