published: 3 /

5 /

2014

In the second part of his three part series on the Velvet Underground's second LP 'White Light/White Heat', Jon Rogers continues to reflect upon its seminal impact

Article

As Lou Reed put it in 2013, 'White Light/White Heat' drew the blueprint for "articulated punk", a cacophony of confusion, despair, horror and non-melody and distortion. Yet its mixture of stripped-down guitars, rudimentary rhythms and white noise influenced the generations to come.

The album opens with the frantic garage-guitar thrash of the title song, which referenced the temporary white light 'blindness' caused by crystal methedrine use ,and the three-minute song hurtles along at breakneck speed, mimicking the effects of the drug. Reed confirmed in a 1971 interview in 'Metropolitan Review' that the song was about amphetamines.

Although a less well-known inspiration for the song is Alice Bailey's occult book 'A Treatise on White Magic', according to Richie Unterberger, which talks about flushing your personality with "pure White Light" and goes on to give instruction on how someone can "call down a stream of pure White Light". Reed had certainly read Bailey's work, calling it "an incredible book" during a radio interview in Portland, Oregan in November 1969. While in an unpublished interview in 'ZigZag' conducted in 1972, Reed admits that he and Warhol associate Billy Name read Bailey's entire work, some 15 volumes.

Rob Norris in his 'Kicks' article 'I was a Velveteen' recollects Reed telling him that 'White Light/White Heat' was an example of "how a lot of his songs embodied the Virgo-Pisces opposition and could be taken two ways", adding that "Reed was very interested in a form of healing just using light, projecting light."

Wayne McGuire in 'Crawdaddy' described the song: "The track 'White Light/White Heat' best illustrates my contention that John Cale is the heaviest bass player in the country today. Most bass players play two-dimensional notes, but John plays three-dimensional granite slabs which reveal an absolute mastery of his instruments and a penetrating awareness of the most minute details of his music."

The song, backed with 'Here She Comes Now', is released by Verve in November of 1968 as a single, and does absolutely nothing to raise the band's profile.

The album then slows down and takes a macabre turn with Cale narrating Reed's story 'The Gift' which he had written whilst studying at Syracuse, the name coming from a short story by Delmore Schwartz written in 1958.

While the band effectively played a plodding version of 'Booker T' in one channel, Cale told the tale of Waldo Jeffers in a disengaged, laconic monotone which mixed in some dark humour with the hero ending up being unwittingly killed by his girlfriend Marsha after he mailed himself through the post. Jeffers own longing for his girlfriend to some degree reflects Reed's own longing for his then girlfriend Shelley Albin in 1962 when the pair could not be together.

While Cale's vocal was swiftly done in a single take, unfortunately, the sound effect of Reed squashing a cantaloupe with a wrench - to indicate a knife going through a skull - was largely lost in the mix.

"I wrote 'The Gift' while I was at college," Reed told Lester Bangs for 'Creem' in May 1971. "I used to write lots of short stories, especially humorous pieces like that. So. one night Cale and I were sitting around and he said, 'Let's put one of those stories to music.' So, we did and I still wasn't sure about it - I'm never sure about things I write for about two weeks - but I guess it turned out really good."

The macabre theme is continued with 'Lady Godiva's Operation' - "a radio-theatre piece," as Cale called it and a surreal, William Burroughs-influenced tale with Gothic overtones about what appears to be a sex-change operation (or possibly a lobotomy) but it is hard to tell exactly what is going on as the guitars sweetly buzz along. Whatever it is, it's not pleasant. With the operation underway the patient, strapped to the table, starts to come round and begins to scream. Then the surgeon apparently seems to change his mind and starts making incisions elsewhere on the body. As Reed explained in 'Between Thought and Expression: Selected Lyrics of Lou Reed', his teenage experience of electroshock treatment might have given him inspiration for the song.

'Here She Comes Now' at just over two minutes is a slither of a song, but still quite effective and showcases the band's gentler side and is perhaps the album's most conventional rock song. It was originally to be sung by Nico when they played it live, but Reed handles the vocal duties admirably.

