Duane Eddy - Interview

by Lisa Torem

published: 16 / 4 / 2012

intro

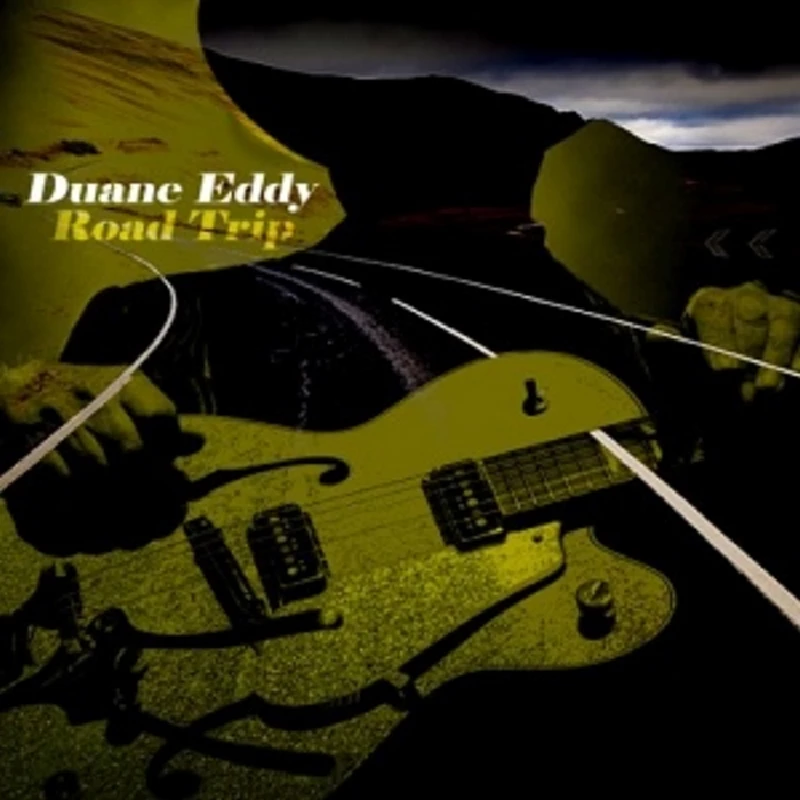

Lisa Torem chats to influential guitarist Duane Eddy about his forthcoming British tour, and 'Road Trip', his first album in twenty four years, which he has recorded with Richard Hawley

