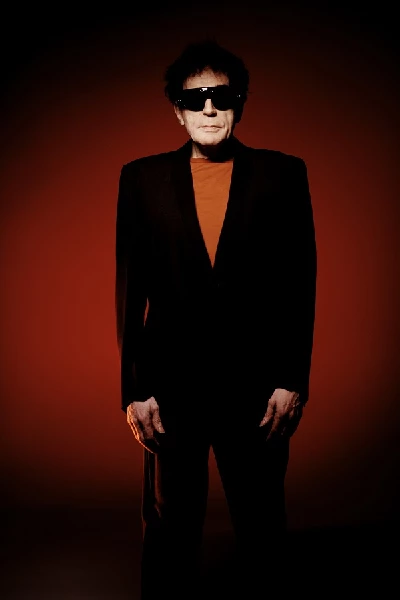

Peter Perrett

-

In Dreams Begin Responsibilities Interview Part One

published: 1 /

2 /

2025

In the first of a special, in-depth two-part interview, Steve Miles talks with legendary singer songwriter Peter Perrett about his new album, ‘The Cleansing,’ his life, his career, and why he doesn’t want to be resuscitated.

Article

‘I wanna die in the same place I was born/ Miles from nowhere’ – Peter Perrett, Part One.

‘We're born alone, we live alone, we die alone. Only through our love and friendship can we create the illusion for the moment that we're not alone’ – Orson Welles.

On Saturday, my two older girls and I sat down to watch ‘Citizen Kane,’ (written, produced, directed by and starring Orson Welles, 1947). They’d come over to help out at their twin sisters’ tenth birthday party.

I thought I had seen the film before, but I remembered nothing of it. I did ‘guess’ the ending a bit before it came, however, and I’m not clever enough to have done that, so I probably had seen it a long, long time ago, as I can easily forget things that happened seconds, let alone decades, ago.

Gwen (27) and Elin (25) had definitely never seen it, although Gwen and I watched ‘The Third Man’ together recently and both felt that Welles’ brief appearance in that had completely stolen the film, so we had high hopes for the famous classic.

It got stopped a lot as we watched it - sometimes to debate a bit, sometimes to clarify, but mostly to rewind where one of us had been forced by the film’s cleverness to say something about it while it was on.

We all agreed that it was fabulous. Not so much the plot, or the character of Kane - three parts Elon Musk, one part Welles, and one part their opposites – but the way it was made. So many brilliant shots.

By all accounts, Welles never reached the same heights again. It must be hard to peak at the first attempt.

We had Peter Perrett to thank for putting Orson Welles on the agenda, as he had spoken about him earlier in the week, when we had spent a few hours talking about the release of his new double album, ‘The Cleansing,’.

It shouldn’t have surprised me, because all the way back in 1978, when the raucous horn-and-feedback-drenched finale of The Only Ones’ debut album usually served as the cue for me to line up the stylus and hear the whole album again, that final song was called ‘The Immortal Story’ – which was also the name of a film from 1968 by Welles, though I didn’t know it then.

Welles was just starting out – he was just 26 - when he made Citizen Kane. A young man making a movie about a dead man’s life.

For Peter, making ‘The Cleansing,’ things were rather different. It is a record that has the genuine shadow of mortality running right through it, not as a ghost or an interloper, but rather, it’s a key theme of the record. It’s an album explicitly about the feelings you get as you near the end of life, when you look around at the world and what’s become of it, look back (with pride and regret) on what you have done with your life, and look forward to what is left, with a mixture of hope and fear. Its themes of mortality, survival, grief and passion are served up with ruthless candour and a superb clarity of production and arrangement, courtesy of Peter’s hugely talented son, Jamie.

The opening song, and first single, ‘I Wanna Go With Dignity’ signals the tone - not merely a steadfast refusal to crumble or wallow in the face of life’s challenges, but a determination to meet them head on.

The opening words, ‘It’s a losing battle, trying to be sane’ could come across as self-pitying, but here it’s just a matter of fact. And the chorus’ refrain, ‘I don't wanna overstay my welcome/ I wanna go with dignity’ reinforces the theme, as Peter looks death and depression squarely in the face.

Domino’s press blurb highlighted how the song took partial inspiration from two journalists who committed suicide, Fay Wolftree and David Cavanagh, both of whom Peter had met.

‘I met David Cavanagh in the early nineties,’ Peter tells me, ‘and I remember just one thing. He asked me, ‘How do you deal with the depression?’ At the time I didn't think that I was depressed at all, you know? I thought I was a carefree person. I thought I was just enjoying my life the way I wanted to.

