published: 19 /

1 /

2024

Los Angeles composer and arranger John Philip Shenale is associated with Grammy-nominated artists: Tori Amos, Jane’s Addiction, Tracy Chapman and Billy idol. To celebrate the 25th Anniversary of ‘Night of Hunters,’ he shares excerpted highlights of his five-decade career.

Article

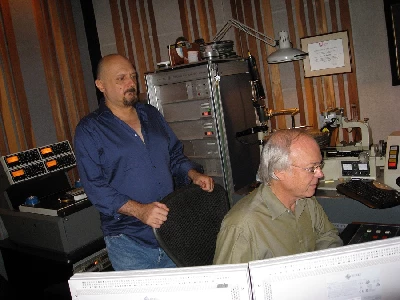

Capitol Mastering Photograph of John Philip Shenale and Ron McMaster by M. Woodhull

“I’m addicted,” the SoCal musician confides over Zoom, yet not to the obvious culprits: pharmaceuticals, booze or sports cars. John Philip Shenale’s condition, however, is as visceral as a runner’s racing pulse. Fueled by filtered Dickerson’s blend at noon, his addiction powers him through twilight conversations with singer-songwriter Tori Amos or battling NYC traffic for a pre-production meeting in Soho.

Some artists would be shattered by his “long day’s journey into night” regime. He recently revealed that he had been revising rough cuts for, what sounded like, a hot shot client. Despite editing for hours on end, when we caught up, he sounded remarkably renewed.

Taming a melody into a masterpiece takes diligence and drive. A flick of the bird to sleep. But fortunately, for this triple-hyphenate’s fans, John Philip Shenale remains, arguably, addicted…to music.

The A-listers that make up his mile-high biography is legion. They verify his versatility as a creative. This influencer collaborated on Janet Jackson’s ‘Dream Street,’ arranged Bette Midler’s poignant ‘Lullaby in Blue,’ pumped up Bonnie Tyler’s ‘Holding Out for a Hero,’ and created an alien orchestra for Jane’s Addictions’ ‘Then She Did,’ among other projects. His partnership with Tori Amos, which began in 1989 has flourished for thirty-four years plus.

Raised in a musically-supportive household with stringed instruments at the ready (his father was a multi-instrumentalist), he, actually, fell in love with the church organ during High Mass back in Toronto, Canada. Once his family settled in L.A., the pre-teen started conventional piano lessons. Similarly, to his parents, he extended his knowledge through self-teaching, but also racked up college credits in music theory.

The twenty-first century quick study, dubbed “Phil” by a select few, has survived the slings and arrows of an arguably tough industry through perseverance, gut instinct, an exceptional ear for contrapuntal beauty (‘Stars That Speak’) as well as dreamy dissonance (‘Battle of Trees.’)

Originally slated to be a physicist, he is apt to combine scientific expertise with profound musical proclivities, His work as a “prepared pianist” (on John Doe’s self-titled debut; with Amos on Grammy-nominated albums) solidifies the point.

In this Pennyblackmusic interview, John Philip Shenale shares studio highlights and examines the art of transitioning through trends. His heartfelt advice, honed across five decades of hard work and productivity, is evergreen:

“To be professional, allow for surprises. Stay open to opportunity. Stay ready.”

Stay ready, Pennyblackmusic. Here’s John Philip Shenale on arranging, producing and more.

PB: Some children squirm during a liturgical service. As a small child, why were you captivated?

JPS: My parents had always surrounded me with songs and readings and thoughts. They provided me with a child’s record collection of music from around the world, both classical, country and folk, Far-east, Middle-east and everything, but it was presented in a child’s format.

I had my own Philco portable record player to play my music.

When I was about four or five, at a very significant moment, I went to church. It was a High Mass filled with a choir, pipe organ music and singing. So, when I got home, I started playing the piano, imitating the Gregorian style, which is basically movements of fifths, movements of octaves and some counterpoint. I basically imitated what that choir was doing. That really captivated me.

Dad preferred Classical music and I was just fascinated by it. But I didn’t take piano lessons until

I was about twelve. There was a theory going around that at that age, you’d really know if you wanted to do it.

My teacher’s hands were so big, I mean, beyond like, normal hands. And he had these little pads on the bottom of his fingers, like alien hands. As a child, I was so fascinated when he played—he was a big jazz-er. So, he was playing these tenths and elevenths and these inner-voicings. He didn’t play too much because it was my hour, but I would ask him to play because I was fascinated by these huge Oscar Peterson-style hands.

I started reading scores. My mother would take me to Pickwick’s in Topanga Plaza in the San Fernando Valley and buy songbooks and eventually scores for me to study. In high school, I would listen to classical music, trying to figure out how to read scores and interpret what I was hearing to what I was seeing. Then I would try to imitate these feelings that I got from listening to Debussy, Ravel, Stravinsky and Mendelssohn.

