Swans - Interview

by Jamie Rowland

published: 9 / 10 / 2010

intro

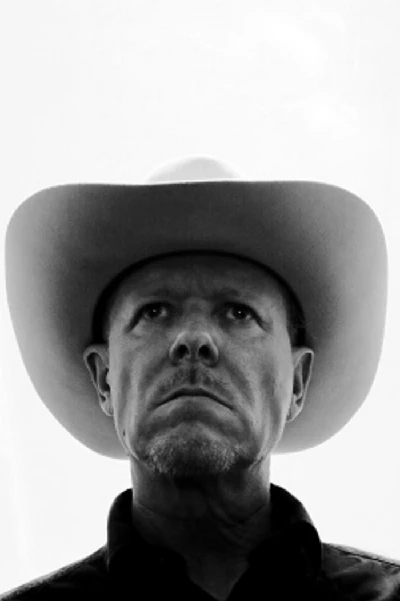

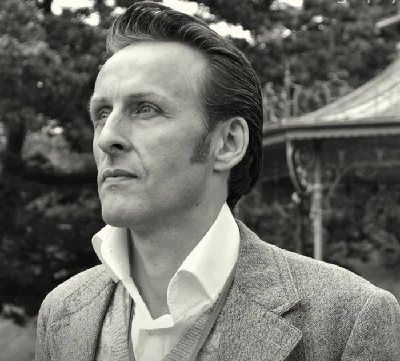

Jamie Rowland talks to Michael Gira about his recent decision to reform his influential post-punk band Swans, the state of the music industry and his early years as a musician in New York

