Gang Of Four - Interview

by Lisa Torem

published: 8 / 11 / 2016

intro

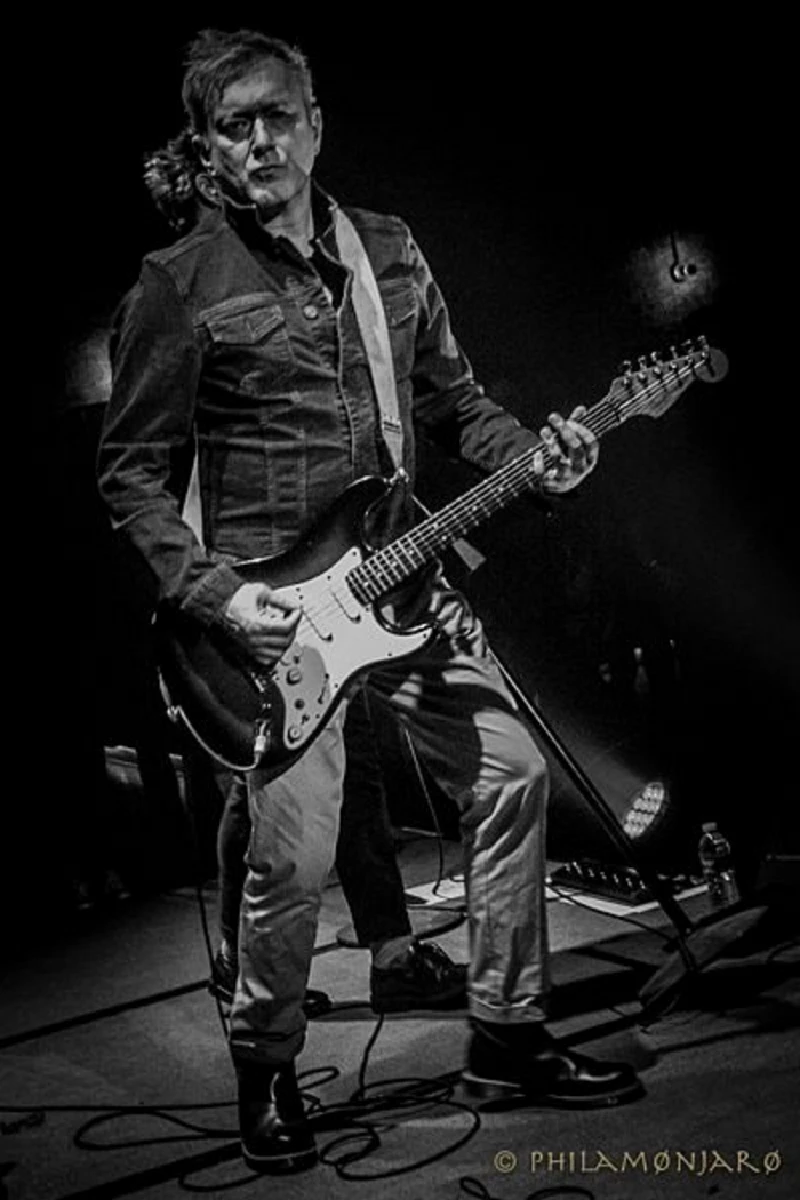

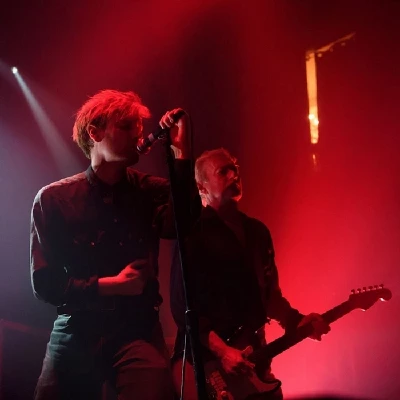

Andy Gill, frontman, co-founder and only remaining original member of British post-punk band, the Gang of Four, speaks to Lisa Torem about new multi-media project ‘Live..In The Moment’ as well as his vast experience as a producer, guitarist and arranger

