Wilko Johnson - Interview

by John Clarkson

published: 13 / 3 / 2012

intro

John Clarkson speaks to guitarist Wilko Johnson about his years with influential 70's band Dr Feelgood and forthcoming autobiography, 'Looking Back At Me'

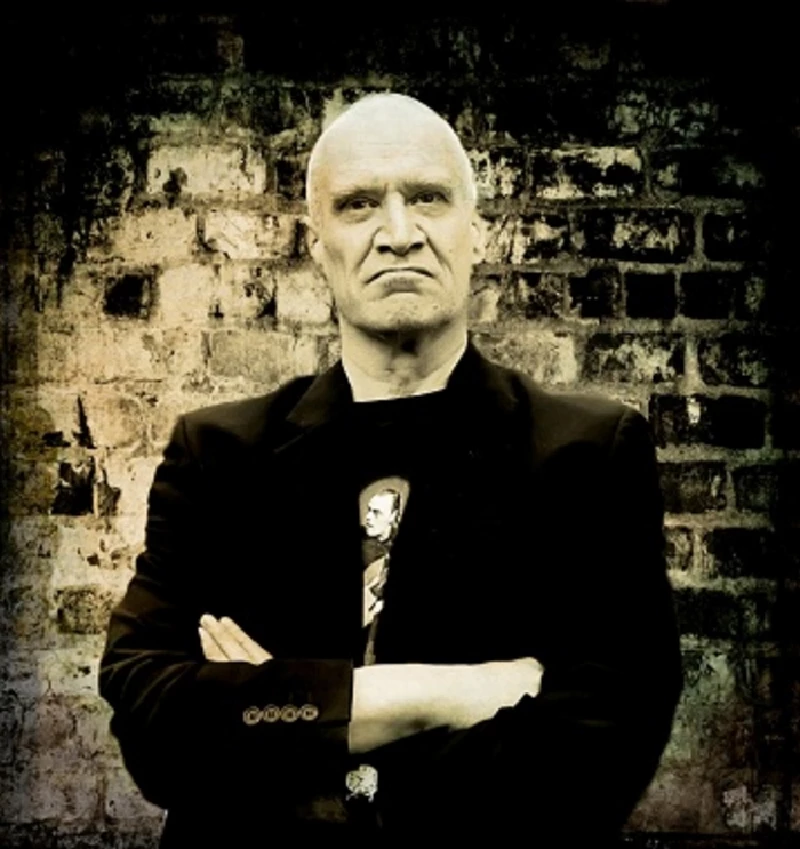

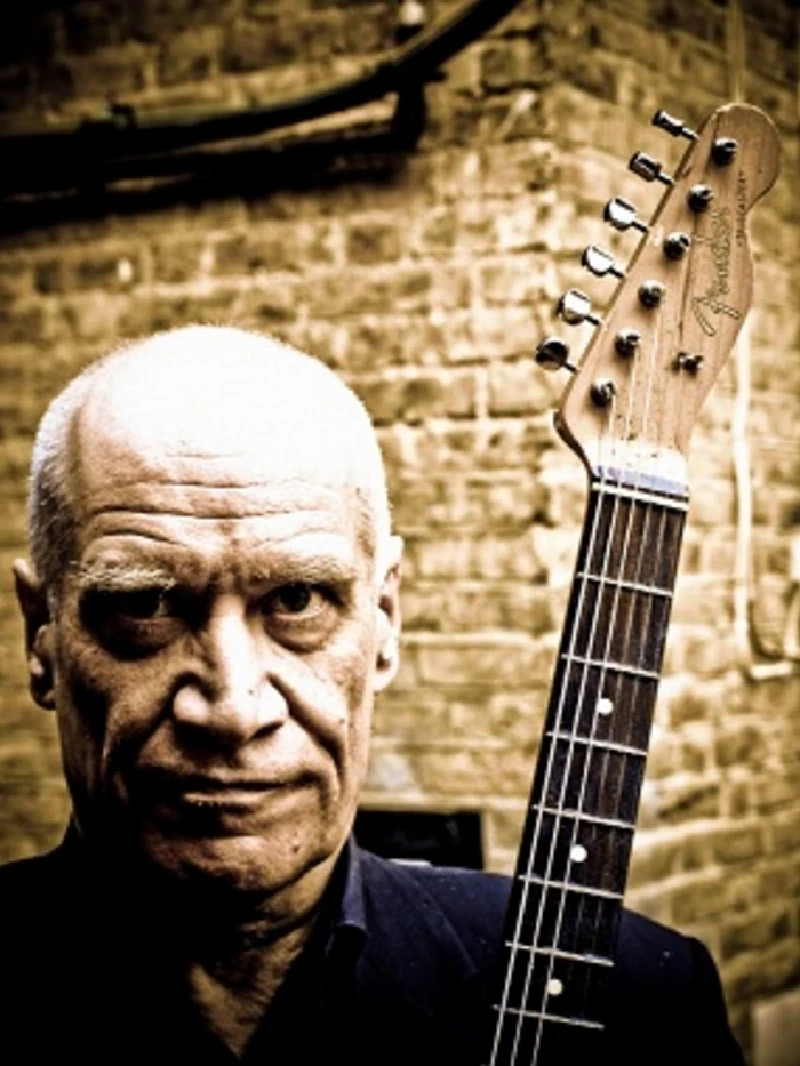

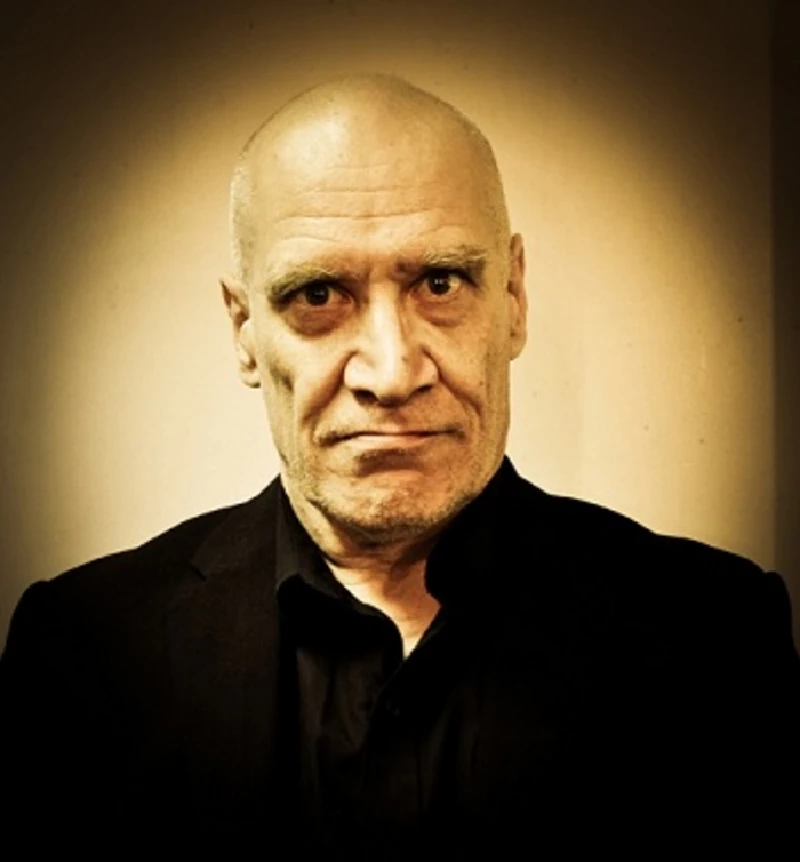

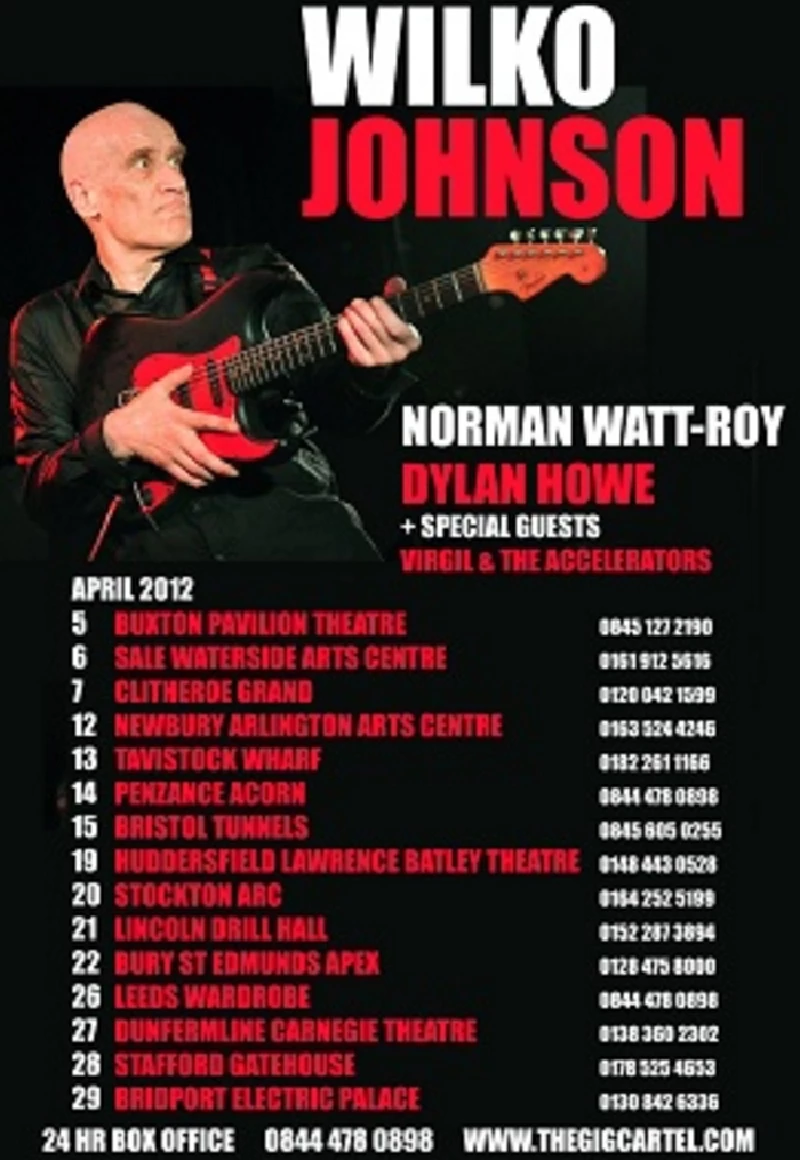

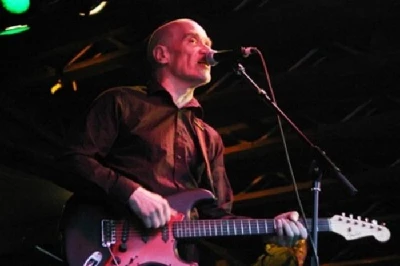

Dr Feelgood’s influence was for thirty years largely forgotten. The group, who formed in the faded Essex holiday resort of Canvey Island in 1971, were the missing link between rhythm and blues and punk. Their early fans included both Joe Strummer and John Lydon, but their original line-up broke up at the height of their success in 1977 when their songwriter and guitarist Wilko Johnson was fired from the band. As punk took off, they found themselves relegated out of music history books. Filmmaker Julien Temple’s 2009 documentary film about Dr Feelgood, ‘Oil City Confidential’, has done much to restore the band’s reputation, and made an unlikely late star out of Johnson. Temple had also made several other music films. He was the director of both the Sex Pistols films, ‘The Great Rock ‘n’ Roll Swindle’ (1979) and ‘The Filth and the Fury’ (2000), and had also made a documentary about Joe Strummer, ‘The Future is Unwritten’ (2007), as well as a comedy fantasy musical, ‘Earth Girls Are Easy’ (1988). ‘Oil City Confidential’, which takes its name from the huge oil refinery towers that dominate the landscape of Canvey Island, through a mixture of new and old interviews, rarely seen live footage and documentary film of the era, captures Dr Feelgood’s rise and then its fall as vocalist Lee Brilleaux and Johnson fell out. As well as Brilleaux, who died of cancer at the age of 41 in 1994, and Johnson, Dr Feelgood also consisted of two other Canvey Island locals, John B. Sparks (bass) and John “The Big Figure” Martin. In the progressive rock era of the mid 1970s, they looked like nobody else, wearing short, brutally cut haircuts and cheap, hand-down suits. Their music was similarly unique, combining Brilleaux’s rasping sneer of a vocal, Johnson’s trademark jerky guitar and the thunderous rhythm section into a huge, but primal and menacing sound. The band’s debut album, ‘Down by the Jetty (1974)’, was recorded abruptly and live in the studio, and its follow-up, ‘Malpractice’ (also 1974), had a similar spiky, malevolent energy. A live album, ‘Stupidity’ (1976), caught the band’s enormous stage presence and spent eight weeks at number one in the UK album chart. By the time the group’s fourth album, ‘Sneakin’ Suspicion’(1977) was released, Johnson, who had been sacked mid-session, was, however, already gone. Brilleaux would carry on with various different line-ups of Dr Feelgood until his death, and, although both Sparks and Martin left the band in 1982, the group, without any of its original members, continues to play and