published: 9 /

6 /

2021

Bob Nicholson reflects on the parallels and contrasts between the careers of original rock and rollers Cliff Richard and Elvis Presley.

Article

Two singers, two originators, were at the beginning of rock and roll and stayed the course to enjoy careers at or near the top of their profession all their working lives. One was Elvis Presley, the other Cliff Richard.

Elvis was the original, a beneficiary of a fusion of musical styles he grew up with and the serendipity of timing that placed him, his physicality and his voice before the teen public when they were demanding something, some musical style, for themselves.

Cliff Richard was inspired by Elvis and other US rock and rollers yet became an original himself along with his backing group The Drifters (renamed The Shadows) in developing their own unique musical sound that came to inspire others too.

In the UK and around the world, with the exception of the USA, the media started to write about Elvis v Cliff. Over the next twenty years, their careers would run in parallel. Elvis had the upper hand at the outset. Who had the better of the competition by the end? Did Cliff pass his inspiration as a performer, a creative force and a recording artist?

Opinions, arguments, theories differ still over when rock and roll was born, who had the first rock and roll record, who popularised it more than most. Elvis Presley came to be the anointed King of Rock and Roll though he was not the first on the scene. When he recorded ‘That’s Alright’ in Sam Phillips’ studio in Memphis in July 1954, Bill Haley had a US top twenty entry with ‘Shake, Rattle and Roll’ just two months later and a US Number One in the summer of 1955 with ‘Rock Around The Clock.’

Chuck Berry had a US Top Twenty hit in 1954 with ‘Maybelline.’ Elvis’ breakthrough single nationally in April 1956, ‘Heartbreak Hotel,’ was followed into the US top ten by Carl Perkins’ version of his own song ‘Blue Suede Shoes.’

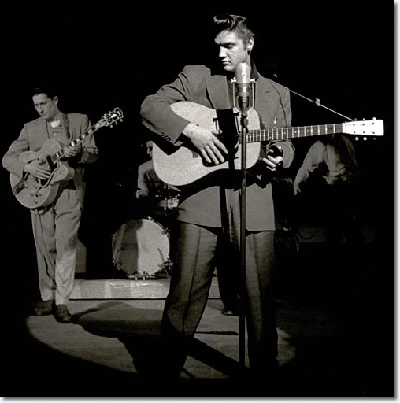

Little Richard‘s ‘Long Tall Sally’ charted at the same time. What separated Elvis from his competition was his voice, his looks and his stage presence, a sexual display that shocked the media and delighted the young female public. None of his competitors rocked in quite the same way.

Elvis’s success in the US was followed in the UK, inevitably, given the dominance of the US in popular music hitherto. As he has said many times, Cliff Richard first heard Elvis singing ‘Heartbreak Hotel’ on the radio of a car parked briefly outside a newsagent in Waltham Cross, London. A search of the American Forces Network (AFN) in Germany found the song and the singer.

Elvis, in general, and rock and roll, in particular, became Cliff’s passion. Through AFN and Radio Luxembourg, he and other British teenage rock aspirants became familiar with the growing number of US rock and rollers and their music. Around the time Elvis was being inducted into the US Army in 1958, Cliff was forming his own group and playing his first date as Cliff Richard and The Drifters (renamed The Shadows a few months later) in Ripley, Derbyshire. Cliff was at Number Two in the UK singles chart with ‘Move It,’ widely regarded as the UK’s first proper rock and roll single, as Elvis arrived in Frankfurt for the start of his two-year army posting.

Elvis’s manager, Tom Parker, decided that Elvis would not record whilst he was in Germany, obliging RCA to release older material linked to his earlier movies. They still made money with minimal effort. There were only six single releases during those two years, of which two reached Number One.

Cliff and The Shadows were able to fill the British void and develop their style, becoming adopted by the media as the country’s answer to the US. The group had three Number Ones from twelve releases and two hit albums with The Shadows separately having their first number one, ‘Apache,’ as an instrumental group.