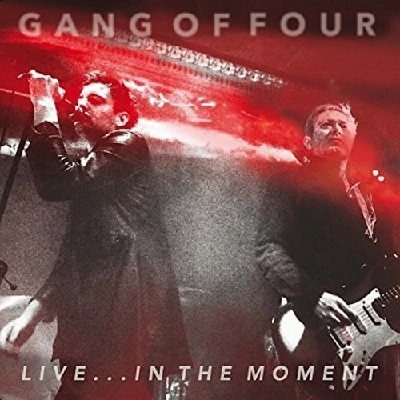

Manchester-born Andy Gill formed the ‘Gang of Four’ in Leeds. The current lineup consists of vocalist John Sterry, bassist Thomas McNiece, drummer Jonny Finnegan and, of course, Gill, the multi-talented producer, songwriter, conceptualiser, lead guitarist and only remaining member of the legendary post-punk band. The band rose to fame in England with the release of 1979’s ‘Entertainment!’, on which their stark, apocalyptic vision stirred the sensibilities of restless youth. The excitement and rebellious inflection continued on with 1981's ‘Solid Gold’ and the following year’s epic ‘Songs of the Free’. The band parted ways in 1984, but burst back onto the scene with ‘A Brief History of the Twentieth Century’ and ‘The John Peel Collection’. In the early ‘90s, the rogues segued into a danceable zeitgeist, before re-embracing Gillesque virtuosity. Although the original group members came back together for a brief tour and the recording of ‘Return The Gift’ in 2005, they wouldn’t return to the studio until the release of 2011’s ‘Content’, which ushered in vocalist Jon King’s departure. Last year’s ‘What Happens Next’ enjoyed the talents of multiple guest artists and was the first album to feature vibrant vocalist John Sterry, whose live gifts include convulsive dance moves and whose sonic palette includes clipped phrasings and an uncanny ability to sing in tandem with Gill over his exuberant electric guitar. More recently, the Gang of Four have released ‘Live…In The Moment’, which features a DVD performance of two live performances of classic and newly penned material as well as remastered recordings. Gill says about Sterry’s treatment of the tracks: “They’re dynamic. They’re emotional”, and about the selection of material: “I quite like the way the songs sit next to each other; older things with the recent.” Gang of Four’s influence cannot be understated. Their live arrangements incorporate bold theatrics, ghoulish spoken word, and blowtorch bass lines. They demand and receive explosive interaction internationally. The late Kurt Cobain as well as members of Rage Against the Machine and The Red Hot Chili Peppers have expressed their gratitude. On stage, Gill may appear to be the quintessential musical sphinx. The band’s storied material may be rendered through monotone or gyrating effects. Gill may be heard whispering in the background or gasping for breath in tandem with singer John Sterry as they boxstep through ‘Damaged Goods’. The act may conjure up ancient Noh traditions or cacophonous street hustle. They will not leave you unmoved regardless of whether the sound du jour is a bewildering, stone-faced silence or a rainstorm of electric hysteria. And it was Gill who fired off the very first pistons and still keeps the GOF engine (remotely) clean. In his first interview with Lisa Torem at Pennyblackmusic, Andy Gill talks about the Gang of Four’s impressive endurance and legacy, the challenges of being a producer and perpetual multi-tasker and why he’s partial to smoke and mirrors. PB: What prompted the recording of ‘Live…In the Moment’ at this moment? AG: John has been singing in the band now for about three years since the first gigs he did. And it also struck me, I’m kind of going off on a tangent, but the way that I kind of work is, I work things out in the studio, I sort of demo them a bit and people add to them and I don’t really say, “That’s that, let’s go and play this as a band” and then record it. I might start and stop again, but very often on the records, and this has always been the case, they’re not necessarily songs that have been played live and they go through that subtle change once they’ve been played a bit live, so that was one aspect of it. Sometimes you think, what’s happening here sounds a bit less studio and a bit more organic and there’s bits of some expressiveness that’s coming into certain aspects of it that wasn’t there in the original recording. It’s a different take on it and a more lived-in production and also getting John’s live performance down was another thing. The only live record was done in 1984 and it was a very different incarnation, so it did feel to me like it was pretty much long overdue. PB: And why did you choose New York and London shows? AG: That just turned out to be the way it was, really. When we were in New York, it was filmed and there were several cameras and so we had that footage and a friend of mine is a film person, so that was it. And the London thing? The Assembly Hall in Islington is set up with the recording; they’ve got everything there. It’s literally become a practicality. I might have preferred recording somewhere in America, but it’s just kind of the way it turned out. PB: You refer to 'Why Theory' as a “feminist masterpiece.” AG: A, I’m a bit cheeky and B, it’s obviously the way I think. To me, at the core of feminist thought is the idea that much of the way we opt and much of the way we behave is through taught ideology. We’re kind of taught that women should stay home and take care of babies. We’re taught that. There’s nothing particularly natural about that. When people say that that’s the natural way of being — using that word, “natural’, it’s a catch-all to hide that argument about what’s nature and what’s been taught. I think a lot of what we think is the way it is... it starts there, it’s ideological. And when we went on tour in the States, in 1980 or 1981, I had this feminist pamphlet and it was called ‘Why Theory’ and I got it from