record to this day. After leaving Dr Feelgood, Johnson spent three years fronting the Solid Senders, with whom he released an eponymous album, and then joined Ian Dury and the Blockheads as a guitarist for their third album, ‘Laughter’. Since 1985, he has fronted his own trio, the Wilko Johnson Band, which also consists of the Blockheads rhythm section, bassist Norman Watt-Roy and drummer Dylan Howe. In the time since the release of ‘Oil City Confidential’, the Wilko Johnson Band has been playing to increasingly large audiences. The next few months will be especially busy for Johnson, who is now 64. The Wilko Johnson Band will be playing a fifteen date UK tour in April. Johnson’s autobiography, ‘Looking Back At Me’, written in association with Zoe Howe, is being published to coincide with it. Howe, who is the wife of Dylan Howe, is the author of two previous rock biographies, ‘Typical Girls: The Story of the Slits’(2009), which is about the 70’s female punk band, and ‘How’s Your Dad?: The Sons and Daughters of Rock Royalty’. A Dr Feelgood box set, ‘All Through the City (With Wilko 1974-1977)’, comprising of all four of Johnson’s studio albums with them and a CD of previously unreleased material, is also imminent. Pennyblackmusic spoke to Wilko Johnson about his years in Dr Feelgood, and ‘Looking Back At Me’. PB: You have described your new book, ‘Looking Back At Me’, as being “a fractured autobiography.” What do you mean by that? WJ: It was because this book initially came about and happened without my knowledge really. It was just going to be a piece of merchandise, a book to sell along with the CDs and T-shirts at gigs. Originally it was just going to feature pictures and a little bit of text. Then Zoe Howe started to interview me, and what began with her switching the recorder on and me rabbiting away about playing music, started to expand beyond that, as we began to go into my life story and childhood and thoughts on other things. We also started to find more and more photos and other stuff from throughout the different periods of my life, and so it turned into a sort of autobiography. We didn’t set out to do that. It just came together in bits and pieces, and that is why I called it “fractured” because it is not as if we have a very consistent plot (Laughs). PB: You take a lot of sidesteps as well. There are several pages as well, for example, on your interests in astronomy, Shakespeare, sci-fi and art. WJ: Exactly. I wasn’t the main participant. I was unwittingly providing a lot of the text by just talking and, as I say, it came together in bits and pieces. If you want to hear my wisdom about the twelve bar blues you can, and if you want to hear my wisdom about the galaxies you can as well. Not that I know very much about either (Laughs). PB: The new box set, ‘All Through the City’, is also out in April. How involved were you in compiling it? WJ: Until Julien Temple made ‘Oil City Confidential’, I didn’t really think that much about Dr