That was my early music education. I am pretty much self-taught in terms of theory, composition and arranging, although years later I did take classes in Schenkerian Analysis, expanding my perception and understanding of theory and composition. It was conceived in the early 20th century and concerned with 19th century common practice but it still provides me clarity in the 21st century.

The piano lessons which directed me—the basic principles are universal. No matter what level you are in piano, there are certain principles which I practice to this day.

PB: After high school, you gigged in California. What was the club scene like back in the 1970s?

JPS: Massive. Not only because there were a number of clubs, but it was healthy enough to support bands, both covering Top-40 material, but also original material, which would actually allow the musicians to pay the rent, buy food and pay for a car. It was an economic model which worked in Los Angeles from the 1970s until the early 1980s when the whole thing fell apart because of DJ-type clubs. I never worked a day gig.

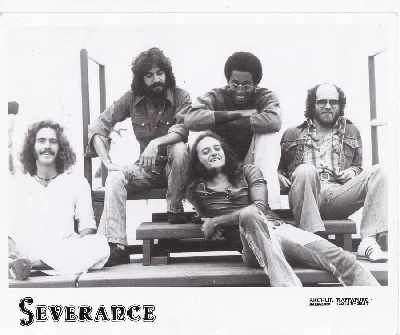

But the exception was when I worked with Gregory Hines in Severance. We only played original music. It’s amazing because you can hardly find a cover band anymore barring a handful of tribute bands.

PB: You get a call from a famous band that wants you there yesterday. The Beach Boys. You had little lead time and you weren’t necessarily familiar with their material. How did you prepare?

JPS: It was sudden. But there was something percolating for about a year because my introduction to The Beach Boys was actually through Mike Love. He was putting a band together and he needed a keyboard player to replace the musician that was leaving.

So, I met Mike in Santa Barbara and told him about my interest in electronics and technologies, among other things. We had lunch and I didn’t hear anything from him again until about a year later. Then, I get a call, ‘Yeah, we want you to join The Beach Boys.’

It wasn’t really an audition. It was like, ‘You’re in The Beach Boys.’ I went to Brother Records, a studio in Santa Monica. I just hung out. They were playing music. I was sitting on a bench. They’d play a little bit and talk most of the time. People were walking in and out. Dennis was there most of the time. ‘Here’s a list of songs.’

For two days, I just listened. I dumped every song on the list onto my cassette recorder and I just started studying. Most of the material is pretty easy, but there are a couple of doozies in there: ‘God Only Knows’ is one of my favorites, but fairly complicated. There are some simple ones, like ‘Surf City’ or whatever reiteration they did of ‘Surf City’ with different lyrics.

Then I got on a plane two or three days later – it was a big stadium in Minneapolis. In retrospect, it was probably about 85,000. My first “big” gig. After playing in clubs with about 200 people max, that was something else entirely.

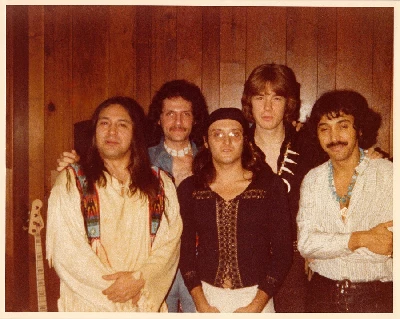

Eventually I learned that it doesn’t matter how many people you play for. The gig is either going to suck or it’s going to be great. You have no control over anything except your performance. So just play. After the Beach Boys, I went on to play with Redbone.

PB: You ended up being in a group of sought-after synth players at a certain point, didn’t you?

JPS: A group of maybe a dozen including Steve Pocaro, Michael Boddicker and Bill Cuomo.

PB: That’s impressive.

JPS: The only “synthesizer” I could afford back in the early 1970s was the Vako Orchestron, an optical-based Chamberlin-like keyboard. By the time I got my first synthesizer, the Oberheim 8-voice SEM, the first polyphonic synthesizer that was programmable, I was well-versed in synthesizer technology. I had accumulated a large collection of synthesizer operation and design manuals over the last decade.

In 1982, I received a call from Giorgio Morodor’s assistant who I met while playing with Severance. She said, ‘Hey, Phil, remember me? You were always such a madman about synthesizers. I told Giorgio about you.’

Coincidentally, I had started investing in synthesizers and various pieces of gear and samplers and really started my exploration of sound, electronics and programming.

This was one of the branches of my career. I eventually met Richie Zito (Cheap Trick, Joe Cocker, Cher), a great guitar player. Then, I met Davitt Sigerson, who was producing David and David and then produced The Bangles and Tori Amos.