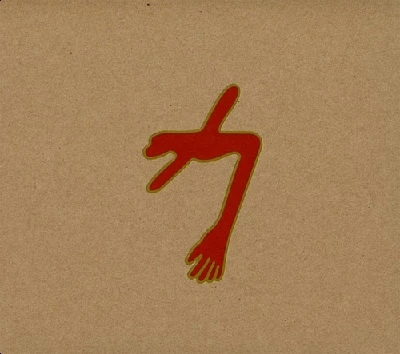

In 1997, Michael Gira disbanded his group Swans after fifteen years and eleven albums. Now after years away focusing on his label, Young God Records, and creating music through his Angels of Light outfit, Gira has brought Swans back from the dead. Having released the brilliant new album, 'My Father Will Guide Me Up a Rope to the Sky', and touring the UK and Europe at the end of October, the songwriter/producer/visionary that is Michael Gira took time out of his busy schedule to talk to Pennyblackmusic about bringing the band back together, the state of the music industry, and starting out in 1980s New York City. PB: It’s been thirteen years since you dissolved Swans. What made you decide that now was the right time for the band to return? MG: Well it wasn’t really a decision based on timing; I had material that I wanted to record, and I was thinking about as Angels of Light and it just didn’t really excite me. And I’d been wanting to make more kind of all-enveloping, overwhelming sounds again and I had been mulling over the idea of restarting Swans, with both negative and positive emotions associated with that decision. Finally, I just said, “Fuck it, it’s my band, I don’t care what anybody thinks, I’m going to start it.” So now I’m pursuing that. This album is I guess, in a way, a hybrid between both projects – Angels of Light and Swans – in that these songs were written on acoustic guitar initially, with the idea that I would record them acoustically and then over-dub on them, which is a technique I used on Angels of Light pretty much all the time. Whereas with Swans, I would write a song on acoustic guitar, electric guitar, bass or whatever, and then I would take it into the band and start expanding it – so this has both those approaches on it. Whereas, the next Swans album, which I’m already starting to think about, I’ll write the basic music ideas and words and then start working with the band as Swans. So it’ll be much more focused on long instrumental passages, things like that. PB: Well that mixture certainly comes across on 'My Father Will Guide Me Up a Rope to the Sky'; the songs sound very much like a mixture of the two bands’ styles. MG: Well Swans changed so much over the years – and it’s really just the work that I do and the people I involve; you put a name on it, it’s kind of arbitrary –it just wouldn’t have felt right to call this album Angels of Light. I was toying for a while with calling it 'Swans/Angels of Light', but that’s so vague, you know? PB: There’s certainly a return to the intensity Swans are known for MG: Oh yeah. It’s more open, and it’s loud guitars playing, which have a lot of overtones. I used a lot of guitars in Angels too, but not to such an extent. I don’t know what to say except that somewhere inside me I know if something’s Swans or Angels of Light respectively. And this is definitely Swans. PB: Swans were formed in the 1980s, which many see as a very dark decade, and it could be said that the band too reflected that time in their sound. Do you think your decision to restart the project was in any way influenced by what seems to be an increasingly gloomy world, post-2000? MG: Well I think we’re certainly entering what looks to be a very dark, if not a lightless decade. Things are looking pretty bleak, aren’t they? But no, it’s not a comment on the zeitgeist or a need to associate myself or work against or for that. But I guess there’s a notion in Swans which is sort of reaching for obliteration, which maybe kind of fits with the time right now. PB: Earlier this year, you also released a solo album of sorts, 'I am Not Insane'. MG: Yeah, well it wasn’t really a solo album; it wasn’t meant for the general consumption of the public. It was the songs that I had written for an album, and I recorded them here at my desk with a DAT recorder, and packaged them and made a thousand wood block prints with drawings on them in four colours of ink, and took hundreds and hundreds of hours on it. Anyway, I did this to raise the money for the Swans record. So I did this CD/DVD package called 'I am Not Insane', and assembled it, and it was really a nightmare because I expected to sell a couple of hundred in the first month or something, but one thousand sold out in two and a half weeks. So it was a blessing and a nightmare; I’d only made a couple of hundred in advance, and right at the time when I released it I was going into the studio with Swans so I was like “Oh my god, I’ve got twelve hours today in the studio, and then I have to try to come home and assemble these things.” It just turned into this whole three-month ordeal of trying to ship them out to people who ordered them. But, yeah, this recording was funded largely by fans. PB: It must be very gratifying to have all those people willing to help you get this album made and released. MG: It is gratifying, yeah. It’s kind of ironic that, due to the climate in the music business – if one can use such a word without throwing up! – that I have to work eight times as hard to make one quarter the amount of money back (laughs). So I had to do all this in order to make the money, to then pay to record an album which I’ll then release. And then – certainly not my fans – but a lot of people are going to download it and not buy it, you know? So it’s bittersweet I guess. There’s all these gymnastics you have to go through to induce people to actually compensate you for the work you do PB: Which in a way is shooting themselves in the foot, because if they don’t buy these records, certainly on independent labels, they won’t have the money to make any more. MG: Well, I can tell you right now that Young God Records is disappearing due to this problem. I’ll keep releasing music by people that are on the label