published: 14 /

11 /

2014

In his second Pennyblackmusic interview, 1950's and 1960's soul legend Little Anthony chats to Lisa Torem about his group the Imperials, fifty year career and new autobiography

Article

It is almost impossible to keep up with Anthony Gourdine’s boundless energy and imaginative projects. Gourdine is a talented solo singer, recording artist/actor and lead singer of Little Anthony and the Imperials. It was an emotional Smokey Robinson that inducted the legendary group into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2009. Originally Clarence Collins, Ernest Wright, Sammy Strain and Anthony, the group disbanded in the 1970s but enjoyed their Madison Square Garden reunion in 1990 so much that they returned to the limelight (with later line-up changes) and are still taking Las Vegas by storm with Robert LeBlanc, who replaced Sammy Strain in 2004.

‘Tears On My Pillow’ brought them major success in the 1950s as did ‘Shimmy Shimmy Ko Ko Bop’ in the 1960s. Teddy Randazzo wrote ‘Hurt So Bad’ and so many other beautiful ballads, which were tailored to Anthony’s golden falsetto and animated personality.

Currently, Anthony performs with the Imperials, with selected orchestras, and with a pianist in New York City and is returning to the studio for some surprises. He recently recorded ‘World Without Love,’ which appeared on a Linda McCartney tribute album and is thrilled to perform in a Paul McCartney charity benefit.

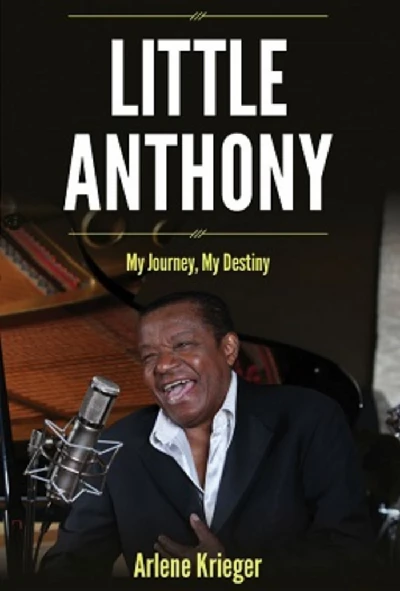

He has recently undergone extensive interviewing for his heartfelt biography, ‘Little Anthony: My Journey, My Destiny’, with Arlene Krieger, which unveils an absorbing backstory in and of itself. Back for his second, in-depth Pennyblackmusic interview,

Anthony Gourdine shared life-affirming stories and admiration for all types of music.

PB: I was wondering what prompted the publishing of ‘Little Anthony: My Journey, My Destiny ‘this year.

AG: This had been going on for years. I like to talk and I didn’t realize that when I talk about the things that I’ve experienced people sit around me like I’m the pied piper.

One person said, “You’re a historian because you lived at a time that none of us experienced, so when you talk about these people you talk about them like they were still alive.” And they are. They’re inside of me. My relationships with all of them were real.

George Dassinger said to me one day, “Every time you open your mouth you say something you didn’t say before.” People always tell me, “You should write a book. You should write a book.” And I would also tell them that I’m still living it. That was just a way of protecting my emotions because nobody was knocking down the door for me to do a book.

George and the other people in my life went out and explored that idea, and most of the time there was total rejection. “We don’t do any more autobiographies. That stuff doesn’t sell.” And there’s 100,000 books out there; people talking about their lives. So, it really wasn’t something I was thinking about.

But I’m a man of faith. My whole life has been like that. It seems like I’m always pushing in a certain way. I was doing a gig in Las Vegas at the Cannery East last year some time, and my road manager said there was a lady who came here, Arlene Krieger, and she said to give you these books and read them because she was interested in doing a book. So, that was the beginning of it becoming a reality - not because I was pursuing it. It just happened.

I actually didn’t even talk to her for about two months. But then I was lying in my bed-- I had left the book on the side in a bag. I looked at a book and called my son, Tony, who is my business manager. I said, “Tony, there’s this lady who came in about two months ago…” Tony said, “Call her.” And that was the beginning.

She’s a delightful lady who lives in Las Vegas. She gave me her credentials. She works with Mascot Books, a midrange carrier. She called her publisher and one thing led to another.

