published: 27 /

8 /

2012

The Velvet Underground's classic 'The Velvet Underground and Nico' will be re-released in October in a five CD box set. In a multi-part series, Jon Rogers writes of the band's history up until its release. He begins by examining their first few months together

Article

On 6 March 2007 the Velvet Underground's debut album 'The Velvet Underground & Nico' was included in the Library of Congress's National Recording Registry. At the time it was one of only 225 recordings to be given that status. On the Library of Congress's website it explained why the recording had been included:

"For decades this album has cast a huge shadow over nearly every sub-variety of avant-garde rock, from 70s art-rock to no-wave, new-wave and punk."

It was a statement critic Lester Bangs would have agreed with as he once wrote: "Modern music starts with the Velvets, and the implications and influence of what they did seem to go on forever."

But at the time of its release, in early March 1967 in the US and November for the UK, no one really cared. The album with its now iconic cover designed by Pop artist and the band's patron, Andy Warhol, limped into the 'Billboard' chart at a dizzying 171 and failed to register in the UK.

Former Roxy Music member Brian Eno neatly summed up the album's influence: "Only a few thousand people bought that record, but all of them formed a band of their own."

The band itself was a composite of various stark contrasts - the unskilled musician aesthetic of drummer Maureen 'Moe' Tucker was set against the classically schooled John Cale, who had studied and worked with some of the most renowned contemporary composers of the day. In contrast to that there was Lou Reed, streetwise and admirer of writer Delmore Schwartz, and whose lyrics depicted a New York demimonde of hustlers, pimps, whores and junkies as if straight out of Herbert Selby Jr's novel 'Last Exit to Brooklyn'. But Reed also had much love for doo-wop and the jazz giants John Coltrane, Cecil Taylor and Ornette Coleman, and before forming the band worked as a song writing hack for Pickwick Records.

Then there was guitarist Sterling Morrison, detached from the dominant personalities of Reed and Cale, but who just got on quietly with doing the job in hand without fuss or histrionics. Morrison and Reed would become friendly via a mutual friend Jim Tucker, and bond over a love of R 'n' B and rock 'n' roll, and in particular Ike and Tina Turner.

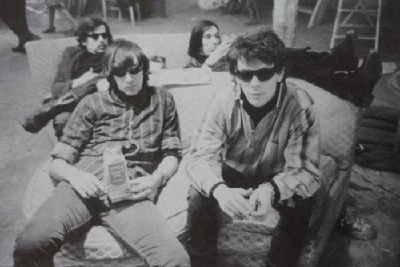

Never quite an integral part of the group but also a member was the Germanic singer Nico, who was a former model and actress, as well as part of Andy Warhol's Factory crowd. She was icy-cool with a deep Wagnerian-style voice, and her contrast from the rest of the band was even obvious at the early gigs where usually the band would be dressed all in black, with dark shades while Nico would be all in white.

The origins of the band, who took their name from the pulp/trash novel published by Macfadden Books in 1963 and written by Michael Leigh, were steeped in the avant-garde modernist composers. Welsh-born Cale had originally studied under Humphrey Searle, a one-time pupil of Anton Webern, at Goldsmiths College in London before moving onto more conceptual compositions in the style of John Cage, the Fluxus group and La Monte Young.

Gaining a scholarship to Tanglewood, he moved to New York and came under the tutorship of Iannis Xenakis and managed to reduce the wife of conductor Serge Koussevitzky to tears after performing a piece that involved him smashing up a table with an axe. He went on to perform with Cage and was part of the group of pianists that took part in a marathon performance of Eric Satie's 'Vexations' on the 9th and 10th September 1963 at the Pocket Theatre in New York. The performance lasted from 6 p.m. on the 9th until 12.40 p.m. the next day.

He then went on to join Young's minimalist ensemble the Theatre of Eternal Music, which played elongated drones, steeped heavily in Indian music. He electrified his viola and, instead of using conventional strings, re-strung his instrument with electric guitar strings and let lose earth-rumbling drones at high volume. Young's compositions, such as 'The Second Dream of the High-Tension Line Stepdown Transformer', 'X for Henry Flynt' and the tetralogy 'The Four Dreams of China' sound very unlike anything really heard in Western music although perhaps the closest thing was the free jazz of Sun Ra or Albert Ayler.

