published: 8 /

12 /

2014

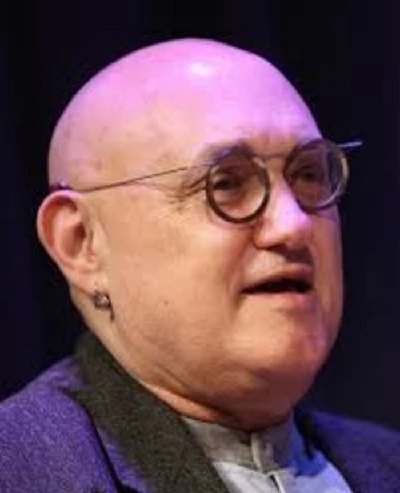

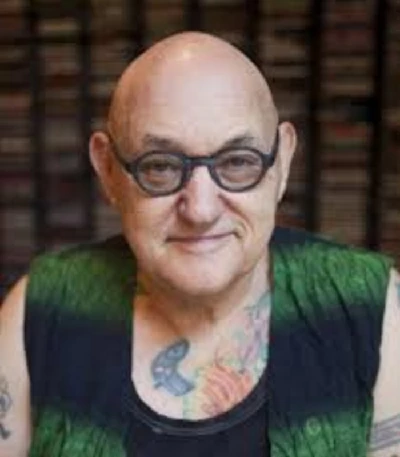

Lisa Torem speaks to ghost writer and music biographer David Ritz about his writing career upon which he has collaborated with Aretha Franklin, Ray Charles and most recently Aerosmith's Joe Perry

Article

Having worked with hundreds of subjects and not always under ideal conditions, David Ritz has mastered the art of getting to the heart of the matter. Once he sniffs out a story, he brings it home, fries it up and lays it on the community table and that’s why we keep coming back for more. You just can’t get more intimate than that.

He’s versatile, tenacious and completely strung out on the concept of co-crafting authentic stories. Originally from the East Coast, but now a native of Los Angeles, David Ritz is one of the most talented and prolific American writers ever.

David has written thirty-six collaborative autobiographies and has recently published the long-awaited ‘Respect: The Life of Aretha Franklin’. He won a Grammy for Best Album Notes for Aretha Franklin’s ‘Queen of Soul—The Atlantic Recordings’. He has written more than a hundred liner notes, and has been a multiple winner of the coveted Ralph J. Gleason Award. Over the past few years, he has co- written novels, ‘Power and Beauty’ and the sequel ‘Trouble and Triumph’ with rapper T.I. This series is but one of many imaginative novels penned.

2014’s ‘Rocks: My Life In and Out of Aerosmith’ with Joe Perry quickly shot up the ‘New York Times’ bestsellers list. It’s so much more than the traditional rock biopic. Way before Joe discloses his visceral account of life on the road, he exalts in his simple, rustic surroundings. ‘Rocks’ slows down the pace of life to reveal the beauty of an artist’s soul.

David’s open-ended passion for music means he has always been on the lookout for contrasting perspectives. He’s worked with classic songwriters, Leiber and Stoller, balladeer Jimmy Scott and producer Jerry Wexler. Like Joe Perry, he’s been afflicted with an incurable appetite for American blues; perhaps that’s what drew him to collaborate with B.B.King on ‘Blues All Around Me’ at the end of the 1990s.

In interview with Pennyblackmusic, David Ritz explored the joys of ghostwriting and discussed the high points and challenges of his amazing career.

PB: You were in advertising prior to writing the ‘Brother Ray’ book, weren’t you, David?

DR: I was. Nobody has asked me that.

PB: Advertising often requires condensing information but writing Ray’s book meant creating the big picture.

DR: I did it actually because advertising was a short form and it frustrated me, and I wanted to expand and extrapolate and stretch out. I also got tired of saying good things about merchandise that I didn’t quite believe in and advertising is tough because it’s so hard to get clients, and when you get them you have to make them happy and you don’t have a lot of choice. Also, I never got to write about music, which is my first love.

But I’m very grateful to advertising. It taught me how to deal with a client, and as a ghostwriter you always have clients and it taught me how to turn the material in on time and you can tell me, “Give me two thousand words,” and I know how to do that because I was trained to do that as an advertising guy.

Advertising and college were the two most important influences on me. Studying literature in college was extremely helpful. It showed me who the greats were and taught me some critical acumen, which I think everybody needs. Then once I quit advertising I still wanted to make a living, and advertising taught me how to make a living by turning in your material on time and making sure that it had a certain sparkle to it.