somewhere or other — it was literally a little pamphlet, just a few pages long and it ended up in my luggage, so the expression came from that. PB: Let’s talk about ‘What Happens Next’. ‘Where The Nightingale Sings’ begins with an excerpt of a Robert Johnson song from 1937. What does that say about your influences? AG: I’m not one hundred percent sure why I put that on the beginning. It just sort of felt right. There are a lot of things that have informed the way I think about music and how I approach it. I think most people wouldn’t look at Gang of Four and listen to the music and go, “Oh, I can tell there’s a blues influence in there.” I think very, very few people would say that, but some people do pick up on it. People have written that that song, ‘Paralysed’, is essentially a blues, and it’s not until you think about it that you see it is, because stylistically there’s nothing bluesy about Gang of Four, not obviously anyway. In Leeds, I moved into this horrible flat in a basement and whomever had been there before had left a few bits and pieces and there was a Muddy Waters record. I think it was called, ‘The Best of Muddy Waters’— it was vinyl, obviously, being in the ‘70s and I played it to death and I think one of the things about it was, its incredible simplicity, incredible sparseness. I guess there was one microphone in the room, maybe two, but I think one. You can kind of hear the sound of the leather of his shoe on the floor, because of the space and because he’s not doing very much on the guitar; he’s not doing very much at all, you can sort of hear the air and it’s kind of electrifying. That’s one of those things where, if you had to prove to someone why vinyl is better than CD, that would be the record… Whatever that noise is that vinyl makes, even when it’s a good disc, there’s something that’s in there and that was a record that I really loved. I didn’t hear Robert Johnson until later on actually. I heard Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf and a bit later on I heard Robert Johnson, it’s really raw and it’s got a really primitive vibe to it that is so exciting. PB: You write “Turn your back on London’s bitter pride and melancholic isolation” in ‘Nightingale’, and then in ‘England’s in my Bones’ you present a much more positive picture of your native country. Does that represent a dichotomy in you? A love/hate? AG: ‘England in my Bones’ again is kind of mixed because it’s a mash up between William Blake’s ‘Jerusalem’; that line: “Bring me my bow of burning gold / Bring me my arrows of desire”. So when he was writing that in England, it was at the beginning of the Industrial Revolution in England and he saw the black smoke billowing out of the factories. He saw the beginnings of the industrial alienation of the people that were going into the mills— “the dark, satanic mills.” And then he’s looking back to an imagined time of when, in his words, “Jesus is walking the land.” And I’ve got teenage girls sex texting guys in there, and what exactly have they got apart from that? So I wouldn’t say it’s entirely an optimistic, rosy view of the old country, but I think with ‘Nightingale’--the kind of general idea is that comparison with urban life and that outside of London, the towns are very, very different places and with very, very different kinds of thinking. I mean, obviously, it’s the same thing in America, people think pretty differently outside of Chicago, but it sort of has consequences. The people that don’t like Johnny Foreigner and voted for Brexit, they don’t live in London. So I’m talking about the mythology of that perfect countryside where everybody knows each other’s names and every door is open because no one is going to come in and steal anything. And it’s all bollocks and it all leads to, and there’s a sweeping statement here — it leads to Fascism, you know. PB: One of the newest songs is ‘Isle of Dog’. The lyrical hook, “Let forgiveness be heard, I can change”, is all the more riveting because of John’s vocal performance. Is it my imagination or do I hear some Elvis channelling? And, also, what was your expectation of how that song would sound live? AG: Elvis? I quite like that. In the sound of his voice? PB: Yeah. I think we traditionally associate Gang of Four with a post punk texture, but there’s undoubtedly a ballady feel to this one. John’s quite the crooner here and I believe it really stood out for that reason. AG: Early Gang of Four lyrics are quite chanty and quite abbreviated and I like that because it was always the case and always the intention that the vocals should sit alongside the hi-hat and the snare beat and the rhythm of the kick drum and all of those were supposed to work together, and I still feel like that very much but I also want the vocals to be as expressive as they can as well and use the things that are available to a vocalist, like vocal dynamics and vibrato and all of those things that can help bring meaning over and above the lyrical content if you like, or to expand on the lyrical content in a way. PB: ‘Anthrax’ is a Gang of Four classic with a one-off arrangement. Was it challenging for John to adapt to this kind of unique material? AG: It’s quite an amazing thing about the way he came into it all. I felt like I didn’t have to explain anything to him. He’d say, “Let’s have a go at this song” and we’d never done it before. He’d get a few things wrong, but it was amazing how much he got things right. He just got it, even the other stuff that was written before he was