Dweezil Zappa - Interview

by Lisa Torem

published: 27 / 10 / 2011

intro

Lisa Torem talks to American guitarist Dweezil Zappa about his Zappa on Zappa project, which will be touring the UK in November and pays tribute to his late father, the legendary Frank Zappa

Frank Zappa was an American composer and singer-songwriter who produced almost all of the sixty plus albums he released with the Mothers of Invention over his thirty year career which flourished in the 1960s. He was also known for expressing publicly his opinions on censorship, freedom of speech and organized religion. Asteroid 3834 Zappafrank, in 1994, and a Californian jellyfish, “phialella zappai, in 1987, were both named in Frank Zappa’s honour, but it was his eldest son, Dweezil, who must have felt his dad, who died in 1993 of prostate cancer, deserved much more of a tribute; a phenomenal musical tribute. Father and son had performed together when Dweezil was twelve at London’s Hammersmith Odeon. Perhaps at that time the spell had been cast. In 2006 in an attempt to draw younger audiences to the music of his father, Dweezil created the Zappa Plays Zappa touring band. Guest artists have included Steve Vai and Terry Bozzio. Originally started in Europe, it soon extended to the US. Dweezil Zappa, who is from Los Angeles, is an American guitarist who has recorded a number of solo albums which include ‘My Mother is a Space Cadet’ (1982) and ‘Go With What You Know’ (2006). His 75-minute piece, ‘What the Hell Was I Thinking?’, which features solos by famous guitarists, and which began in the 1990s, is still garnering interest from legendary guest artists. Dweezil has appeared on recordings with Winger and “Weird Al” Yankovic and has made appearances on film and TV with his sister Moon and his brother Ahmet. Other Zappa related events include ‘Dweezilla’ and multi-day panel discussions, workshops, and orchestral performances of Frank Zappa’s music held in London’s, concert-hall and educational center, called Roundhouse Zappa Fest. Throughout many of these ventures, Dweezil, paying strict attention to detail, set out to reproduce his father’s most popular works, many which have had little literate documentation. His ambitious undertakings, however, have resulted in the creation of the brand new audiences he had hoped for and a Grammy. In addition, Dweezil has reproduced “live” albums that document Frank Zappa’s most popular music, though, in this interview, he explains the pros and cons of continuing this tradition. He will be performing ‘Apostrophe’ across the UK in late November and early December. In this exclusive Pennyblackmusic interview, Dweezil Zappa dispelled some common myths surrounding his famous family. PB: I was wondering why you have chosen to tour the ‘Apostrophe’ album at this time. DZ: Well, ‘Apostrophe’ is one of the most well known records in Frank’s collection of music. It’s also – when you think about introducing Frank’s music to perhaps a new audience - one of the most inviting records because it has so many different textural changes and variety in the music because the core stuff on the record has so many, different styles; rock, jazz, funk and classical. There is also story telling and some really memorable songs; it’s one of his records that just stands the test of time and you always find something new in the details. PB: When you take something like ‘Don’t Eat the Yellow Snow’ which is a very, complex arrangement, what is your break down for working with the other band members? DZ: That song in particular is a suite of songs, so it’s ‘Yellow Snow’ into ‘Nanook Rubs It’ into ‘St. Alfonzo’s Pancake Breakfast’ and on the record there it goes to the next song, which is ‘Father O’Blivion.’ We’ve been playing that song or that series of songs for a while, and on this last tour we added in a piece called ‘Rollo’ which is not as well-known unless you’re one of the super fans (Laughs). What that is is - the piece from the end of ‘St. Alfonzo’s’ is a really, fast, crazy unison line that actually comes from that piece of music, ‘Rollo.’ – a classical piece which is more fully arranged and has all of this counterpoint stuff. We added this on to the arrangement on this last tour, but we probably won’t be playing it attached to ‘St. Alfonzo’s’ the way we are now. But the question you asked is how we tackle something like that which has all of the different variables that come with Frank’s music in general - the first thing we obviously do is look at the album and the version that we’re trying to go with. With ‘Apostrophe’ playing it like the record, we try to recreate all of the textures and we try to replay (Laughs) all of the right notes. That is the ultimate challenge because sometimes we have to transcribe the stuff ourselves because it’s not necessarily already written out and on paper. Sometimes it is and sometimes it isn’t, but even then, whatever is written on paper if it’s not written in Frank’s own handwriting, you still have to weigh it against the recording. There are different notes written than what you hear on the recording. You need to refer to the recording because that is obviously the way Frank put it out and wanted it to be heard. We assume those are the most correct notes, even though there might be something wrong on the page. PB: Do you act as an actual