Three of those musicians - Cale, violinist Tony Conrad and drummer/sculptor Walter De Maria - would end up being hired by Pickwick to back Lou Reed on the novelty record 'The Ostrich' which failed to make its mark on the American public. But the musicians were suitably impressed by Reed, especially Cale who saw a similarity in what the group was doing to what Reed was experimenting with by his unconventional tunings and modes. Reed had initially been interested in journalism and creative writing and studied under Delmore Schwartz at Syracuse University before falling for the charms of rock 'n' roll and turned his hand to song writing.

To earn a living he had joined the Tin Pan Alley industry in the form of Pickwick where he churned out commercial songs that mimicked the fashions of the day. If a surf sound was currently 'hot' with the kids, then he wrote a surf song. But Reed always kept an eye on more interesting developments and developed his "ostrich guitar" where he would tune all the strings to the same note and then thrash away.

As Conrad told the Velvet Underground fanzine 'What Goes On': "We couldn't believe that they were doing this crap' just in a strange ethnically Brooklyn style, tuning their instruments to one note, which is what we were doing too [with La Monte Young]. It was very bizarre."

Morrison was brought into the group after bumping into Reed on the subway's D train, around the 7th Avenue stop in April 1965 and with Angus MacLise (another member of the Eternal Music group) on drums an early version of the Velvet Underground was formed. Initially the band played art happenings and underground film screenings, but when more conventional rock shows were lined up and there was the prospect of the group actually being paid MacLise quit. This was partly because of what he saw as the commercialisation of the band's music, and partly because he objected to any format that forced him to start and stop at specific times.

Hastily looking for a replacement drummer at short notice with gigs coming up, the band came across Tucker whose hard, relentless, minimalist pounding had been developed by her drumming along to Bo Diddley records by stacking up piles of phone directories. That seemed to be the extent of her musical education apart from some clarinet lessons at school and playing drums in a trio called the Intruders who managed to play a couple of gigs in Long Island.

Plus they were in the extremely rare situation of having a female drummer. Even nowadays the sight of a female drummer often ensures a double take just to make sure, but in the 60s it was just about unheard of. As well, with Tucker's tomboy-ish looks, an air of sexual confusion surrounded the band with Tucker frequently being mistaken for a man.

Tucker was immediately won over by the songs she heard when she went round to Cale's flat, telling 'What Goes On' in their fourth issue: "I was very impressed when I first heard the songs, the few that I did hear at first. I remember when they played 'Heroin' I was really impressed [...] You could just tell that this was different."

That air of sexual confusion would only get worse once the band launched into songs like 'Venus in Furs'.

But the origins of the groundbreaking album 'The Velvet Underground & Nico' go back before Tucker even joined. In fact, according to 'Transformer: the Lou Reed Story', both 'I'm Waiting for My Man' and 'Heroin' which appear on it were initially written - at least in a basic form -sometime in 1963 when Reed was in his senior year at Syracuse and playing with LA & The Eldorado's. Apparently Richard Mishkin, a member of the band, helped work out the bassline of 'Heroin'. But thoughts of recording an album were some way off.

The first recorded take of any of the songs that will appear on the band's debut album was recorded at Pickwick Studios on 43rd Avenue, Long Island on 11 May 1965 with Terry Philips as producer. Who exactly was playing on the songs is unknown but it certainly includes Reed and Cale and possibly Jimmie Sims and Jerry Vance. According to Richie Unterberger in 'White Light/White Heat: The Velvet Underground Day-By-Day' three songs were recorded - a lightweight song called 'Buzz Buzz', and which features a rather banal lyric by Reed about trying to call his "baby on the phone" and all he hears is "buzz buzz buzz". Up next is the more accomplished 'Why Don't You Smile Now' featuring a Spector-esque blend of guitars and harmonica. The latter also recalls one of Reed's musical heroes, Bob Dylan.

But of most interest are the two complete takes of 'Heroin' - although the song is logged as 'Heroine'. Here the song has a 'talking blues' style with a folk styling guitar part and a rather rudimentary bass. While musically, the song is a long way from the final recorded version, lyrically the song is pretty much intact. Philips is clearly impressed and he can be heard saying, "Good performance." Reed though isn't so sure and says he's fluffed some of the lines and wants to take another shot. The second take is pretty much like the first, but with a stronger vocal delivery and the song abruptly ends after the line where Reed thanks God that he just doesn't care.

