Sound

-

Interview with Bi Marshall Part 2

published: 3 /

4 /

2014

PB: How long after signing to Korova did you record ‘Jeopardy’?

BM: ‘Jeopardy’ had actually already been recorded. We had recorded it at Elephant Studios with Nick Robbins, and taken it originall

Article

PB: How long after signing to Korova did you record ‘Jeopardy’?

BM: ‘Jeopardy’ had actually already been recorded. We had recorded it at Elephant Studios with Nick Robbins, and taken it originally to Korova as a demo. The only other act signed to Korova was Echo & The Bunnymen. When we signed to Korova, the first thing that happened was that we were each given a copy of ‘Crocodiles’, which we was about to come out, and we all thought that, because that album sounds so lush and full, that we were going to be taken to a studio and allowed to re-record ‘Jeopardy'.

Greg was answerable to Rob Dickens, who was head of Warners UK, and he had just been told that their budget for that accounting period had all been used up. Korova ended up releasing ‘Jeopardy’ just as it was.

PB: Were you upset when that happened?

BM: Yeah, we were really, really upset. We knew that comparisons would be drawn with the Bunnymen who were the only other act on Korova, and who had this fantastic album with phenomenal production.

There was no budget for the artwork for ‘Jeopardy’ either. The sleeve is a Russian film poster that Greg managed to buy for £50 because it had just come off copyright. He thought that the woman with her face blanked out on it looked like me with my big glasses, and so that it was sort of appropriate (Laughs).

Spencer Rowell, a photographer friend of mine, took the photographs of us for the sleeve. He was an apprentice photographer who I had befriended in my local in Camberwell, and used to photograph food for cook books. He was quite happy to do it for free other than the cost of the film. He saw it as something else for his portfolio. In fact Spencer went on to take that famous photograph of the man holding a baby, the Athena poster of the man holding his new born baby (Spencer Rowell’s ‘Man and Baby’ was the biggest-selling photographic poster of the 1980s, and sold over five million copies – Ed). His girlfriend was a make-up artist, and she came along to the photo shoot and also did our make-up for free.

PB: How do you feel ‘Jeopardy’ stands up now?

BM: At the time I was so disappointed, but now with hindsight I can look back and I think that we succeeded in our aim which was to do an album that captures the energy of what we were like live. It just needed slightly cleaned up.

It was about that time that things started to go wrong for us. Once we signed, I think that Adrian’s attitude towards the Sound changed markedly. He started to feel the pressure delivering “the next product “as he called it, and almost overnight the Sound ceased to be fun.

PB: The Outsiders had been almost universally slated in the rock press, and it was only latterly that they started to get occasional good reviews. The Sound, however, picked up positive reactions from the critics quickly. Do you think that put further pressure on him?

BM: Possibly. Dave McCullough gave us a very good review, and we did interviews with both Paul Morley and Steve Sutherland that were quite positive.

PB: Were you involved with those interviews?

BM: Yes, Adrian’s paranoia had started to kick in quite early, and he didn’t like the fact that there was too much attention put on the only female member of the band, so he actually asked me not to speak at interviews.

At the time I thought was a little weird, but I could see that he was the front man. There weren’t many sole female members in bands at the stage. There was Tina Weymouth in Talking Heads, but that was about it. If there was one female member it tended to be the singer. I was quite happy to be just another member of the band, but I think that immediately Adrian thought that potentially we could get the wrong type of publicity if they focused too much on the only female member.

PB: You were touring a lot by that stage, weren’t you?

BM: Yes. We toured with Echo & The Bunnymen. That was the most extensive tour that we ever did. We also did a couple of short tours of Scotland, and played a few dates in support to the UK Subs.

PB: How did the dates with the UK Subs go?

BM: It was interesting (Laughs). The final night was at the Camden Music Machine in London. The audience spat at us throughout the set, which I was later told by Charlie Harper was an extremely good sign and meant they liked us. I wish they had chosen other ways though to show their appreciation (Laughs).

PB: After the Scottish dates you almost immediately did the Bunnymen tour, didn’t you?

BM: We did ‘The BBC Sessions’ before we did the dates with the Bunnymen.

PB: When was that?

BM: It was September when we recorded that session and it was October when it was broadcast. I didn’t hear it at the time and in fact until it came out on CD in 2004. We were actually on tour with the Bunnymen when it was broadcast.