physical conductor then when you get to that point? DZ: No, we learn the piece of music and kind of lock in the tempo in our minds, and if there is anything that actually requires a visual cue, we just turn around and look at the drummer. I didn’t want to do anything that put me in the position of being a conductor, mainly, because one of the things that I wanted to avoid from the beginning, on this project, was anybody getting the impression that I was just trying to turn into my dad. I didn’t want to try to fulfill a role that made it look like I was doing an impression of him or something. The way that I chose to tackle the music was to let the music speak for itself and do very little in terms of the way the music is presented – what I mean by that is – we don’t have lasers and smoke and dancers and light shows and we’re not running around the stage – we’re just playing the music (Laughs) and that was what I thought was the most appropriate approach. PB: So many times an artist, who has a famous parent, tries so hard to distance himself from the person, live performance or discography of that parent; perhaps in an effort to forge a distinct identity. You are unique in that way, but was that always the case? DZ: The thing about Frank’s music is, and the reason that I chose to do this project. was that so many people that are under the age of thirty are unfamiliar with his music, and his contributions to music are so vast that I just thought that it was a shame for it to go unrecognized into the future. I thought if there was a chance to open up a portal into this music for younger generations, experience the music for themselves, that they would find that it is very contemporary music, not nostalgia music. This is music that was ahead of its time and will always stand out, so I thought there’s really no better custodian for it or somebody who is going to care about it as much in all of the different levels of detail – so why not be part of the effort to bring it to a new generation? I just didn’t want to see it fade away in my lifetime which is what it seemed like was possible. PB: ‘Cosmik Debris’ seems very bluesy and like it would leave a lot of room for improvisation. Is that what usually happens with this tune live? DZ: We play it in the standard arrangement that you hear on the record and on other tours we have expanded the solo section and turned it into a band solo song; so you would hear a marimba solo or a sax solo or you would hear a couple of guitar solos or a keyboard solo. You get a texture of the band and how the band interprets the blues. We have done that, but on this particular tour we stick to the length and arrangement that is on the record. Although I don’t play the guitar solo, note for note, I do play very much in the style in which Frank played and with a similar sound that he played. It evokes the feeling of the record. PB: Wasn’t that originally recorded with Jack Bruce? DZ: Yeah, he played on it. PB: So, are you also trying to recreate that sound? DZ: When Pete Griffin, the bass player in the band, plays the solo he does create a fuzz tone kind of sound and play some of the phrases from that solo, but he doesn’t do the solo note for note either. That’s a moment for him to be able to improvise, but I do recreate the textures of Frank’s guitar sound on that because he does have a very interesting lead guitar sound on that one which I do play note for note on that solo. PB: So what were you looking for with this current band? You have Ben Thomas, who one of your fans described as “having a glass-shattering voice.” How does Ben do interpreting Frank’s music and how does he compare to your prior vocalists? DZ: I haven’t heard that description of him, before as “glass-shattering.” He doesn’t really have a super high register. It is more in a tenor-baritone area, but Ben came into the band in a challenging time because we were set to do a tour of Europe, and we had a singer in mind that was supposedly working on all of this material and then was going to come in and audition, but we had about two or three weeks to really ratchet it up and get it all going. Anyway this guy completely failed the audition. He just didn’t put the time in advance. It turned out that he really didn’t have the requisite skills, so that put us in this weird position – we had three weeks if we had the guy that was really going to do the rehearsals and pull it all together, but that time started dwindling down, so we were almost a week, maybe even six days from when we were going to get on an airplane and do this tour of Europe which was a pretty extensive tour, and we still didn’t have a singer. We were auditioning and auditioning and we found Ben, and really what made it possible to join the band was he was able to sing the song ‘Inca Road’ which has very, difficult melodies, but it also has really tricky rhythms. Ben has a very good ability to learn that stuff the way a musician does as opposed to just a singer, because he also plays trumpet and percussion, so that was an asset to him – being able to understand walking in and getting the rhythms right; he also had a really good work ethic so when we found out he could do that one song we said, “Okay, how many songs do you think you can learn by tomorrow?” He ended up learning about four or five