Still, there is a darker aspect to it than just a simple love song, as Reed explained: "There's the gender confusion in the song. Fear of sleep. The perfect thing for the people we were running around with, staying up fifteen days at a time."

Victor Bockris and Gerard Malanga though described it as "a rather pretty four-line dissertation on the possibility that a girl might come." A view Reed seemed to agree with in a May 1972 interview with 'Time Out': "We put out 'Here She Comes Now' [as the b-side to the single 'White Light/White Heat'] in San Francisco and they said 'that's about a girl coming,' and I said, 'Well, no it's not, it's about somebody coming into a room.' And then I listened to the record and I realised it probably was about a girl coming as matter of fact, but then again, so what? But we were banned again..."

The song though just lulled the listener into a false sense of security as they flipped the record over and were greeted by the barrage waiting for them on side two.

'I Heard Her Call My Name' is four minutes of violent, out-of-control guitar thrash that does leave your "eyeballs on your knees" and your "mind split open" as the band unleash a blitzkrieg on the listener's ears. The death theme is once again present as the female subject of the song is dead, and the singer is haunted by her saying their name. The guitars were turned up to the fore in the mix by Reed after the band had completed work on the song and he went back into the studio to remix the tape. The move would cause a serious argument within the band with Morrison walking out on the band for a couple of days, as he objected to what Reed had done behind their backs and it was a song he considered one of their best.

Even Moe Tucker, usually a stabilising influence on the three men, was irked by Reed's actions. "When he remixed that, he turned the guitar solo way up and because he did that, the rhythm section was drowned out and the solo just became this noise. It was a stunning solo when you could hear the rhythm going on, not just Lou blasting away, and still when I hear it, it breaks my heart. In my view it's totally ruined, a real bone of contention."

She expanded later in Bockris' biography of Reed: "[It] was ruined by the mix - the energy. You can't hear anything but Lou. He was the mixer in there, so he, having a little ego trip at the time, turned himself so far up that there's no rhythm, there's no nothing."

Reed had in mind Jimi Hendrix's style of guitar playing for the song, telling 'Uptight': "When Jimi Hendrix came over the most striking thing beside his truly incredible guitar virtuosity was his savage, if playful, rape of his instrument. It would squeal and whine and going off into a crescendo of leaps and yells that only chance could programme. Anyone who does that night after night must go mad. It was the frenzy of self, for frustration can only be acted out in violent ways, never mime. If any part of it becomes sham, then vital energies are used to mimic the worst aspects of self and both mind and body are soon exhausted."

Ornette Coleman also influenced Reed's playing in general, but also on the particular song. Reed would hear the saxophonist play at the Five Spot but would stand outside as he could not afford to go in. "I wanted to play like that," Reed told Fricke. "I used the distortion to connect the notes, so you didn't hear me hesitating and thinking." The rest "was based on what an overloaded Fender amp can do. I never thought of it as violent. I thought it was amazing fun."

The song was, however, not just noise, as Tucker noted in 1994: "It went with the song...with what he wanted to be doing. It was him against the amp. You listen to it, and it's a solo."

In an interview with the 'Metropolitan Review' in 1971 Reed explained that the song was "about someone who was very strung out... [with] his eyeballs on his knees. And then he hears her calling him. Everybody has a her. You can hear it in your mind."

'I Heard Her Call My Name' though is just the appetiser for the album's centrepiece, the seventeen-minute 'Sister Ray' - a sort of lo-fi, way before the term was coined, musical version of Herbert Selby Jr's novel 'Last Exit to Brooklyn'. While bands like the Doors had elongated the typical three-minute pop song and explored dark themes like Oedipal desire, 'Sister Ray' ratcheted up the stakes by a considerable distance and tested the listener's endurance skills.

It is hard to tell exactly what is going on in Reed's tale of the denizens of the Lower East Side, but it has something to do with the transvestite Sister Ray and 'her' drag queen friends picking up some sailors, shooting smack and indulging in an orgy. And somewhere in all of that someone called Cecile seems to shoot the sailor. Or something along those lines. It's hard to tell just exactly what is going on as the lyrics are drowned out by the duelling guitar noise and distortion, an organ also battling to be heard above the din and Tucker's thunderous pounding on her drums as she tries to hold everything from spiralling out of control. The listener can only catch snatches of Reed's lyrics, like "Sucking on my ding-dong" before they are lost in yet another wall of noise.