In the press, it was now Cliff and Elvis, Elvis and Cliff in the UK and increasingly around the world. Although Cliff and The Shadows toured the US as part of a package, they didn’t get the backing from the record company necessary to break through. The US music business had their teen acts like Ricky Nelson; so why back a Brit? It was another five years before such protectionism was blasted aside by The Beatles.

By the beginning of the Sixties, Cliff was catching his inspiration. Elvis’s absence from recording or performance meant he hadn’t moved forward. When he did return, in the summer of 1960, it was as a movie actor, not a rock and roller.

Cliff and The Shadows had improved dramatically in those two years. It is important to realise that they were a group, not a singer and his backing band. Whilst the PR focused on Cliff, the music they made was that of a cohesive whole in a way that was unusual at the time. The Shadows were more important to Cliff than Scotty Moore, Bill Black and DJ Fontana were to Elvis. The latter were players, doing what the record company producers considered sold. There was no innovation driven by them.

In contrast, The Shadows were crucial to Cliff’s development, as was Cliff’s purchase of the first Fender Stratocaster to be imported into the UK. They created a unique sound which Cliff fronted, wrote songs for him and participated in stage routines, emphasising the group as a unit.

The release of ‘Me and My Shadows’ in October 1960 preceded by two months Elvis’s first offering post-Army, the soundtrack to the film, ‘GI Blues.’ These two albums set the scene for what was to come in their respective careers. Sales are a primary indicator of popularity but they are not always a reflection of the quality of the music or the progress of the artist. A product-starved Elvis public sent ‘GI Blues’ to the top of the album charts at Christmas 1960. ‘Me and My Shadows’ was held from the top by the ‘South Pacific’ soundtrack a month earlier.

However, here was an indicator of Cliff’s competitive nature and determination to develop, compared to Elvis’s willingness to fall in with Tom Parker’s strategy to allow fans to see him on film after lucrative film. Music was less important to Elvis than being a movie star.

Cliff and Elvis would continue to dominate the UK charts over the next three years. It’s a subjective judgement as to who had the better of it. It’s fair to say, however, that after the classic (‘Marie’s The Name) His Latest Flame’ (1961), Elvis dropped rock and roll for big ballads and mainstream pop.

Cliff and The Shadows maintained their love of the music whilst broadening their repertoire, a rock and roll song always on a ballad B side (‘Willie and The Hand Jive,’ ‘Do You Wanna Dance’). Indeed, one of Cliff’s 1962 hits was a cover of Jerry Lee Lewis’s ‘It’ll Be Me.’

Another comparison for this period is in the films in which the pair starred. While the Hollywood production line gave his audience Elvis in ‘Girls, Girls, Girls,’ ‘Blue Hawaii,’ and ‘It Happened At the World’s Fair,’ Cliff starred in ‘The Young Ones’ and ‘Summer Holiday,’ both of which were second at the UK box office behind Bond films. In addition, Cliff and The Shadows were touring the world, their reward for which was Billboard’s announcement that the top World Recording Artists in 1963 were Cliff first, Elvis second and The Shadows third.

By summer 1963 the public mood was ready for change. A pop/rock volcano erupted in the form of The Beatles, swiftly followed by a tidal flow of new groups, first from the UK and then the US. Elvis and Cliff were no longer top of the pops. What was happening in the UK proved irresistible to the US market in a way it never had before. The US industry couldn’t ignore the Beatles. Both Cliff and Elvis topped the UK charts in the first months of 1963 with singles and the soundtrack albums from their films.

However, The Beatles captured the changing mood, dominating the charts around the world and drawing other new pop groups into the market in their wake. Elvis and Cliff faced increased competition. They remained in the charts but less often at the very top. Elvis had one Number One in the mid-Sixties, ‘Crying in the Chapel, a gospel number recorded by him in 1960. Cliff had two Number Ones, ‘The Minute You’re Gone’ (1965), recorded in Nashville, and ‘Congratulations’ (1968) the UK’s Eurovision entry.

Both artists had a loyal fan base and additionally were held in affection by a wider audience. Their careers might be said to plateau during this period whilst still charting and remaining in the public eye. Elvis’s movie-making continued without enabling him to break through as a serious actor, restricted to roles where he was a singing centre-piece.