songs, came in and really did the songs well, so we figured if he can learn four or five songs in a day, let’s take him out there. He’s got time to learn more of this stuff on the road – we basically need him to have about ten songs that we can work throughout the show, and he rose to the challenge to do it and he’s been in the band ever since. PB: Will you be using audiovisuals of Frank with this tour? DZ: We’ve done it before with this presentation of ‘Apostrophe’. I haven’t decided yet whether to continue to do that for this version. It really just comes down to the way the venues are set up, whether or not we can get the equipment set up properly and the logistics and the cost of bringing the gear. If it works in some places and it doesn’t work in others, then you’re kind of wasting money. I just don’t have all of the details yet, but when we do it is an effective part of the show and people do like to see Frank performing with the band. PB: And how does it feel for you personally? DZ: It’s obviously bittersweet. The effect of it really is that when Frank is up there, he is in his prime. He’s doing what he does best. For a lot of people it feels like – there he is, he’s back – and it’s really pretty cool to see how it all works. He’s singing and he’s playing guitar so I can turn around and there’s one part in ‘Cosmik Debris’ when we do the version with the video where we have a little bit of a guitar trade-off. There are cool elements to it. I do like using it, but I don’t want to overuse it. The other thing is that we don’t have that many variations on the things that we use, so every time we do that performance with that stuff it is the same video. There are just not a bunch of options that we have for that stuff. PB: Dweezil, you have the famous Hendrix-Zappa Strat in your possession. Do you feel like you’re in another lifetime when you pick up an instrument like that? DZ: That guitar, itself, any guitar player that I have presented it to and let them play it – they all have a similar feeling of getting goose bumps just because Jimi Hendrix is legendary; my dad, also in his own way, is legendary as a guitar player, but an instrument that was played by both of them is unique. There’s no way to verify any other situation that is similar. For example, we don’t know if Beethoven and Mozart played the same piano. It’s possible that they did, but who knows? But, in this case, this is a pretty, rare occurrence where two legendary musicians shared the same instrument and created amazing things with it so when I play it I’m certainly well aware of the history. It’s a fun guitar to play. I recently refurbished the guitar to put it back to the way that it looked when people first saw Frank with it. He was on the cover of ‘Guitar Player Magazine’ in 1977 holding that guitar, and over the years he changed the way that it looked by putting different pick guards and necks on it. I restored it to the way it looked on the magazine cover, but I didn’t have the original parts because they had disappeared over the years, so I had to painstakingly search out replacements that would fit the bill. PB: Dweezil, you had started a recording project chronicling guitarists: ‘What the Hell Was I Thinking?’ Are you still working on that? DZ: It’s not complete. The interesting thing about it is that, with all of the things that I’ve learned doing with ‘Zappa plays Zappa’ it’s got me inspired to make some alterations to that project and update some of the things that are in it just for my own playing standpoint and compositional standpoint because really what it is – I describe it as an audio-movie. I have a lot more ideas to add to it. I’m not in a huge hurry to finish it. It will be a pretty unique thing when it’s done because it has over 45 different players on it, ranging from Eddie Van Halen, Brian May, from Queen, Malcolm Young from AC/DC, Steve Morse, Brian Setzer – there are a bunch of different players in there. I’m leaving out dozens of really, well-known guys, from Joe Walsh to Yngwie Malmsteen, but there are guys that I still want to get on there and record with; Jeff Beck and Jimmy Page, Alan Holdsworth; different styles of players, but, in the end, I’m hoping to actually mix the whole thing in surround sound and really just make it into a wild, musical ride (Laughs). PB: Are you asking the artists to choose their own solos? DZ: What happens is I write a piece of music that is in a vein that is familiar to them, or something completely outside what they would normally do and so there is that variance. It’s been really interesting because the end result – you hear people out of context and it’s really interesting to see how their playing adapts. One thing I did with Eddie Van Halen was that I wanted him to play a solo that was comprised of many of his most well-known guitar licks – like a greatest hits guitar solo - so I sat there and I said, “ I want you to play these licks, okay?” I had already learned some of them already, so that was the way that I was able to communicate which guitar licks I wanted to include in the solo. But, it was funny because some of them were things that he hadn’t played in a long time and he would say, “How did it go? You play it – you sound like me anyway!” PB: Do you see going back to “The Return of the Son of” material? DZ: More live