At the point where Reed sings "Who's that knockin'" Tucker was going to tap the rim of one of her drums, but Wilson forgot to turn on the mic at the right moment and so it sounds like she's just stopped playing. A mistake that would leave Tucker infuriated, as she told the fanzine 'What Goes On' years later.

"We were doing the whole heavy metal trip back then," stated Reed. "If 'Sister Ray' isn't an example of heavy metal, I don't know what is."

Lou Reed tried to explain what the song was about - "I like to think of Sister Ray as a transvestite smack dealer. The situation is a bunch of drag queens taking some sailors home with them, and shooting up on smack and having this orgy when the police appear."

T

he song, a long jam, came about in the studio, as Reed explained in 1971 in Lester Bang's 'Creem' interview with: "We didn't use any splices or anything. I had been listening to a lot of Cecil Taylor and Ornette Coleman, and wanted to get something like that with a rock and roll feeling. And I think we were successful, but I also think that we carried that about as far as we could, for our abilities as a band that was basically rock 'n' roll."

Reed expanded on that in a 1976 interview for the 'NME' with Lenny Kaye: "When we did 'Sister Ray', we turned up to ten flat out, leakage all over the place. That's it. They asked us what we were going to do. We said 'We're going to start'. They said 'Who's playing bass?' We said 'There is no bass'. They asked us when it ends. We didn't know. When it ends, that's when it ends. It did a lot to the music of the Seventies."

Morrison remembered the song as an all-out battle between the musicians to see who could play the loudest, stating in the booklet for the box set 'Peel Slowly And See': "When Cale came surging through the wall of sound on his first solo, I remember thinking, 'Where's John getting all that noise from?' I see him fumbling over there with all the stops on his organ. I expected it more to stay at the same volume. And all of a sudden, the organ is way louder than me and Lou. I couldn't turn up; I was already maxed out. At one point, I was down at the bridge pickup on my Stratocaster, so I decided to get a little more oomph on the neck pick up. So. I switched to that, which was good. I can hear it in there."

The song was not though entirely improvised with 'Sister Ray' evolving from an earlier framework of song called 'Searchin'' which contained the line: "Searchin' for my mainline." Reed wrote the lyrics to 'Sister Ray' during a train ride back from a bad gig in Connecticut.

'Sister Ray' had already been featured in the band's set list at the Boston Tea Party in May, and would become a regular in their set list with the band often elongating the song to sometimes approaching forty minutes. The band would later take the song off in different directions, often playing the introductory 'Sweet Sister Ray', also known as 'Sister Ray Part 1'. There was also a 'Part 3' as John Cale noted in his autobiography: "I don't think anyone's got 'Sister Ray Part 3' on tape that we used to do as our big finale. We'd start way off... with something totally chaotic and gradually work our way back to the version on the record. Very long, very intense, with Lou becoming a Southern preacher man, telling stories and just inventing these fantastic characters as we played."

As Cale stated in his autobiography: "My fondness for long passages of grinding noise clashed with Lou's attempt to take the band towards the more commercial. It was chaotic, certainly, but never the free-for-all most people suppose. There were moments clocked in my mind that I'd worked out to have certain things happen. The free-form songs like 'Sister Ray' would have definite points by which I could signal that it was time to move on a stage. Markers on the long improvisations. Lou and I shared this sort of subconscious understanding about when to take it up or down."

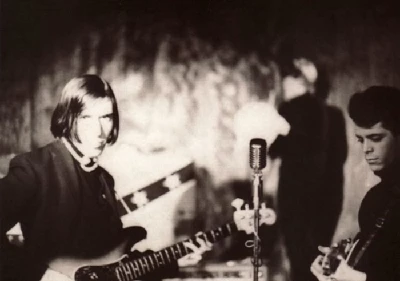

Picture Gallery:-