Duane Eddy’s cultivated “twang” on the low end of his guitar made his sound instantly recognizable in the late 1950s and early 1960s. The American private-eye series, ‘Peter Gunn’, which featured a theme song composed by Henry Mancini, offered the now Tennessee-based guitarist another integral place in country music history. The song has since been widely covered, but many consider Eddy’s indestructible rendition the quintessential one. After picking up the guitar at five, with no formal instruction, but a bottomless devotion, he garnered a Gretsch by 16, which was modeled after his hero, Chet Atkins. A duo with Jimmy Delbridge ensued, which was soon noticed by local DJ Lee Hazlewood at the station, KCKY, in Phoenix, Arizona (Hazlewood would produce Nancy Sinatra’s ‘These Boots Are Made for Walkin’ and strings of other hits, as well as have his own lengthy solo career). Hazlewood would go on to be a long standing figure in Eddy’s career, but at that time he produced their single, 1955’s ‘Soda Fountain Girl’. Encouraged by the ambitious producer to write a succession of instrumentals, Eddy went home to write ‘Movin’ ‘n’ Groovin’ which led to a contract with Philly-based Jamie Records. The tune, which rose to # 72 in ‘1958, had an opening riff which was even borrowed by the Beach Boys in ‘Surfin’ USA’. ‘Rebel Rouser’, featuring sax player, Gil Bernal, kicked up a sonic storm, too. Eddy’s debut, ‘Have Twang Will Travel’ (1959), remained on the charts for eighty two weeks, after which his unique sound instigated a rash of subsequent albums that reflected popular dance and musical styles. In the 1970s he produced for Phil Everly and Waylon Jennings, but, since popular tastes had changed due to the British Invasion, Eddy did not produce a major hit until the second coming of ‘Peter Gunn’, which, as a result of a surprising collaboration with the synth-dance group, the Art of Noise, in 1986, and despite being pitted against a line-up which included Kim Wilson/Fabulous Thunderbirds, Yes, and the Alan Parsons Project, brought home a Grammy for Best Rock Instrumental Performance in 1986. The following year Capitol Records released ‘Duane Eddy’, an album on which notables like Paul McCartney, Jeff Lynne and Ry Cooder came aboard to offer their production expertise. Early on in the 1990s, he joined Hank Marvin from the Shadows on ‘In the Light’. In the UK Eddy has had the honour of being the sole instrumentalist responsible for Top 10 hits in four different decades and has played the Glastonbury Festival. Eddy’s film work includes ‘Forrest Gump’ (‘Rebel Rouser’), Oliver Stone’s ‘Natural Born Killers’ (‘The Trembler’) and a 1996 collaboration with Hans Zimmer on ‘Broken Arrow’. His prolific output has given way to engaging titles such as ‘The Roaring Twangies’, ‘Duane-A-Go-Go’, ‘Twangsville’ and ‘Twistin’ With Duane Eddy’. It was only a matter of time before the mayor of Nashville designated Duane the “Titan of Twang” in 2000. But by that time he had rightfully earned the 1994 Rock and Roll Hall of Fame Award. After Eddy’s 24-year recording hiatus, he and British producer, singer/songwriter, Richard Hawley took only eleven days to create his diverse album of last year, ‘Road Trip’, which benefits from maestro Shez Sheridan’s crisp bass and sax great Ron Dziubla’s gifted riffs. ‘Kindness Ain’t Made of Sand’ is a one-off instrumental which offers some reflection before ‘Primeval’ swerves with hairpin turns. ‘The Attack of the Duck Billed Platypus’ was penned by Jon Trier, as was ‘Bleaklow Air’, but the rest are conceived by Eddy or co-written with Hawley and Sheridan. ‘ Despite his decades-long success, and indisputable position in pop culture, the multi-faceted artist remains astoundingly humble and appreciative of his mentors, fans and peers. Though he has earned a variety of impressive titles and has written hundreds of now standard songs, he still transmits that unique, magical twang, even over the phone. Now, after returning from the Viva Las Vegas Rockabilly Weekend, Duane Eddy discusses his expansive living legacy, early influences, how he inadvertently stopped George Harrison, literally, in his tracks and his gratitude for the talents and welcoming nature of his ‘Road Trip’ colleagues, before the onset of a long awaited UK tour. PB: Are you living in Nashville now? DE: Just outside in Franklin, Tennessee. PB: You just got back from Las Vegas, right? DE: I did. PB: What were you doing there? DE: Every year they have a big rockabilly festival and car show (Laughs). They have all these 50s cars, the hot rods – it’s kind of like ‘American Graffiti’ comes to life. They park, I don’t know, a thousand cars out there and people go and look at them, and they drive them around, and it brings back a lot of memories to a lot of people. They have some very nice ones there, from the 1950s: ’57 Chevys, ’54 Cadillacs, a’59 Cadillac with those big fins. PB: You have cited Chet Atkins as one of your influences. I read that Chet had to go all across town just to find a place to plug in his guitar, but you and Lee Hazlewood also had to pool your resources. Didn’t you lug a storage tank into the studio once? DE: At the actual local studio, there, in Phoenix, the owner, Floyd Ramsey, and the engineer, Jack Miller, and Lee Hazelwood and I all went down to the Salt River one day to this salvage yard where they had all these 1500, 2000, 2500 gallon water tanks, that were used up and left there, and so we went around and yelled into one to – it was Lee’s idea to find one that echoed inside – we finally found one that echoed -- they all did a little, but one seemed to be a little better than