Arlene said, “You’ve got an interesting life and maybe we should do something.” So, the publisher flew out to see me and we went to a hotel and sat and talked for about two hours - he just sat there and listened to me. He’s a very young man, probably in his thirties. And he didn’t really know me. He knew of me.

And I would sit there like I do with everybody. I hold court. He’d say, “What do you mean? You knew Jimmy Reed? Wasn’t he a great blues singer?” I’d say, “Oh, yeah. Jimmy and I would drink a lot of booze together.” He was an alcoholic and he was the greatest Delta blues singer that ever lived. And he was real and he had several hit records, such as 'Baby, What You Want Me To Do?'

He’d say, “You mean you (two) used to ride around in a bus?” And I would talk about David Lynch and the Platters and Paul Robie and Zola Taylor and all of these people. And he said, “What?” And I would talk about Sammy Davis, Jr. and it would just come out. I didn’t even realise I was living that kind of life. I was so high on drugs half the time I didn’t know where I was.

It was memoirs. I didn’t know. Somebody told me, “You have total recall. You remember dates, times and what you felt emotionally. Boy, if you ever can get that down on paper…”

I could have made it sensational or “I did this one on the subway tracks”, but that’s not what I was coming from. What I wanted to say was - there’s this kid who was in Brooklyn, New York, and he lived in the hood, the ghetto, the projects with no real future - he had this wonderful relationship with his aunts, my mother’s sisters, who were all Gospel singers and they were very well known, as the Nazareth Baptist Gospel Singers, and that’s why my mother used to bring me around to all of those different churches. My mother was planting a seed in me, who I was to become now and these wonderful relationships led to other relationships - I knew Sam Cooke when Sam Cooke wasn’t Sam Cooke (Laughs). He wasn’t a solo singer. He was singing with a group, the Soulsters, a Gospel group. He used to come over to my aunt’s house.

Leslie Uggams lived down the street, so I got to know Leslie and her mother; meeting Duke Ellington and Count Basie, it was crazy. It was a magic carpet ride and my life was just not singing ‘Tears on my Pillow’ - it was something stronger, something bigger that was directing me. I didn’t know what it was. And every time I looked up I always landed on my feet. I used to hang in drug dens. You don’t hang in drug dens and live. I used to watch guys take heroin, and the only reason I didn’t take heroin is because one of my brothers was hooked on it, and I said, “I’m not going that way.” We call that mainlining, but I used to snort it and any other drug I could think of. I came out of the streets. My heroes were pimps.

PB: And for a time you joined a violent street gang.

AG: Many of my friends got killed. They were called the Chaplains. A great Evangelist came out of that gang, Nicky Cruz. And I came out of that gang. The foreword of the book references Jeremiah 1:5 from the Old Testament: “I knew you before I formed you in your mother’s womb.” I just really believe that there’s a destiny made up for all of us and I realise now at my age that this is not a mistake. It’s not even a mistake talking to you. It just seems to be falling in place at an older age. In fact, I’m having more fun now than I’ve had in my career. I’m not making as much money, but it sure is a lot of fun.

PB: What do you remember about the famous Apollo Theatre? It must have been thrilling to go there when you were just a kid.

AG: I remember the power of the Apollo. I’d walk a couple of miles to go there. I was a kid, so it was nothing. I would go backstage and watch the acts go in and out. I’d see the girls screaming and wanting autographs, and I would just sit there and look not knowing that in a few years I’d be in there.

We used to sneak into the Apollo. We knew how to do it. We’d stay there all day long from morning until night. They used to have six or seven shows a day until the midnight show and they’d show movies in between, so it was a pretty good deal.

I saw this group, the Turbans. They came out with these turbans and I was thrilled when I saw the Moonglows, who were huge, and the Flamingos.

PB: When you saw these groups, did you imagine yourself being an entertainer sometime in the future?

AG: Not yet. I sang but I didn’t know if I was good or bad. I just knew I could hold a note and harmonise. It was just the thrill of seeing them do it. Now I’m thinking, “When did it happen?”