albums? PB: Yeah. DZ: We’re probably going to do something like that, but originally I had no intention of making any live albums with this band because the point of doing this whole thing was to introduce people to Frank’s music and discover his recordings. But, what we found in the process was that people that really enjoyed this band liked this band and they became interested in seeing what this band would do even outside of Frank Zappa music, and we’re being asked quite frequently “When are you guys going to make a record of your own music?” That’s a possibility as well, but as far as ‘Zappa plays Zappa’ albums, the reason to do it at all became apparent, because what happens with Frank’s music anyway is that on every tour he would always do a new version of songs. So he was never really doing what it sounded like on the record, so the thing that is cool about the versions that we’re doing is that the fans, from what I gather from talking to them, what they really appreciate about it is a chance for the music to be alive again; in the sense that when Frank was touring they’d get to hear a song but they knew that, because of the way that the songs are constructed, there’s always a chance for some improvisation. It’s extending the reach and the life of the song by allowing these new, improvisational sections to come into play, because we play very, very close to the original versions or at least the versions that we are choosing to play. The point is that the songs are alive and breathing again with new elements; so the people who have exhausted their catalogue, of listening to all the same versions of all the same songs that they know and love get a chance to hear some new ones. That’s why they like this option as a live album cut. It keeps close to the original fundamentals – so, it’s the closest they’re going to get as a real thing. PB Frank was very political; he appeared at a Senate hearing to respond to the Parent’s Music Research Center quest to rate recorded music. He also considered running for president and was asked to be a cultural consultant for Vaclav Havel. Has Frank influenced you in this way? Do you feel a need to express yourself politically, especially in issues that affect musicians? DZ: I haven’t decided to do anything in a public forum. Obviously, I have a lot of respect for what my dad did, and we should all be thanking him for a lot of the things he stood up for; in terms of our freedom of speech and all of that stuff. For me, the climate of what everything is – there is so much apathy out there anyway when it comes to the American public and politics and everything. I am just not that motivated by all that - my life is challenging enough, time wise, and I’d rather spend time with my children than going out and speaking up about anything political. PB: Didn’t you have an unorthodox type of childhood? You were pulled out of school early, weren’t you? DZ: I wasn’t pulled out of school. I was going to a school that – it was a public school at the last part of my high school – and there was a kid in my homeroom class who was doing cocaine and I went to the principal and said, “Hey, this kid is doing cocaine.” In any case, I got some types of threatening calls and things because I had done that. The thing was that that shouldn’t be happening and the kid needed some guidance or help to get out of that situation. At that point, when we were receiving that kind of information, it was better for me not to be going to that particular school at that time so I ended up taking the high school proficiency test and got out, but I was pretty, nearly geared towards having a musical career. So, after getting out of high school by taking the test, I just went straight to work. PB: Did you feel you had an unusual upbringing? DZ: The thing is you could ask anybody about his or her upbringing and they’ll say that that was just what was normal for me; if that’s all you know. It definitely was a lot different from a lot of other parents’ perspectives, but I’m pleased with my experience growing up (Laughs). PB: Are people surprised when they find out that Frank Zappa did not do drugs? DZ: Yeah, because they think he’s the crazy guy who named his kids all of these crazy things; even more surprising is the fact that none of his kids ended up getting involved in drugs in any way. You look at all of these celebrity families; ‘Celebrity Rehab’, whatever. It is possible to raise kids that have no interest in any of that kind of stuff. I’ve never taken a drug in my life and I never had any interest in it. I’ve never been drunk. I’ve never smoked a cigarette. All of that stuff was around me all of the time, by virtue of the fact that I could see it in Frank’s audiences. I remember being around eleven and people were acting all crazy at one of his shows and saying, “What’s wrong with those people?” Frank said, “Those people are either drunk or stoned and they think that gives them an excuse to be an asshole.” So knowing that he had this type of disdain for this behaviour, it was really easy for me to see the logic in not doing any of that stuff and also just seeing people being idiots. So I didn’t have any desire to do any of that and the whole creative side of things – it’s much more impressive to use your brain for the natural creativity as opposed to being