published: 1 /

2 /

2025

Steve Miles talks to Wreckless Eric about his recently republished, aptly titled memoir, ‘A Dysfunctional Success,’ and the man behind it.

Article

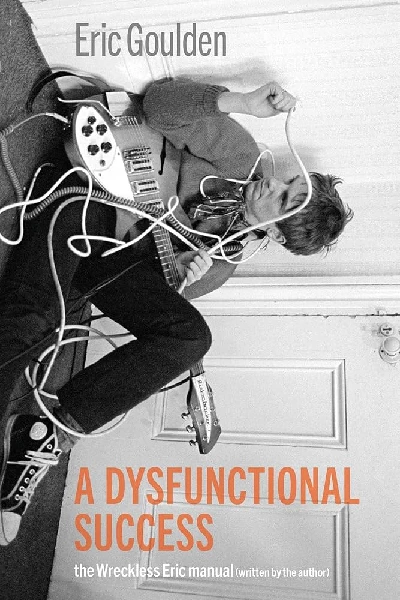

‘Wreckless’ Eric Goulden’s autobiography, ‘A Dysfunctional Success’, was first published in 2003, when he was approaching fifty, at a time when his early heyday was quite some way in the past, and the recent critical and commercial success he has been afforded seemed a perhaps-unlikely future. Previously hard to get hold of, it has now been republished this summer, with extra material, a new cover, and a more at peace author, who graciously gave of his time for this interview.

When I spoke to him, we looked back on the parts of his life that the book includes, but some of the areas it doesn’t. He talked candidly, with wisdom, good humour and generosity, about the highs and lows of his time on the planet, the ups and downs of the life of a ‘boy who felt he was a misfit’, and about the abiding influence, for good or ill, of our parents and our education on our adult lives. We talked about success, about peer pressure, self-expectation, addiction, punk, America, depression, and why he’s stopped running. We spoke about the people he’s known, from Elton John to Ian Button, his rock, Amy Rigby, and the daughter and granddaughters he delights in. We spoke for a long time from his new home in Norfolk and from that I have distilled the following. For once with me, it’s just his words telling his own story. Think of this as a taster for the book or an extra portion, depending on whether you’ve read it yet!

Over to Eric…

Am I at peace with myself now? Yes, I think so. As much as you can be. As long as I don’t catch sight of my reflection! You know, you have this image of yourself and when you see what you look like to other people, it comes as a shock. I think really you need to constantly re-evaluate your place in the scheme of things. I was 70 last week. I’m no spring chicken. If I look in the mirror and see a 50-year-old staring back at me, I’m smart enough to know that I’m deluding myself.

But I just love it sometimes when I see a new band and they can be anything they want to be, they come with no baggage. I mean, I actually want to make electronic music, and I have done for years, but I don’t dare to share it. I come with baggage, I come with an expectation, but you know in the past year or two the only song that I’ve done that’s not from my more recent and obscure catalogue is ‘Whole Wide World,’ and in the last couple of gigs I’ve completely deconstructed it. So I think if I do come with baggage, it’s pretty handy baggage: it’s not just fucking designer luggage!

Punk didn’t really exist, you know. There was a feeling in the air, kind of a movement going on, but it was not defined. It was defined and named by the press, and by the time they had named it, it had ceased to exist. The mistake we make is thinking that by giving something a name, we have defined it. I suppose in some way I feel like that about the name Wreckless Eric. It’s really a brand name. I couldn’t shake it. People would always put it on posters and I’d say, ‘Take that down,’ and they’d say, ‘Do you want to play to people or not?