already, but I can’t work as hard as I do and invest the kind of money I do in artists whose music I love – work that hard, and then just have it not sell because people steal it. I can’t endure it anymore. There’s no way I could survive; I have a family, I have to live, I’ve got a kid. So it’s not tenable. But that’s a direct result of illegal file sharing, basically. I know because I – I don’t want to use the word ‘discover’, it sounds like I’m some explorer or something – but I bring people's music to the world, people who previously had not been known, and I work really hard over a period of say, eighteen months to get them started – help arrange their songs, produce their music – hundreds of hours invested with love for the music. And then put it out there and it sells, you know, a couple of thousand or something, as opposed to in the old days, where it would be a lot more than that, and meanwhile their live attendances grow exponentially. But no one buys the fucking record! (laughs) So it’s kind of a stupid position to be in. So I just accepted that that’s the way it is. Somebody’s going to have to figure it out, but I’m not able to. PB: It’s a very complex issue for the industry as a whole I suppose; it seems that if you fight it too hard and put lots of restrictions on people, they will try to get round those restrictions, maybe even just through some sort of resentment... MG: Yeah, but they just have to be aware, you know? Just because they can get it as an MP3, that it’s not a physical thing they can look at. They don’t understand that within those sound waves there’s hundreds of hours of work, a whole life experience and the discipline that went into being able to do it in the first place, as well as payment for studios, musicians – all this stuff is embedded, so to speak, in that three minute song, you know? But they probably never had to work to make something themselves, and invest in something themselves so they just think “Oh, I’ll just have that” PB: As you say, a lot of that de-valuing of music probably comes from the fact that there is no record or CD you can hold in your hand, the music as a product is something more abstract than it used to be. MG: Right, and then people complain about how much CDs cost – or how much they were, in the past – which may be fair, but it wasn’t just the cost of manufacturing the CD, it was all the other integral cost that I mention that went into it. So anyway, I’m not trying to present the case for unbridled capitalism, but it just doesn’t seem fair to me. One wouldn’t expect a carpenter to work for nothing, so why should a musician? PB: The artwork that you have for the records you release, both on your own projects and those bands signed to Young God Records, is always very striking. I know you work with various different artists to produce that work, but I was wondering if you have any particular process for working with those artists to come up with works for particular albums? MG: Usually it’s a pre-existing piece of art that I come across somehow, serendipitously, and it just fits. That’s usually the case. I have an eye for that, and also there’s a particular design scheme for the label that makes things striking. The cover for 'My Father...', that’s by Beatrice Pediconi, an Italian artist who is really good. I had been mulling about for a record image, and I was reading this magazine and I saw one of her images in there, and I just thought “Wow”; it was beautiful. So I contacted her and she agreed to let us use her images. PB: Again, the cover for that album is a very powerful image and a very beautiful piece or art, as you say. MG: Do you know how that’s made? Go to her website, beatricepediconi.com, and you’ll see a whole bunch of images that are like that. She builds a 4’ by 4’ by 4’ deep vat of water, and she has one those big, Hasselblad cameras – they’re 8x10, or whatever it is – suspended above the tank; she illuminates the tank, and then paints on the water. I think she’s amazing. PB: I have to say, I wouldn’t have guessed that! I assumed it was a depiction of a galaxy, or some other kind of astral imagining. MG: Yeah, that’s what I liked about it. I liked that, and then when I found out how she did it, I liked it even more because it was like this micro version of a macro universe, you know? Like a very small, delicate thing implying infinite space. But yeah, so it sort of works out like that. When I did 'We Are Him' (Angels of Light’s 2007 album), I was thinking about the artwork and then I remembered Deryk Thomas who did covers for us in the 90s, for Swans. I went to his website and looked and was like “Oh my god, I have to use this stuff!” So I called him and we did it. PB: That was the painting of the cartoon dog holding a bone, wasn’t it? That image is one of the ones I was thinking of when I mentioned your striking artwork before – it really sticks in the mind. That’s obviously a method that works well for you. To go back to the idea of a record as a package, the artwork is a pretty integral part MG: Definitely I grew up in the 60s and 70s, and the whole idea of an album, with the artwork, was always just really mysterious, and very tactile and the art informed the music and vice versa. I liked that a lot, I like that aspect of it a lot. In the same way, a title should resonate but not give up too much. It should resonate and imply something about the music. So they work and they reverberate against each other. PB: There’s a lot written about you coming out of the No Wave scene of the late 70s/early 80s… MG: That we were part of it? I wouldn’t say so; No Wave was earlier. No Wave was people like Teenage Jesus and the Jerks, Mars, the Contortions, DNA and Glenn Branca to a certain extent, although he stands on his own. Sonic Youth and Swans came