Feelgood. After I had parted company with them, I never really wanted to dwell on them. I just wanted to leave it as a kind of pleasant memory, and then Julien came along, saying that they were doing this film, and for the first time in years I had to start thinking and talking about those days. That stirred up a lot of things for me that I had left sleeping. With this box set, the interesting thing to me about it was that they wanted to put on it, as well as the four Dr Feelgood albums that I was involved in, this disc full of unreleased stuff. That meant that I had to go rooting around in cupboards and looking for old demo tapes and things like that(Laughs), and it also meant that I spent time up at Abbey Road listening to old studio outtakes and stuff that I had not heard for thirty five years. There are rehearsal tapes on it that come from just before the fourth album, ‘Sneakin’ Suspicion’. Listening to these tapes took me right back because I remember before we went in to do that album I was writing songs and doing demos, and getting quite excited by it, and thinking “Yes! Now I know the way that I want Dr Feelgood to go.” Then we went into the studio, and had a terrific row and the band broke up. ‘Sneakin’ Suspicion’ was in fact produced out of my hands in America. I didn’t really like the way it turned out. It was too produced and smooth-sounding. I wanted the band to go the other way, and some of those demos reminded me of the area which I wanted to get into which was with this really rough and raucous sound, and which was lost on that album. I have never really listened to that fourth album very much because it has got bad memories for me (Laughs). When we found those tracks, I was really impressed by how strong a lot of those songs were. When we go out on tour in April, I am going to be including quite a few of those numbers in the set and playing them for the first time in hundreds of years. PB: Dr Feelgood started out as covers band. How long did it take you before you started putting your own material in your sets? WJ: For two years we played locally in Southend and on Canvey Island and did rhythm and blues covers. Then we started to play in London and very quickly began to make an impact. What we were doing was pretty different to what everyone else was doing at that time, and it became necessary to write songs. We had already got the whole style and sound of the band in place, and so writing was a logical step for me. When I first began to write songs, I would have Lee Brilleaux’s voice and the sound of the band in my mind, and I would specifically write around that framework. PB: Dr Feelgood became the backing band for the German singer and ex-front man with the Tornadoes, Heinz Burt. How long were you involved with him for? There is footage of you in ‘Oil City Confidential’ playing a gig with him at a festival at Wembley. WJ: That happened when we were still playing covers locally. One day Lee was in a music shop and saw this