All I knew was that I loved music and I loved electronics. I did everything I could do to play. I worked as much as I could. I would be in club bands and I would be studying electronics. The guys would be going out to the park or the swimming pool or the beach, but I would be practicing all day in the club, smelling like second-hand smoke for six hours on the stupid piano that was completely out of tune. By the mid-1990s, I had done something like 200 albums.

PB: During this time, you co-wrote and arranged Janet Jackson’s ‘Dream Street.’

JPS: Right. Which was just before her big record, ‘Control.’ I wrote the title song on ‘Dream Street’ with Pete Bellotte (Donna Summer) and it’s been charting this last year in Europe again.

PB: Robert Frost said: ‘Freedom lies in being bold.’ “Bold” reminds me of epic, ‘Yes, Anastasia’ off of Tori’s ‘Under The Pink,’ written about Anastasia Romanov, daughter of the last Russian czar. To me, this is the Russian Revolution set to music in under ten minutes. Or Chopin’s ‘Revolutionary Etude.’ You and Tori establish solid, singular lines, both instrumentally and vocally, that when merged are magical.

This must have been an emotional high. If so, how did you decompress?

JPS: That decompression is basically the story of my and Tori’s relationship (laughs). Compression and decompression. That is every record. Sometimes, I don’t decompress. In the mid-1990s, there was so much work going on, not just with Tori, but with others. That was so emotional.

In retrospect, I realized that I was not dealing with it well, in a sense; I should have been decompressing more. That’s all cool now, but I look back and think, I really should have addressed that.

PB: You can’t turn it on and off?

JPS: That’s the problem. But there’s a way of making it gentler. I’ve learned over the years – ‘Okay. calm down, Phil.’ For the sake of the music, for the sake of the composition and the art, you have to have a balance between the emotional connection and being the observer.

You’re feeling intense emotions but you have to stay balanced because you have to be present to write the music. There’s no formula. You just have to negotiate. And it’s different for every situation.

Sometimes, you have to be very observational and extremely accurate. Other times, you might be completely emotional and you throw judgment to the wind.

What I was not dealing with until the last couple of decades was that I was completely consumed in taking in this emotional thing. I didn’t know how to separate my internal emotions from the music and the emotional connections to the people around me.

PB: Carl Jung said: “Who looks inside, dreams, who looks outside, wakes.” Does that quote correspond with the process that you go through as an artist?

JPS: Yes. The dreamy part—that’s a good point. That’s the texture. So, there is the dream. And then, there’s the emotional component of the dream. Then, there’s the observational component of the dream.

So, actually, to live in the dream continually is my goal. Even in real life, which sometimes becomes something that you have to negotiate a bit because you can have a car accident. Basically, that is what my goal has been my whole life, to be able to create 24/7.

In other words, to live in a world of creativity. The dream is kind-of the vessel that holds the creativity and the observation.

PB: Some musicians keep a log of melodic fragments and concepts. How do you handle a new arrangement? Do you start from scratch or do something similar?

JPS: I do both. In terms of composition, there are two different applications of the creation process. In composition, it can happen any time. It can be a fragment and I record fragments all of the time.

Currently, I’ve been doing narratives in terms of words and stories. So, it’s a constant state of recording ideas. Some people have photographic memories. I don’t. I have to save everything.

That concept of ‘Oh, I’ve got this idea. When I get home, I’ll write it down.’ That never happens. I’ll tell SIRI ‘Text John Philip Shenale’ and then, I just tell SIRI my idea. So, it’s in my notes and my computers. Sometimes, I’ll forget about it and read my notes after a few weeks. ‘Oh, yeah, that!’ It’s such a blessing.

When I intentionally create something new, I create new sounds. I rarely store my patches on my synths. I program new sounds. I’m influenced by what the song is that’s right in front of me.

For an arrangement, again, I look at what is needed for a particular track, the number and kind of instruments needed and the final sound.

Does a track need a rhythm component? Would a standard kit be enough or superfluous? In

immersive, you need to think in terms of motion and objects. Do we need additional instruments? Do we need a horn section and string octet or something never heard before?

I’ll go back and consider the sound of a 1940s radio broadcast or a small, orchestral piece with all the instruments, not only strings. It’s all being driven by the narrative

With French artist, Sylvie Vartan, (who performed live at the Olympia with The Beatles), I tried to make a very nostalgic record with her: ‘Nouvelle Vague.’ So, we went from a very large string orchestra to a small horn section, the pop sound of the ‘60s.

I used Chamberlin on some of the tracks. I tried to use a number of retro instruments that were kind of indicative of that period, a Farfisa, and things like that. Not a lot, but just enough to make a hint of it because I didn’t want it to be a retro, like Oasis, or a Beatles type of thing.

I wasn’t trying to replicate. I was trying to pull some things forward and do new stuff, too, around these songs.

PB: Let’s talk about your collaborative relationship with Tori Amos.

JPS: With Tori and I, the same things rock us. The same classical musical eras rock us. So, when I’m listening to Tori, I understand totally; her background is my background.