The second time I met him was for ‘How The West Was Won’ because Domino employed him to write the bio in 2017. He didn't come across as being depressed - I remember him laughing at a joke I said, so I thought he was a jovial person. He had a sense of humour, but that's not the same thing, is it, as not being depressed?

So a year later when I heard he’d committed suicide – especially the way that he did, and with the preamble to it, the fact that he'd written a note on December the 23rd saying he was going to commit suicide, but he didn't want to spoil the Christmases of the train driver and the passengers on the train – that really struck me. Instead of coming back from that precipice, he just postponed it. You imagine most people who want to kill themselves actually do it as an impulsive action. I'm not a student of suicide, so I don't know what the motivation and the process is, but it just struck me that he, he spent those four days through Christmas - I think he spent it with his mum - and then just went through with it. I found it a very poignant display of determination and extremes - obviously it's an extreme thing to kill yourself but it is brave as well. I mean, I don't think I could jump in front of a train, no matter how I felt - I don't know.’

We’re a long way from dance party songs already, and we’re only at the chorus of the first song. But this is why Peter matters, of course. He’s an artist. And like most artists, although he’s keen to talk about his work, he’s also keen for it to speak for itself. There’s always a sense that explaining how songs were written or ‘what they mean’ can undo the very process of creating art, making the special banal, and leaving no room for the listener to meet the musician half-way. But at the same time, it would be very hard for any listener to know anything about David Cavanagh’s relevance to that song, for example, without some hint, which is why it’s a boon to have the chance to talk to Peter at length about the album. We covered a lot of ground, and in this two-part article I’m going to try to do justice to that as best as I can.

‘Most of us have known quite a few people that have committed suicide,’ he continues. ‘The third verse is don't go thinking there was something you could do - you know, when you hear that someone you know has committed suicide, you think of your last interaction with them, and was there something I could have done or said? And it's always self-recrimination: ‘Maybe I didn't reach out to them the way they wanted me to.’

At the end of your life, you sort of look back on and think about depression, suicide, euthanasia - you know, I'm a big fan of euthanasia – and so that subject matter that was close to my heart. I don't think, ‘I'm going to write a song about this’. It's just something that happens. And then if I'm feeling it, then I'll finish writing the song.’

That takes us thematically to the album’s ninth song, which is based around the wry repetition of the phrase, ‘Do Not Resuscitate’ and reaffirms in song the statements above.

‘If you get the chance/ Don't hesitate/ Send me on my way.’

In some hands, it might just be a joke, but death is a shadow that looms quite large in Peter’s life, as we’re discovering, and his sardonic treatment of the subject just confirms the album’s sober take on the challenges of age, infirmity, hope and hopelessness.

The song has quite an emotional story attached to it, which Peter told me, centering on his friend and neighbour, the Primal Scream frontman, Bobby Gillespie, who guests on the album.

‘That’s a playful song about choosing not to be without Xena (Peter’s wife), because she's had a DNR notice since 2015. If you're in hospital and they keep you alive artificially, you will never come off the machine. You'd never come off the ventilator. So, they give you the choice. And when I had COVID in 2021, they asked me that and there's no choice at all: who wants to be kept alive on a machine? That is not a life. So, oddly, it was quite an uplifting thing to know that you're not going to be kept alive in suspended animation, even though that’s heartbreaking to the people that love you, because it's better to fully transition to a better place. I wanted it to sound playful musically, that song, and so I told everyone to imagine that they were really drunk so that, musically, the instruments feel like they're falling over each other. And I told Jamie to try and make his guitar sound as unmusical as possible, so he's got sounds like machines being turned off, and Bobby's backing vocals are great as well. And I think it's captured perfectly the way I wanted it to sound.

But when he finished his backing vocals – ‘do not resuscitate’ in that high, sort of playful way – it was at my place, and when he switched his phone back on, it rang and it was a hospital in Glasgow saying his dad was there, and did he want to put a Do Not Resuscitate notice on his dad. And Bobby, me and Jamie, we were speechless - we just looked at each other. Sometimes things that no extreme coincidence could explain happen: how fucking weird that was, you know? I don't believe in the supernatural, but I'll always remember that moment, because that moment had far more gravity to it than my playful writing of the lyrics, you know? He went up the next day to Glasgow. His dad came out of the coma a couple of times, and he spoke to him. Uh, and then he died.’