Cliff’s stage work with The Shadows continued including two London pantomimes that The Shadows scored. Cliff was always a competitive person. He wasn’t one to accept second place without a fight. Consequently, he sought a wider range of writers for his recordings including Neil Diamond and Jagger/Richards. Elvis continued turning out music soundtracks and showing little in the way of a response to the British invasion or the arrival of US bands like The Beach Boys.

It’s interesting to note that both Elvis and Cliff recorded gospel music during the mid-Sixties. Cliff was a Christian convert during this period after searching for something more meaningful in his life than pop stardom.

Elvis was brought up as Christian in Memphis with the South’s particular infusion of soulful gospel music. Both recorded gospel albums in this period. Cliff, the convert, threw himself into it after briefly considering retiring.

Elvis’s upbringing meant gospel music was ingrained with the advantage that gospel music had its own commercial market and charts. Cliff found gospel a new form of music with which to express himself. He made a couple of films for a Christian audience and toured with other Christians in a small way, quite different from his usual concerts, raising money for charities in the UK and Europe. It was in this period, in the late Sixties, that he was introduced to the TEAR Fund charity which he would support over many years.

The careers of these two pioneers were exceptional, not only for their music but for their longevity too. There were few artists who were in at the beginning of the new music and stayed the course at the top. Short, but fruitful, careers were the norm for the early rockers as they diversified or were content to work regularly at a lower level. Elvis and Cliff were, unknown to them, running a marathon. By 1968, they were approaching halfway. Elvis had an early lead for two years but dropped his pace. Cliff started later but soon caught his inspiration. Crowds of runners overtook them after the seven mile mark (1963) but the two continued running, gaining footholds again as others faltered, as pop/rock diversified into different genres (heavy metal, acid rock, punk et al). Their core fans urged them on.

1968 proved a pivotal year. Both artists coasted through the middle Sixties, continuing to be successful and maintaining their profiles. Elvis had his films; Cliff toured and had BBC TV series. Eventually, though, the need for more and better became pressing. In Elvis’s case, his need for action was financial. Parker took half of Elvis’s earnings added to which Elvis was free-spending. His movies were no longer making money and Hollywood showed no inclination to make him into a Brando. He had to return to performance. His absence from the stage had created a demand which Parker was intent on satisfying, at the right price. The outcome was the 1968 NBC TV Special, brilliantly produced by a young director who had a clear vision of how to present his star, quite different from Parker’s perception. Elvis rocked in front of a thirty-piece orchestra and backing singers formed from two soul groups and revived his career as the global audience welcomed him back. The 1968 TV Show was a huge boost to Elvis’s confidence. He had given up singing to live audiences for more than ten years. Paradoxically, that absence was to benefit the return strategy by making the Elvis public hungry. He had affirmation that he could still perform live and capture an audience. The following year, two good songs, ‘In the Ghetto’ and ‘Suspicious Minds’ took him back into the US top ten.

Parker booked him into Las Vegas, where he would perform a couple of seasons for the next eight years until his death. Lake Tahoe also featured. Punishing tour schedules around those dates were arranged for those years, too, but only in the US. Elvis had ceased to be a rock and roller a decade previously.

Now he was an icon, ideal for Las Vegas, backed by a huge orchestra, theatrical staging and delivering a strong back catalogue that the fans wanted to hear. The tour dates were borrowed from the Las Vegas shows. His powerful voice had held up well at first, rich, deep, immediately recognisable, still tingling the spine for the fans.

It is a moot point, however, as to whether these shows represented progress. He stayed in the USA when the fans in the rest of the world were waiting, wishing and watching. There seemed to be no advance, no renaissance, reinvention or improvement beyond his base. Just Elvis, doing what Elvis did with a musical multitude behind him.