PB: Those sessions are apparently recorded really quickly. Was it like that?

BM: Yes. Dale Griffin, who had been the drummer in Mott the Hoople, was the engineer. I didn’t recognise him, but Adrian did and was like, “Do you know who that is?” Then Dale promptly told us that there was to be no eating in the studio and no messing about, and we weren’t to go out at lunch and get pissed (Laughs). You don’t normally walk into a place and immediately get read the riot act. I found him quite intimidating at the time, but in fact we have stayed in contact and are now friends, and when I remind Dale of that he always says that he doesn’t remember being so difficult. The recording schedules were so tight though that if a band turned up late or messed around then he would be in trouble. He couldn’t go back to the BBC and say that he didn’t have anything. He was right to make us get straight down to work.

Again I remember him saying, “That’s amazing. You have got all the keyboard lines right on the first take,” and I was like, “Great. Can I go now?” I think my fear of him was so acute that I was just absolutely determined to get it right (Laughs).

Dale was someone who understood immediately again what the band was about without us having to explain to him. He did a fantastic job with that, and certainly on that first session, the one which I played on. I think that he captured the essence of the band. There were no trickery and no spurious sound effects.

PB: How long did the Echo & The Bunnymen tour last?

BM: It was something like twenty-one or twenty-two nights. The first nineteen were consecutive nights. I was really, really ill on that tour, and found it really, really difficult. I had strep throat, and kept having reoccurring bouts of it. Sometimes I would go out on stage and have a temperature of 102. I would be out there in my overcoat and still cold. There were probably all these people watching me thinking that I was trying to look cool in my overcoat (Laughs), but in fact I felt really unwell. We also had nowhere to sleep. We had to sleep on people’s floors and in the back of the van.

I got on fine with the Bunnymen personally, but there was a lot of antagonism there because they had been forced to take us on tour and could have had someone buy onto the tour for about eight grand, which at the time was a lot of money. Korova, however, decided that because there was no budget to promote us the easiest thing would be to put the two Korova bands on the same tour. The Bunnymen were forced to accept us, and some of the guys didn’t hit it off (Laughs).

They were fantastic with me though. They had a great tour manager, and he would take my temperature every night before I went on stage and say, “If it goes over 101, then you’re not playing,” and I would say to him, “It doesn’t matter what you say. Adrian is not going to accept it, and I am not going to want them to go on either without a keyboard player.” What they did do though was rearrange their rooms in their bed and breakfasts, so on days in which I was particularly bad I would have a bed. As far as I was concerned, they were wonderful.

PB: Echo & The Bunnymen were a huge band at the time. You would have been playing to bigger audiences than before. Was that something that the band thrived on or was it nerve-wracking?

BM: No, it is weird. The bigger the place you play the less you are aware of the audience. The lights are really on you. You can only see the first one or two rows back. I was quite nervous playing, but I found that I could fool myself into thinking that it was just the same size of venue.

Where we also really suffered on that tour was ‘Jeopardy’ had been badly distributed and was at that stage barely available outside London. We were often approached by fans while we were on the Bunnymen tour, complaining that they couldn’t get a hold of ‘Jeopardy’ anywhere. It was frustrating for everyone, and there was understandable anger from some members of the band that we were out there working hard to promote an album that was not available outside London.

PB: You didn’t appear on ‘From the Lion’s Mouth’, the second Sound album, as by that stage you had been fired and replaced by Colvin Mayers. How much did you contribute to it in terms of writing and arrangements?

BM: The Sound went into the studio within a few weeks of changing keyboard players to start recording ‘From the Lions Mouth’. All the songs had been written and arranged, and some had already been added to our current set list and played live when I was still in the band.

As far as keyboards were concerned, the only track that I had not completed was ‘Sense of Purpose’. I had problems finding my way into what the other guys were doing, so much so that they were all happy with their contributions and I was still nowhere nearly there with mine. We used to tape our rehearsals, and on that occasion I had to take the cassette home so that I could work on the keyboards in my own time. All we had on tape was me noodling about trying to find a way into that song, trying random lines one after the other. I never got to finish ‘Sense of Purpose’, and unfortunately the random noodlings stayed in, meandering all over the place, completely lost.

PB: After you were fired from the Sound, were you involved with any other bands?