Existentially, as well as artistically, this album clearly means a lot to Peter, as he explains:

‘At the beginning of Covid, we were told we were both clinically extremely vulnerable because of our lung diseases, and we were told not to go out, so the only time we left the house for 18 months was for hospital appointments. It felt very surreal. It did feel as with everyone else, like a dystopian science fiction film, and lots of people probably found it really difficult. But that's all I'd done for three decades: sitting in a room staring at the walls, living totally inside my own head, in my own universe - because what's comfortable about drugs is that you can create your own universe in your head and experience all sorts of things: like the matrix, you're plugged into something and it feels wonderful. You can live any dream that you want to live. But the only difference was I didn't have drugs. So, you know, it became Netflix, which, you know, is quite a benign addiction…and like I said, with the phone, you suddenly start talking to people that live in different countries and it feels quite safe. You can fall in love with people that aren't present, and it's not quite as complicated, so there's tons of inspiration, even stuck in a room.’

‘Then in September 2021, we were told for the first time that we could go out of the house. And so I went out, didn’t come home ‘til 4 am, and got Covid. And by November 1st, I was in UCLH hospital. It was depressing enough not being able to walk; I had to do so many exercises in bed to the point where I could exercise out of bed. And I was like doing 600 exercises a day. But it was disappointing, from being on the point of recording my new songs and having it snatched away from me.

Going up and down stairs with crutches is really complicated: when you've been walking naturally for like 68 years, 69 years, and then you've got to learn to do it again, you've got to think about it. And that’s quite difficult, but it's sort of character building: I demonstrated my willpower to myself, so by the time I did put down my vocals, I was like in a good place. And it just felt like the whole process had a gravitas to it. It felt like I was doing something important because it emerged from adversity. The adversity of having it snatched away from me, you know, the week before I was meant to go in the studio, then all the hard work just to get in a physical condition, to be able to stand up at a microphone.’

‘It felt like a major achievement. And it just felt like the whole process had a gravitas to it. It felt like I was doing something important because it emerged from adversity. The adversity of having it snatched away from me, you know, the week before I was meant to go in the studio, then all the hard work just to get in a physical condition, to be able to stand up at a microphone. It felt like a major achievement. And even though my mind isn't as agile as it used to be, I think I've maintained good taste as far as what constitutes good lyrics and I think I've got better at identifying good, minimal arrangements. I used to be very lazy approaching arrangements because I just write songs on guitar, jam them with the band, and that would be the arrangement. And there's only so many times you can do that without feeling repetitive. So I really enjoyed the fact that there's different approaches and I encouraged Jamie to experiment production-wise, you know, putting drums through guitar pedals and through an amp and so on.’

‘It just felt like a major project compared to the way I normally approached recording songs, and I think the songs deserved a more open-minded, experimental approach to them.

It feels like a real emotional experience for me to actually get it out there, and to be proud of what I've done.’

I’d never interviewed Peter before, but I had been in the same room, so to speak, as him about half a dozen over the years. I first saw The Only Ones in 1979 at a gig notable for a large and very hostile skinhead presence, the support act (Peter’s wife’s sister) being forced off stage by a disgruntled crowd after only a couple of songs, and my Dad being made to wait outside for hours to pick me up, as the band didn’t come on stage until after the gig was due to finish and I wasn’t missing this for anything. That was the infamous occasion when, after I finally came out hours late to get picked up, my dad revealed that he had, infuriated by waiting, come into the gig looking for me. ‘Why were they all throwing little bits of paper at the stage?’ he asked me. ‘Uh, they were spitting, Dad,’ I replied.

I saw Peter again 25 years later in Bristol when he returned with his band The One and hung around after backstage to quickly thank him ‘for enriching my life’, which he looked pleased by. That was the gig when I remember that I laughed out loud, hearing ‘Deep Freeze’ for the first time and delightedly thinking, ‘Which other lyricist in the world is going to use the word ‘cryogenic’ in a song, and even better in a pun?’

A decade or so later I saw him in The Only Ones’ reunion in London, as captured frequently in the crowd shots on the DVD, in lulls between the running aggro I had with a fellow gig-goer who insisted on bellowing along to every word, when all I wanted to do was hear Peter’s voice again.

Then another decade or so later came a couple more gigs where I again lurked around after, this time to tell him that I now had four daughters, and that I had played them all ‘Another Girl, Another Planet’ in the womb with headphones on their mums’ tummies. He wrote on the back of the setlist, ‘To Gwen, Elin, Florence and Felicity, lots of love for 2+2 girls on this disintegrating planet of ours,’ which I have framed on my wall.

