published: 8 /

6 /

2025

Johnnie Johnstone speaks to John Clarkson about his first book, ‘Through the Crack in the Wall: The Secret History of Josef K’, which is Pennyblackmusic’s Book of the Year for 2024.

Article

Named after the persecuted protagonist in Frank Kafka’s unfinished 1925 novel, ‘The Trial’, Josef K was a part of the same creative and fertile period of Scottish rock and pop of the late 70’s and early 80’s that also saw come to the fore such acts as the early Simple Minds, Orange Juice, Aztec Camera, The Fire Engines and The Associates.

With their brittle guitars and Paul Haig’s angsty, guilt-loaded lyrics, hey are now seen to be an influence on acts as diverse as Franz Ferdinand, Interpol, Wire and Bloc Party.

Signed to the legendary Postcard label, run by Alan Horne, they were briefly touted with label mates Orange Juice as being the ‘Sound of Young Scotland’ and championed by influential critics such as Dave McCulloch in ‘Sounds’ and Paul Morley in ‘NME’.

They, however, ‘had little success in their lifetime. A debut album, ‘Sorry for Laughing’, was recorded but scrapped by the band, who dubbed it ‘too clean’ at the test pressing stage in early 1981. Its successor, ‘The Only Fun in Town’, which was more frantic and trebly in sound, followed in July of that year, but Josef K, however, broke up mysteriously on the night of a final gig at The Mayfair in Glasgow just days after its release

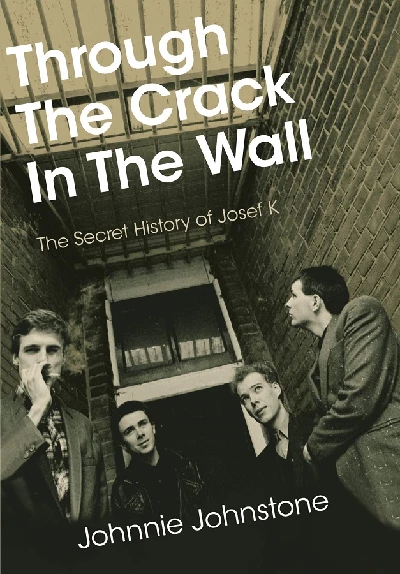

There has been much speculation about the band, who were together barely three years and have never reformed, in the four decades since their demise. Johnnie Johnstone’s new book and the first biography of the band, ‘Through the Crack in the Wall: The Secret History of Josef K’, which is Pennyblackmusic’s Book of the Year for 2024, does much to unravel the truths about the band, and how four ordinary young men – Paul Haig (vocals), Malcolm Ross (guitar), Davy Weddell (bass) and Ronnie Torrance (drums) created something extraordinary.

We spoke to Johnnie Johnstone about ‘Through the Crack in the Wall’.

PB: You first came across Josef K in 1987. What was the initial appeal to you of them then?

JOHNNIE JOHNSTONE: I was nineteen at the time, so they had already been split up for seven years and I was very late to the show. I was not usually the first person to discover new bands. It was normally passed on to me by other people who had got there first (Laughs), but I noticed that this band Josef K had a compilation, ‘Young and Stupid’, out and I asked for it for my Christmas from my mum.

I wasn’t sure what to expect from it, but when I got it on my turntable I was absolutely thrilled. It was a little like – a similar experience – hearing The Velvet Underground for the first time. A lot of the shambling and C86 bands were around at that time. but they left me a wee bit cold, and I found Josef K a bit more vibrant and energetic. I also really liked the look of the band. I thought they looked really good.

PB: Why do they still appeal to you now?

JJ: I didn’t really listen to pop music for a long time. I held back from it, and I am at an age now – I am in my mid 50s– in which you recapture your youth. and a lot of the bands that were so important to you.

The music of Josef K stands the test of time really well. It still sounds as exciting today as ir did back then in the late 1970s. and I don’t think that you can say that about too many bands. A lot of the music that was made back then sounds really dated now, and I don’t find that with Josef K. It still sounds quite modernist.