later. By the time both of us moved to New York City, No Wave had already started to peter out. So we were kind of post-No Wave, and we really started our own little world there in New York. But I liked No Wave; that was on of the reasons I moved to NYC - that and the band Suicide. It seemed to me that really interesting, challenging and super-emotionally and psychically intense music was being made in New York City – as apposed to where I lived in Los Angeles, where it was kind of stylized punk rock. With the exception of the Germs, who were pretty shambolic, but they certainly weren’t any kind of grand statement musically. So there wasn’t anything, I thought, truly vital in LA, so I moved to New York. PB: I know some bands who came out of that scene, like Ut, had perhaps more of a following in Europe than in New York. It seems that quite often more experimental or underground bands from the US do better in Europe. MG: Well, that’s been the case for a long time; since the days of black jazz and things. Maybe it’s because Europe has – or had until the more recent crises – has government-sponsored arts programs that would allow an artist to come and play, and they don’t necessarily have to draw a huge audience, but they get compensated because the government pays grants to the organization, you know? But I guess that’s history for you, isn’t it? PB: That goes back to my earlier point about the similarities between now and the 1980s. MG: Yeah, the 80s were pretty bleak weren’t they? Particularly the early 80s. There was a long recession, and when I moved to New York City it was just rubble in a lot of places, at least where I lived on the Lower East Side, the East Village. Just rubble; have you seen those pictures of the South Bronx with crumbling buildings? That was how the Lower East Side was. It wasn’t quite as bad as the South Bronx, but on my block, every other building was abandoned, or inhabited by drug dealers. There was gun-fire, machine gun fire at night. Just incredibly dangerous; broken glass and bricks in the street. Taxis, of course, wouldn’t even come near where I lived. I got mugged with a knife to my throat – it was just a really dangerous area! New York was like 'Taxi Driver' in those days – which sort of made me want to move there, actually. PB: Was that a good atmosphere creatively? Did it inspire your writing in any way? MG: Yeah, maybe. I’m not sure how much my environment directly influenced me, so much as reaffirmed or confirmed who I was inside. PB: You already mentioned that you have started work on the next Swans album. Do you have any idea when that will see the light of day? MG: Oh, no idea – it’s just starting to coalesce in my mind. But there are sections on the new album, instrumental sections like the intro to ‘No Words/No Thoughts’, and there’s a long instrumental section in the song ‘Eden Prison’, I’d say that stuff is the beginning of what I’m going to move on to in the next album. PB: I wanted to say actually. The song ‘You Fucking People Make Me Sick’ has parts which really reminded me of the James Blackshaw album you released on Young God earlier this year. MG: You mean the arpeggiated guitar picking? That’s funny; that’s Christoph Hahn doing that guitar stuff. That song has an unusual genesis, in that it wasn’t a song originally; it was just a collection of sounds and scraping noises and loops, and it was meant to be a segway between songs - just a little, one minute thing. And I just kept adding stuff to it, or having people play to it, and building it up, and gradually I realized it needed an actual, melodic song in it. I thought that would be a nice interlude between these noises that were going on. And then I wrote this thing on acoustic guitar and I was singing it, and I realize I sounded like Devendra Banhart, so I got him to sing it. Also, it has my daughter singing. So it just kind of grew, and then it needed something at the end, so I had Bill Rieflin play piano and drums at the end; I had him do what he did and then I added horns on top of that. It just grew in the studio, as opposed to being preconceived. PB: So were the James Blackshaw-esque sounds that I was hearing influenced in some way by having worked with him recently, producing his album? MG: No, not really. I’ve been using those kind of clusters for a long time. I mean, James is different. He’s playing a kind of melodic idea that develops slowly over time, this is just playing open chord clusters. PB: Will Angels of Light be taking a sideline with Swans reformed? MG: Yeah, I have enough to do already, I can’t do two projects at once, so that’s taking a back-seat for the foreseeable future. I’m just going to pursue Swans until I decide to move on. PB: And finally, in terms of Young God – I know you said you weren’t going to sign up any new acts, but are there more releases scheduled this year from the artists you already have on your roster? MG: Oh yeah, there’s a fantastic artist who goes by the name of Wooden Wand; James Toth – do you know his stuff? Look it up on the net. He’s an amazingly gifted songwriter in my view. Along the lines of Willie Nelson, say. He comes from the indie world, but he has the elements of really great classical songwriting, storytelling songs. Like Townes Van Zandt, someone like that. Great storytelling, beautiful melodies. He’s just super, super talented – I admire him so much, I wish I could write songs like that. The songs are very dark, but they’re also funny. He’s really good, check it out. It’s going to come out in late October, and it’s called 'Death Seat'. But then that’s it. So I’m going to stick with the two Jameses and anybody else who’s on the label, see how that works out, and that’s it. I’m going to pursue Swans and my own music and that’s enough really. PB: Thank you.