The book started in a way with me doing a blog. And the thing about the Internet was that before that as an artist you could speak through the art you made, or the songs that you created or whatever, but it was always filtered through something. It was always filtered through what the record company wanted and if it wasn’t a thing that the shops wanted to sell they wouldn’t sell it, so it would have a very limited audience. But the Internet changed all this, and I saw that we have a voice, we can say what the fuck we want. I was terrible sometimes. I mean, I cringe at some of the stuff that I said, and I think sometimes I was a bit cruel and I should not have been, but it was fantastic that people could know me as the guy who did Whole Wide World and I’m talking about changing the oil in a car park supermarket in Sussex. Somehow the whole fucking thing went wrong and I ended up with this slick of oil all around the car, and me underneath the car covered in oil trying to sort it out and get the drain nut in. It was a catastrophe. But writing about this was not the stuff that minor pop stars or celebrities did pre -internet. Suddenly this whole world of the ridiculous and the mundane and the perfectly wonderful became possible.

The book is called ‘A Dysfunctional Success’ because at the time that I wrote it I was looking at people I’d known who had become very successful, and people would say, ‘Don’t you feel bitter that your label mates have had all that success and you didn’t?’ But I’d say no, because I don’t think any of them seemed particularly happy. They didn’t seem overjoyed with their lives any of them. I didn’t wanna be them. I remember when Ian Dury got hugely famous and he met Paul McCartney. He asked him, how do you deal with when fans won’t leave you alone, and Paul said, ‘I run’. And Ian said to me, ‘I can’t run’, and he had tears in his eyes, you know? It was a really poignant moment. ‘I can’t run.’

So I didn’t envy them their success but there was a point in my life where I thought, I’ve actually quite nearly drunk myself to death and I’ve had a severe mental breakdown, I’ve spent time in a psychiatric hospital… All this kind of stuff has happened to me, and I came out of all that troubled in some way. I was challenged and damaged, but I thought I had found a point in my life where I could live with it. I could accept it. And I thought, that's a huge success you know? So that was my dysfunctional success. This one guy said to me repeatedly over the years, ‘I could be where you were if only I had the breaks’. Maybe you could you know, but I could say that to someone further up the chain, because there’s always someone bigger and tougher and harder than you, and there’s always someone cleverer, and there’s always someone more successful. It doesn’t matter how successful you’ve got, there will always be someone who has more of that than you.

I didn’t want to write a book to the glory of me, though, you know? I was kind of known enough, or had been known enough, to think that someone might find it interesting to read a book about me. But what I actually wanted to write about were two things that interested me. One was this whole thing of being middle class. My dad left work when he was 14 and my mother would have loved to have gone to university but started working in a bank when she was 16. Her parents had a newsagent shop and she wanted something better than that but I don’t think they knew what the world was ‘cause when they were in their formative years they were just being bombed. My dad left school at 14 and worked in the tool room which was a reserved occupation; he made parts for Spitfires, so he didn’t actually go to the war but I think that they were they were confused, they were freaked out, by going through all that. They’ve never had a chance to figure some things out. This is the legacy they passed on to us.

The other was school. I wasn’t alone in that. I went to the grammar school which was horrible really. I grew up thinking I was stupid because I wasn’t an academic. I’ve understood that since but that’s what I wanted to write about. The whole grammar school thing was a huge thing in my life. They just told you you were stupid all the time, and I don’t think I’m stupid, but I’m not academic. My mind is not disordered; I have quite a logical mind: it’s not disordered, but it’s disarranged and there’s a certain amount of damage from substance abuse and alcohol and everything. I’ve got these cousins that are all deeply on the spectrum. But it damaged me, it really did.

So I wanted to write about that. I wasn’t gonna write about every damn day of my life, and I had no interest in writing about being a pop star, the glory days of, gosh, how it felt that day I held a record that I’d made in my hand, you know? I just find those kind of books deadly dull. I went from school to art college to pop stardom to desperate nothingness. I think I was hopelessly immature. With a combination of my upbringing and alcoholism I never really kind of grew up as I should have done until late in life.