I think it happened when Clarence Collins, one of the Chesters, which became the Imperials, once asked me: “Hey, man, why don’t you go down to the famous talent show at the Apollo?” I was scared of failure and I didn’t want to do it, but they did it and came in number two and were trying to get me to sing with them. So, I thought, there might be something to this, and then this guy in 1955, Paul Windley, decided he wanted to put a record company together called Windley Records.

I was with the DooWops when he heard us. We auditioned on Broadway. He was telling us what he could do for us - he was just a small time guy. That’s when I started thinking, “You mean, I could make a record? A real record?”’ You know how you could put a nickel in and hear the sound of your own voice? That’s how far I got.

Once I had done something at Pope Studios with my cousins, who were in a Gospel group. I must have been twelve, thirteen. That was the only time I had been in a studio but it wasn’t a major studio. And this guy said he could record us in a major studio. I was about fifteen and then he actually does it. He got our record played locally and I heard it on the radio. I was stunned.

PB: Ethel Mannix introduced you to classical music. You have an amazing ear for melody, harmony and overall arrangements. Did that early exposure inform your skills?

AG: You hit the nail on the head. My mother, my aunt and Mrs. Mannix were the catalysts that moved me towards becoming a professional singer. They were planting seeds long before I thought about it. Mrs. Mannix used to have Music Appreciation Day on Wednesday. You could go out of her class and play baseball, or you could stay in the class and listen to classical music. She put the masters on. But, obviously, 90 percent of them were out there hitting the ball.

Edgar and me were the only two kids (Laughs). There mostly were girls. Mrs. Mannix used to hear me sing and she told my mother, “He has a gift and you should put him in something.” She put me in Star Time Studios where you’d get to sing on local TV, but you had to go through this process. Mrs. Mannix knew that the more experience I got the better I was going to be.

I was always a dreamer. I would look out the window and look at the birds. I was Ferdinand the Bull.

PB: Out there smelling the flowers?

AG: I was a lover, not a fighter. You know that stuff boys do? You had to question yourself. Am I a guy? But years later I found out that’s why God put that sensitivity in me and it was people like Mrs. Mannix that pulled it out.

She played a song called ‘Ruby,’ a semi-classical pop song that was a big hit in 1953. (Anthony sings). It fascinated me. It was in me. It was pretty and I like pretty things. In fact, I love artwork. I go to museums. That’s the kind of guy I am until this day. I’m interested in that stuff, and it was Mrs. Mannix that opened the door.

She’d sit me down and play Beethoven. Then she told me stories about Beethoven being deaf. And I thought, “What?” I listened to the third movement and it was so intricate to me. I thought, “How could anybody even think of that stuff?” And finally I got to Wagner, the greatest Anti-Semite that ever was in Germany, but yet his music was outstanding: ‘Tristan und Isolde’. I was just listening to this yesterday, Franz Liszt. Then I began to read about them. Who are these people? Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart was writing symphonies at nine-years-old. How can they do that?

Mrs. Mannix opened these doors for me. She used to smile and play that music and I’d be looking out the window, listening. She knew that something wonderful was happening to me. She had a great influence on me. I have a dream to go to Italy and go where all the great opera singers come from - Luciano Pavarotti. I began to listen to Pavarotti over thirty years ago and I studied everything he did.

I was almost going to do one of his great arias: ‘Nessun Dorma’. I didn’t do it but Aretha Franklin did a marvellous job. People don’t know Aretha is an accomplished pianist.

So, it wasn’t just me. Many people in this business have been drawn to that.

Once I went to see Mantovani. When you go to Carnegie Hall you’re supposed to dress up and everything. My manager, Richard Barrett, loved classical music so he got us these tickets. We were sitting down and everybody was looking at us, like, “Who are these black kids coming to see the great Mantovani?” And Ernest comes in from behind, late, wearing these shoes, and before the master turns around for the down beat, you can hear them going,”Squeak, squeak.” He’s like Bugs Bunny. ‘”Excuse, me, pardon me, excuse me, pardon me.” And the master had his baton up and he turned around and looked like, “What the heck?”

So, Mrs. Mannix opened the door for me in music that I think serves me well today.