Band Links:-

https://www.facebook.com/SwansOfficialhttp://swans.bandcamp.com/

Picture Gallery:-

interviews |

|

Interview (2013) |

|

| Paul Waller talks to New York-based experimental musician Michael Gira about taking his abrasive band Swans back out on the road again and their recent album, 'The Seer' |

| Interview (2010) |

live reviews |

|

KOKO, London, 15/11/2012 |

| Chrisn O' Toole watches reformed American post-punks Swans play an intense, but brilliant set at the KOKO in London |

| Academy, Manchester, 30/10/2010 |

soundcloud

reviews |

|

The Glowing Man (2016) |

|

| Overwhelming but repetitive double album and the final one in the present line-up of Swans before it calls it a day |

| White Light from the Mouth of Infinity/ Love of Life (2016) |

| To Be Kind (2014) |

| The Seer (2012) |

| The Great Annihilator (2002) |

most viewed articles

current edition

Carl Ewens - David Bowie 1964 to 1982 On Track: Every Album, Every SongArmory Show - Interview with Richard Jobson

Colin Blunstone - Thalia Hall, Chicago, 16/7/2025

Visor Fest - Valencia, Spain, 26/9/2025...27/9/2025

John McKay - Interview

Bathers - Photoscapes 1

Loft - Interview

Billie Eilish - O2 Arena, London, 10/7/2025

Robert Forster - Interview

Sir Tim Rice - Interview

previous editions

Heavenly - P.U.N.K. Girl EPManic Street Preachers - (Gig of a Lifetime) Millennium Stadium, Cardiff, December 1999

Beautiful South - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

Oasis - Oasis, Earl's Court, London, 1995

Pixies - Ten Songs That Made Me Love...

Prolapse - Interview

Boomtown Rats - Ten Songs That Made Me Love....

Trudie Myerscough-Harris - Interview

Coldplay - Wembley Arena. London, 16/8/2022

Peter Perrett - In Dreams Begin Responsibilities Interview Part One

most viewed reviews

current edition

Amy Macdonald - Is This What You've Been Waiting For?Sick Man of Europe - The Sick Man of Europe

Phew, Erika Kobayashi,, Dieter Moebius - Radium Girls

Lucy Spraggan - Other Sides of the Moon

Davey Woodward - Mumbo in the Jumbo

Alice Cooper - The Revenge of Alice Cooper

Bush - I Beat Loneliness

Suzanne Vega - Flying With Angels

Blueboy - 2

Cynthia Erivo - I Forgive You

related articles |

|

Paul Simpson: Interview (2017 |

|

| Paul Simpson talks to John Clarkson about his forthcoming memoirs 'Incandescent', his post-punk group The Wild Swans and his memories of late 70's/early 80's Liverpool and its bands |

Pennyblackmusic Regular Contributors

Adrian Janes

Amanda J. Window

Andrew Twambley

Anthony Dhanendran

Benjamin Howarth

Cila Warncke

Daniel Cressey

Darren Aston

Dastardly

Dave Goodwin

Denzil Watson

Dominic B. Simpson

Eoghan Lyng

Fiona Hutchings

Harry Sherriff

Helen Tipping

Jamie Rowland

John Clarkson

Julie Cruickshank

Kimberly Bright

Lisa Torem

Maarten Schiethart