born. He understood it pretty much straight away. PB: ‘Paralysed’ really shows off your shredding expertise. Every day, of course, thousands of guitarists strive to come up with a new sound, a new style. Can you explain how you have come up with yours? More specifically, how does your mind process everyday sounds? AG: That’s a clever question and I’m not 100 percent sure how to answer it. I sometimes think the guitar should be a bit like an abstract painter, Franz Kline, or someone like that, when they make marks on the canvas. Sometimes they’re kind of reinforcing the geometric structure of it and sometimes they’re working against it and destroying it. I think of a guitar a bit like that. Sometimes the guitar is a noise instrument and it’s generating noise which is sort of smeared over the fabric of the rhythm, and sometimes it’s quite staccato and very, very, tightly knit with the rhythm or playing a part within that rhythm and it sort of alternates between the two. I’ve always thought of it like that, there’s a very kind of free Hendrix sort of noise thing, which isn’t hugely rhythmic; it just kind of exists and is there or it’s underground, where there’s feedback and noise and stuff, and then there’s stuff written on guitar by Steve Cropper or his later incarnation, Niles Rodgers; all that kind of tight funkiness. I kind of lunge into those things, I kind of incorporate both of those. I think you’re right, the sounds that you hear around you, they do feed in, in a way and I’m not quite sure how that happens, but I think that it does happen. Sometimes people ask, “What would you advise me to do?” And I think I would say, ‘Don’t just think about music when you’re thinking about music. Think about the conversation you had on the tram and think about the extraordinary banality of the commercial you just saw on TV. Think about the thing that inspired you about the film.’ Because if you’re just looking to other music, it narrows things down rather than opens them up. PB: A member of Ok Akubo, a band which you have produced, mentioned that he was surprised that you spent a lot of time with the percussion tracks when in the studio. The thought was, Andy Gill is a guitarist. What is your philosophy about production? AG: I think Steve Albini is a great producer, but he’s kind of the opposite of me. He’s sometimes said that he doesn’t consider himself a producer. He considers himself an engineer, so he will spend a lot of time placing the microphones and then getting the band in the mood and then getting that performance and then capturing sound. But I guess I’m more dishonest than that and I’m very happy to use smoke and mirrors. If I can make something more rhythmically grabbing and more effective by working with some sort of click of some sort and maybe editing the drums, they’re pretty tight with that, and if that’s going to make a better result then that’s what I’ll do. With Jesus Lizard in Chicago, we spent about three months doing their album in Chicago in 1997 or something and we worked on the drums a lot and they knew all the songs really well. They’d done their aspects of it and they are brilliant in their arrangements, so we might sit down and tweak the arrangements a bit, but we kind of knew where we were going and then I just felt I was going to get the whole thing, because those guys are kind of like a machine: the bass, the drums and guitar. When you see them live, it’s quite mechanical. David Yowls is really sloppy, but they’re really very tight. I think it is a good idea to play your songs, not necessarily live, but to play them as a band, and preferably live as well and to kind of work out a few nuances before you then go in and get a tight performance. PB: Do you find scoring music to be as rewarding as playing live? Is it challenging, for example, to condense your original material and synch it up in a set format, according to another person’s vision? AG: I think it’s very different and it’s been a while since I’ve done it, but I find it enormously enjoyable. Having an image to work with is different, but I love it. That’s not so different from producing a band where you’re kind of trying to find some common ground. Every band I work with—they have their ideas, they have their ways of going about things, they have stuff they’re looking for and it wouldn’t be where I would go if left to my own devices, so I have to be into where they’re coming from and understand the difference between what they’re doing and what I would do and then see what I can bring to the arrangement. So it is like seeing somebody else’s vision and then working with it. The Michael Hutchence stuff that I did years ago? When I co-wrote all of those songs with Michael? They may be getting revisited for another release. (LT: Michael Hutchence and Andy Gill began their collaboration in the spring of 1995. Andy Gill co-produced the self-titled ‘Michael Hutchence’ solo album and co-wrote several songs. Hutchence died in 1997.) I’d been a great admirer of his vocal style, but didn’t particularly love INXS, but I thought what he was doing was fantastic and I loved his voice, so he had said, ‘Do you want to co-write a bunch of songs?’ and I thought, fantastic. I was bringing my guitar and my guitar approach and then working with his ideas. It’s definitely a bit more of a poppier angle than I would be known for, but I enjoyed it very much. PB: You tend to draw a multi-age audience. Some know the Gang of Four lyrics by heart and some don’t seem to care what the theme is, they simply want to dance and haven’t done their homework. Given that many songs stem from a deep political consciousness, is that okay with you? AG: Yeah, 100 percent. And that’s always my opinion. It’s not as if you’re there to preach or whatever and your congregation had better know their lines (Laughs). God forbid, to follow the religious analogy. The groove is every bit as important as whatever the lyrics are. PB: ‘At Home, He’s A Tourist’ and ‘I Love a Man in a Uniform’ were once considered controversial by the BBC. You guys stood your ground on that. How does it feel to think back on those days, considering anything goes these days? AG: When that little piece of history comes out, people are kind of like, "What? Run that by me again. You did, what? You walked off the show?" But the whole fact that the producers would say, "You can’t use that lyric. You can’t mention contraception." It’s quite jaw dropping, these days, isn’t it? I think it was partly the case that they were trying to find a reason not to have us on the show because they kind of hated us, but back then there were rules about, if a single had gone up a certain number of places in a week, you had to put them on. It was a rule to make it a more neutral playing field, so they weren’t very happy about having to have us on, but being the very obstinate bastards that we were — but we did play along a bit. They said, “Change the word,” so we did change it to “packet.” We went around the corner and rerecorded it and changed it to “packet” and then we came back and they said it’s not good enough, we want you to change it to rubbish so that it sounds like rubbers so that you’ll be complicit in covering up our censorship, which just seemed a step too far. So there we go. PB: It’s part of the legacy. AG: And I’m sure we would have found lots of other opportunities to fuck up our career after that. PB: Who would be your dream co-songwriter, living or dead? AG: I was always a little hurt that David Bowie never called me up. A lot of the stuff he did was definitely influential on me. The way he approached coming up with stuff was really clever. He would have been a great person to write with. Kanye West. Not the last album, but the one before, ‘Yeezus’. Some of the album is not very good, but it’s got two or three brilliant songs. One is called, ‘Can’t Hold My Liquor’ and it’s a very clever and a very strange and unusual song. I guess he doesn’t really work with guitarists, but then I can always program the drums for him or something. PB: Rolling Stone magazine wrote that Gang of Four’s debut ‘Entertainment’ was “A genuine revolutionary force in the pursuit of working-class justice.” Does that apply to how you feel now about your music? AG: It’s always a slightly funny one, the Gang of Four politics things. It’s going back to what we were saying at the beginning of this conversation. The songs like, ‘Natural’s Not in It’ and ‘Why Theory’, okay, that’s on the next album, but the songs like ‘Natural’s Not in It’ and ‘History’s Not Made by Great Men’, they’re not exactly a call to arms, are they? But they are basically saying, “Look, look around you. You’re being told all this stuff is the way it is and this is why you’ve been told this is why it is.” I suppose, in a sense, it’s genuinely radical and it is in a profound way political. It’s not party political. It’s not saying you should vote this or you should vote that or this is what you should believe. It’s almost like the opposite of this is what you should believe. This is why you’re being told this is what’s true and these are the mechanisms and you do what you want with that information. PB: How did you come up with that rooster call on ‘To Hell with Poverty’? AG: You mean that, ‘Eh, eh, eh, eh’? I’ve never thought of it as being a rooster (Laughs). That’s an interesting idea. That was a Jon Kingism. I remember often having conversations with Jon about, there is that thing in songs where there’s just kind of ‘oh, oh, oh’ sounds or ‘ah, ah, ah’ sounds— ‘Sympathy for the Devil’ where they’re going, ‘ooh, ooh, ooh’, and I was always looking for some of that and Jon King would always knock it down. “That doesn’t mean anything, it’s just noise…” And that was one of the situations where I kind of got my way, a “just noise” vocal part. PB: Generations later, the crowds still love that kind of thing so much. Does that surprise you? AG: I think they’re well-built songs and they’re not dependent on the sound of their day. Some songs you hear them and they sound so ‘80s because of the sound of a drum machine or something, but because it’s sort of stripped down and it’s got a guitar and bass, you can’t really tell what time it’s come from and I think that’s part of it. I don’t know. PB: Can you describe your current state of mind? And this can be musical, nonmusical? AG: I’m trying to spend some more time in the studio because I’m working on some new songs. and I’ve gotten to that point where ideas are coming faster and I’m frustrated because I have to spend so much time on my laptop answering emails, designing stickers for the album, shirts, who is going to post the CDs? Where are they going? So that I can sign them. The list is about four yards long and somehow it doesn’t matter what I do--the more people I get in to help me, the slower it seems to go. So it’s a little bit frustrating that one spends a lot of time doing that stuff and not doing the things that you want to be doing. PB: Thank you. Photos by Philamonjaro www.philamonjaro.com