Of course, he didn’t remember those brief fan encounters at all, and when I told the last story he was shocked anew.

‘Oh God, that’s a terrible responsibility! It’s like someone once told me that because in the song ‘Trouble In The World’ I wrote, ‘Don't be scared to have children/ Anyone would have thought it was pre-ordained,’ they decided to have a child after that. That's a terrible responsibility.’

So, we’d never properly spoken, but I had already written at length about him in a previous article for this column in 2021. I wasn’t going to mention that when we spoke because I was afraid that I’d got it all wrong, and he’d hate me. But I had a very pleasant surprise, because our phonecall began with Peter telling me he’d literally just finished reading what I’d written back then.

‘I've got to say I'm touched and humbled that you deem me worthy of such deep analysis,’ he began. ‘I don't know what to say, it feels like I've gone through a series of psychotherapy sessions that I would have had to pay hundreds of pounds for. Thank you. I thought, God, this guy actually gets what I'm trying to say and takes it seriously.’

I won’t pretend I wasn’t touched by his words. I was. But it was only later that I realised that I’d been working towards that my whole adult life, in a way: I recalled that when I was at school, for part of my English O’Level, we were allowed to make our own anthology of favourite poetry and write about why we liked it. I think I had some Keats in there, some Thomas Hardy, a sneaky quote from Catch-22, and, of course, some of my new punk records’ lyrics in there too, preposterously convinced that I was subverting the entire established order by doing so. I had a bit of crap from Siouxsie and The Banshees solely because the NME told me it referenced RD Laing, and I’d read him in response, and thought it would seem clever in the exam to say so. I ought to have had some Pete Shelley, since I was obsessed with The Buzzcocks at the time, but I suspect I didn’t think him literary enough. Perrett obviously qualified as literary, suavely using words like ‘soignee,’ ‘firmament’ and ‘dissipate’, so I quoted a couplet from the imperious ‘From Here To Eternity,’ ‘All that glitters is not gold/And even serpents’ shine.’ It was only later in life that I felt embarrassed by that attempt to be clever, when I realised that the first half of the couplet misquotes Shakespeare, and the second half makes no sense at all.

But then, we were all young once…

As Peter said at the album’s Q&A launch at Rough Trade, ‘What advice would you give to your younger self? That is such a loaded question. The problem with that question is that I wouldn't have listened to any advice. When you're that young, you're so arrogant, you think you know it all. And you've got to find out everything for yourself. And there are some things that maybe people with more wisdom who have experienced it could share, but back then it was like just living every day for the ultimate experience. Just chasing fun all the time… It's one thing to be impulsive, but you've always got to be aware of consequences. And when you're young, you don't care what consequences are.’

Does it feel, I asked him when we talked, like ‘The Cleansing’ is the record that you've put the most into?

‘Oh, definitely,’ he concurs. ‘For a start, it's 20 songs. The older you get, you sort of reflect on your life, realise that maybe you haven't been particularly productive, and that maybe that's something that I owe to myself and to my wife (Xena), who is my biggest fan. I mean, she is the person that propels me into the maelstrom that is the music business, you know, because everything about the business I hate.

I hate demands on my time and having to do work. To me, music is just fun, and it's what I get a lot of pleasure from, but the expectation just leads to disappointment. To me, that's a pressure that I'd much rather not have to indulge myself in.

I'm getting profoundly deaf, and in small clubs, the monitors are so shitty, I can never hear them. So, yeah, there's all these new challenges, which at the age of 72, I'd prefer just to laze about at home, really. But as far as making the album, yeah, I took it very seriously because you never know if it's going to be the last thing you ever do.’

‘There for you’ is another song about someone that was lost. This time, ‘A family friend who was in a hospice, and my desire to visit (Jamie visited, and held his hand as he died). It’s about the difficulty of communication in certain circumstances, when dementia is involved.’

‘Too late when people die/ Run out of time, they're out of time’

‘And sometimes, as you get older, you sort of find yourself just doing stuff because people ask you to do it. What was great about this album is it was done at my own speed. As soon as I could stand up without crutches, just stood at home with a microphone, I put down a rhythm guitar and vocals. So this album started with the vocals. Previous albums, you know, producers, you know, spend a day getting a drum sound and stuff like that. But this started with the vocals. I finally went in the studio July 2022, to put down the backing tracks to my already recorded vocals. And then Carlos got involved, and he started doing things to some of the songs, which would have been outtakes. He wrote, like, string quartet parts and piano. And it just made me reflect on the songs more. You know, lyrically, I'm really happy with every word on it.