PB: So, how do you feel about performing with the current line-up of the Imperials and how long has the most recent member, Robert LeBlanc, been working with you?

AG: Robert has been with us for five years. (LeBlanc, who worked with Marvin Gaye, Aretha Franklin replaced Sammy Strain, who retired in 2004 - LT). This is not really the Imperials. Ernest is the remaining survivor. Sammy Strain, Clarence Collins, Ernest Wright and myself and I’m Little Anthony and I’m a different entity now. They’re the Imperials. We have some good people there.

It’s like you’re using a brand and people want to know there’s somebody out there. I hate to say this, but I can go out there with anybody and call them the Imperials and the audience would probably go for it because they want to hear me sing.

I’m doing a solo thing in March in Tampa, Florida with just me, two girl singers and a guy and a rhythm section. I’m doing that one with Mary Wilson.

PB: And you’re also doing a show in New York with only a pianist?

AG: Yes, I’m multi-talented. A lot of people don’t know that. With the pianist, I’m not reinventing the wheel. Billy Crystal had done it. Mike Tyson has done it. But I’m just doing it – me - and it’s been successful and I have shows coming up in New York City at the Cutting Room and the other one is in Connecticut at a theatre. And it’s almost sold out - 900 people.

PB: You’re performing ‘A World Without Love’ at The Many Moods of Paul McCartney tribute in North Carolina. Your version is so different than the original McCartney song recorded by Peter and Gordon. What kind of response are you getting for that version and, secondly, how do you compare the ballad writing of Paul McCartney to, say, Teddy Randazzo, who wrote so many of your hits?

AG: They’re two different animals, two different styles. I wasn’t a Beatles fan in the beginning. I didn’t even like them. In fact, George Harrison invited us to open for him at Shea Stadium when they came here in 1965. When we heard about the Beatles, we didn’t know who they were. We had the number two record (‘Goin’ Out of my Head’ - LT) behind Diana Ross in the country. We didn’t want to open for no bugs. Who knew?

The Beatles were blowing up. They had just been to the Ed Sullivan Show. We found out that George Harrison and maybe somebody else in the group loved Little Anthony and the Imperials, so they wanted us to open for them. But we were so arrogant, such egotistical young people that we didn’t get it and we didn’t have the kind of management and foresight and creativity and vision to say, “Yeah, guys, we’re going to do that.”

There were only a few groups at that time holding their own. One was the Drifters. The other was Dionne Warwick, and the other was us because everybody had fallen by the wayside because we had top seven, top ten, top five right there.

PB: One day another little boy called you the “N” word. Your mother sat you down to discuss it. You said, “That was one of the hardest days of my life. I knew it was hard on my mom.”

AG: I was ten-years-old and it had not been a good couple of years. This kid said it and I’m sitting and thinking, “Why?” and my mother had to sit there and tell me, “This is the way it is.’ And then I faced all of this in the South, the humiliation. I had to endure that and it was my mother who said, “No, you’re not going to quit the tour.”

Everybody was trying to talk me out of it. Bo Diddley was saying, “You’ve got to be a man. You’ve got to grow up. This is the real world.”

I thought, “I don’t care about the real world. I make my own rules,” and in my world it’s flowers and pretty music and good people. So my mother really got me to grow up when she said, “Boy, you’re not coming home. You stay out there and do that tour. You gave your word. You stick to it.”

I said, “Mom, dad”’ She said, “We’ll talk on the phone. You call me. We’ll talk.” I said, “I hate it. I hate it. I hate it.” I remember Christmas Eve I cried because I had a little radio in a seedy hotel in Richmond, Virginia, because we couldn’t stay…there was still segregation. We stayed on the other side of the tracks in some sleazy—and here I am, Little Anthony. Why am I living like this?

PB: And you had lived in a close-knit, multicultural neighborhood all of your life so it must have been like wham…

AG: Pow. I was sheltered. My friends were Italians and Jews. There was Bobby Fasano; Puerto Rican kids. We used to call ourselves the Navy Street Gang because of the Our Gang show. There was one black kid or two and the rest were all white, but that’s who I was and we sat in each other’s homes; I Iearned to cook Italian by being in an Italian house.