If you’re a musician and you have a band, that’s who you mainly see, you know and outside of going on tour, it’s a very lonely life. It’s very difficult to know where to belong. I never wanted to belong in the world of the limelight club. Like the music business, I didn’t like the people in it, but I wanted to belong somewhere, and I couldn’t in England when I stopped drinking because there was nowhere to go that wasn’t drink-based. People would say, ‘Oh, we went out the other night but we would we didn't invite you because we were going out drinking.’ I moved to France because I just wanted a different life, really. I don’t know what life I wanted, because the life was among people who lived duller lives than that you could ever imagine!

But it wasn’t therapeutic, writing the book. People think that all this stuff is some kind of catharsis. That’s a common mistake that people make: they think that every song that you write is autobiographical. But there’s a huge difference between therapy and something that other people can relate to. I might not be successful at it, but I always have in mind that it's got to be relatable in some way, and that takes it out of the therapeutic.

When I was re-editing the book, I just thought, ‘God, I don’t want people to read this!’ But then I thought, I couldn’t actually write anything about myself that had the truth in it if you had it in my mind that anyone was going to read it. So I just put that out of my mind. Like with making records, there was a time when Stiff Records would say, ‘We want you to sound like Brinsley Schwartz’, and then the producer would say, ‘We want you to sound like Plastic Bertrand’, and I’m like, ‘OK, I’m confused!’ So I eventually learned that the only thing you need to be is like yourself in some way. And that's a very difficult path to follow. It can be scary. But you can’t do it to please other people.

I’ve always had a thing that you can either spin a story or you can tell the truth, and I don’t think there’s much middle ground. You’ve got to somehow have the truth in it. When I was in The Len Bright Combo it was, ‘No one wants to hear this! Get some more jolly songs!’ And I was, ‘Yeah, but I want to express myself!’ You’ve got to get some balance somehow; it has to be the truth but it also has to be something that people can relate to. It’s not just like having a breakdown in front of people. I will put myself into what I do as best as I can, but I don’t wanna have a breakdown in front of people.

I had been in hospital. I’d been through a fairly awful time. I mean, I decided at one point I was never going to play music again, because all I had succeeded in doing was in bringing deep unhappiness, just proliferating my own unhappiness and bringing misery to people. In the mental hospital, I’m surrounded by people who were having crises and people shouting at themselves and all that and in the middle of all this, I sit there reading a book.

‘No-one knew who the fuck I was, you know, but then suddenly there was a doctor came over from the other part, the real looney part of the hospital, and he said, ‘Hi, I just wanted you know I’m a real fan of your stuff, and I just wanted to let you know you really helped shape my existence.’

I got in before they sectioned me, you know; technically, I was voluntary. I mean, I was at the point where I was probably dangerous too - I was screaming at people in the street for standing too close to me and I was in a terrible state. I couldn’t stand it any more, so I went to a casualty department at 7:00 in the morning and suddenly there were security men and a social worker, and I said, ‘I’d like to go somewhere. They were gonna section me, but I got in before they did.’

Being in the hospital was the best holiday I’d ever had and I kind of slowly got to the point where I could function again. Eventually, I was an outpatient, and I got a flat and I got to a point where I actually looked forward to the next day. I think within a year I’d started playing and suddenly I was playing a lot. I was gonna sell this guitar I had, and I was just fixing it all up to sell, and I got a phone call from this guy who said, ‘I want you to come and do a gig for me. I want you to come and play solo.’ I said no again and again, but then he told me what he was gonna pay me and it was exactly what I was gonna get for selling the guitar. So instead of selling the guitar, I used it to do the gig! Suddenly I was playing all these gigs in Europe where they actually pay money, they put you in hotels and they give you dinner and it’s really fantastic.