postcard pinned up. It was from Heinz. He was living in Southend and was looking for a backing band. He sold advertising space for ‘The Evening Echo’ or something like that, and on the strength of his brief moment of fame in the 60’s with the Tornadoes he had somehow identified himself with the Teddy Boy/rock ‘n’ roll thing. He would still get regular gigs and would just hire a backing band. We got more money initially backing him in front of a bunch of Teddy Boys than we would on our own. We used to do gigs where we would go on and play the first set ,and then after the interval Lee would probably do one more song and then say, “And now ladies and gentlemen, the dynamic Heinz,” and Heinz, who drunk a lot, would stagger on as pissed as a parrot. We would have our own gigs and then we would have these gigs with him. It just meant more gigs for us really. We didn’t do anything creative musically with Heinz (Laughs). I don’t think he ever quite understood us. It lasted a year or so. We used to do gigs in the RAF bases and at Teddy Boy clubs. It was a bit weird really. The Teddy Boys were a little suspicious of us because we had long hair at the time. Towards the end of our time working with Heinz, Dr Feelgood had evolved into what it became. We had the look and everything, and eventually went our own way. PB: Dr Feelgood often found itself described by journalists in the 1970s as a “pub rock” band. You, however, make a point of saying in ‘Looking Back At Me’ that you never liked the term. What is your objection to it? WJ: My objection to it right from the word go was that for one thing I was very strictly teetotal, and I never went into pubs for any other reason than there were gigs in there (Laughs). I just didn’t like the associations of the word, and also I felt that it was a misleading term. It was something that journalists used a lot. What they were talking about was a bunch of half a dozen venues in London at which serious bands were playing and where you could hear good music. There were all sorts of bands playing these gigs. Every band was different. You had funk bands. You had country bands. You had rock bands, and then they started it calling “pub rock”. Often people think that it is a kind of music. It is not. It is a kind of venue. What is the connection, for example, between Dr Feelgood and Cado Belle? There is no connection really. They are very different kinds of music. PB: Jean-Jacques Burnel from the Stranglers, who was your flatmate at one point in the 1970s, described Dr Feelgood as being “the bridge between the old times and the new times.” Would you prefer Dr Feelgood to be remembered as that or just simply a really good rhythm and blues outfit? WJ: When we succeeded, people, who were coming to see us, realised that unusually for the time we were a very, very simple and straightforward thing. At that time in the early and mid 1970s, there was a lot of very technological stuff going on, gigs with massive light shows and things