the rest, so Floyd bought it, shipped it up to the studio and they set it up back in the parking lot, wired it up with a speaker at one end and a mic at the other. Our instruments would go through that speaker, swirl around in the tank echo and then be picked up at the other end by the mic and come back in on the tape. This is how we had our echo. PB: Things are easier now. DE: Yes. PB: Getting back to Chet, were you attracted to his actual picking style or his overall performance style? DE: His playing style. I just heard him on record at first and that’s all I knew of him. It was amazing. PB: Do you use the three-finger picking style? DE: I can. I do it. I never would do it in front of him, though. Until one time, toward the end, about three years ago, I had worked up a couple, three or four songs with Doyle Dykes, another thumb picker like Chet, and we worked them up and went to Chet’s Appreciation Society Convention, here in Nashville, where he had an audience of about a thousand people or so. Doyle came up and did a couple of songs and then he called me up and we played our songs. I talked about Chet and how he was a big influence and how I was there because, like the rest of them in that room, I loved Chet Atkins. In between, we were playing our songs and when we were through, Chet called me over because he was sitting over there and he’d never heard me do that. He said, “Duane, you sure play that stuff with a lot of balls” (Laughs). And I thought, well, that’s a pretty good assessment because I’m not clean with it like he was, not smooth. I tend to rock it up a little bit, be a little greasier. I said, “What you mean, Chet, is it takes a lot of balls to play that in front of you.” I should say “guts”, I suppose. I’m giving you accuracy in journalism here. PB: In your early recording career you demonstrated a strong passion for the blues. DE: I met this group called the Sharps. They were with a guy named Thurston Harris. They had a big hit called ‘Little Bitty Pretty One’ in 1958, and I did a show in February in Los Angeles in the State Theater downtown, and I had just my little chart record, ‘Movin’ ‘n’ Groovin’. I just ran up there and played it and ran off. That was the extent of my being rockin’. I didn’t know what to do. I had played country groups all of my life and just was a sideman. So they kind of took me under their wing and said, “You got to move like this, you got to move like that.” I’d see them over there in the wings and they’d be gesturing and everything. The girls would scream and I thought, this is cool. I started getting with it and then they took me down to – they were black guys, the four of them – Watts, that part of town where they had the Five Four Ballroom where they had a big band like Glen Miller, but they weren’t playing that type of music. They were playing blues. They had a girl singer, a guy singer and three or four guitar players and a whole horn section. They wanted me to sit in with them, which I did, and then I started playing blues. I had no choice. They said, “Okay, your time.” The bandleader just pointed at me. I tried to play what I heard them play. I kind of got into it and I got through, and I looked up and he signaled me to go again. I did and I thought, all right, I guess they like what I’m doing. PB: You recorded ‘Three-30-Blues’ which is a very cool tune. DE: Thank you. I did and that was kind of patterned after BB King a little bit. I don’t know. It just kind of influenced it. I did that in Oakland one night and this nicely dressed gentleman came up afterwards and said, “Duane, I love your blues playing” and I said, “Thank you.” “That ‘Three-30-Blues’ – I got to give you a hug.” He came over and just grabbed me and hugged me. And I’m just standing there, my arms against my side. I just sat down my guitar and he said, “It was so good. I got to kiss you on the cheek.” Then he stepped back and said, “I’m sorry. I didn’t introduce myself, did I? I’m BB King.” I said, “Oh, my God. My turn to hug you and kiss you on the cheek.” I thought I finally made it if BB King thinks I’m a good blues player. PB: Jim Horn played sax on ‘Shazam’ and there were other great sax tunes you performed. The sax was such a big part of that early sound. Did you miss those arrangements once peoples’ tastes changed and the sax got pushed to the background? DE: Well, I didn’t miss it, no. I still have to have a sax player to do my old hits when I do live shows, but I do it a little bit because there’s not too many instruments that make a good foil to my guitar sound, yet are powerful enough to stand up to it, if you know what I mean. Piano is nice in some instances and it’s nice to play with a string orchestra or a big band, but I don’t want to play with another guitar player particularly. For a steady diet, if I was recording all the time now, I don’t know what I would use as a foil to my guitar sound, which the sax was perfect for, because it had a big powerful sound and it had offered a relief from the guitar sound. PB: Your tune ‘Tarred and Feathered’ is on a lot of “must have” lists. How did you come up with this arrangement? DE: I haven’t heard that in years. I think I played steel string acoustic guitar on that. It was kind of tongue and cheek, kind of a favorite lick I had and I wrote a song around it. PB: When you write, do you go about it the same way each time? DE: Not every time, but sometimes I just sit back and come up with a mood and a song will come out of that. Other times I’ll have a lick that I’ve worked out or stumbled upon and I’ll extend it or write around it and write a whole song. And sometimes I just get an idea