Is the speaker talking to you in ‘Less Than Nothing,’ I ask him?

‘You know, so much about me!! First person, second person, third person – they’re all interchangeable in my lyrics. Sometimes when I say you, I could be talking about myself; when I say he, I could be talking about her. So, yeah. That’s a dumb song I wrote by way of an apology. I wrote ‘Carousel’ (from ‘Humanworld’) right at the beginning of the nineties about a relationship I had - someone that I wrote a lot of ‘70s songs about: ‘From Here to Eternity,’ ‘Love Becomes A Habit,’ and ‘Why Don't You Kill Yourself?’ - which I sort of regret cause it was reverse psychology, but it might not be interpreted that way. It now seems a bit too flippant a sentiment to express that way.’

In the song, Peter gives voice to his ex (and maybe his conscience) as the song’s narrator chastises both his original behaviour and his attempt at reconciliation and self-justification in ‘Carousel’.

‘And that dumb song you wrote/ By way of an apology/

Deep in the shadows hidden by a cloak/ And a bizarre notion of chronology/

It means nothing/ It's worth less than nothing.’

You can see he’s learned a lot since the earlier days, and isn’t holding back. It is harshly self-critical, but he’s not hiding it from us:

‘Every word that you said/ Every person you loved/ It means nothing.’

It’s damning stuff, but still the notorious romances alongside his marriage remain.

‘On the first (solo) album, there were four love songs, and they were all about Xena, he explains. ‘I can't just keep rephrasing my feelings for Xena. So I do search for other romantic subject matter, which sometimes is fantasy. Other times, it's all real - even fantasy is real, real people.’

‘I don't know, you look like someone I could love’ he starts with on ‘Feast For Sore Eyes,’ within which he continues the love-as-travel metaphor he often employed in Only Ones’ songs:

‘Unprepared for this trip/ Don't recognise who is steering the ship/

A great adventure into the unknown/ I'll go anywhere, if it gets me home’

This gets further mention when we talk about the song ‘Mixed Up Confucius’, which benefits from the context he gives:

‘That's more of a stream of consciousness. The first two verses are completely different to the second two verses. The first two verses… I think I'd seen a documentary about Hemingway. I wasn't consciously capturing it, but ‘Clear the clutter/ Blow your brains out’ could have been subconsciously influenced by his momentous decision to end his suffering. I think just before that, he tried to write an address to Kennedy, and he could hardly read: his brain was in a terrible state. I can empathize with that - when you’re proud of your brain and its ability to function, it can be quite dispiriting.’

Notably, we have here another deeply complex artist referenced on the album, one whose life mirrored Peter’s in many ways, and who, like others mentioned on the record, killed himself. Terribly, it was the thoughtless, repeated use of ECT, at almost the same time as Lou Reed was being ‘treated’ with the same barbaric practice, that both fried Hemingway’s mind and prompted his suicide.

‘You're just an old man/ Who went too far out to sea/ this time.’

‘That’s sort of an allegorical tale of the artist. I think it speaks for itself, you know, because he went so far out to sea that, and caught his big fish, but by the time he got back, it'd all been eaten away.

And then halfway through writing that song, I met someone - through the wonderful invention of a mobile phone and social media (which I'm being ironic about because I think that the mobile phone and social media are terrible inventions that just bring a lot of heartache and anger) so the last two verses are about that person. Oh, I'm being too honest - I can't help it! So yes, that person, I also wrote ‘Secret Taliban Wife’ about. She's not from Afghanistan and there aren't any females in the Taliban anyway. But it was just the sort of thing that idiotic people come out with to be insulting. Um, I’ve probably disclosed too much – because, as you pointed out in your original article, I like things to be ambiguous. And when you reduce them to a specific narrative, then it takes away the ambiguity. You know? Words should spark the imagination. And once you explain them, it demeans them, I think.’

And leaving them open to interpretation, of course, also protects living people who might or might not be depicted in the song… I don’t, accordingly, ask Peter for any background about the song ‘Disinfectant’, which employs more medical references in unlikely ways and presents another pretty bleak view of his romances:

‘She suffered from PTSD, from a young age/ They say “love's a disinfectant, wash the hurt away"/

I told her I loved her…/ She knew I didn't believe me.’