PB: You initially sent a Braille message to communicate with Ray Charles. When he agreed to work with you, did you know what you were getting into?

DR: No, I had no idea what I was doing. I didn’t even know what ghostwriting was because when I went to college I had learned about biographers, but they don’t teach you about ghostwriting and so I presumed I was just going to do a biography of Ray. My agent, however, told me that people would be more interested in hearing a book written in his own voice, and I still refused and said, “No, I’d rather do a biography.” Then my agent asked me the question,”Which book would you rather read, a book written by an egghead intellectual in his voice or a book written in Ray Charles’ voice?” and I said I’d much rather read a book in his voice. Then he said, “You should really write the book that you want to read not the one that you believe you should write.”

PB: That was good advice.

DR: That was good advice, and then when I got into it, I still didn’t know what I was doing. He would talk and I would tape and then I would type up the transcription, and if you type up a literal transcription that still isn’t the voice. I mean, the eye hears differently than the ear, so to create a voice on the page is a work of art and I don’t mean high art but it’s artifice. It’s art in that it’s artificial, so you have to create the illusion that Ray Charles is talking to you and you cannot create that illusion by simply typing the transcript. You have all sorts of choices to make and in order to duplicate or to replicate or approximate the rhythm of a real person’s talk and give a flavour of them--that requires an artistry, which I had but I didn’t really know I had.

PB: So what became the formula after that epiphany?

DR: The formula that I ultimately discovered was with jazz, which I’ve always understood intuitively, With jazz musicians every song is composed of chord changes, and in jazz you improvise upon those chord changes. The chord changes provide you a guide to your improvisation and so what I realized my formula was, was the transcripts, which was the information given to me by Ray Charles, it was the chord changes and I could improvise upon those. I could create a dialogue, a conversation between him and his mom. I could do all sorts of things - I had all the tools available to me that any writer has whether he’s writing novels…and to this day I’m an improviser. I don’t really outline. It’s hard for me to outline. I want to feel as though I’m playing my keyboard as an instrument and I hope that doesn’t sound pretentious.

PB: No, not at all.

DR: But it’s really true and I’m extremely prolific, not because I’m any kind of genius but because I enjoy doing what I do so much. Piano players are always playing and that’s how I look at my work--not as something that has to be written in stone. It’s an improvisation and it’s having fun.

PB: You collaborated with Marvin Gaye, but unfortunately, he wasn’t around to help you finish ‘Divided Soul: The Life of Marvin Gaye’.

DR: That was hard because I loved him so much and the only comfort I had in that was that I had all of these interviews with him so that a lot of the book is written in his voice, but I had to be the storyteller because he wasn’t there to approve what he had told me and the book,

Even doing that book, which was really well-received, it still didn’t make me really want to be a biographer because I was still enamoured with the ghostwriting process and so, after Marvin, what I did with the Neville Brothers and Smokey Robinson and Etta James and B.B.King, I kept on doing ghostwritten books mainly because I was challenged by the form and I really liked the form more than a biography. Even to this day after having done Aretha’s book, which is a biography, I immediately went back to doing autobiographies.

PB: Being a writer can be an isolating experience. A lot of writers would attest to that, so being a collaborator sounds exciting. Has that been an important factor?

DR: That’s a huge part of it - -that I’m a people kind of person. I like people, I like to interact with people and I like to get to know people, and I like the interviewing process; being sort of a dime store psychotherapist, which you inevitably become and I like it. I’ve had tons of psychotherapy myself and I’ve always liked the process. I like it as both a patient, and I like it as a jive ass imitator but intimacy, to me, is an exciting thing and the interviewing process is all about intimacy. If you can get intimate with people and get them to speak intimately to you, then you can write an intimate book and I think intimacy is what we’re all interested in as people.

We all have superficial encounters and they’re okay because they’re all part of life, but it’s those encounters where you open your heart and have people really listen to you and care about you. Those are the things that I think we hunger for.

PB: Critic Lester Bangs believed that there’s a wall between the journalist and subject. Do you think

that’s true?

DR: I don’t. I know his work well and I have a lot of respect for him as a critic but I just went another way. I’m not a critic. I’m a ghostwriter and that’s different. Of course, when you’re a biographer you become a critic and maybe that’s why I don’t love it inordinately, but I much prefer to be the nonjudgmental ghostwriter.