Elvis’s absence from touring and his failure to work overseas was bound to impact on his progress. Elton John (Guardian article, 9th February 2021) commented on the importance of touring:

“We played on the Reeperbahn, five hours a night... to audiences who hadn’t come to see us. But it was still great: we played so much we didn’t have any choice but to improve as a band...... “

“Getting your music across to crowds from a different culture to your own, who don’t necessarily speak the same language as you, just makes you a better musician...... you can spend months in a rehearsal room painstakingly perfecting your craft and you won’t learn as much about live performance as you do in half-an- hour trying to win over an unfamiliar audience. You have to have that visual contact with other human beings. Touring Europe allows you to absorb different influences, understand different crowds, meet new musicians. It helps you get inside your art.”

Around the same time as Elvis was making his comeback, 1968/69, Cliff was drifting commercially. He had devoted a considerable amount of time to his Christian work which left him coasting on the commercial side. He needed impetus too. That same year, he accepted the challenge of representing the UK at Eurovision, a show viewed across Europe by millions. Coming second did him no harm and gave him a Number One across Europe including the UK. The contentment he had found with his religion, and the gospel work around it, seemed to have settled him. He had continued working with his long-time producer, Norrie Paramor, who usually found his material for recording. Columbia released three or four Cliff (with or without The Shadows) singles a year throughout the Sixties and into the early Seventies. These included the self-written ‘I’ll Love You Forever Today’ (1968) and included two early environmental songs, ‘The Joy of Living (1970), a satire on road building, and ‘Silvery Rain’ (1971) concerning crop dusting. Both songs were written by Hank Marvin, who is also credited alongside Cliff on ‘Throw Down a Line’ (1969), an earthy song with a very different sound to that usually associated with Cliff.

Overall, however, the lack of a studio album for four years and only charting for the most part at the bottom end of the top thirty indicated some rust in the machine. It was time for a change which the 1972 retirement of Norrie Paramor enabled. David Mackay took over to play a crucial role in the Cliff renaissance that was to come.

A second Eurovision representation for the UK led to a top ten hit for Cliff (‘Power to All Our Friends’, 1973). Mackay then introduced a new recording regime with Cliff working in the studio with four young Australian musicians. He encouraged Cliff to write songs, four of which were included in a singer/songwriter type album called ‘The 31st of February Street.’ Cliff fans were unenthused but the singer wasn’t, he felt it was a rebirth. After a blank year on the singles chart, a pivotal decision was made by Cliff’s management to change producers. The first person to compile the best selection of songs could have the gig; it was Bruce Welch. Working with top musicians under the perfectionist ears of Welch led to what was regarded, even by the serious music press, as Cliff’s renaissance. The album ‘I’m Nearly Famous’ became a top ten hit in the UK, providing Cliff with hit singles including ‘Devil Woman’ which made the top ten in the UK and the US in 1976.

The change of producer led to Cliff being more adventurous in his vocal delivery. Cliff’s wasn’t a power voice in the way that Elvis’s was, but its tone was distinctive and appealing. He was able to deliver a range of song styles from rock and roll to sensitive ballads. ‘Miss You Nights’ and ‘Devil Woman’ on the same album illustrated the diversity of his output induced by Welch. Harmony had always featured in his work with The Shadows. The new regime enhanced it as an important feature. The Aussies he had recorded with formed the nucleus of a new band supported by a vocal backing group led by Tony Rivers to deliver the harmonies that featured extensively in his performance. They would be his band for the next decade.

As Cliff began the upward curve that would re-launch him as a top performer globally, Elvis was in decline and feeling the pressure. His drug dependency is said to have started in the army but accelerated in the late Sixties. Addicted to prescription drugs that set him up to perform then brought him down to aid sleep, he was struggling but working at an unremitting pace that brought in the money.

He was pushed hard in the Seventies carrying out an estimated six-hundred nights of performance, occasionally two shows a night, albeit only an hour long. His extensive touring and Las Vegas residencies were mentally and physically exhausting.

Being Elvis was a massive pressure in itself, with expectations raised among the faithful for the man with the reputation as the King of Rock and Roll. His last top ten hit in the US and the UK was ‘Burning Love’ in 1972.