under the spell of a chemical, to pretend to be more creative. Having said that you’ve got to take into consideration the majority of the music in the 1960s and 1970s was written by people that were fucked up (Laughs). So there are a lot of people thinking, “Oh, that’s the only way to be creative.” But, Frank didn’t do any of that. He had the reputation of being the crazy musician - that was all just coming out of his brain (Laughs) PB: But, he wasn’t heavy-handed with you guys. Some parents are so strict that their kids sneak out of the house. It seems like Frank was more experiential. DZ: What it really comes down to in terms of the relationship that I had – and the understanding that I had with that stuff – if you have respect for your parents and you appreciate their point of-view, and they’re telling you the truth about stuff – we were prepared for reality. A lot of kids are not prepared for reality. They’re not prepared for what the real world has to offer you and how challenging it really is once you get out there. There’s so much sheltering of so many things in modern society (Laughs). So, if a kid doesn’t respect his parent, anyway, they’re inclined to do these experimentations and not really care what their parents have to say about it. Well, good luck, but it’s not going to work out too well. PB: How do you account for the work ethic you share with Frank of seeing things through to the end? Not everybody has that drive or desire. DZ: I think it really is just lead by example. I could see he worked and I could see that he enjoyed his work, and the things that I like about what I get to do is that they are satisfying on many different levels. I try all the time to keep learning new skills and things about things that I already know because there is always a chance that you can surprise yourself and take it to the next level. What Frank did in his music was constantly try different things so that was an easy lesson for me to learn and it’s something that I also enjoy because gathering knowledge and putting it to good use is a satisfying process. I could see how that worked, growing up, and I put it to use in my own way, in my own life. Having an idea that you have just in your head that then becomes something for the rest of the world to share; it’s a very interesting concept. Music is created that way. It is something that is heard singularly in your head, and then you take it out of your head by various, transformative processes where you’re putting in some type of vehicle for somebody to take home and listen themselves. But, you’re translating your idea through teaching it to other people, recording it and all of these things. Nobody would have known anything about it had you not gotten it out of your head; it’s this bizarre, creative process, so it keeps it interesting. When you consider all of the things that Frank unleashed and got out of his brain on to paper or on to records, it’s astonishing – the output and the variety within it. We’re still dealing in western music with twelve tones, and the way that he was able to constantly rearrange those same, twelve tones that everybody else was using that made it seem like he had a very different toolbox than anybody else. It’s very remarkable. PB: Did you listen to classical music when you were a kid? DZ: I did listen to it with my dad, and I did listen on my own, but there were certain composers that I was interested in. I tended to be interested mostly in things that were written for strings. I liked the sound of cellos and violas and stuff like that. I could appreciate other things, too, like the bassoon and clarinet because I liked the lower registers of those instruments. But I liked Dmitri Shostakovich. PB: Do you have an attraction to atonal music? DZ: Some of that stuff has some big dissonance in it, but it is also descriptive in the sense that you get the idea (Laughs) of the environment that this guy was living in and it didn’t seem like it was the happiest place, but the music was intense. One of the things that I’m interested in, these days, especially when it comes to improvisation – for me, all these years of playing and the most recent years of touring with this music - my playing has changed so drastically in order to play Frank’s music, but now I have sort of a facility to bring in different textures. So this idea of steering away from consonance and adding in these darker colours of things that may sound more random or atonal, that becomes much more appealing to me because I have the facility to mess around with it while I’m playing, so that’s kind of a new direction. PB: Which album, for someone who hasn’t heard Frank, would be a great introduction? DZ: ‘Apostrophe’ is usually high on my list. If it’s the first thing that they’re ever going to hear, I usually say ‘Apostrophe’ or ‘Overnight Sensation’. Then, I have them go backwards after that to ‘Freak Out’ and ‘We’re Only In It For the Money’ because I like people to have a window in to something that I think is a little bit more digestible – ‘Apostrophe’ and ‘Overnight Sensation’ –- and then just go back ten years and see what the difference is from where he started and see how crazy it was right from the very beginning. So, then they can usually fill in the gap and find their way through the catalogue. PB: Thank you.