like that, and then we got up and showed that you could play exciting music without all that. In fact it was probably better to do it absolutely minimally and basically. I think that a lot of what the punk guys who were on our heels took from us was just our simplicity and energy. The whole point of this simplicity and energy was just to give people a good time. If we are to be remembered for anything, I would just like people to remember that they had a good time at our gigs. PB: To pick up on this point further, when you went into the studio to record ‘Down by the Jetty’ and ‘Malpractice’, you insisted on recording it very unusually for that time completely live. You had very little experience of studio work at the time. Did you have any doubts as a result of your lack of studio experience about recording them that way? WJ: No, I never had any doubt about that. When we first started recording, none of us knew anything about how it was done, but I knew that the records that I had grown up with and that I loved had been recorded like that. I knew that when Little Richard had recorded ‘Long Tall Sally’, they got a band in a ballroom and Little Richard out with a microphone, and went mad and got it down in one take. By the mid 70s and by the time we had started recording multi-tracking techniques had come to the fore. It was considered standard for maybe the drummer and the bass player to go in first of all to do their parts, and then the guitar player to go in and do his part, and so on. To me it takes all the feeling out of the music to do it like that, and to this day everything that I have done has just been done in a straightforward way. When we were listening to all this old stuff for the box set, I found a couple of tracks that I can’t remember doing, but it was obvious that we had agreed to try it out the other way of doing it by overdubbing, and when those tracks came on they sounded all very perfect, but totally gutless. It just extracts the feeling for me. PB: You did exactly the same thing with ‘Stupidity’. It really was a live album in contrast to a lot of other bands at the time whose “live” albums relied heavily on overdubs. WJ: Right! This was the thing at that time. If you had got a live album, what you would hear when you played it was maybe the bass drum track that happened on the night, and then the rest of it had all been touched up in the studio. When we did ‘Stupidity’, the record company wanted to do it that way. At one point they told Figure that they wanted to replace every snare beat (Laughs), and I was like, “No. People love what we do when they come and see us live. They will want to buy our live album to have a record of what we do, and that includes bum notes, slip ups and whatever.” If you erase all those ragged edges, then I think the music loses out. I absolutely insisted with that record that they didn’t touch it at all. In fact the only studio work we did on it was because of a fault with the microphone and