PB: Is part of the attraction because they were so short-lived?

JJ: That is the mystery of it, isn’t i6t? I originally started writing this imaginary story about the band playing iive in the late 1990s and doing a tour to promote their twelfth album or something like that, and I wondered what that would have brought if they had the same level of fame and success as The Cure and Simple Minds, and what it might have done for their reputation.

One of the great things about Josef K is that they disbanded at the absolute heights of their power, when they were young men, and in photos of them they are sort of immortalised. They are twenty years old, They will always be twenty years old. With the book coming out, I was hoping, against all reason really, that the guys might be willing to do an acoustic set at the book launch or something like that, but they have been pretty adamant about that, that they won’t be, They have been pretty firm about that (Laughs), because they don’t want to be remembered as guys in their sixties. They want to be remembered as they were. It takes guts to do that because it would have been good for the bank balance if they had reformed. They never really fell out with each other. They get on fine, but if they played together in their eyes the legacy of Josef K would be tarnished.

PB: You point out at the start of the book That Josef K were not and are not especially well known. How easy or difficult was it for you to find a book deal when they were such a cult act?

JJ: There were a few things that made me think that it might work. The original idea came from me going to the premiere of ‘Big Gold Dream’ (a documentary directed by Grant McPhee about the late 1970’s/early 1980’s post-punk and indie scene in Edinburgh and its bands - Ed) at the Edinburgh Film Festival in 2015. There was a big crowd in that night, and I suppose it raised the profile of art bands and the Edinburgh scene, and Josef K featured quite strongly in that. Out of all those bands in it, they were my favourite. Their profile was out there a bit because of that. Then I learned that Grant, who made it, was working on the ‘Hungry Beat’ book about Scottish post-punk with Douglas McIntyre, and I thought, “Well, I think Josef K deserve a book of their own.” I know it is a niche market for the book, but I was quite surprised when I did some pre-publicity for the book that I met with quite a positive response.

I did pitch it to a few publishers. I didn’t really know how to go about it, and rather foolishly I sent it out to three publishers at the same time. I think that you are just supposed to send it out to the first publisher and to see what happens in order that you are not wasting people’s time, but Jawbone Press was one of them and they were immediately interested in the idea. I was very fortunate that someone was prepared to give me a contract.

PB; Josek K broke up when its members were 21 at the most. Do you think that it has been hard for the four members of Josef K that they are always going to be known best for something that finished when they were barely away from their teens?

JJ: Yes, but just to a small degree. Paul still lived at home with his mum and dad, and Malcolm and Davy had only recently left home and were flat-sharing. They were very young guys, but they have all gone on to be successful in other ways afterwards.

Ronnie and Davy both went on to have families, and had both left the music business by 1984. They both live abroad, Ronnie in Portugal and Davy in Spain. Ronnie ran his own property investment country and Davy works in television.

As for Paul, he has pretty much been making music ever since, Sometimes there will be a gap for four or five years. There were a couple of records in the mid-80s that were fairly successful, and ever since he has been making music that he likes, and, while none pf these have sold in high volumes, I admire his integrity for continuing to make music on his own terms. Malcolm went on to play and have greater success with Orange Juice and then Aztec Camera. In his solo career he has also made a few records of his own.

PB: Josef k had a reputation for being quite elusive. Its members have not always been particularly forthcoming when talking to journalists previously, but with your book you got a massive amount from them. How did you achieve that?

JJ: Certainly, it varied between them. As Davy and Ronnie now both live abroad, it was harder. It was all done by phone, and there were quite a lot of those.

With Malcolm and Paul, I was able to visit and meet up with them. Malcolm and Paul were very different. Malcolm right from the word go was quite keen on the idea of the book and was supportive and encouraging of it and very open. That is not say that Paul wasn’t. Paul is just a quieter, more private person. He likes to stay out of the spotlight, which is why he has not taken part in any of the book launch events. I think that he found Josef K such a challenging time that he finds it difficult to talk about it, but having said that when I went to see him he was always open and honest. He wasn’t difficult or awkward. Malcolm, I think, is better at putting things in perspective and is quite proud of what Josef K achieved. Like Paul he wants to move on, but he finds it easier to talk about that era, although for him it must be as painful as for Paul.