Band Links:-

https://www.dweezilzappa.com/https://www.facebook.com/DweezilZappaOfficial/

https://twitter.com/DweezilZappa

interviews |

|

Interview (2017) |

|

| American guitarist/composer/actor Dweezil Zappa chats to Lisa Torem about his forthcoming UK tour and his father Frank's legacy |

live reviews |

|

City Winery, Chicago, 7/7/2017 |

|

| American guitarist and educator Dweezil Zappa entertains fans at City Winery Chicago with delightful stories about his father, formative career and more, using his red SG for effect. |

| Chicago Music Exchange, Chicago, 10/10/2013 |

| Royal Concert Hall, Nottingham, 12/11/2012 |

soundcloud

reviews |

|

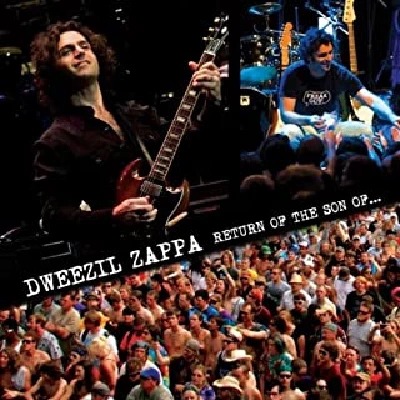

Return of the Son of... (2010) |

|

| Exhilirating and provocative double CD collection of covers from Dweezil Zappa of his late father Frank's work |

most viewed articles

current edition

Carl Ewens - David Bowie 1964 to 1982 On Track: Every Album, Every SongArmory Show - Interview with Richard Jobson

John McKay - Interview

Colin Blunstone - Thalia Hall, Chicago, 16/7/2025

Billie Eilish - O2 Arena, London, 10/7/2025

Bathers - Photoscapes 1

Loft - Interview

Visor Fest - Valencia, Spain, 26/9/2025...27/9/2025

Sir Tim Rice - Interview

Robert Forster - Interview

previous editions

Manic Street Preachers - (Gig of a Lifetime) Millennium Stadium, Cardiff, December 1999Heavenly - P.U.N.K. Girl EP

Beautiful South - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

Oasis - Oasis, Earl's Court, London, 1995

Peter Perrett - In Dreams Begin Responsibilities Interview Part One

Boomtown Rats - Ten Songs That Made Me Love....

Coldplay - Wembley Arena. London, 16/8/2022

Prolapse - Interview

Pixies - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

Trudie Myerscough-Harris - Interview

most viewed reviews

current edition

Davey Woodward - Mumbo in the JumboSick Man of Europe - The Sick Man of Europe

Lucy Spraggan - Other Sides of the Moon

Amy Macdonald - Is This What You've Been Waiting For?

Phew, Erika Kobayashi,, Dieter Moebius - Radium Girls

Suzanne Vega - Flying With Angels

Bush - I Beat Loneliness

Alice Cooper - The Revenge of Alice Cooper

Cynthia Erivo - I Forgive You

Blueboy - 2

Pennyblackmusic Regular Contributors

Adrian Janes

Amanda J. Window

Andrew Twambley

Anthony Dhanendran

Benjamin Howarth

Cila Warncke

Daniel Cressey

Darren Aston

Dastardly

Dave Goodwin

Denzil Watson

Dominic B. Simpson

Eoghan Lyng

Fiona Hutchings

Harry Sherriff

Helen Tipping

Jamie Rowland

John Clarkson

Julie Cruickshank

Kimberly Bright

Lisa Torem

Maarten Schiethart