for a melody and it runs through my head. I run over and get my guitar and see if it works, how it works and if it‘s any good, if it’s worth keeping and saving. If it isn’t I forget it, unless it keeps coming back to me and then I know maybe it’s better than I think it is. PB: You even did an album of Dylan songs. He was quite pleased that you, being primarily an instrumentalist, were impressed with his melodies, not only his lyrics. You clearly put a lot of effort into those tunes. DE: I did. But he was right about that -- the tunes are good music. They’re just great songs and, to tell you the truth, a lot of times I couldn’t understand his lyrics, but I don’t have to, do I? I wasn’t singing them, other than I get the idea what the song was about. I’d kind of create the right mood with it, but ‘Blowing in the Wind’ is just a gorgeous song, musically speaking. I didn’t do it, but ‘Lay Lady Lay’ is another one of his that I did do and love. PB: Did you listen to Dylan’s actual vocal phrasing or the instrumental melody? DE: Both. I listen to the vocal for phrasing, but I don’t try to phrase it unless it’s something that needs to be done in a certain way to be true to the song. I listen to the lyric to see what it’s about because if it’s a sad song I’m going to play it that way, but if it’s happy, I’m going to be lighter and more zippy with it (Laughs). Bob’s songs tend to be more philosophical but I try not to be ponderous or anything. PB: You have had quite a history with the ‘Peter Gunn’ song. What prompted the Art of Noise collaboration? DE: A friend of mine was having tea with Derek Green, the head of the China Records Label, and he had this act called the Art of Noise. He told my friend that he had this group which had been doing great in the dance market, but not in the mainstream market. They talked about it but then they talked about other things. And, at one point, my friend said, “Oh, I just talked to my friend, Duane Eddy, the other night.” and Derek snapped his fingers and said, “That’s it. That’s who we can put with The Art of Noise.” My friend was thinking, “I bet Duane would like this. What could they do together?” My friend was thinking frantically because he didn’t want Derek to cool off on the idea. The first thing that came to his mind was, “What about ‘Peter Gunn’?” Derek said, “That’s a great idea. Let me run it past the Art of Noise.” So they cut a track, and then I flew over and put my guitar on it, and changed the ending to some extent to where it would suit me better. I heard a thing and they agreed that that improved it so we changed the last sixteen bars of the song – that was the ending and we put it out. PB: And you won the Best Rock Instrumental Performance Grammy in 1986…. DE: Yeah, we won a Grammy for it. I had a hit with it back in 1959, a more fundamental, basic, funkier version. PB: Which one do you prefer? DE: They’re both different. They’re so different from each other, I listen to the old one and there were good things about that and then I listen to the Art of Noise one and I think it’s very clever, what they did with that. Of course, Anne Dudley (Art of Noise) was a great musician. She played the keyboard and was the arranger. She won an Academy Award for the Full Monty musical. And then JJ Jeczalik was the technician. He did all of the computer stuff. He was the forerunner of sampling. He said to me one day, “You know they call us avant garde, which is true because we ‘avant garde’ the faintest idea of what we’re doing…” That was JJ. He was a character. PB: Your career is really full of surprises. You co wrote a tune for the Oliver Stone film, ‘Natural Born Killers’ with Ravi Shankar. DE: We did that through George Harrison. We went up to his studio. I had this deal with Capitol to do an album and it was right after The Art of Noise thing – I had been in Switzerland doing a rock fest with them, because we had that hit together. And I ran into Jeff Lynne. He said, “I know you’re going to be doing an album after this hit, so when you do it, give me a call. I’ll do whatever you like, produce, write, and play on the album, whatever.” I said, “Okay, Jeff, thanks.” So sure enough I got the deal later that year. I called him up. By this time, it’s probably January or February of the following year. I said, “So you want to do something?” He said, “I can’t. I’m doing something with George Harrison, and I’m producing his new album.” I said, “Okay, fine.” So I hung up and forgot about it. Ten minutes later the phone rings and it’s Jeff. He says, “Duane, I mentioned to George that you called and he wants to put his album on hold and do something with you,” so we flew over and did two or three tracks, which George named, ‘Rockabilly Holiday’. And then he said, “I’ve got this melody that Ravi Shankar sang to me.” He sang it to me and I said, “Oh, okay, you just need to put another part to it,” so I wrote the other part. And George said, “That’s the greatest note I’ve ever heard” because it was one note. (Duane sings the phrase.) It was just an off note, but it worked. Ravi had come up with that and that’s how we wrote a song together. PB: Let’s talk about your experience of working last summer with Richard Hawley on “Road Trip.” What was most memorable? DE: The highlight for me was doing it live in the studio because these guys are all great musicians. I think of them as individual stars in a way. They’re unique and yet they blend so well together as musicians and they all work so well. Most groups fight each other. They’re professional and they come to get the job done. It doesn’t matter which way they do it or who comes up with the