The tape finishes with two takes of an untitled John Cale piano piece which is very much in the style of La Monte Young and future Cale collaborator Terry Riley. Although it is only a slight piece it is interesting as Cale's incessant, repetitive piano playing will feature on 'The Velvet Underground & Nico', particularly on songs like 'All Tomorrow's Parties'.

It's highly likely that a number of early recordings of the band - featuring Reed, Cale and MacLise were made around this time. A fact confirmed by Tony Conrad in Richie Unterberger's book:

"There was a time around the early 70s, possibly the late 60s, [when] John was moving and didn't have any space for his stuff. So he gave me a huge box of reel-to-reel tapes that he really didn't have any way to use or play. He was sort of concerned that they might vanish, as things do when you move. But he knew that I was a pack rat, and so he suggested I hold on to them. Which I did." After about 15 years and after Conrad reminded Cale he still had the tapes, they were returned to Cale. What is actually on them is anyone's guess.

Perhaps the real start of what will become the Velvet Underground's classic album begins with the July 1965 demo recordings made where Cale and Reed are living together at 56 Ludlow Street in New York. Four of the six songs recorded now, on a Wollensak recorder given to Cale by Conrad, will be highlights of the album, and another will feature on Nico's solo debut album 'Chelsea Girl'. Perhaps more importantly, even though the recordings don't feature any drums, it is clear that by now a distinctive sound is forming out of all the various influences of the avant-garde, jazz, blues, rock 'n' roll and doo-wop.

What also is clear that Reed's lyrics have vastly improved. Only a month previously Reed had recorded 'Buzz Buzz' with its lightweight lyrics - a song Reed thought worthy enough to actually record at the time. Now though songs like 'Venus in Furs', 'All Tomorrow's Parties' as well as 'Heroin' and 'I'm Waiting for the Man' which addressed subjects like drug addiction, deviant sex and life on the Lower East Side showed that Reed had matured as a lyricist. And one that was prepared to break taboos. In 1965 pop songs were all about either syrupy teen love or the agonies of breaking up. The pain and pleasure of S&M and bondage didn't really get much of a look-in. The only contemporary of the Velvets writing songs about sex and drugs were the Fugs, who also happened to hail from the Lower East Side.

While Reed, Cale and Morrison are all present on the 80-minute tape, which will finally see the light of day as the first disc on the Velvet Underground’s 1995 box set 'Peel Slowly and See', the noticeable absence of MacLise is clear. It seems the reason he's not present is his artistic temperament. He's not one to be held to notions of time and schedules and so simply doesn't turn up.

This tape really marks the beginning of what can really be seen as the Velvet Underground - at least in a recorded form - and shows Reed's maturing lyrical style. It also shows just how far they have to go too. Even without MacLise the songs are very different from their final versions and the band sound almost like a folk group.

The opening 'Venus in Furs', a song about sadomasochism lifted from Leopold Sacher-Masoch's book of the same name, lacks the threatening menace and Cale's squealing viola. It's closer to fair maiden's in white dresses going to the fair than sordid fantasies involving whips and chains and leather.

'Prominent Men' is perhaps the weakest of the songs recorded in this session and is never released commercially until its appearance on the box set in 1995. It's very much Reed aping Dylan in his protest song era and includes what is probably Reed on harmonica - although he will deny this in a 'Q' interview in 1996. The song is just something of a nasal whine at stereotypical 'prominent men'.

Up next is 'Heroin', which includes two full takes of the song and is much closer to the final version recorded for the album. It is is pretty much done and dusted apart from the obvious lack of drums and a few minor changes to the lyrics.

Also virtually completed lyrically at this recording is 'I'm Waiting for the Man' except Reed does actually sing "... the man" rather than the later "... my man" for the version that makes the record. Musically it is very different closer to the country style of Hank Williams rather than the blues-rock pounding it will later take. Interestingly enough despite all of Conrad's avant-garde credentials he's a big fan of the country singer and he and Cale will often listen to him after rehearsals of their "dream music". Another difference in these versions of the song are that Cale gets to sing a few of the lines, unlike the final version which will have Reed sing it all.

'Wrap Your Trouble in Dreams' will never see the light of day in a Velvet Underground form (until the box set release) but will make it onto Nico's solo debut in 1967 and have a folk-pop feel to it with violins and flutes prominent in the mix. But the 16-minute section featuring this song on the tape - with a number of complete and incomplete takes - played by Reed, Cale and Morrison still highlights the band's folk styling and features Cale's singing, not Reed. Interestingly on this version of the song it features an extra verse not heard on the Nico version concerning finding happiness in death and loveliness in pain.