PB: Postcard boss Alan Horne comes across as being absolutely obnoxious. Did you intend to portray him quite so blackly?

J: When I started on the book, I thought that it would probably be a good idea to call Alan Horne, but then before I got around to it, I thought, “What’s the likelihood of him talking?” I got the impression that Alan didn’t want to talk, so I didn’t ask him, which was presumptuous of me. I thought that he would probably reject the idea or might try to undermine the credibility of the book.

The other thing is that Simon Goddard’s book ‘Simply Thrilled’ about Postcard was published a few years ago. It is a great book. I love it. It is a great read, but it has Alan Horne’s fingerprints all over it. I don’t know if this is true or not but you get the sense that it is an authorised study of Postcard, that Alan Horne is pulling the strings.

I didn’t want my book to lack integrity, or to be persuaded by Horne. I would hate that. I felt that it might be fair to hear what he felt about it, but on balance there was a danger of publishing something that came from his rather than the other guys’ and my own perspective. I thought that it was maybe better to let the band speak.

PB: Allan Campbell, their original manager, was quite a stabilising influence on Josef K, but he quit and left them with Horne in charge. He was trying to hold down a job teaching and he was organising gigs and doing club nights and running a record label as well. Do you think that he quit as manager because he had too much else going on?

JJ: I think that it was down to a combination of factors. Certainly from Allan Campbell’s perspective he had a lot going on. He couldn’t really juggle it all together. He was running nightclubs and he was teaching during the day, He had a busy, hectic lifestyle. There wasn’t much money coming in and managers need paying, and Allan Campbell was pragmatic enough to real8se that it wasn’t going to work, having to be paid by Josef K when there wasn’t any money.

Alan Horne he just had a way of making a starement, of getting the music press on board and of getting a lot of publicity, and it was inevitable that he was going to take over. The band are maybe not appreciative enough of him and his input as they should be, but at the same time he was a catalyst for their demise. They are still now split down the middle about their relationship with him, and I think he caused them to question themselves and their abilities. He wasn’t supportive of them. I don’t think that he really liked them to be honest at a musical level. They would have been in safer hands with Allan Campbell.

PB: Why do you think ‘Sorry for Laughing’ was shelved? You imply that Josef K lost their nerve.

JJ: On a personal level I prefer ‘Sorry for Laughing’ as a record. A lot of the people that I have spoken to, however, prefer ‘The Only Fun in Town’ . It was all about timing. The band wanted a reflection of their live sound. They were gaining a reputation as being a really exciting live band, so when they went into the studio they sounded a little bit squeaky clean. It was not as exciting as they wanted it to be. They were developing fast, and everything new they recorded was a bit more shiny and to go back a step and to releasw something with the sound they had in 1979 was no longer appealing, but it was bad news for their careers. That is for sure. You can argue all day which is a better album but it was a real mistake not to get that album out.

PB: Josef K split in the summer of 1981, How much of that do you think was down to them growing apart as individuals?

JJ: I think that was probably the main reason. It happens, doesn’t it? You are a close band of friends, but your eyes are opened when you are in the spotlight. So much is happening around you. They really cared for each other, but they had been out on the road a lot and it is tough when you don’t have much money coming in, All these tensions start coming in, and then Paul said that he would rather not play live.

Paul and Malcolm’s upbringings were very different from each other. You look at Paul’s upbringing. It was fairly stable domestically. Malcolm was a lot more challenged in his childhood, and there was perhaps more openness to experience and trying things out and just getting by when there were hard times. Touring suited Malcolm more and he found it an exciting experience. I think that became a sticking point between the two of them and they were not rehearsing or talking much by the end. They never fell out, but just grew apart,

PB: Thank you.

Play in YouTube:-

Picture Gallery:-