RCA were ruthless in their demands, issuing repackaged material in album form and re-releasing singles to exploit his talent and in doing so overselling him. There was no space for innovation, even if he wanted it. By 1976 he was burnt out, in bad physical shape and still on the road. Cliff was in Russia, the first pop/rock star to tour the country. In this same period, Cliff worked just over half the number of nights that Elvis did. Having run alongside each other for sixteen years, their career paths had now crossed. In marathon terms, Cliff took the lead as a sickly Elvis fell back.

Significant responsibility for the different outcomes of the two careers rested in their management. Much has been written about Tom Parker who managed or, perhaps more accurately, controlled Elvis from 1956 to his death in 1977. He had no other artists to manage. Parker viewed Elvis as an asset to be exploited. His health and wellbeing did not seem to be a consideration. In addition, Elvis was living in a sort of bubble with his Memphis boys, all of whom were dependent on him financially and thus not best able to challenge him on his lifestyle or his drug dependency.

These personal circumstances were very likely to impact on his work. Cliff was more fortunate. Peter Gormley was a manager in stark contrast to Parker. Described by Cliff as quiet, polite, shrewd and friendly, he was already managing The Shadows and another fellow Australian, Frank Field. He took over managing Cliff in 1961 and stayed with him for the next twenty five years. He took no fees from work already contracted. He seems to have been a friend and a father figure dispensing guidance as well as a manager doing deals. Additional support came from road manager David Bryce. Cliff had a wide circle of friends, many outside show business. His charity work was extensive which made him widely popular in the industry and helped to keep him grounded in a way that was not available to Elvis in the latter’s circumstances.

The decade up to Elvis’ death in 1977 reveals considerable divergence between the two pop/rock innovators. Whatever difficulties his private life caused him, professionally Elvis was still, in the reporting of the media and the minds of the public, the King. His rebirth through the TV concerts and his early Las Vegas shows reaffirmed his position. What is remarkable about the two standout performances heralded by the critics, the 1968 TV special and the Hawaii concert, is that there were, in fact, only two over those seventeen post army years. In effect both received global coverage because of their rarity value. The myth held up. His work didn’t suggest that he was looking to compete against contemporaries. Elvis carried on being Elvis, relying on his reputation to keep him hailed as ‘the King’, albeit not a soubriquet he personally endorsed.

By contrast, Cliff had always been competitive. He adapted to changing fashions in hair styles and clothing but subtly, choosing smartness whilst others went full hippy (the Cliff quiff survived a couple of years before following the trend to a fringe). He didn’t enjoy being displaced by The Beatles, indeed seemed irritated by them, praising other new groups in the revitalised pop/rock music business instead. As an established artist, he didn’t have the benefit of being new so was unable to take advantage of the US being opened up to British music. Instead, he built on his international standing by touring constantly overseas with The Shadows in their different guises (including Marvin Welch and Farrar) and as individuals.

Always visible on TV and on tour, he retained the affection of the public by a high work ethic, his accessibility and his wholesome character. As Elvis treaded water, Cliff’s competitive nature put him back in the flow, becoming a risk taker where Elvis wasn’t. By 1973 he was prepared to try new material and face down the views of the music critics. In the same year, as his health was failing, Elvis seemed content to live on his reputation despite the pressure he felt from it.

Elvis’s decline can be traced back to 1958 and his induction into the US Army. The conundrum is why Elvis allowed it to happen. Was it a lack of self confidence on his part? He had two years of adulation as a rock and roll innovator then two years kicking his heels in Germany. When he returned, the rock/pop business had grown. Was filmmaking simply too easy?

It is recorded that he wanted to be a movie star yet he must have realised soon enough that the musicals weren’t going to make it happen. Was he complacent? The most perplexing question is why Elvis didn’t part with the man who was taking half his earnings, showed little concern for his health and well-being and prevented him from moving forwards with his stage performances and his choice of material.

Elvis didn’t tour outside the comfort of the USA when he would surely have revived his career and earned vast sums. Why not? The proffered defence is that Parker may have been an illegal immigrant of Dutch origin without a passport. He couldn’t risk going abroad. Yet it was entirely feasible for a road manager to be appointed to look after his artist on tour. Either Elvis was too weak to challenge Parker or he didn’t care enough about the direction of his career.