idea. We sit down at the studio and, of course, Richard’s the slave driver and the inspiration. He’s the driving force behind the whole thing. The bass player, Colin Elliot, is also the co-producer and the engineer. Nobody does one job. They all do something else. I got such a kick out of it because they take on other jobs and integrate them into what they’re doing. It doesn’t matter what it is. Jon Trier, the keyboard player, who also wrote two of the songs, will be the road manager (Laughs) on the UK tour. He just jumps in there, drives me around, my wife and myself. They don’t think twice about that. People I’ve known in the past have been so insufferable about some things and working with a big star, like Richard is in the UK. They’d be above all of that stuff. But these guys just pitch in. The girl singers work in the office and one of them did the merchandising, and it’s like one big happy family, and they do whatever needs to be done. It’s amazing. So when we got in the studio, and started doing this live. They started writing and coming up with these ideas and it took me back to when I started. Somebody asked me earlier in an interview if it was a bit daunting to go back into the studio after all of this time and I said, “You know it might have been except that it was such a natural thing and doing it that way, live in the studio, that’s the way I started.” So there was nothing daunting about it. It was just totally, completely natural. PB: Which of the tunes best described the landscape you were both familiar with? ‘Desert Song’? ‘Bleaklow Air?’ Which tune conveys the ultimate road trip? DE: That’s hard. That’s like asking me which is my favourite – I don’t have one. ‘Rose of the Valley’ – that’s the thing. Each one has its own thing and they’re all individuals, like the musicians are. Richard is amazing in the studio, and he’s also an amazing guitar player and that made it easy for me because he understood where I was coming from He had all of the qualifications to be my producer. I totally give him all of the credit. I think that’s why the reviews were so great on it because he took my sound and me and put it all together in this great project in which everybody could say, “Hey, I love that or I like that. That’s really good.” I just played and came up with the odd idea or two. But I like ‘Rose of the Valley’ because that’s a fifties thing and, to me it totally represents the fifties without being from the fifties. and the ‘Desert Song’ is probably my favourite, because that’s Richard and I taking a trip through the desert and it’s like the old man and the young man talking, as we go along. Sometimes we talked together in harmony and I couldn’t believe we were doing it. He’d just sit down and start playing and I’d say, “Oh, really?’ Oh, I want to do this. But I don’t want to mess it up. I just want to take it easy and be very sensitive,” and that’s what I did. PB: It sounds like you two have a very comfortable working relationship. DE: It is. PB: Did you enjoy seeing Sheffield through Richard’s eyes? DE: I did and through my own eyes. The countryside around there – I went nuts. We’re driving up this hill, and we’re driving past these trees and these houses and suddenly they all end, and we’re suddenly burst out from under the trees on the road and we’re up on this ridge, and to the left of us and to the right of us are these beautiful fields with stone walls all around them and stone houses in the distance. We come along a corner and further on we come to a canyon, and there’s a pub halfway down there. It’s unreal and it’s the most beautiful country. At the bottom of the canyon, it flattens out and there’s a river and all these little homes and villages. We went to Bakewell and got a tart. Bakewell is known for its tarts and it’s such a charming little village, as many are, but this one looks like it had been built by a film crew (Laughs). It wasn’t… We were just totally impressed and knocked out by all of this beautiful countryside. PB: And Richard had also checked out America to discover its culture, so you had that cultural quest in common. DE: Yeah, but I wished he had called me up. I could have shown him things he would have liked a lot better. PB: Maybe you’ll still get your chance. DE: He’s threatened to come over, but I don’t know. With his own album coming out now, that’s going to keep him busy the rest of this year. PB: So what’s in store for you after all of this excitement? DE: I don’t know. Somebody asked me, “Are you going to do any recording?” and I said, “I don’t know.” I know the album got great reviews, but I don’t know if it sold six figures. You’ve got to sell a bunch before you can go back in and do another one. Richard wanted to do a trilogy, another two albums after this, but whether we’ll do it or not I don’t know. These kids say, “I don’t want to worry about being commercial. I don’t care about selling records; I just want to get my music out there.” I say, “Well, you’re an idiot. That sounds good, and everything, but if you don’t make enough money off of your album, you’re not going to be able to do a second one and your music is not going to be out there.” PB: But you’ll always be playing, Duane, regardless. DE: Yeah, I’ll be playing. I will, and, hopefully, I’ll get to record again. I thought I was through, but Graham Wrench came along, Richard’s manager, and my manager, now, and he said, “You’re not done yet,” and I said, “Au contraire, I think I am (Laughs)” He said, I think you’re not and I said, take your best shot and next thing I know I’m working at the Royal Festival Hall and making a new album. PB: Thank you.