We work so well together because we’re like extensions of each other. Her compositions and compositional style and what has influenced her are exactly the same as mine. The end of the Victorian era into the early 20th century: Ravel, Debussy, Stravinsky. All these modernists. All these Central European composers: Zoltan Kodaly, Bela Bartok. That’s us. It’s all about music. That’s just understood. It’s rare to have a relationship like ours.

PB: Can you define “prepared piano”and how this process affected the instrument Tori used for ‘Bells for Her’?

JPS: Prepared piano goes a number of centuries back. Preparing an instrument would be making an instrument do things that it normally doesn’t do, less so by playing, but you prepare it by actually manipulating it physically. In this case, it’s the piano—John Cage did that, other composers have done that. You can put screws between the strings and rubbers.

You can even play a regular piano with a mallet. I have a piano frame from a Lawrence electric piano I used on Willie DeVille’s record where I used a mallet on the strings on ‘Stars That Speak.’

On John Doe’s first solo record, I prepared the piano with Styrofoam blocks on the strings. Actually, it sounded a lot like an electric distorted guitar. It was actually very cool.

On ‘Bells for Her,’ we detuned the piano by two octaves and it really deranged the harmonics of the strings so they sounded much more bell-like as they got stretched. We put mutes on it so it was a mono-chord. It was basically one string stretched two octaves down and that sound, really, is evocative. It brings you to a place but you’re not exactly sure what that place is. It opened you up to her lyric.

PB: ‘Bells for Her’ has a haunting lyric and the background gives me chills.

JPS: The piano tones are diminished and the piano mechanisms noise is increased, making the sound unique.

PB: Regarding French singer Sylvie Vartan: In an interview about the album, ‘Nouvelle Vague,’ on which you arranged several numbers, she said, ‘I’m very happy with the album production and arrangements which give the songs freshness without spoiling them.’

Sylvie sings the title song, ‘Nouvelle Vague,’ which means “new wave,” with maturity and grace. Known in English as ‘Three Cool Cats,’ this Lieber and Stoller cover had been recorded by The Coasters in 1958, and by the early incarnation of The Beatles before Ringo. It was guitar-driven. Your Latin influences turned the song into a classy dance tune.

JPS: In that record, things were pretty literal. You’re drawing on the 1960s and theoretically the 60s was a very potent, emotional period, even though there was a lot of psychedelia and dancing through the flowers, with a canyon kind-of groove going on. There was a lot of hard stuff going on, especially in France in the 1960s. The youth movement had gotten to the 60s and they were rioting, like, most of the rest of the planet.

PB: Willie DeVille said, ‘He (JPS) comes up with ideas that make the sound right.’ When referring to ‘Backstreets of Desire,’ he said that you played on the wires of the Baby Grand with drumsticks, trying to find, what he felt, was that perfect sound.

JPS: I did have a Lawrence electric piano frame that I played with mallets.

PB: You produced four albums. On ‘Stars That Speak,’ Willie plays a repetitive slide guitar figure.

JPS: That was recorded at The Mayflower in New York. That song, his vocal, his speech, his slide guitar, was when I basically came in. When I left New York, we did this pre-production early on. It was in my room. We did three songs. But minimally, he would play a little guitar. Then, he’d sing or speak a little bit over his guitar. And those became the basic tracks for three songs we did over a period of the next, three decades.

PB: You added on amazing elements: the Chamberlin, for one, and started with cello.

JPS: I added live strings. Three cellos and three violas.

PB: ‘Stars That Speak’ is a wildly poetic song. You took it to a visceral level. I’m referring to the footsteps. Was your intention to have the footsteps be part of the percussive feel? Or was the point to create ambience?

JPS: Once I left New York, with Willie’s vocal and that slide guitar, basically, that’s the only thing I had. I built everything around that and moved pieces of his words around. I orchestrated underneath his narrative and it made sense.

Then, I started working on the piano frame and stuff and the melody. He’s walking as his mind is talking. So, it made total sense to put the footsteps down. Those footsteps are in an implied tempo. it’s a very natural, you know, walking tempo.

I wrote everything around Willie’s narrative, allowing him space to tell his story. I needed to parse his narratives so that it became stanzas, so to speak. Willie didn’t trust labels. Our relationship allowed him to be freestyle and maximally creative.

I considered him my brother. I respected his past. Even though we came from different backgrounds, we understood each other creatively and personally. He would often say, ‘There’s nothing as real as real.’

Article Links:-

https://www.johnphilipshenale.com/

https://www.facebook.com/johnphilipshe

Band Links:-

https://www.johnphilipshenale.com/

https://www.facebook.com/JohnPhilipShe

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Phi

Play in YouTube:-

Picture Gallery:-

Gregory Hines and JPS September 1975

Redbone with Jeff. Jack and Phil 1978