Band Links:-

http://gangoffour.co.uk/https://www.facebook.com/gangoffourofficial

https://twitter.com/gangof4official

Picture Gallery:-

profiles |

|

'Songs of the Free'/'Hard' Profile (2008) |

|

| Anthony Strutt examines Gang Of Four's third album from 1982, ‘Songs of the Free’, and fourth album from 1983, ‘Hard’, both of which have been recently reissued |

live reviews |

|

Borderline, London, 12/4/2019 |

|

| Adrian Janes watches influential post-punk the Gang of Four in a show at the Borderline in London play a fiery set to promote their new album 'Happy Now'. |

| Metro, Chicago, 30/9/2016 |

| Macbeth,London, 24/8/2009 |

reviews |

|

Live…In the Moment (2016) |

|

| Praiseworthy new live CD/DVD from seminal UK post-punk outfit, the Gang of Four |

| Second Life/Paralysed (2008) |

most viewed articles

previous editions

Cindy Smith Dunaway - InterviewAlice Cooper - 50th Anniversary of the Alice Cooper Group Original Line-Up Celebration Part 2

Bram Tchaikovsky - Profile

Slow Readers Club - Manchester Cathedral, Manchester, 4/5/2018

Miles Kane - Academy, Manchester, 23/11/2018

Black Peaks - Photoscapes

Harold F. Eggers - My Years with Townes Van Zandt: Music, Genius, and Rage

Andy Whitehouse - Interview

Asian Dub Foundation - Rafi's Revenge

Peter Doherty and The Puta Madres - Ritz, Manchester, 9/5/2019

most viewed reviews

current edition

Lapsley - I'm a Hurricane, I'm a Woman In LoveBlueboy - 2

Davey Woodward - Mumbo in the Jumbo

Philip Jeays - Victoria

Eddie Chacon - Lay Low

Suzanne Vega - Flying With Angels

Taylor Austin Dye - Sick of Me

Only Child - Holy Ghosts

Nigel Stonier - Wolf Notes

Cynthia Erivo - I Forgive You

related articles |

|

Gary Numan: Live Review (2014 |

|

| In front of an exuberant crowd, Adrian Janes watches 80's icon Gary Numan, with the reformed Gang of Four as support, perform a brooding but electrifying show at the Hammersmith Apollo in London |

Pennyblackmusic Regular Contributors

Adrian Janes

Amanda J. Window

Andrew Twambley

Anthony Dhanendran

Benjamin Howarth

Cila Warncke

Daniel Cressey

Darren Aston

Dastardly

Dave Goodwin

Denzil Watson

Dominic B. Simpson

Eoghan Lyng

Fiona Hutchings

Harry Sherriff

Helen Tipping

Jamie Rowland

John Clarkson

Julie Cruickshank

Kimberly Bright

Lisa Torem

Maarten Schiethart