When I lived in France I lived alone in the middle of nowhere. I had limited communication, because I had to learn to speak French. It wasn’t like that ‘A Year In Provence’ kind of stuff, it was the France you’d expect French people to live in. You might think that’s literally the worst place to go if you’re depressed ‘cause you’re trapped in your own head with no distractions. You would think that you would be much more depressed in those circumstances, but no, I had to make an effort to communicate. I had a Penguin phrase book, I had a suitcase of clothes, I had two guitars and a 15-Watt amplifier, and there I am like some clapped out vehicle. Before I could go into a shop to buy some food, I’d have to rehearse what to say. It was terrible. I had to survive. I learned to take time to eat because French people always did. I went out for long walks. I started to sort of divide my time in the day. I’d get up in the morning, have some breakfast, and then I’d go out for a walk. Then I’d go to a cafe and have some coffee, watch the world go by and think about what I had to do. Then I’d come back and start writing songs, working on some ideas.

I learned a lot from living in different places. I think there was a time that I was definitely running away from stuff and desperately wondering where I came from. There’s this idea that you find this place, and this is your spiritual home. I feel very comfortable now being in Norfolk for some reason. It makes me happy to be here, and when I go back to where I came from, the South Coast, it doesn’t it doesn’t speak to me. I thought that I related to the landscape, but I found out that I don’t. It’s just that it takes years to figure this out unless you - maybe other people have it all sussed out, but it’s taken me all my life.

Am I happy now? I think so, yeah. I mean, I’m not happy with the way the world is. If you look further than the end of the street, the prognosis is fucking bleak. I think, have we learned nothing? The very people who were the Holocaust’s victims are visiting that on some other people. I feel deeply depressed about all this. I think we all do, or a lot of us do. I don’t think anyone thinks it’s funny. Like, where we’re just moving from, there was a big pickup truck that would drive around belching black smoke with a fucking great big flag that said, ‘God. Guns. Trump’ flying off the back of it. I mean, what the fuck!?

People have laughed at me, but I’ve been saying for a few years now that I think America is heading towards a kind of a civil war. I don’t think America will remain as one federal country. It will become some different countries: a West Coast country and East Coast country, and a couple of countries in the middle of it. They said that Trump would never get back in, but I was in America while he was campaigning, and I could see it all happening.

It's a sad state of affairs really, what we've done to the world. I have thought a lot about religion in western civilization, and it's not really about a man in the sky or a mythical place where you go when you die, or some poor sod being nailed to a piece of wood. The real purpose was it gave people a social and moral structure. There are always people who want things to remain the same, like there are people who are nostalgists or whatever because from the industrial revolution on, it changed so quickly but the moral structure never kept pace. In a way we’ve got rid of all that. I think it’s left a lot of people in freefall. I’m not proposing bringing it back, but it’s left a void in some way. So there are people that want to bring it back. It’s alarming, particularly in America, there are people trying to change it back to the Old Testament - the anti-abortion laws, eye for an eye kind. But I think the only purpose of history and of the past is actually to help us to do better in the future. Some people deify the past, and I think that’s a mistake. It’s there to teach you. You can’t go back and change it, but you can learn from. And if there's a lesson that you need to learn in your life, if you don't learn it, it'll keep coming back time and time again until you do. And then you can move on.

I was 70 at the weekend. You start to look at your life and wonder, ‘How did I get to here?’ And it’s exhausting if you start looking at that. ‘I was there, and then I did that, and then I was with that person, and that was a nightmare, and then I did that, and I didn’t want to do that but somehow I started to, but I decided not to… and you go down this kind of rabbit hole, because it’s all so complicated. It’s exhausting being older - you’ve got so much life to look behind at. Because life is a constant process of self-development. I mean, I’m a complete catastrophe in other ways. I’ve never had a real job, and never had any kind of structure in my life. No Sundays off to reflect on. I can’t go to bed at night. I’m also obsessive. I’ve got this list of things to do… but, am I at peace with myself now? Yes, I think so. As much as you can be. As long as I don’t catch sight of my reflection!

Band Links:-

https://www.facebook.com/wrecklesseric

http://wrecklesseric.com/

https://www.instagram.com/thewreckless

https://twitter.com/thewreckeric

Play in YouTube:-

Picture Gallery:-