Or, as the lead character, played by Orson Welles, states in ‘The Lady From Shanghai:’

‘When I start out to make a fool of myself, there's very little can stop me. If I'd known where it would end, I'd never let anything start... if I'd been in my right mind, that is. But once I'd seen her, once I'd seen her, I was not in my right mind for quite some time’ –

Elsewhere on the record, ‘Survival Mode’ is about the dangers of social media, while ‘World In Chains’ reboots a song first demoed in 1990. Although the much-repeated refrain offers no specifics as to the nature of those chains, given Peter’s clearly articulated political perspective (at one point, he remarks, ‘I've said before that the day of the Brighton Bombing was my happiest day in the ‘80s and I got into trouble for saying that on the radio and had lots of complaints’) it doesn’t take much imagination to name a few of the potential jailors.

There’s ‘no insurance policy for broken dreams’ he croons, and whether that’s for love or for revolutionaries, the sentiment rings true.

‘All That Time’ is one of two songs on the album, along with the title track, that specifically refer in part to the years of his well-chronicled addiction, and it’s one of the standout tracks, with a great arrangement by Fontaines DC’s Carlos O’Connell.

‘The thing is, if you're in heaven the whole time, then you've got nothing to compare it to,’ he says. ‘I think you need the ups and downs and the confrontation with the real world to actually enjoy the moments that you escape from it… I was trying to get across just the ridiculous boredom of making that choice every day. Because it's about waste. And I go back to it, because in your earlier article about me you quoted ‘Don't Hold Your Breath,’ ‘Every wasted moment serves its full purpose’.

I mean, it is an experience. Not many people survive in that experience for such a long time. Literally 35 years of it - you know? I had a month off in 1985 in rehab. I had like comparative cleanliness for a short while in the ‘90s. But what's so stupid is that at the time, if somebody questioned me, I thought I was having a great time.

And Jamie just looked at me and said, ‘I thought you were just really depressed’. You know, a child can't tell you that. Do you know what I mean?

You feel the absurdity of it. The theatre of the absurd can be a very entertaining place when your perspective is from a distance: when you're actually involved in it, it can seduce you into thinking that you're having fun. So I think it's a great song because it's the truth, but it's about a pretty pathetic subject.’

Peter lives in the building that was once the old Pathway Studios, famously used by Stiff Records in particular, so we talk about that for a while.

‘We've got tons of vintage stuff because obviously I'm old. So I've got lots of old tape machines, you know, Echoplexes, Roland, Space Echoes - loads of vintage stuff, but, you know, in some ways it's like a, a burden because they're so beautiful to look at, that they fucking cost a lot of money to, to maintain and to service. But sometimes with modern computer stuff, people are used to hearing perfection, you know, no mistakes. But I get attached to some mistakes, you know, and that's the only conflict that me and Jamie have: I'll get attached to something he's done on the guitar and not want him to do it again. And he'll say, ‘Yeah, but I did that by accident, people can tell,’ and I’ll say, ‘Yeah, but it sounds good, it sounds like it should.’ In the old way, mistakes were on every record, because you just had to choose the best mix, and if that was something where someone had forgotten their cue, then you just went with that, because you just went with the best that you got.

It is nice to, to aim for perfection, but not to get lost in technical perfection, you know? I like a bit of leakage sometimes because it adds a bit of mystery, whereas engineers have to think about other engineers listening to their work and criticising their capabilities… But, still, we've taken advantage of, of computers, digital, but hopefully it sounds warm, because like I said, we do use a lot of vintage stuff as well, so, I think the combination is great.

It’s clear that Peter and I have a lot in common (in our hearts and minds - our lives could really not have been more different): from a mutual love of the Velvet’s ‘I Heard Her Call My Name’ (‘that's what the electric guitar was invented for, to make that fucking noise’) to our shared fondness for mistakes and imperfections in music; from our high ideals (‘I've never considered that music should be about entertainment, it should be much a much deeper experience than that’) and the discovery that we both adore the unheralded one-album genius of Canada’s Mary Margaret O'Hara.

When I mentioned her, I didn’t expect Peter to have ever heard of her, but of course, it transpires, he knows her personally.

‘The first time she phoned me, she phoned me just out of the blue. Oh, I was in tears. I was in tears because I was briefly clean at the time her album came out. I think it was close to when Lou Reed's ‘New York’ album came out. When you're clean, you want to listen to music again.