I went to my friend’s house, she’s Jewish, and she said, “You know more about how we cook than we do.” That’s what I did at Tommy’s house about once a week; Tommy was a Jewish kid who lived under me. Bobby Fasano lived above me in the same apartment. So we would play together and if you played in the house the mother would say, “Do you want a sandwich? Do you want a cannoli?” I’m thinking, “What’s that?”

I got intrigued with it and to this day I cook anything. I’m a very ethnic sort of guy. I just love people. My daughter-in-law is Puerto Rican so I learned how to cook that. Cuban food, I learned, I learned Middle Eastern and Moroccan cooking. I learned Greek.

PB: Does performing now as an actor/singer present challenges you hadn’t face earlier?

AG: One of those things comedians fear is going blank and for singers it happens, too. It’s very rare but it will happen. It did already. I was doing a song, ‘I’m on the Outside Looking In’ and I’m thinking, “What’s the next line?” It totally runs out of my head. This is a very normal thing.

It is a challenge of challenges but it is so rewarding when you nail it. You say to yourself, “How can I remember all of that stuff?” It’s because of cue lines, which I was taught about by David Alexander, my drama teacher. It just sparks the moment of that particular play or that scene. It’s hard to explain.

I’m a slow study. Bogart was a slow study. There are many slow studies. James Cagney was a slow study.

PB: But the fear of going blank live doesn’t intimidate you?

AG: It’s scary and exciting at the same time. When I did‘ Sistuh’s in LA for over a year--and there were some great people in that thing—I took three dual parts. I had so much dialogue that I used to go: Duh Duh Duh Duh Duh. Just before the curtain rises, I’m looking at my lines. Everybody’s got their own way of doing things to get it going but other actors depend on other actors.

PB: Could you see yourself working with some hip-hop artists or do you prefer to stick with the music you’re more commonly associated with?

AG: I don’t care. There are some people I like to listen to that intrigue me a little bit. Jay-Z can be off the wall or he can be very insightful. When we get ‘A Hard Knock Life,’ that’s insightful and creative. And he talked really about Brooklyn because he lived where I used to live. And I was impressed with that--that he turns around and goes into this street thing and if it was something like that, yeah!

PB: So, you could definitely see yourself collaborating with a reggae or hip-hop group?

AG: I don’t care. I’ve done jazz. I’ve done stuff that’s not commercially acclaimed, but artistically acclaimed. I did one album where we turned the songs from a Broadway musical around and did it in a smooth jazz way. Why? Because it’s fun and creative and people have to be creative.

But the people, the “suits,” they just think about money. If you’re doing business with them, they’ll have you sounding like everybody else. To get out what you’re trying to get out. Sometimes it’s not necessarily about how much money you’re trying to make, but it’s more about how many people you’ll affect.

PB: Finally, if you could be a super hero, which power would you have to have?

AG: I don’t really have an agenda. I probably would do what I always try to do - give back to people emotionally. I found that I’m a great motivator. Many people tell me that. That’s why I liked Superman so much as a kid. Superman was so cool. He was able to leap from tall buildings with a single bound. He’d always be there for people when they were in trouble. He came from Krypton, which was going to blow up so he had a destiny. It’s like the book. Superman had a destiny.

PB: Thank you.

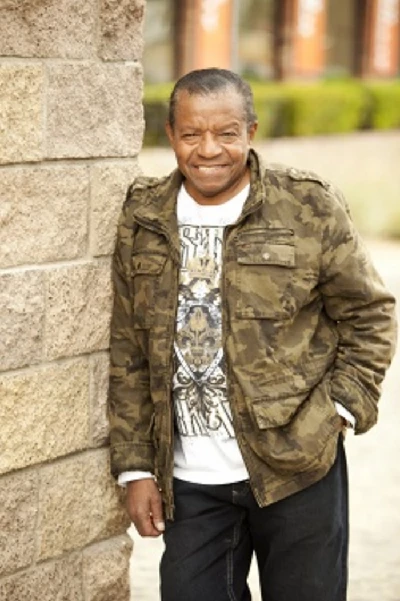

The top two and the last photographs that accompany this article are by Bobby Black. The second last photograph is by Clarke Mayer.

Picture Gallery:-