something missing from the tape, and Lee had to put on a couple of vocal lines. Otherwise we just used what had happened on the night. PB: There were lots of arguments between you and Lee in particular, which lead to you getting kicked out of the group. The book implies that you fell about out every small thing imaginable and yet at the same there was no one big thing which you fell out about. Was that what happened? WJ: Yes. Even when I look back on it now, even in the final argument when everybody ended up at daggers drawn, I don’t know what we were arguing about. In the year leading up to it we had spent a lot of time touring and maybe had spent too much time in each other’s company. I don’t know if it was that or what, but certainly an animosity had developed between me and Lee. We just exploded in the end, which was a terrible shame because when we started out we were such good friends. That is the way I always look back on it and on those days as us as friends. We used to have such laughs. PB: A lot of rock star autobiographies end up trashing the other guys in the band. You, however, don’t say anything unpleasant or nasty about Lee at any point in ‘Looking Back At Myself’. WJ: Well, those are my genuine feelings. Although it was quite heartbreaking when we did break up, Dr Feelgood was one of the most fantastic experiences of my life. I don’t want to look back on that by being bitchy. I want to look back on what happened which was four really good pals from Canvey Island and this mad thing that happened to them. I think all of the good times, and when I think about Lee now I just remember this really great bloke that I was great friends with. What good does it do to look back and trying to blame people? There is no point dwelling on it. If that was one of the great points of my life, I want to remember it as something great and not something horrible and petty. PB: You do your own singing now. When did that start? Was that directly after you left Dr Feelgood? WJ: I never intended to become a musician. Being in a band and a musician was just something that happened. It was never my ambition or a masterplan. I always thought, with regard to Dr Feelgood, that I wouldn’t do anything beyond that but then by time the split-up happened, I was established as a musician, so I thought, “Well, I have just got to carry on,” and so I did as best as I could. I started singing right away, but it took a long time before I found my feet. I thought, “Well, if I am going to carry on, I have just got to get out there and keep doing it. If lose any time, then I will be forgotten about,” and so immediately I seized the moment. I did everything wrong really, and it took me a long time to start getting things right and until after I joined the Blockheads. PB: You have playing with Norman Watt-Roy in the Wilko Johnson Band since 1985 and Dylan Howe since 2008. You have said this is the best ever line up of the group. What do you think Dylan has brought to it? WJ: Dylan is a superb drummer. He takes it so seriously, and is always practising. I have been lucky like that. I started out with a fantastic band which was a big success, and then I was scrabbling around for a while and then gradually things came together, and I joined the Blockheads and met Norman. It is such a great advantage to have Norman on the bass, and then when Dylan came in he was on the same musical level as Norman. Me, I am just a skiffler, but with those two behind me I could just wave my arms in the air and it would still sound great. PB: To move onto present times, you have recently earned your Equity card by playing the role of the executioner Ilyn Payne in the TV series, ‘Game of Thrones’. How have you enjoyed that experience? WJ: It is fantastic. I had never done any acting before and I don’t really know how I got the job. I think that it was in the wake of the ‘Oil City’ film I was asked to audition for it. The character I play has had his tongue cut out. I didn’t have to learn any lines. Basically I think they wanted someone to look ugly and menacing. It has been tremendous fun. PB: You have just completed a second series of ‘Game of Thrones’, haven’t you? WJ: Yeah, I have done, and I don’t think that I am giving away too much to say that I have survived through to the end of it. I think I am going to be there for the third series as well which I will certainly enjoy (laughs). PB: You are also hoping to record an album with the Wilko Johnson Band this year. With everything else that you have got going on at the moment, is it difficult to find time to write new material? WJ: Other than the first Dr Feelgood album, where I had already written a lot of the stuff, I have always written under the pressure of a deadline. It is always difficult to write things. People say to me, “Why don’t you pretend that you have got a deadline?” but I can’t do that. You can’t pretend that you have got a deadline. You have either got a deadline or you haven’t. Also the older you get the more difficult it is to write about the things you see. What are you writing about? You are writing about, “I love you baby but you have done me wrong,” and you’re like, “Come on. I have got my bus pass (Laughs).” PB: Final question. Have you got anything else planned for this year? WJ: The big thing for me at the moment is that also mid-tour in April I am going to meet my grandson for the first time, who was born last October. My son works out in Dubai and he has just presented me with this grandson, so I am looking forward to meeting him That is the other big thing for me at the moment. PB: Thank you. The top photograph that accompanies this article was tkaen by Steve Monti, while the others were taken by Jerry Tremaine. Wilko Johnson embarks on a nationwide UK tour between Thursday April 5th and Sunday April 29th. Box Office: 0844 478 0898, www.thegigcartel.com. Very special guest is Virgil and the Accelerators. Further UK tour date info: www.wilkojohnson.org