BM: I played keyboards for a band called Persian Flowers for about two and a half years. While I was with them we recorded a song for a sampler album, plus just after my departure they released a single called 'Somebody Else's Sin' where the keyboards were replaced by a flute.

The vocalist was Nick Nicole, who had been in Wasted Youth. It was great to play with them at first. It was a much fuller sound than I had been used to, a rhythm guitarist as well as a lead guitarist and a front man/singer, in all a six piece band. Unfortunately they were too into drugs, and eventually the whole thing fell apart, which was depressing because a lot of work had gone into the songs and we were beginning to book gigs. I joined them before they became Persian Flowers even, and before Nick joined on vocals.

PB: Was Persian Flowers your last band?

BM: Yes. I felt pretty worn out by the music industry by that stage. I have still got my keyboard from Sound days. I just play for my own pleasure now.

PB: You went to art college and now work as a professional artist.

BM: Yes, I eventually got a place at Camberwell School of Art to do an MA in Fine Art Printmaking. It was a long road to get there, I had no qualifications in Art, only a BSc in Psychology, so I had to do everything on the strength of my portfolio.

I went to adult education classes to assemble a body of work to apply for a Foundation Course, which I then did at The London College of Printing. After that I was unsure into what field of the arts I wanted to go. I liked photography, design, and printmaking. At one point I thought I wanted to study textile design, but a short spell doing that convinced me that it was too limiting, I left to do a diploma in creative screen printing. Eventually I went to work for an arts charity, helping members of the community to realise their own projects as well as teaching and editioning prints for artists. I loved that job, as the work was so varied and I stayed there several years. During that time I also got to exhibit my own work, including some black and white photographs in an exhibition of women photographers.

I left when I was offered a place on the two year MA course at Camberwell. It seems like many life times ago that I made music with Adrian Borland. Especially as since then, my creative impulses have been channelled more towards the visual arts. I like the solitary nature of working on a project by myself in the studio, no one and nothing to rely on but myself.

PB: You re-established contact with Adrian Borland in latter years. Your partner and now husband David was his friend and had been part of the Crooked Billet crowd. Was it through him?

BM: We used to run into him occasionally at gigs. We had such similar tastes that if we went to a gig then Adrian would be there. We never lost touch completely. When you find yourself fired from a band as I was, you often not only lose everything creatively but you also lose all of your friends as well, and that is what happened to me. David and I also moved to central London, so we weren’t really going to the Billet anymore and all of that disappeared.

Adrian was always quite embarrassed when he saw me, and the Sound was never anything that we discussed. Somehow we knew that it was best not to talk about what he was up to or what I was up to. We talked about other people’s music, but not about what we were doing ourselves.

PB: He was obviously diagnosed with a schizoid-affective disorder. How aware were you of his illness in those subsequent years?

BM: We were by now seeing each other occasionally socially again. The first time that I realised how bad it was when some friends brought him over to where David and I were living, and we were due to go to an art exhibition and we took him with us. He kept talking out loud as if he was having an internal conversation. We could only hear though what he was replying. He was obsessed with a Francis Bacon painting. We had to keep looking for him as he kept wandering off, and we always found him standing by the same painting.

He had rung me a few times before then. He had been drinking heavily, and was often in his room and he claimed on his second bottle of vodka. At the time I assumed that a lot of his problems were to do with drinking and nothing more. He had never been an especially heavy drinker before then, but I can see now that the pressure that he was under with the Sound had taken its toll. I can see now with hindsight that the problems were there much earlier on.

PB: Do you think that is reflected in his lyrics? The opening track on ‘Jeopardy’, for example, is ‘I Can’t Escape Myself’, and there is the line “I hate it when I am crazy” on ‘Contact the Fact’ on ‘From the Lion’s Mouth’,

BM: I have never analysed the lyrics in that way. A lot of people now examine his lyrics with the knowledge of what happened to him later. They look for clues of his mental instability and claim that it was all there in his words.

Firstly not all the lyrics were, however, written by Adrian alone, and he collaborated initially often with Adrian Janes. Even in the band, we were not sure sometimes of who had written which lyric. Secondly, I think that the reason that the lyrics resonate so much with other people is that they express thoughts and emotions that we all have from time to time, feelings of doubt, fear, powerlessness. If the lyrics only represented the thought processes of someone with a schizoid disorder, they wouldn't mean much to other people. Over-analysis can sometimes lead to the wrong conclusions, and I think that is what has happened with Adrian’s lyrics.