There is little indication that Elvis spent much time crafting his work in the recording studio. His disinterest in the music from the films usually meant he would do a couple of takes. The rebirth briefly led to a resurgence of interest in a Memphis recording studio when he cut ‘In the Ghetto’ and ‘Suspicious Minds’ amongst others. Sadly, his interest didn’t last long. As his health deteriorated he spent less time perfecting his studio work. Elvis determined the success of any session depending on his mood and engagement. Cliff had been through the same phase of voice over recording to base tracks but his revived interest with Mackay led to him once again working with the musicians in the studio. He always put himself in the hands of the producer and the musicians. Cliff has said many times that recording was his greatest love. (Beyond the period under discussion here, he went on to produce much of his studio work himself as well as help out his gospel friends.) The improvement in the quality of the output was demonstrable. He became an album artist without yielding his interest in the singles market.

If it is possible to be objective in a subjective medium like the arts, how did the two compare over their marathon run? As the Elton John quote above noted, musicians and singers need to play live to audiences if they are to improve. Elvis’s absence from live performance for ten years meant that he had a heavy reliance on his history, his back catalogue and his reputation when he resumed live shows. Elvis--as the fans remembered with nothing new to offer. Twenty or so songs, a few in medley form. Some dramatic theatre was also deemed necessary as his audience was to be the middle-aged middle classes in a top Las Vegas hotel prepared to stump up the ticket price for dinner and Elvis. The spectacle became as important as the artist leading to Elvis becoming a clothes horse for his bejewelled costumes and cloaks. This show was taken on the road for the next six years to towns and cities throughout the US. Sadly, the Elvis motif now is represented by a white jumpsuit rather than the gold lame of his wonder years.

Cliff adopted no such straitjacket. Working every year since 1958 on commercial and gospel tours and frequent television, he was very comfortable with live performance. By 1972, he was carrying two hour shows himself without support featuring more than thirty songs. His experience meant that he knew how to hold an audience and build a performance. When he had a new album to promote, the set would be a mixture of hits and the new songs. The recording changes introduced by David Mackay, then Bruce Welch, impacted on stage performances too. Cliff was a competent guitarist and would accompany himself on solo spots. The excitement brought about by ‘I’m Nearly Famous’ and songs like ‘Devil Woman’ provided opportunity for imaginative stage presentation. He used a regular lighting and sound crew and was amongst the first to use laser techniques in lighting. Cliff was every bit the showman as Elvis but his approach was more subtle than the dramatic theatre of his rival. The Cliff renaissance contrasts with the Elvis rebirth, the former about progressing, being contemporary and challenging his peers and the latter about consolidation and exploitation of an illustrious past.

Did Cliff Richard transcend his first idol, Elvis Presley? What criteria could be used to argue the case? Basically, it has to be about the work presented to the public. Whilst that is a qualitative, subjective judgement, what goes into that work is measurable to some degree. It is this writer’s view that Cliff overtook Elvis as a creative force around 1973. Both had two years at the beginning of their careers when they were pioneers in their own way. After that early thrust, they settled into their separate approaches until disrupted by The Beatles and the beat boom. Eventually their respective awakenings, Elvis for financial reasons, Cliff as a perpetual competitor, brought them to the fire again. Elvis firmed up his base and exploited his history; Cliff progressed with new material, a new band and expanded his vocal styles. As Elvis toured his nostalgia show, Cliff toured to promote ‘I’m Nearly Famous’ and ‘Every Face Tells A Story.’ He would go on to another chapter in his long career. The Elvis myth would be protected to enrich those still holding his assets long after his death.

Band Links:-

https://www.cliffrichard.org/

https://www.facebook.com/sircliffricha

https://twitter.com/SirCliffNews

Play in YouTube:-

Picture Gallery:-

Visitor Comments:-

|

|

960 Posted By: Bob Nicholson, Cheshire on 16 Jun 2021 |

Correction: Maybelline was a hit in 1955, not 1954. Apologies.

|