Why this song, clearly part of the band's repertoire, isn't taken further and at least even considered for the album isn't clear as it certainly has more commercial potential than the more outré songs like 'Heroin' and 'Venus in Furs'. Although that is perhaps it's very downfall, it just doesn't fit.

The final track on the CD from the demo tape is 'All Tomorrow's Parties'. The final album version paints a portrait of a self-pitying party-girl - widely seen as being inspired by Edie Sedgewick - but the versions here are rather different and more in a country/folk vein with Reed still imitating Dylan's nasal vocals.

Mystery still surrounds the recordings made at Ludlow Street and what exactly the purpose of making them was. Morrison, in the liner notes to 'Peel Slowly and See' by David Fricke, says they were initially just done for themselves and then only later they thought others might be interested and it could be used to attract record company attention.

According to Cale though this was just one of several tapes made around the same time and he believes 'The Black Angel's Death Song' was also recorded around then along with 'Never Get Emotionally Involved with a Man, Woman, Beast or Child'. The latter, it seems, to have been lost in the mists of time and doesn't even appear on any bootlegs of the band. He told 'Billboard' in the 19 August 1995 issue: "There's still stuff down there [the basement where the Ludlow tape was found] that I just haven't had the heart to... rummage around in. I knew, kind of, which boxes had what in them."

It would also seem there might be other material on the tape too as Polygram's Bill Levenson, in the same 'Billboard' piece, states that the tape he received was 94-minutes long and was then edited down to a more manageable 79-minutes so it would fit on a CD.

Certainly though a demo tape is made from the Ludlow Street recording(s) with the aim of getting a record label deal and despite the group's impoverished financial status Cale takes a trip to London in order to hawk it round the labels and drum up some interest. It is an unsuccessful journey. Even Marianne Faithfull closes the door on him. It is claimed that the future producer of Pink Floyd and Nick Drake, Joe Boyd, is given a tape but he later states he has no recollection of hearing about the band before the release of the actual album.

The purpose of the trip might have been a failure but it does give the opportunity for Cale to stock up 45s largely unavailable at the time in the USA and includes records by the Kinks, the Who and the Small Faces, amongst others.

These British rock and pop groups would make their mark on the band, if only directly. One record definitely bought by Cale was the Small Faces' debut 'Watcha Gonna Do About It'. The distorted guitar riffs and feedback on some, like the Who's 'Anyway, Anyhow, Anywhere' would at the very least give them confidence to carry on with their own experimental explorations and make them realise that other bands were at least mining the same sort of areas, if perhaps not quite as radically.

Tucker in her interview with the fanzine 'What Goes On' stated:

"We loved the Who. John had gone to England and come back with an EP of the Who. We had never heard them before, and he was raving. We heard that and really loved that. And we liked the Kinks, and the Stones, of course. We loved them. I did. They all liked them. I was a little crazier. The Beatles they liked a lot, and I was a big Beatle fan."

It is around this time former 'New York Post' reporter Al Aronowitz, famed for introducing the Beatles to Dylan, becomes the band's manager and he sets up their first ever paying gig on 11 December 1965 at a suburban high school in New Jersey. This is the catalyst for MacLise to quit who views being paid as going against his purist artist ethos, even if the band's fee is a paltry $75 between them. Plus he has no desire of being told when, what and for how long to play. As MacLise's wife, Hetty, explained to Unterberger:

"[With] Angus, everything had to be immediate. He couldn't really stand the thought of having to rehearse at a certain time, or turn up for a recording session at a certain time, because, maybe he wasn't actually feeling quite like it or something. Just when they were about to make a record, or make some money, then he would pull out. He would get tired of it. He wouldn't want to be involved in that side of things."

According to Aronowitz, in his article 'The Origins of the Velvet Underground', the reason why MacLise left wasn't down to any sort of artistic idealism and the fear that MacLise might be selling out if he got paid, but that he was reluctant to "carry his big set of bongos up and down five flights of stairs every time there's a gig."

Visitor Comments:-

|

|

594 Posted By: Myshkin, London on 26 Sep 2012 |

Now, I love the Velvet's just as much as the next person but has there ever been a rock band so over-valued and appreciated? No one has the guts to simply go: "Yeah a great band but not the holy grail of popular music." Music hacks are a load of sheep a lot of the time.

|