All that paranoia was, however, evident from early on. At the time we used to have a saying: “Rock and roll has gone to his head.” When he would behave bizarrely, such as not letting me talk at interviews, we would all look at each other, and go, “Rock and roll has gone to his head,” and just laugh it off, but it is only with hindsight now that I can see there was always that degree of paranoia.

On the Bunnymen tour he was convinced that the Bunnymen were sabotaging our sound on stage. He was quite competitive, and saw it very much as a competition. Even if it was true you probably would go and have a polite word with the sound guys and say, “I wasn’t that happy with our sound last night. Is there anything that you can do?” Adrian, however, rang up Korova and accused the Bunnymen of sabotaging our sound. The first thing that Korova did was ring the Bunnymen’s manager, so that soured our relations between us and the Bunnymen even more.

I think all the pressure he was under made it worse. He was always quite volatile right from the first time that I met him. I think of him now as victim of rock and roll. If people see you as being creative, then they allow you to behave in a way that they wouldn’t accept from someone else. If he had been working in any other field, then it would have probably been picked up a lot sooner.

PB: Do it come as a shock to you when he died?

BM: It did. Although I knew latterly of his illness, I don’t think that I had ever realised how serious it was. I knew they he had attempted to try to kill himself before, but those suicide attempts had seemed almost kind of half-hearted, like jumping in front of a car with his guitar.

I thought that now that as he had been diagnosed with a schizoid-affective disorder and that people knew there was a problem it would be under control. He had, however, told me that he sometimes used to not take his medication. He felt that it stifled his creativity. He just couldn’t stay on his medication because being creative was so important to him and it numbed that. It was not taking that which eventually led to his death.

PB: Are you surprised at how well remembered the Sound are?

BM: I am so surprised by the interest that still exists in the Sound and Adrian's other projects. I am pleased for him, and the others such as Pete Williams that are also sadly no longer with us, that their work has not been forgotten.

PB: What are your happiest memories of being in the Outsiders and the Sound?

BM: Going on stage for the first time with the Outsiders was definitely one, and hearing a lot of Adrian's friends panicking, asking him if he was sure about putting a female clarinet player on stage with a punk band. Pete was the most vocal. He really thought it would be a disaster and we'd probably get bottled off stage. Ironically he later wanted me to come and play with the Crazies.

Recording with the Crazies was by far my happiest day. There was no pressure. It was just a fun day out with friends making music.

Being in the recording studio was always happy. We were lucky to work with people who understood what we wanted. Nick Robbins at Elephant Studios was a dream to work with, as was Dale at the BBC. We didn't have to try and explain what we were about and how we wanted to sound. They just got us. They knew instinctively what we wanted. Recording was always straightforward, fast, no timewasting.

PB: It seems that in hindsight all your happiest memories are of the earliest days of working with Adrian.

BM: You are right. All my happiest memories are of the early days, hanging out and making music with friends, being encouraged to contribute ideas - the wilder, the better. Talking music with mates, even arguing passionately about it. Going to gigs together. Once Adrian Janes left to go to university, everything changed. The dynamic within the band was altered forever, and signing to Korova brought yet more changes. Had we been as strong and as united as we'd been in the old days, we might have fared better.

PB: Thank you.

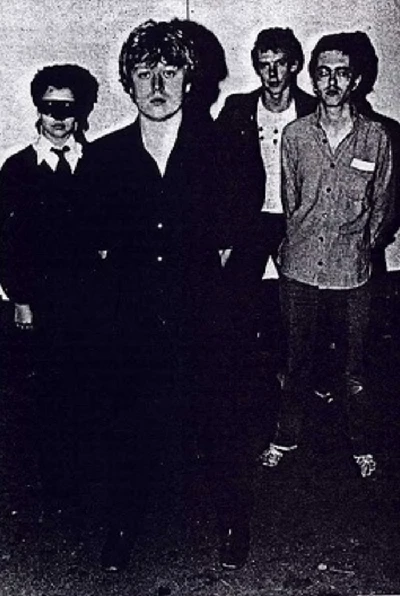

Thank you to Rients Bootsma at the Adrian Borland and the Sound website Brittle Heaven www.brittlehaven.com who provided the photographs that accompany this article.

Article Links:-

http://www.brittlehaven.com

Band Links:-

http://www.brittlehaven.com

Picture Gallery:-