And then I saw her at the ATP festival we played at. She was on a little stage, and I was at the front, and I was just crying. And that's never happened to me, especially given the fact that I was still taking drugs. But there was just something about the fragility of her as a person. I can't remember if she ever completed a song, because she would just walk away from the mic in a sort of circle, and the drummer would say, ‘Please come back to the microphone, Ms O’Hara’. It felt like she was on the edge of just falling off totally, but it was the beauty in her voice.

After that, after seeing her there, she got my phone number off somebody, and I heard her voice on the phone, I was in tears, you know?

Just speaking to her on the phone, you could tell that she was in a different place to most of us. And funnily enough, someone sent me an article on her from the late eighties. The big headline was Another Girl, Another Planet. They chose that to describe her because she's so eccentric.

But my favourite thing, which I discovered at the beginning of lockdown, April 2020, right at the beginning, is a song called ‘Out Of The Blue’. I'd never heard the original Robbie Robertson thing, but I heard her version and it just made every day better. I listened to it four or five times a day in lockdown, it's just so relaxing and so peaceful and beautiful. And then I thought out of interest I’d listen to the original and I got through about 30 seconds - I thought, I don't want to spoil this song! This is Mary Margaret's song. Do you know what I mean? Don’t listen to the original, Steve, it'll depress you. It’s like it was written for her.’

The conversation turns back to my earlier piece about him.

‘You said, ‘The enemy we're fighting/ He's inside of you and me,’ and you said it was from Prisoners, but it was from Oh Lucinda (Love Becomes A Habit),’ he corrects. ‘And then you were talking about songs from ‘Remains’ having unclear provenance? Well, lots of the songs were demos that were done before The Only Ones, so, they were like from ’74-75, particularly ‘Don't Hold Your Breath’. And you quoted lyrics from that. And I thought, ‘Wow, God, I could write lyrics back then!’ Do you know what I mean? You tend to dismiss the stuff that you've done when you're really young, because you think ‘I was immature, I didn't really understand’. But yeah, there were some impressive words in it that actually described my personality. It was nice seeing that I could actually write lyrics back then.

Like when you first start, you write songs around two chords and stuff. And then pretty soon you learn more. So what might be musically sophisticated is just me trying to go to different places before I started. And even with The Only Ones, some of the things are more complicated than they should have been. Like ‘Lovers of Today’ has got bars of 5-4, 6-4. And it was only when I was trying to teach it to The Only Ones that they said that, because I wasn't aware of what a bar of 5-4 or 6-4 was! You realise that you must play it the same way, otherwise it confuses people. So, I started analysing what I was doing more.

Oh yeah, you mentioned about ‘Silent Night’. Yeah, that was done for a Dutch radio show, not Belgian. In 1979, we were on tour in Holland and they asked us to do a Christmas message. And I hate saying, ‘Oh, this is Peter Perrett from The Only Ones. I hope everyone has a happy Christmas’. Shit like that. So, I thought, we'll do some music.

And ‘Silent Night’ seemed like a good thing to do. But we tended to be late for stuff. So, we got there five minutes before the session, so, we couldn't have a run-through. We just played it live. So, we sang the first verse and then it came to the second verse. And I realised I didn't know any other lyrics to the song at all. I didn't want to just repeat the first verse. So, those lyrics to the second verse were made up on the spot. There's one line where I sort of hesitate for a bit before coming out with the line, because my brain was trying to work really quickly to think of what I was going to sing. But I'm glad you appreciated it.’

At one point in our conversation, I suggest, tongue in cheek, that if Peter doesn’t explain a particular lyric to me, I’ll have to write about it anyway, and probably get it wrong.

‘So you're acknowledging my preference for not explaining lyrics but you're trying to throw in one more,’ he jokes. ‘Like I said at the beginning of our conversation, I am touched and humbled by the depth to which you analyse my stuff, and I think you could probably analyse what it's about better than I could remember what it was about when I wrote it. Seriously, I’m in awe of your understanding of my lyrics.’

At which, I humbly ask for clarity over some lines in ‘Shivers,’ a song that I have loved for a long time. The song celebrates many of the things, some very serious, some playful, that make life worth living for Peter. But there are some references that have always frustrated me, like the opening line…

‘So that’s ‘Face of miner/Strains of Jerusalem’, it’s ‘miner’ with an ‘e’ not with an ‘o’. The first bit of that I must have written when I came out of rehab, so it was the time of the miners’ strike. They used to have a program called ‘What The Papers Say,’ and they showed Arthur Scargill arm in arm with Winston Churchill Jr, can you believe? Winston Churchill Jr was marching with the fucking miners! And it was very emotive because I’d come out of rehab, so I was feeling things really strongly again, and over the closing credits was just the face of a miner with all the grime on his face, and they played the song. It was emotional enough for me to actually write that first line from there and then I carried on writing the song.’