PB: You spent two years on the road with Etta James when writing ‘Rage to Survive’. That’s quite an investment of time.

DR: Every artist is different. There are other artists who will give you cuts and trade in a month where you can go over to their house for two or three hours and do it all in a month, but Etta was pretty distracted. You had to catch her when you could and you’d go on the road and maybe in two weeks time you might get two hours with her,

PB: I was looking through ‘Brother Ray’, ‘When I Left Home’, and ‘Rocks’, and one thing that I found impressive was that you bring out very strong character references in those early pages. They don’t hit you in the face—they’re very subtle and very telling—but they’re couched in a really poetic way. For example, in the ‘Flour Sack’ chapter in ‘When I Left Home’, young Buddy Guy exclaims that in spite of being a poor sharecropper: “I was happy being out there with my daddy.” When you first get together with your subjects, how do you get them to discuss these early years so candidly? It must take a while to achieve that level of trust.

DR: Actually, I’m a believer that if you can get the childhood right it’s easier to understand the rest so I spend a lot of time on mommy and daddy on the first eight or nine years of their lives. It’s a common understanding that that’s where our character is born. If I can get as many details as I can about what happened in those pre-teen years,

I feel like I’ve begun to understand the person, so I really try hard to work chronologically. I learned a lot doing Ray’s book. I remember once, we were in his childhood, and he started talking about something that happened when he was nineteen. I gently said, ”‘Ray, we’re not there yet,” and he looked at me and told me, “Well, you’d better get me while I’m hot on this’,” so I quickly dropped my expectations and I did what he told me to do and I’ve always tried to do that so if a person is hot talking about a certain thing at a certain time, you’ve got to go, but usually you have a good chance of guiding the conversation and when I do, I spend really lots and lots of time in childhood and look for key character building moments.

PB: You had already worked with Aretha Franklin at the end of the 1990s with ‘From These Roots’. You have, however, recently published “Respect: The Life of Aretha Franklin’. You’ve gone full circle. Why? Did you feel her story still hadn’t been told?

DR: I have never had eyes to be a biographer once I learned the joys of autobiography, but in every book I’ve written, I’ve always felt as though I got the story. They’re not perfect books and other people will come back and do other books on these people, which is great - we’re all here to help each other, but in Aretha’s case, I knew there was a better story than she was willing to tell.

I chased her from 1976 or so until she called me that day in Detroit in the mid 90s, so I was chasing her for eighteen years, and writing her postcards and letters and saying, “I have to write your book,” and once I got the gig I was so excited. It was one of the highlights of my life to be able to do the autobiography of Aretha Franklin. So, I had all of these expectations and I enjoyed getting to know her and we had some good times together listening to music, but I couldn’t get her to ever pull up the shade; the shade was always down and we did the book we did, and again it’s my job and the star always has control of the book and everything—you have to live with that notion.

The book came out and years went by, and also while I was chasing her I had done gobs of interviews with people in her life because my idea was that when I would get to meet her I would present myself as the world’s living expert on Aretha Franklin and tell her, “I’ve talked to your brothers and sisters, your producers,” and when she looked at the huge amount of information, she didn’t want to regard any of it.

She said, “I’m not interested in any of that. Here’s my story and I’m just going to tell it to you,” so all of these interviews that I had done were never applied to that book, so I was sitting on a goldmine of interviews which had no relevance at all to the book I did with her--at least in her mind they had no relevance--and they never became a part of that book.

I had done a book with Jerry Wexler, her producer, and I had done one with Smokey Robinson, one of her closest friends growing up and I had spent an enormous amount of time in Detroit because of the Marvin Gaye book, and I had done all these interviews with Luther Vandross and James Cleveland, and one of my really close friends was one of her booking agents, Ruth Bowen.

Ruth Bowen was a major character. She knew her for years and years and talked to her every day and so in any event I just thought if I don’t do this book with Aretha knowing the people that I do and having entered her world, who will?

And so, I made up my mind to do it but what’s interesting about the book, and it occurred to me when I was deep into it, was that this could only be written by a ghostwriter because, even though it’s not a ghostwritten book, when I do my interviews I let these other people go on for pages talking about her, and I don’t feel inclined to put everything in my voice - most biographers tend to put everything in their voice, but I’m happy to turn the microphone over to interviewees and I do that because I’ve been trained to do that as a ghostwriter, so consequently my hope is that you have all of these characters who come to life and have their own point of view about it.