Band Links:-

https://www.facebook.com/WilkoJohnsonBand/http://wilkojohnson.com/

https://twitter.com/wilkojohnson

Picture Gallery:-

Visitor Comments:- |

| 554 Posted By: Myshkin, London on 17 Apr 2012 |

|

Ah, the brilliance of Dr Feelgood. That takes me back to my youth. Excellent.

|

interviews |

|

Interview (2010) |

|

| Dr Feelgood guitarist Wilko Johnson talks to John Clarkson about his former band, his new acting career and 'Oil City Confidential', the recent Julien Temple documentary film, about them |

reviews |

|

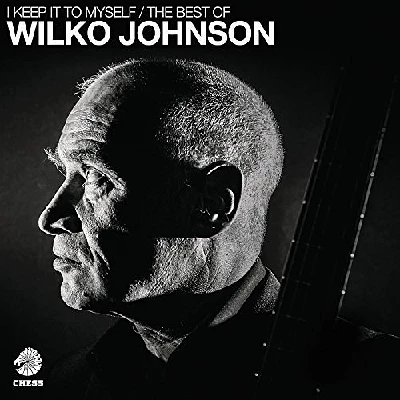

I Keep It to Myself: The Best of Wilko Johnson (2017) |

|

| Fabulous double CD best of compilation from former Dr Feelgood guitarist Wilko Johnson, which consists of songs from his catalogue which he re-recorded between 2008 and 2012 |

most viewed articles

current edition

Carl Ewens - David Bowie 1964 to 1982 On Track: Every Album, Every SongArmory Show - Interview with Richard Jobson

Colin Blunstone - Thalia Hall, Chicago, 16/7/2025

Bathers - Photoscapes 1

Visor Fest - Valencia, Spain, 26/9/2025...27/9/2025

John McKay - Interview

Editorial - July 2025

Robert Forster - Interview

Loft - Interview

Billie Eilish - O2 Arena, London, 10/7/2025

previous editions

Heavenly - P.U.N.K. Girl EPManic Street Preachers - (Gig of a Lifetime) Millennium Stadium, Cardiff, December 1999

Oasis - Oasis, Earl's Court, London, 1995

Beautiful South - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

Trudie Myerscough-Harris - Interview

Pixies - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

Simon Heavisides - Destiny Stopped Screaming: The Life and Times of Adrian Borland

Paul Clerehugh - Interview

Doris Brendel - Interview

Prolapse - Interview

most viewed reviews

current edition

Amy Macdonald - Is This What You've Been Waiting For?Sick Man of Europe - The Sick Man of Europe

Phew, Erika Kobayashi,, Dieter Moebius - Radium Girls

Alice Cooper - The Revenge of Alice Cooper

Davey Woodward - Mumbo in the Jumbo

Lucy Spraggan - Other Sides of the Moon

Blueboy - 2

Cynthia Erivo - I Forgive You

Lapsley - I'm a Hurricane, I'm a Woman In Love

Philip Jeays - Victoria

Pennyblackmusic Regular Contributors

Adrian Janes

Amanda J. Window

Andrew Twambley

Anthony Dhanendran

Benjamin Howarth

Cila Warncke

Daniel Cressey

Darren Aston

Dastardly

Dave Goodwin

Denzil Watson

Dominic B. Simpson

Eoghan Lyng

Fiona Hutchings

Harry Sherriff

Helen Tipping

Jamie Rowland

John Clarkson

Julie Cruickshank

Kimberly Bright

Lisa Torem

Maarten Schiethart