Picture Gallery:-

live reviews |

|

Oran Mor, Glasgow, 16/5/2012 |

|

| Andy Cassidy watches guitar legend Duane Eddy play a triumphant gig at the Oran Mor in Glasgow and twang his thang on his first show there in forty years |

most viewed articles

current edition

Carl Ewens - David Bowie 1964 to 1982 On Track: Every Album, Every SongArmory Show - Interview with Richard Jobson

Colin Blunstone - Thalia Hall, Chicago, 16/7/2025

John McKay - Interview

Visor Fest - Valencia, Spain, 26/9/2025...27/9/2025

Bathers - Photoscapes 1

Billie Eilish - O2 Arena, London, 10/7/2025

Loft - Interview

Robert Forster - Interview

Sir Tim Rice - Interview

previous editions

Heavenly - P.U.N.K. Girl EPManic Street Preachers - (Gig of a Lifetime) Millennium Stadium, Cardiff, December 1999

Beautiful South - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

Oasis - Oasis, Earl's Court, London, 1995

Prolapse - Interview

Peter Perrett - In Dreams Begin Responsibilities Interview Part One

Coldplay - Wembley Arena. London, 16/8/2022

Boomtown Rats - Ten Songs That Made Me Love....

Trudie Myerscough-Harris - Interview

Pixies - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

most viewed reviews

current edition

Sick Man of Europe - The Sick Man of EuropeDavey Woodward - Mumbo in the Jumbo

Amy Macdonald - Is This What You've Been Waiting For?

Lucy Spraggan - Other Sides of the Moon

Phew, Erika Kobayashi,, Dieter Moebius - Radium Girls

Suzanne Vega - Flying With Angels

Bush - I Beat Loneliness

Blueboy - 2

Alice Cooper - The Revenge of Alice Cooper

Cynthia Erivo - I Forgive You

Pennyblackmusic Regular Contributors

Adrian Janes

Amanda J. Window

Andrew Twambley

Anthony Dhanendran

Benjamin Howarth

Cila Warncke

Daniel Cressey

Darren Aston

Dastardly

Dave Goodwin

Denzil Watson

Dominic B. Simpson

Eoghan Lyng

Fiona Hutchings

Harry Sherriff

Helen Tipping

Jamie Rowland

John Clarkson

Julie Cruickshank

Kimberly Bright

Lisa Torem

Maarten Schiethart