PB: So, some of your subjects have been great candidates for collaboration. but have you got yourself into a situation where you just know it’s not going to work smoothly, where you encounter resistance but you’ve already agreed to go ahead? Do you get a sense of how it’s going to go right away?

DR: When you get a contract to do a book and the person really, really doesn’t want to dig deep and look at themselves--it’s all about self-reflection and self-analysis--and when people are not inclined to do it, it’s hard.

When it doesn’t work in other words, my technique is when I’m doing interviews and I’m not getting anything, I usually begin talking about myself: about the problems I’m having with my mother, my father and telling stories about myself and I do that as an example of what they might do and it often works. I’ll tell some heartbreaking tale about me and my father, and I’ll get through to the person who will say, “Man, that reminds me of my dad or my cousin.” So it’s a way of breaking the ice and that’s all you can do.

PB: And you’re going to be working with Willie Nelson.

DR: I am now. We’re in the middle of revising the book right now.

PB: Does the process change when you transition to another musical genre or do you still largely focus on the interpersonal relationship?

DR: Well, you’re still working on the interpersonal relationship but, yes, it is different changing genres because you have to change your kind of rhythms and tones. When changing genres you have to be aware of tone - a country music book is much different than a jazz book. I love rhythm and groove. For me, for the book to work well it’s got to have a certain kind of beat and I’m a reluctant reader by nature. It's weird about me.

I’m not a reluctant writer. I’m an eager writer and a reluctant reader and I don’t love to read. The way I write is for people like me who don’t really love to read, so I want to make it easy for you to read and get you turning the pages and all that kind of stuff, so that when you go from an R & B book to a country book you’re really aware of the different tones of it and the rhythms and when I’m doing the Willie Nelson book, I’m listening to his music all the time, night and day, so I’m hoping that through that that gets into me and gets into the prose.

PB: So have you reached the comfort level needed to tell the story?

DR: Yeah. Willie’s great. He’s been a wonderful collaborator. He’s 81 and has nothing to hide and he’s an open-hearted man, a great guy.

PB: What’s it been like transitioning from writing nonfiction to writing novels?

DR: This is a weird thing to admit but there is an obvious difference - -in one kind you’re making up everything, the other you aren’t. There’s also continuity between the two. I find so many of the devices I employ in fiction, I use in non-fiction. I create a lot of dialogues. I write about a lot of dreams. I tend to be pretty free, and also when I’m writing fiction, I’m aware of the things I’ve learned in non-fiction, which is being true to a voice and I pretend that the fictional character is really there in front of me.

I find there’s this kind of bridge that’s easy to walk over between the two of them and I’m always going back and forth and so the adjustment, for me, is quite easy.

PB: So how involved do you get in the writing process? For example, now as you work on the Willie Nelson project, are you hard to reach? Are you totally immersed? Do your family members approach you gingerly and whisper, ‘David, are you there?’

DR: I am, but I’m not. First of all, I’m always working on two or three books at the same time and this year I put out five books. There was Andrew Dice Clay, Joe Perry, Aretha, a book I wrote with Tavis Smiley about Martin Luther King last year and the autobiography of Rick James. At one point, I was working on at least two or three of them at the same time. Now, in addition to working on Willie’s book I’m writing a book with Marvin Gaye’s wife, Jan Gaye, about her relationship to Marvin, and Tavis Smiley and I are working on another book together about Maya Angelou and so, no, you can call me. I’m not hiding out. I’m at home; my wife and I. Our children are grown. We have grandkids. We have our dog, who I take out three or four times a day on a walk. I feed the dog and watch TV at night and work during the day. It’s pretty uncomplicated, but, no, I don’t just go in a cave.

PB: When writing with a comic like Don Rickles, there’s an expectation that the book has to be funny…

DR: It’s hard. In fact, one of the hardest things to do is to do a book with a comic just because of what you’ve said. Where’s the laugh? You’ve got to provide the laugh but it’s another kind of challenge. In another lifetime, I would have loved to have been a ghostwriter for politicians. I like to write other peoples’ speeches. I don’t think in my old age it’s going to happen to me, but I would have loved to have written a presidential inaugural address and again it’s just ghostwriting.

You’re pretending you’re another person and you have to capture their voice.

PB: Thank you.

Picture Gallery:-