The song gives a ‘shout out’ to Peter’s revolutionary heroes, such as The Little Rock Nine, Tommy Smith’s black glove, and the VC Tunnels that kept the VietCong safe and mobile while the US carpet-bombed their country.

‘The Vietnam War, for my generation, was so momentous and so emotional. When you saw that last helicopter leave Saigon, you thought, ‘Yeah, good has triumphed over evil and it will never happen again,’ but of course it did.

‘I don't know what the Santiago singer's one hand sound is either,’ I admit.

‘Oh, he's a famous Chilean folk singer, Victor Jara.’ [I subsequently find the story in a 2019 Netflix documentary ‘Massacre at the Stadium’] ‘It must have been the same time that I had just come out of rehab because I was listening to the radio and they played him singing ‘Guantanamera.’ It’s quite an evocative song anyway, and to hear him singing – his defiance against the oppression of a fascist dictatorship - was inspirational.’

Retrospectively picking better couplets to quote to my O’Level teachers, and seizing the opportunity to talk, albeit much too briefly, about The One’s massively underrated, if imperfectly produced, album ‘Woke Up Sticky’ (1996), I mention the great lines in the opening track ‘Deep

Freeze’:

'The collapse of communism/ It's like the crucifixion of Christ/

You make the same enemies/ You pay the same price,’

and he clarifies that, ‘the “same enemies” are a) Imperialism...American/Roman, b) Religion and its hypocrisy...scribes and pharisees, and c) Capitalism - throwing the money lenders out of the temple. I regard Jesus (it's more than likely that he did exist),’ he adds, ‘as an early socialist.’

The opening lines of the same album’s ‘Nothing Worth Doing’ are, ‘Angry that I'm here/ Didn't ask to come,’ and he agrees that this is about ‘life itself, or a specific point in life. Sometimes I just write lyrics and try to work out what they're about later. Variations in interpretation can increase with the passage of time. This applies to most songs.’ The same album’s ‘The Law Of The Jungle’ contains the great line, ‘The squalor of success, the luxury of failure,’ which Peter confirms, ‘Is a brilliant line (in a song containing many brilliant lines) - 'success' can lead to a squalid, detached disposition, and the acceptance of 'failure' is a luxury.

‘Before I used to write songs, I'd sort of write the words and think, oh, they're perfect. But because obviously quite a few of the songs were written in lockdown, I had a lot of time to focus and to concentrate. Yeah, so I'm really happy with the album.

And I feel like it is a combination, because I think I've reached a point where I'm able to specify, to express my innermost feelings. And like we were talking about frontal lobes shrinking - they say when people get old, they lose their filters. I don't know if I ever had filters. I think I did. But there's a sort of a naked truth about everything that I write now.

I'm loath to say, ‘Oh, it's my best album ever,’ because everybody always says that. And you have to feel that, otherwise, why record it? I can't understand anyone who just goes through the motions of fulfilling a demand from a market. You know what I mean? I can understand it because they tour it and they make money doing it every two or three years or whatever.

But yeah, it does feel like the most important record I've made. Because I've had time to reflect on it. And I still love every word and every note. And hopefully it will grow on you even more. I'm hoping it's a journey. Your article said, I like to think of albums as being journeys, and I think that of this one in particular. I'm really proud of the sequencing of the songs. And hopefully when you listen to ‘Crystal Clear’, you want to go back to the beginning again.’

This is a reference to the confessional last song on the record:

‘You’ve got to own the choices you’ve made/ You thought you’d teach them all a lesson/

But it seems you weren’t that clever.’

He adds, ‘I thought it may be appropriate, or desirable, to have clarity at the end.’

But does he mean of the album, or of life… or both?

In part two of this interview, coming soon, we continue to look back over the life and thoughts of Peter Perrett, taking in his observations about the likes of Johnny Marr, Bob Dylan, his family and The Spanish Civil War along the way.

Photos by Steve Gullick,

Article Links:-

https://peterperrett.com/

https://www.facebook.com/peterperrettm

https://www.instagram.com/peterperrett

https://x.com/thepeterperrett

Play in YouTube:-

Picture Gallery:-